Roundtable Discussion: Education and Treatment of Patients With Myelofibrosis

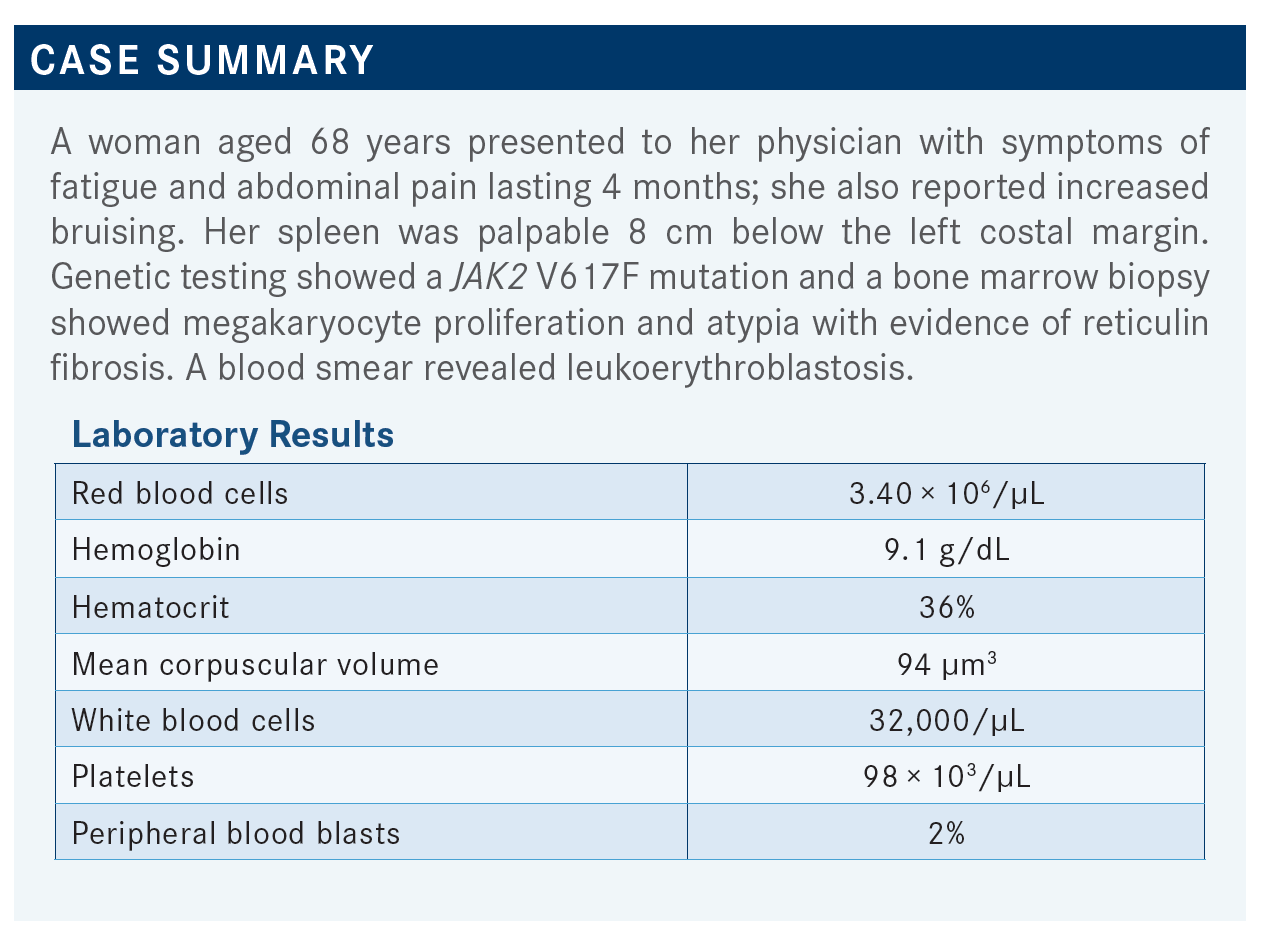

During a Targeted Oncology case-based roundtable event, Angela G. Fleischman, MD, PhD, discussed how to approach treatment of a 68-year-old patients with myelofibrosis.

Angela G. Fleischman, MD, PhD (moderator)

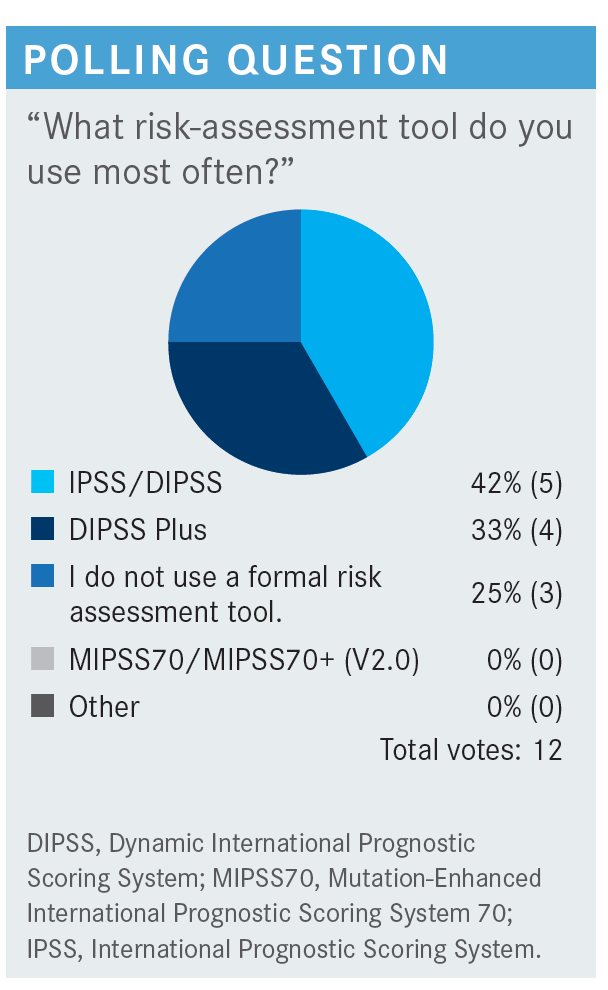

FLEISCHMAN: What do you think of the current risk-assessment tools?

DEKKER: Risk-assessment tools are more relevant for patients who [are younger], candidates for trials, transplant, etc. If you have an 80-year-old, whether they are low risk or very high risk, it will be dependent on what the patient wants, how far the patient is willing for you to go, and the other comorbidities.

FLEISCHMAN: I agree that the scoring tools are most helpful in a younger person for whom the transplant question is a reality. It seems like every year at ASH [American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition], there are more of these prognostic scoring tools. We have a lot of scoring tools here.

CHAUDHARY: They also help you have a discussion with the patient about what we expect and what their prognosis looks like. I always calculate the score.

FLEISCHMAN: You are saying [that in the context of providing] help with patient education and for the patient to understand. I have had patients come in who found these scoring tools online, and they bring a printout with their scores. That is a rare circumstance I have encountered, but patients do find these things online and score themselves. Has anybody else had a patient come in scoring themselves?

SWEET: I have not, but…now that there is a proliferation of patient access to the medical records…they can look at their blood counts. They can probably even look at their pathology reports. You are right; this is likely to increase, but the patients are going to present us with all the data and ask us to elaborate.

DEKKER: I would somewhat agree. Probably 50% of phone calls or messages that I get from patients are, “I see my results in my chart; I do not know what it means. I am very anxious.” A few will do the research and go further, but most of the time they try to make an appointment between appointments.

CHANDURI: My experience is [initially] the patients may come 1 or 2 times [on their own]. The third time, usually, they come with their kids. When their son or daughter hears about myelofibrosis or some kind of blood disorder, that is when they will google it and they will bring all these things. Then they will ask, “Doctor, why are you not treating? Is it this? Is it that?” In the past year or so, I am finding this more. That is why it is better to give them all these tools up front.

FLEISCHMAN: Do you think increased patient education or access to information is a good thing?

CHANDURI: I think it is confusing for both. But it is happening, so we need to have a tool to communicate with these patients [explaining] if we are not going to treat them, why we are not treating.

Or if we are treating them, why are we treating? Because a lot of these medications are advertised on the television and then they will say, “Doctor, I have polycythemia vera [PV]; why are you not giving me this medication or that medication?” We need some tool because patients are coming in with this information.

FLEISCHMAN: I agree. I think in the United States, [individuals] have the mentality: “If I have a disease and there is a treatment for it, I deserve this treatment for it.” But [it is important] to communicate with the patient exactly what a specific treatment can and cannot do—just because you have myelofibrosis does not mean you need a JAK [Janus kinase] inhibitor. Just because they are available does not mean that it is appropriate for the person.

DEKKER: But that is why all those agents are advertised online. When my son was 11, he came to me and told me about Neulasta [pegfilgrastim], because Neulasta was advertised in a YouTube video.

SWEET: There is a dichotomy of patients. There is still a large subset of patients in my practice who do not have the ability to get into the medical record or understand it.

The patients who do a deep dive often focus on the wrong things….I do attempt to provide some education. Sometimes I find the brochures from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society helpful to give the patient, once myelofibrosis is established, to give them a deep dive into their disease. I find the sections or subchapters in UpToDate that are relevant to the specific issue, like treatment of myelofibrosis. Something a little more focused, even though it is sophisticated reading, can be helpful in putting the patient more on a level of my choosing and not have them go all over the internet.

FLEISCHMAN: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] guidelines also have a patient version, which, for the myeloproliferative neoplasms [MPNs], is pretty good.1 It is mostly bullet points and pictures, and I think it covers things in good depth. Sometimes I look through the patient verison when I want an answer to a question like “What do I do in this situation?” quickly. I am sure [individuals] can get that for free online, too. That is also a good source.

CHAUDHARY: I think providing background takes away anxiety from the patients….Giving them the tools such as “this is your score, this is your risk category, this is what we are going to do,” like a road map, helps take away that anxiety and future visits are easier.

SWEET: [Yes,] especially in diseases that do not necessarily have a clean bidimensional record of treatment response.

TALREJA: I agree, because some diseases have a clean-cut “do this, this, this, and this.” But in myelofibrosis, there [is no] clean-cut “do this and do that.” Some patients you watch forever. Some you give epoetin alfa [Procrit]. Sometimes you give ruxolitinib [Jakafi]. I do not think we should tell them so much about the disease; then they take that home and they come back and ask you, “Now, why aren’t you doing this?” It is so confusing for them.

FLEISCHMAN: Every patient is unique. For one person, a little information might be good for them, and they will stop asking you questions. Another person will ask more questions. The information is out there; if they want it, they can get it.

Now, say you have a [patient with] myelofibrosis; how often would you go back and peruse the NCCN guidelines to help with decision-making?1 How many of you have to look at the NCCN guidelines for MPNs?

DEKKER: Once, for sure.

SASTE: Once or twice a year. That is about it.

CHANDURI: Whenever there are new patients.

FLEISCHMAN: I am not sure how many versions there are, because it’s relatively recent that they have had NCCN guidelines. [The NCCN guidelines have been updated because of] pacritinib’s [Vonjo] recent FDA approval.2

For one patient with PV, when there was some discrepancy in terms of appropriate treatment, I pulled up the NCCN guidelines for PV in front of the patient and said, “This is where you are, and here is the [next step].” I think I have done that a few times.

CHAUDHARY: I had a patient who asked me to [check] JAK allelic burden every time she saw me.

FLEISCHMAN: Do any of you check JAK2 allele burden?

TALREJA: I do that to see whether it is going up, and getting better, and what is really happening to the disease—just out of curiosity, and it is interesting to see. Sometimes it is helpful and sometimes not at all.

I used to see hydroxyurea [Hydrea] reducing the JAK2 burden. But sometimes it did not, so I said, “All right, what am I going to do?”

FLEISCHMAN: How about other [individuals]? Do you check a JAK2 allelic burden at diagnosis, and then do you follow it?

TALREJA: Yes, I do follow it.

SASTE: I do not.

DEKKER: I have not.

CHAUDHARY: For those who ask for it, yes. Otherwise, I do not know.

FLEISCHMAN: I follow it if a patient is going on interferon. Many [patients] who go on interferon are very proactive, and they are doing it because they are hopeful that it is going to bring down their JAK2 allele burden. In that case I say, “Let’s see where you are before you start the interferon and then let’s spot-check you after you have been on interferon for a while,” because that is their intention. They want to go on interferon for that purpose.

CHAUDHARY: That is exactly right. Most of my patients who ask for it are on interferon.

FLEISCHMAN: In your practice, what is the trigger to initiate therapy for a patient with myelofibrosis? This question is focusing on JAK inhibitors.

SASTE: Symptomatic splenomegaly [is my primary trigger].

TALREJA: Abdominal pain, satiety, losing weight, discomfort, or the patient is getting progressively anemic and needs a change in treatment.

FLEISCHMAN: What about for that patient who may not necessarily have splenomegaly, [but] they were just picked up because they had some mild anemia; they would not have known it if somebody did not tell them that they were anemic, and they sort of stumbled on the diagnosis of myelofibrosis? Would you be enthusiastic about a JAK inhibitor in that person, or just let them be?

TALREJA: This patient was pretty anemic, hemoglobin was only 9.1 g/dL; if you put her on a JAK2 inhibitor, she is going to get more anemic.

FLEISCHMAN: The question is: Do they have other reasons to be on a JAK inhibitor, like [large spleen volume or being symptomatic]? But if they do not have those 2 issues, then [how would you treat]?

TALREJA: She was losing weight, and she had abdominal discomfort and things like that, but anemia was bad.

SWEET: The question, then: Is there a relevant role to treat in a presymptomatic phase? Because, as you alluded, the anemia is likely to worsen. You can manage that with transfusion therapy. But is it more likely, in the scheme of things, to result in a better overall outcome by treating earlier in the disease course rather than one based on, historically, either symptomatic disease or whatever you define as rapidly changing counts?

FLEISCHMAN: I agree. What would…support that would be some secure data to say putting somebody on a JAK inhibitor will change their disease trajectory. That is [a difficult claim to make definitively] at this point. Unless you are sure that the treatment you are giving [the patient] is going to be beneficial to change their disease trajectory, it is difficult to put somebody on a treatment that is going to make their current problem—anemia—worse. Do you believe that a JAK inhibitor will alter the natural history of the disease?

TALREJA: No. JAK2 inhibition does not alter the pathophysiology or the bone marrow situation with myelofibrosis. It just improves the splenomegaly and they feel better, but I have never seen a JAK2 inhibitor change the physiology of the disease.

FLEISCHMAN: From my perspective, JAK2 inhibitors help with certain aspects of the disease, but I do not think we have clear-cut evidence that they change the disease physiology or trajectory.

BAGHIAN: I have never used it outside the indications, but I am always curious to know whether JAK2 inhibitors [affect] a patient’s hemoglobin in a beneficial way. Have you ever seen that?

TALREJA: I have never seen that.

FLEISCHMAN: I have seen, once or twice, in a post-PV patient who reverted slowly to their PV phase, who was having chronic inflammation that was contributing to their anemia; when I gave them the JAK inhibitor, it alleviated that. One patient asked, “Do you think I am going to need phlebotomies again?” But that was a single case. A second case was a patient who, at presentation, had a horrible gastrointestinal bleed. I think that is probably why he was anemic to begin with.

When do you consider clinical trial enrollment? Who do you send for clinical trials?

TALREJA: When you have exhausted all the treatments.

BAGHIAN: The poor-risk patients, for sure.

FLEISCHMAN: Do you feel the impetus for sending to the clinical trial is more the patient’s medical condition or personality—that they are asking for something else? How many times is it patient driven? Or you tell them, “Medically, this is very complicated and I do not have anything to offer; I think you need to go to a clinical trial.”

CHANDURI: I think since the cases are so few, and as a general practitioner I do not see them that often, I will refer them to a tertiary center where they are seeing more of these patients, at least for initial consultation, and then follow them. Because in our practices, we hardly see patients with myelofibrosis—only by diagnosis. I do not know about others. Unless they are running a completely hematology clinic, it is not a common disease that we all see.

CHAND: I agree. I think every patient should have access to clinical trials if there is one enrolling in the vicinity. We do not always have open enrolling trials, especially for these less common disease states. First line, second line, whatever it is, it is always good to have a patient go on a study if it is available locally.

FLEISCHMAN: How do [individuals] find clinical trials? Given that myelofibrosis is pretty rare, it is not like you are going to say, “Oh, I sent another patient for this trial last week.” What would you do, search clinicaltrials.gov, or what?

CHAND: I do search clinicaltrials.gov a lot. But sometimes there are places that reach out to you, especially if they have a trial that is open and enrolling. I have had providers reach out for rare diseases like paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria…where they are looking for patients. I generally keep that in mind when I see a patient with one of these rare hematologic conditions.

CHANDURI: I just send them to the tertiary center their insurance is contracted with. That way they will get a second opinion, and if they do not have any clinical trials with some kind of management treatment options, they will send them back to us and we can follow them. That is the way I think. I do not want to look for a trial for which they may or may not be eligible.

SASTE: I usually send them to City of Hope [Comprehensive Cancer Center in California]. That is our center.

BAGHIAN: I usually try to find someone I know who has an active laboratory in this field. It is hard [to find] someone such as yourself; or at UC San Diego Health [in California], I have Rafael Bejar, MD, PhD. I will ask him, “Do you have a clinical trial for this?” And if he says yes, then I will look for this.

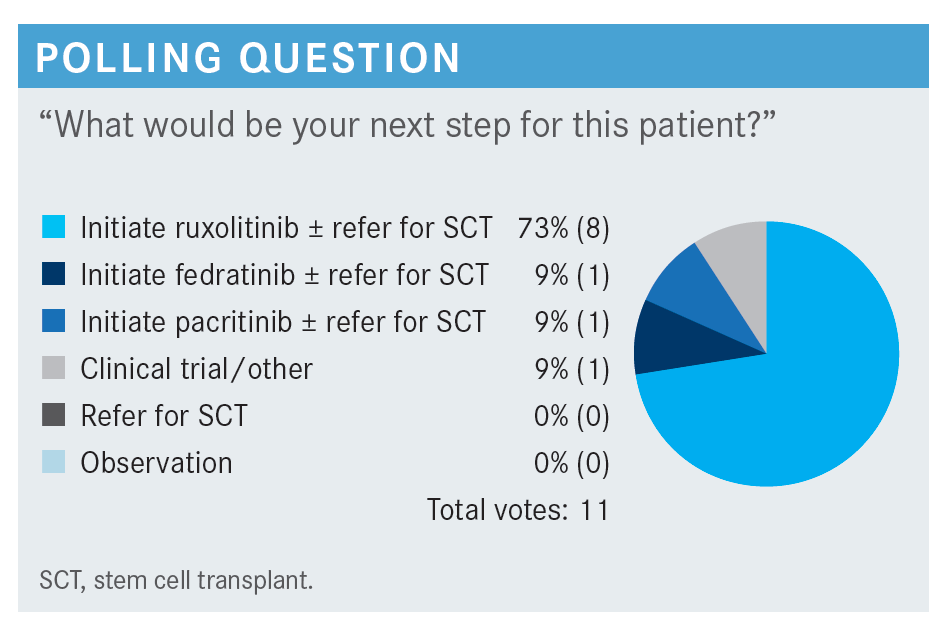

FLEISCHMAN: Most [individuals] selected a JAK inhibitor plus referring for stem cell transplant. There was a long period when all we had was ruxolitinib, and then fedratinib came around, and pacritinib came around recently. Now we have more options for JAK inhibitors.

Does anybody want to say why they chose the JAK inhibitor that they did?

TALREJA: I chose pacritinib because the patient is already anemic. I do not want to make them [more] anemic. They are already in trouble. I have had problems with ruxolitinib and anemia—impossible to keep on transplant. I do not want to transfuse these patients, so I chose pacritinib because that is going to improve her anemia too, and not make her more anemic.

CHARU: I have a patient exactly like this right now, who is 70. I started him on ruxolitinib; even though he was anemic, he was also getting epoetin alfa, and he is going to get a transplant now. I am more used to ruxolitinib, so I just started him on that because he had a big spleen.3

FLEISCHMAN: That brings up the question of using something that you have been familiar with for the past decade, you know how to dose it, and you know what to expect with the drug vs using a new drug.

CHAND: I have had patients who have needed to be on epoetin alfa or epoetin alfa-epbx [Retacrit] just to help with the anemia. We have all used ruxolitinib for a long time. Because pacritinib is the newest kid on the block, I have not used it. I chose ruxolitinib because we have used hydroxyurea and then ruxolitinib; those have been the 2 most common drugs apart from best supportive care, transfusion, and epoetin alfa for these patients for a long time.

Have you ever used 2 agents in combination, like ESA [erythropoiesis-stimulating agents] and ruxolitinib at the same time?

FLEISCHMAN: I have in a few patients. With ESAs, mechanistically, it does not make sense why they should work in somebody who has a JAK2 V617F mutation, which should be turning on erythropoietin [EPO] signaling. What is more EPO going to do for them? But nevertheless, I have had patients on both. I can’t tell you how beneficial the EPO really was.

CHAND: The whole discussion about ruxolitinib and anemia— since you see more myelofibrosis than the rest of us do, what is your experience with anemia in these patients? How bad does it get? What do you tell your patients?

FLEISCHMAN: I would say I am very up-front with them to begin with. I heavily select patients who I think are appropriate for ruxolitinib, and I am clear that it may worsen their anemia. [Many] will say, “Thank you very much, but no, that is not for me.”

There is the type of person whose symptom burden is so horrible that they would rather need transfusions and feel good than be on the ruxolitinib. I have a few patients like that; they say, “I will gladly take these transfusions because it makes me feel better.” But for the majority of [individuals], if they do not have horrible symptom burden and they do not want to become more anemic, I would not start them on it in the first place.

TALREJA: I have had patients who were transfused every 3 to 4 weeks, and eventually became iron overloaded, and it was difficult.

FLEISCHMAN: In the setting of ruxolitinib?

TALREJA: No, even without ruxolitinib. Then I went to androgens, and I went to danazol. I went to interferon. I had to transfuse every 2 to 3 weeks.

FLEISCHMAN: Unfortunately, the anemic patient with myelofibrosis is admittedly a very frustrating patient; you can throw stuff at them, but you are going to be lucky if you do anything for their anemia. In my mind, the anemia in myelofibrosis is an unmet need, where there needs to be some improvement.

TALREJA: I agree with you. We need to take up anemia more than the splenomegaly, because I do not think the problem is the big spleen. The problem is truly fibrosis and anemia.

REFERENCES

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Myeloproliferative neoplasms, version 2.2020. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://bit.ly/2Wcczfa

2. FDA approves drug for adults with rare form of bone marrow disorder. FDA. Published March 1, 2022. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://bit.ly/3yjYXRy

3. Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis.N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110557