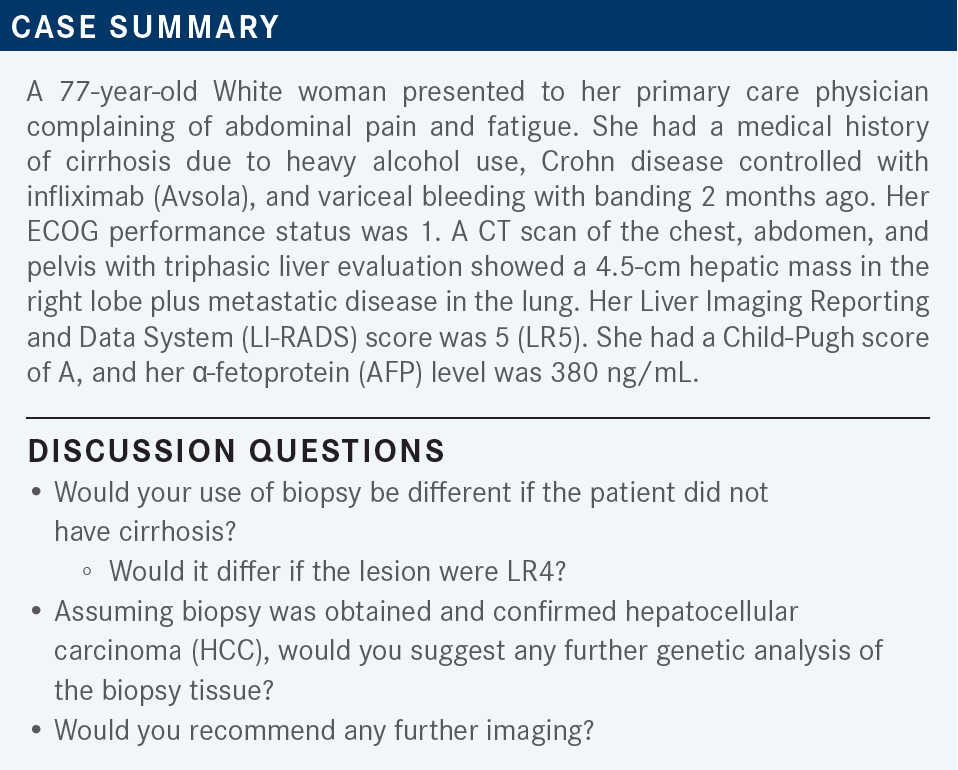

Roundtable Discussion: Abou-Alfa Evaluates Choice of Therapy for HCC Based on Patient Factors

During a Targeted Oncology case-based roundtable event, Ghassan K. Abou-Alfa, MD, MBA, discussed the case of a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma whose comorbidities impacted the choice of treatment.

Ghassan K. Abou-Alfa, MD, MBA (Moderator)

Medical Oncologist

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

New York, NY

SIDDIQUI: If [the LI-RADS score was] 4, I [would] probably do a biopsy. The other [possible] benefit of biopsy is next-generation sequencing [NGS], but I’m not sure if NGS is very helpful in HCC.

ABOU-ALFA: That is a great point that you bring up. [There are] a few points [to consider] about the biopsy. [Concerning] LI-RADS…I spoke with the radiologist who wrote the final LI-RADS radiologic assessments.

I got [what is] probably the best answer from him. He [said that] when [medical oncologists] talk to each other, one can say, “I have a patient with stage IV disease,” and the other one will understand that the disease is not resectable, it’s not curable, [and so on]. Interestingly, the LI-RADS [score works similarly] for radiologists. They can say, “I have a patient with an LR5 lesion,” [and] their mindset is that this is probably HCC. I asked the very direct question [of whether they would] be ready to say that a patient had HCC [on the basis of] the radiological assessment by itself. And the answer was no, because sometimes those can very much [indicate] other things [such as] cholangiocarcinoma.

A patient can have combined cholangiocarcinoma and HCC, which can happen in up to 15% of patients. And interestingly, some other things [besides HCC] can [produce] high AFP. So I think we’re obligated to get a diagnosis to know what’s going on [with] the patient. Almost all the clinical trials that were done in HCC were biopsy driven; nothing was done radiologically.

[Point] No. 2 is that with regard to genetic testing, it’s not like we have too many options to offer the patients. But if we don’t do the testing and learn from it, we’ll never be able to tell what the story is. Can we see certain genetic alterations that can be applicable in HCC? Yes, we can. We have seen [alterations], for example, [in] FGFR2, FGFR4, FGF19, and IHD1. So it’s not only in cholangiocarcinoma; it can happen in HCC as well. I strongly recommend to you to do a biopsy at all times.

[At] Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, when a patient comes in, we get a biopsy [and] we send it to a pathologist to be reviewed. At the same time, we will do genetic testing, exactly as we just discussed. On top of that, believe it or not, we take a sliver of that tissue…and we’ll send it immediately [and] embed it in mice for a patient-derived xenograft mouse model.

We’ll learn a lot from the patient’s disease, and we can offer the patient better therapy. And that’s why, with all those options in front of us, it will be [important] that we develop a better understanding of the tumor. My recommendation is, by all means [do] the biopsy. I think it will be the right thing for patients, and let’s not depend, as medical oncologists, on the LI-RADS testing, which is not enough for that purpose.

ABOU-ALFA: [The patient] had Crohn disease, and she [also] bled from varices and she had banding 2 months ago. My question is, with varices, what’s your comfort zone? [At what point do] you think you can give bevacizumab [Avastin]? [Do you not wait] at all, wait 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, or 1 year?

SIDDIQUI: [I think it] should be a couple of months.

ABOU-ALFA: In other words, 2 months is enough? I have to admit, I’d be worried. The comfort zone, [based] on the IMbrave150 study [NCT03434379], is 6 months.1 So [to give] bevacizumab within 2 months after variceal [banding is] not a good idea. If you remember, [when] bevacizumab [was investigated] as a single-agent therapy for HCC, [a patient died from a fatal variceal bleed].2 I urge you not to fiddle in that arena, because patients can get hurt from potential bleeding.

Any comment in regard to the Crohn disease? How much does it worry you with regard to atezolizumab [Tecentriq] and bevacizumab?

BENDALY: I would be worried, especially if [the patient were] on immunosuppressive treatment. I don’t know how it would interfere with the activity of immunotherapy.

ABOU-ALFA: Yes. That’s very true. I personally would agree with you. But on the other hand, you might very well [choose to] send the patient to the gastroenterologist and let them assess [the situation]. If the Crohn disease has been rather stable, [with] no events, [you might choose] close monitoring. I [could] understand that. So the varices would [definitely rule out] the bevacizumab, and the Crohn disease [might rule out] the atezolizumab. [The decision about using atezolizumab could] probably [go] either way. I would be rather cautious.

This is the point: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab, as great as [this combination] is, is not a choice for everybody. And probably in this specific patient, with relative concern about the Crohn disease but more critical concern about the varices, I would urge you not to give atezolizumab plus bevacizumab here. If anything, I [would choose] to give lenvatinib [Lenvima]. That is probably the right option for this patient.

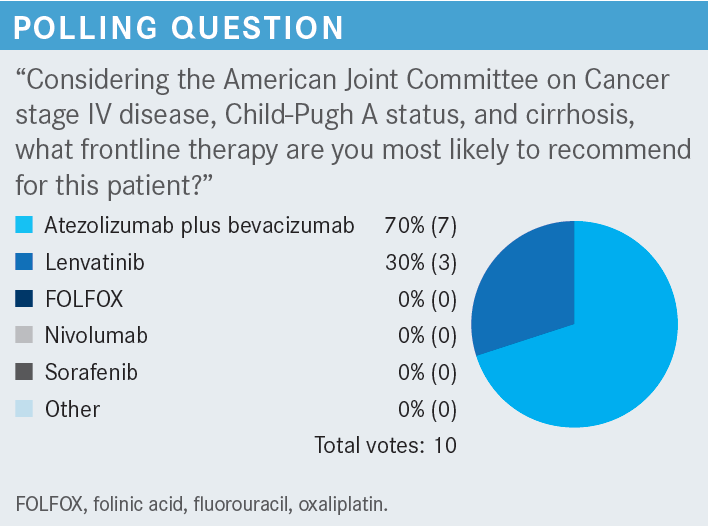

SINGH: I think, realistically, all of them [are important], but my top 4 would be etiology of the cirrhosis, comorbidities, performance status, and Child-Pugh status.

ABOU-ALFA: I agree with what you said, and I like very much what you said in the beginning, which is [that] truly, they all apply. But I’m curious about 1 thing: you mentioned the etiology. [Do] you choose 1 therapy [over another on the basis of etiology] (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or nonviral [hepatitis])?

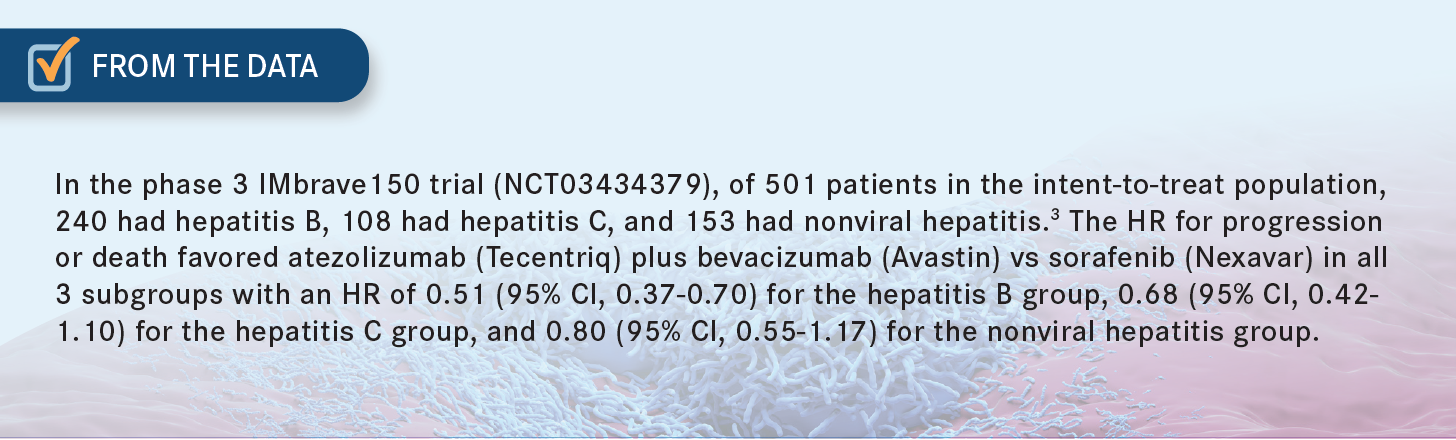

SINGH: I think it’s more of a curiosity, because I know that in the study of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab, they did have a significant portion of patients, who were hepatitis B positive. Those patients had a more positive response.3 So if you know that is the etiology of their cirrhosis, [and] they otherwise don’t have any variceal bleeding, [and] you think they can tolerate bevacizumab, [there’s] no reason why [they couldn’t] have immunotherapy. [This line of thinking] guides me toward a regimen of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in those patients with hepatitis B.

ABOU-ALFA: You’re absolutely right. About 40% to 50% of patients in the IMbrave150 [study] had hepatitis B.1 And we know very well that patients with hepatitis B can fare better on immunotherapy, independently of what immunotherapy you give. [Those faring next best were] the patients with hepatitis C, followed by those with nonviral hepatitis [From the Data3]. But [it is] very important [to note that this] does not mean that the patient with hepatitis C and the patient with nonviral hepatitis will not benefit. Everybody will benefit but, as you said, [there may be] a bit more [benefit] for the patients with hepatitis B than for the others. Yes, out of curiosity, I too like [to know the etiology], but I would not make the [therapeutic] decision based on the [etiology]. [Etiology] might play a role in the future, though we’re not there yet, but I like your analysis.

ABOU-ALFA: We probably all see [cases like this one]. Does this reflect the experience that you have had with lenvatinib, or have you had a different experience?

TAJUDDIN: I don’t have experience with lenvatinib in this situation, but I have used it in metastatic thyroid and uterine cancer. [My patient] with metastatic thyroid cancer is doing quite well with the reduced dose, and he’s responding. The [patient] with uterine [disease] is not doing so well; [this is] because of poor tolerance, especially [gastrointestinal] toxicities. [It reached] the point that she said, “I absolutely don’t want to take this drug because it’s making me feel awful.” So these are 2 different experiences that I had.

ABOU-ALFA: You hit it right on; a reasonable number of patients will end up needing dose reduction to 8 mg. But I hope after [our] discussion, you’ll join us with regard to giving lenvatinib to patients, because I think it is easily tolerated. That’s a big plus for the drug, no question about it.

KU: I haven’t used lenvatinib in liver cancer, but I’m using it in other cancers like kidney cancer. I run into AEs like hypertension [and] diarrhea. I have used sorafenib in liver cancer, and I dealt with a lot of appetite and weight loss problems.

ABOU-ALFA: Yes, I think you’re right on all of that. And by the way, don’t expect the AEs to be different depending on the disease. [The things you mentioned] are the [AEs] that we expect in regard to lenvatinib. You will [also] probably see quite a bit of hand/foot syndrome [with] sorafenib.4 Patients don’t like sorafenib; it can cause [a lot] of AEs and can be a problem.

KOKO: I have a patient currently on lenvatinib for endometrial carcinoma, I think. Hypertension has been a problem, but she also [developed] congestive heart failure, which she never had until she was placed on lenvatinib.

I’m concerned that [the lenvatinib is the cause]. I had to reduce her dose. Initially, the dose was held for a while, and then [I reduced it] to 8 mg, which she’s been tolerating well. But she was hospitalized multiple times with congestive heart failure when she was on a higher dose. Since [I reduced] the dose, she hasn’t had any further episodes.

ABOU-ALFA: Thanks so much for bringing this up; this is quite intriguing, because it’s a very uncommon AE that can occur. We have seen this with tyrosine kinase inhibitors [TKIs] across the board, and it can happen with lenvatinib, like in many others. But again, it’s not like we see it all the time. This is a very rare AE, but it does happen.

NABRINSKY: I can only reiterate what my colleagues said. And when it comes to appetite loss or taste changes, [these are] quite common, and we never know whether [they are] attributable to the disease itself or to the drug. That’s a judgment call.

ABOU-ALFA: I think you’re absolutely right. Those AEs can be [attributable to] both [the disease and the drug]. [And because they] can be [caused by] the drug, a reduction of dose will probably help. If you reduce the dose to 8 mg, it [can improve] the appetite. By all means, it’s something you can practice.

TAJUDDIN: Dose reduction is very common with lenvatinib, regardless of which kind of tumor you are treating. So, would it be fair to start at the lower dose or would you still want to [start with] the [original] dose intensity?

ABOU-ALFA: Let me give you a little background on this. Interestingly, the whole story about starting on a low dose started with sorafenib. The sponsor of sorafenib wanted to do it that way because they were very concerned about the hand/foot syndrome. But we’re all taught to give [chemotherapy at the] full dose and this applies also to TKIs. No, I would not start on a lower dose; I would start on 12 mg.

You’ll be surprised [to see] that patients can tolerate it, and they can do very well with it. Of course, however, I’ll have a very active role in trying to reduce the dose if I have to. I urge you all [not to] give the lenvatinib and tell the patient, “See me in a month.” You’ll probably have to see the patient in a week’s time, because AEs will happen very quickly. You want to be sure [you are monitoring the situation and watching] for any symptoms that can occur, [including] congestive heart failure, as Dr Koko [mentioned]. Close monitoring is needed, especially in the beginning.

BARAI: In any of these treatments, does it make any difference if the patient has elevated AFP, [in comparison with the] small percentage of patients with HCC who don’t have elevated AFP? Is there a difference in their responses?

ABOU-ALFA: AFP is not a prognostic marker for HCC. [Elevation of AFP] can happen for many reasons. Any inflammation of the liver, no matter [the cause], can [result in elevated] AFP, [as can] gastric cancer. It appears that [elevated] AFP might imply liver dysfunction, but it does not have any prognosticative [power]. I will check it, but I usually don’t check on a regular basis. I check regularly only on CAT scan times, and I [only] use [AFP level] as a third [consideration], after the [results of the] physical exam and the CAT scan, before I make a decision. But [you make] a great point.

References

1. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894-1905. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

2. Siegel AB, Cohen EI, Ocean A, et al. Phase II trial evaluating the clinical and biologic effects of bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):2992-2998. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9947

3. Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):862-873. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030

4. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163-1173. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1