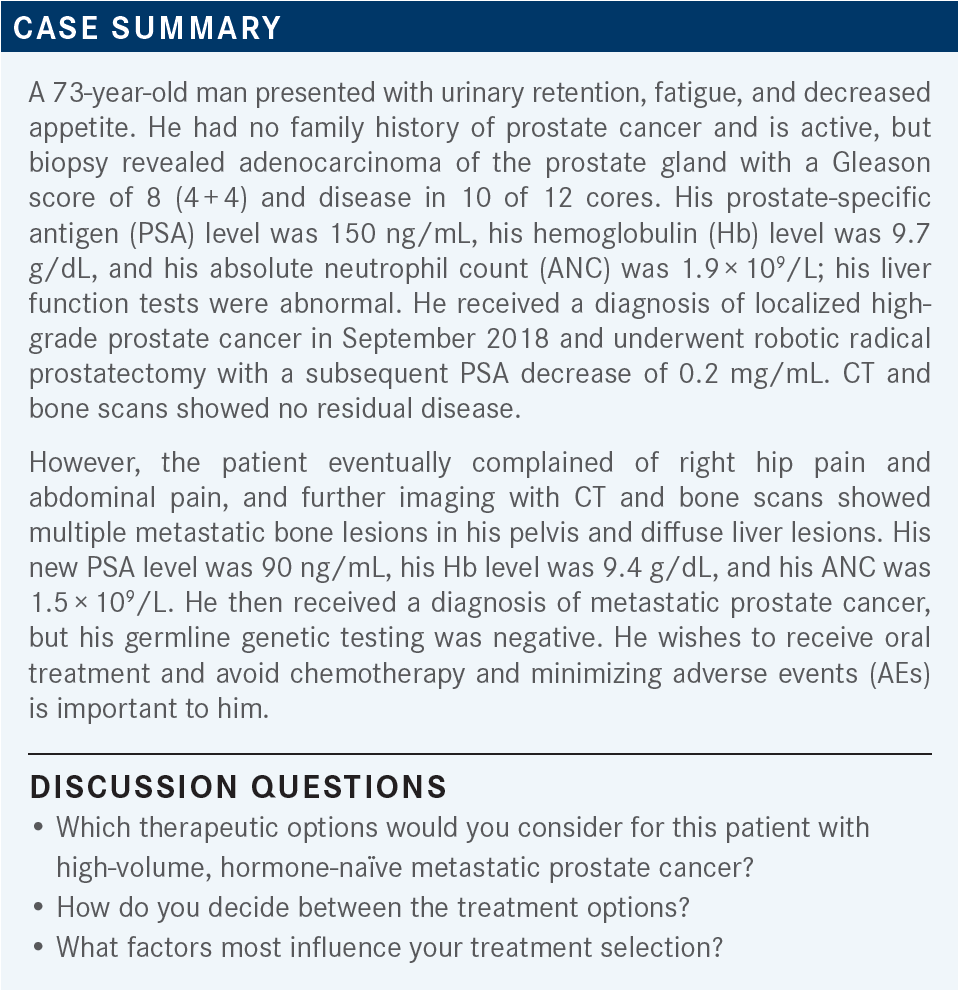

Roundtable Discussion: Bryce and Colleagues Consider Treatment Options in Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

During a Targeted Oncology case-based roundtable event, Alan H. Bryce, MD, discussed the case of a patient with high-volume, hormone-naive metastatic prostate cancer.

Alan H. Bryce, MD (Moderator)

Medical Director

Genomic Oncology Clinic

Chair, Division of Hematology/Oncology

Department of Internal Medicine

Mayo Clinic Arizona

Phoenix, AZ

HERMEL: It’s obviously based on patient preference. If they have high-burden disease, then you’re basically going to try to get something that would reduce the burden quickly.

That would be, ideally, something like chemotherapy with docetaxel [Taxotere]. The use of other therapies, such as abiraterone [Zytiga] and enzalutamide [Xtandi], would then be based on the AE profile and patient preference.

BRYCE: Is there a particular set of toxicity data that drives you when you think about the comparison of these drugs?

HERMEL: Yes, the patient’s baseline liver function for abiraterone.

STEPHEN: I am most comfortable using doublet therapies. I haven’t tried to use triplet therapies before, but for a lot of the patients I see I wonder if they could handle the toxicity of a triplet therapy. However, I do agree that you’d have to take into account the burden of disease, the pace of disease. I rarely use abiraterone now, as I’m very comfortable using enzalutamide. I am hoping to learn more about how to use molecular test results, because I’m not sure about that.

SUD: [For me, the most important factor is] predominantly…looking at patient preference. Many times, it also comes down to the cost of each drug and each program, and whether the patient can have assistance with any of these novel hormone treatments. But volume of disease, patient comorbidities, and cost of treatment are the predominant considerations that I have when I am choosing therapy.

BRYCE: [What I treat is] about 90% patients with prostate cancer and about 5% to 10% patients with testicular cancer, and the rest is a smattering of other things, a little bladder, a little renal. But here we do germline and somatic testing right from the beginning. As we saw in this patient, the germline was negative; the somatic is not reported. We did publish a paper evaluating the effect of the loss of tumor suppressor genes, [such as TP53, RB, and PTEN], and—no surprise—with greater loss of these genes, you get worse outcomes and an inferior response to androgen deprivation therapy [ADT]. So I often use that to help push me toward who should get chemotherapy, because ADT or hormone therapy alone won’t do it.

Having said that, I would have a certain bias in a man with heavy liver involvement this early on. We know that he’s headed toward a neuroendocrine phenotype quickly, one way or the other, and I would tend to get more aggressive if I could. But without question, frailty matters; without question, patient preference always matters.

But he is, by any standard, a high-risk patient. I guess that’s one of the things I always emphasize, [that] it’s not so much about volume, it’s about risk; and volume is one surrogate for risk. But the biggest, highest risk predictor that you can have would be de novo presentation over metachronous; this patient is metachronous, had his primary treatment first, and then had the metastatic disease. Beyond that, visceral disease also puts the patient in the highest risk category. This is a high-risk patient no matter how we want to look at this.

SURESH-CHANDAR: I think it comes back to a lot of the factors that we talked about earlier, like the comorbidities, performance status, frailty, and things like that. I think abiraterone or enzalutamide—which can produce a reasonably good response in a lot of patients, for a lot of people who are not interested in chemotherapy or unable to tolerate the AEs of chemotherapy—are good options, particularly if they have a lower burden of disease or are of advanced age to begin with. So those preferences do come into play, depending on patient factors, but if it was a young patient with a high burden of disease I would certainly push for up-front docetaxel or triplet therapy.

BANSAL: There’s no perfect answer; it just depends on patient age, patient preference, comorbidities, and tumor burden. I have patients who are 90 years old with de novo metastatic disease and other patients who are 56 years old. So it depends on, mostly, their comorbidities, age, and the treatment goals.

GOLDFARB: Most patients don’t want chemotherapy when you bring it up, so you must discuss that with them. My options for this patient would be chemotherapy, and anti-androgen therapy, but I would certainly want to discuss chemotherapy. After that, you’ve got to start thinking about PD-L1 or PARP inhibitors if the patient is BRCA positive.

YOO: I think the patients don’t like the word chemotherapy. There’s a benefit to using aggressive chemotherapy, so I try to convince them [to use it]. If the patient is concerned about toxicity, then I can always start on the lower dose, but I try to do chemotherapy if the patient has visceral disease. If not, I don’t think there is a wrong treatment.

SARACENI: For this patient I would be worried because there was possibly some impending liver failure, with bulky disease in the liver. With a younger, fit patient I would try to push toward chemotherapy; but, like most of us said, if patients have any other option but chemotherapy, they’ll do it. So I take patient preference and what they want to do highly into account when I counsel them.

GONZALES VELEZ: A perception that I see is that patients think that chemotherapy is like a taboo or a stigma word, and they think that targeted therapy, especially oral therapies, don’t have AEs. Sure, they are different from chemotherapy, but they can also have AEs. So I think it’s important to explain to patients that targeted therapies or hormonal therapies also have AEs, different from chemotherapy but they also have their issues.

BRYCE: Yes, absolutely. People come in with preconceptions: Why is 5-FU [fluorouracil; Adrucil] scary but capecitabine [Xeloda] isn’t? It’s the same drug, but there is that oral-intravenous [IV] divide. There’s also the semantics of what is chemotherapy vs what is a targeted therapy. So absolutely, there’s a lot of power in words, and I think we see that in the clinic every day.

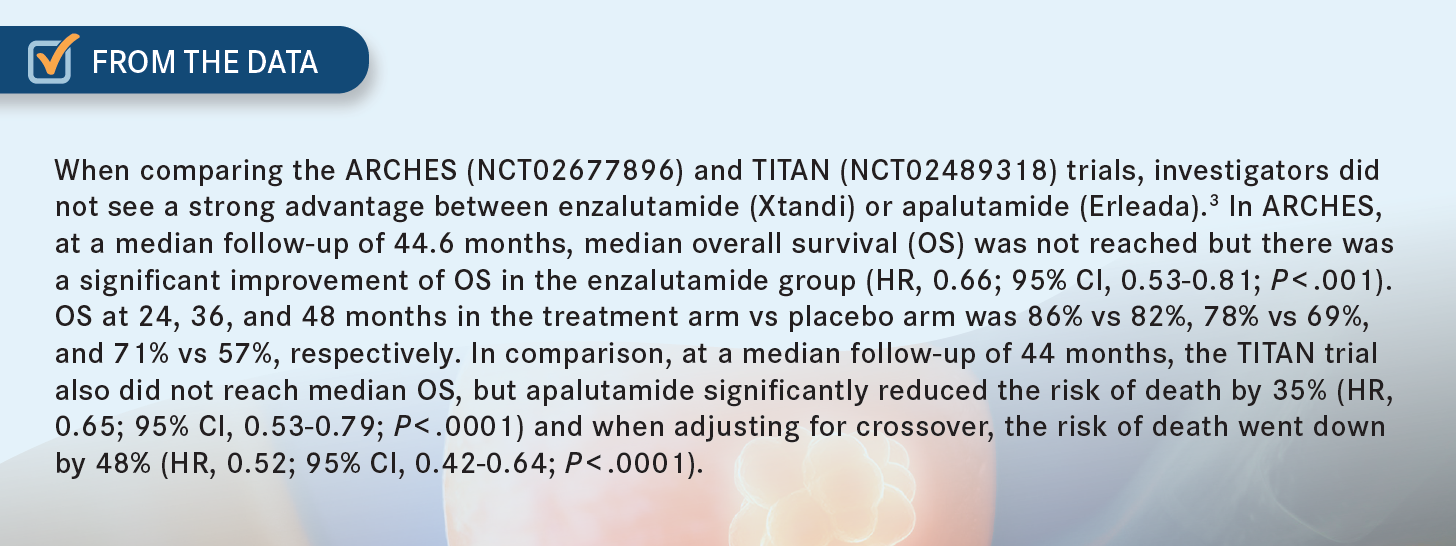

MAR: I think that all oral therapies are equivalent per the data that’s been reported in large, randomized phase 3 trials. So there are no preferred agents in terms of effectiveness [From The Data3]. I typically pick based on toxicity and insurance reimbursements.

But there was 1 small study that looked at sequencing of therapies in the castrate-resistant setting.4 And just knowing about AR-V7 mutations, [findings from] that showed that giving abiraterone before enzalutamide may lead to a slight chance of response to enzalutamide down the road, as a second therapy, and vice versa. I think the chance of response was 0% in that small study, so it was a little different in terms of setting because this is hormone-sensitive disease. I do gravitate toward abiraterone or apalutamide most of the time, less so with enzalutamide. More recently I’ve been using triplet therapies rather than doublet therapies. So not so much apalutamide single agent anymore.

HSU: Yes, I agree, most of us are comfortable using both. I’ve been using a little bit more of enzalutamide plus ADT lately, but I think the cost is the issue. I think they’re not that different in terms of efficacy, from the [data from the] 2 studies, the TITAN and the ARCHES studies.

SUD: I have used enzalutamide much more [often] than apalutamide in my own practice, [so have more] familiarity with that. I am familiar with these data and I find that [the enzalutamide] is well tolerated. Fatigue is a big AE that many patients do complain about. Of course, we also must watch their liver function tests [LFTs] but otherwise, they are fairly well tolerated.

SPILLANE: I tend to use apalutamide. I think it’s a well-tolerated drug. With enzalutamide, early on when they were first talking about it, I did have a few patients who had falls, elderly patients. And then it became clear that there is some central nervous system penetration, and it’s not exactly clear why, but you have some older gentlemen who will either get dizzy or have a fall, or something like that. When I’ve run into that, I’ve ended up having to reduce the doses. You do see that also with apalutamide but probably less so with darolutamide [Nubeqa]. I’ve [become] comfortable using apalutamide and potentially adjusting doses in those older patients who get the dizziness, and even in those patients [in whom] you’re worried about high risk of fall.

STEPHEN: With apalutamide, you—as opposed to chemotherapy—watch the LFTs, probably with monthly labs, to make sure they’re not having worsening castration-related symptoms, as opposed to [when they’re on] docetaxel. I personally have had bad experiences when adding docetaxel on. It’s a lot of lower-extremity edema, especially with situations where you have to use prednisone. What I usually use is enzalutamide as opposed to apalutamide, and in men who are over 80 I haven’t had the fall issue, [as mentioned earlier].

BRYCE: What about imaging? What do you do for imaging in these patients? [How do imaging and other findings trigger you to consider changing therapies?]

STEPHEN: This person’s advanced in this case, so every 2 months you might get CAT scans and a bone scan, or a PET scan. It depends on the pace of the disease, however, I have a hard time adding docetaxel on to these regimens. I’ve had a few cases where they are already too symptomatic from the prostate cancer by the time they presented. If you’re adding docetaxel, you must follow them much more closely.

SURESH-CHANDAR: You are going to be monitoring the PSA [level] closely, and if you’re seeing a rising PSA, or onset of any new symptoms, then that could potentially prompt you to get imaging to get a better understanding of the disease status. But a combination of those things usually triggers me to consider changing or adding therapy.

VELEZ: We have discussed the importance of the timing of the oral medications vs chemotherapy. You tell them about the toxicity, the steroid component, the fall risk with the enzalutamide, and the hypertension. You tell them the red flags and the risk factors that they should be on the lookout for and to call the office if anything happens.

I pretty much trust the patients that they’re able [to adhere], but I let them know they can skip 1 dose here and there, to give them a little bit of flexibility. I trust most of the patients when they tell me that they stopped the medication or they skipped a few doses. I think with a good physician and patient relationship, most of the patients are honest when they skip or if they stop the medication for any reason.

Now, what percentage of patients who are referred to you have already begun ADT monotherapy for their metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer [mCSPC]? We’ve got a variety. When it comes to GU [genitourinary] practices, and the relationship with the urologists and the radiation oncologists, I always say if you’ve seen 1 practice, you’ve seen just 1 practice, because every situation is different. I guess anybody who has most of their patients coming in already on ADT [would ask], what’s the nature of your treatment pattern? Who’s starting these patients on ADT? Just make it an open question [as you discuss next steps for treatment].

GOLDFARB: In my practice, the ones I see from urologists all the time are on ADT. I’ve never seen them not getting leuprolide [Lupron] when they’re from the urologist.

BRYCE: Do the urologists then ship them right away because they’re metastatic, or is that something that happens later?

GOLDFARB: In my practice, it’s after they relapse or treatment is no longer working, and then I see them. I never see them up front from the urologists.

SARACENI: I personally have not used triplet therapy in my practice yet.

BRYCE: If I saw a patient like this in my practice, I would be thinking to myself, “Triplet is what I ought to do,” and then I would have to convince myself why I wouldn’t. It might be because of patient preference, of course; might be liver function, etc, but it’s always on my mind.

You want to get that fast response when you have these aggressive diseases. Apalutamide and enzalutamide are great drugs, there’s no question. They’re effective, they’re well established. Reflecting on some of the comments earlier, I don’t feel like there’s a lot of daylight between the 3 oral options in terms of their overall efficacy. Choosing between the oral agents is largely a question of toxicities, tolerance, and then insurance coverage. Every now and then, you get some insurance company that prefers one over the other.

MAR: I’ve been using abiraterone/docetaxel based on the PEACE-1 data [NCT01957436],5 but I do think darolutamide is probably a little more tolerable from previous experience. So I would like to use darolutamide now if insurance will allow me, but I think that triplets are coming, and that’s the future for this space.

BRYCE: Yes. They managed to do ABVD [doxorubicin (Adriamycin), bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine] for patients with breast cancer in the ‘70s, and we’re still tiptoeing toward combination therapy in prostate cancer. They did that before there were antiemetics.

MAR: I also think it’s interesting that patients accept chemotherapy just fine if they have breast cancer, colon cancer, or pancreatic cancer. So why is prostate cancer so different, because breast cancer is also hormonal driven and patients accept chemotherapy just fine?

I think maybe that’s a way to think about it, we just have to educate the patients that if you get such an improvement in efficacy metrics, then why are we not giving chemotherapies in mCSPC together with the second-generation hormonal drugs?

BANSAL: If you have a younger patient who’s on docetaxel in the front line for de novo metastatic disease and is doing well, would you add darolutamide before the sixth cycle so that you could keep him on it, rather than just ADT after 6 cycles?

BRYCE: So far, the darolutamide label hasn’t been expanded, so I’m not sure I could get it approved. I’m hoping we’ll see a label expansion and we can get it in the metastatic castration-sensitive space, because right now it’s approved for nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. I think it was a good study, with clean data; I expect there’s going to be a label expansion and National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] recommendations. So I think in the future I’ll be comfortable adding darolutamide in that space.

But as of today, I’m doing docetaxel followed by abiraterone, because that’s the PEACE-1 data and you can get it approved.5 We’re doing docetaxel in about 20% of the patients overall, and doublet in about 80%. That practice is driven in a large extent by thinking about risk. Obviously, if we think someone’s headed toward neuroendocrine disease, then we’re jumping in with chemotherapy much earlier and also looking at the genomics. That’s not standard of care, that’s not in the NCCN guidelines, that’s just the result of having looked at several hundred of these reports in castration-sensitive disease.

But I’m not shy about docetaxel because we use it; we use chemotherapy in every other cancer, don’t we? And I agree with that point [that] it’s just a strange cultural phenomenon that we somehow think patients with prostate cancer are uniquely vulnerable to chemotherapy toxicity. If they’re 92, [that’s] fair, I understand; but [for] a standard 70-year-old patient, you wouldn’t hesitate to give them FOLFOX [fluorouracil, leucovorin calcium, oxaliplatin] if they had colon cancer. Why is docetaxel more toxic than FOLFOX? It’s not. However, darolutamide [I wouldn’t use] so far in this situation, but I think that’s coming quickly.

REFERENCES

1. Chi KN, Chowdhury S, Bjartell A, et al. Apalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: final survival analysis of the randomized, double-blind, phase III TITAN study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(20):2294-2303. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.03488

2. Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, et al. ARCHES: a randomized, phase III study of androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(32):2974- 2986. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00799

3. Ong S, O’Brien J, Medhurst E, Lawrentschuk N, Murphy D, Azad A. Current treatment options for newly diagnosed metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer– a narrative review. Transl Androl Urol. 2021;10(10):3918-3930. doi:10.21037/ tau-20-1118

4. Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Wang H, et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):1028-1038. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1315815

5. Fizazi K, Foulon S, Carles J, et al; PEACE-1 investigators. Abiraterone plus prednisone added to androgen deprivation therapy and docetaxel in de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (PEACE-1): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study with a 2 × 2 factorial design. Lancet. 2022;399(10336):1695-1707. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00367-1