Roundtable Discussion: Tripathi Assesses Decision-making for Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

During a Targeted Oncology™ Case-Based Roundtable™ event, Abhishek Tripathi, MD, discussed with participants their approach to treating patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Abhishek Tripathi, MD (Moderator)

Associate Professor

Department of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research

City of Hope Cancer Center

Duarte, CA

CASE SUMMARY

A man aged 75 years presented with intermittent right hip pain. His physical examination was unremarkable except for a prostate nodule on rectal exam and he was given an ECOG performance score of 1. His prostate-specific antigen [PSA] level was 32.6 ng/mL and his TRUS biopsy Gleason 4 + 4 grade group was 4. He had a negative bone and abdominal/pelvic CT scan and was diagnosed with stage cT2N0M0 disease. External beam radiation therapy and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) treatment were initiated and planned for 24 months; 6 months after initiation of therapy, his PSA level was undetectable, so he was considered asymptomatic.

Six months later—12 months after initiation of ADT—the patient scheduled an office visit and reported increasing hip pain and urinary frequency. His PSA level was now 29.4 ng/mL and he had a testosterone level of 10 ng/dL. His bone scan showed evidence of 2 new lesions in the right hip, at 0.8 cm and 1.1 cm each, and an abdominal/pelvic CT showed a 2.1-cm left pelvic lymphadenopathy and blastic lesions corresponding to the uptake on bone scan. He is now considered metastatic castration resistant, but germline and somatic testing were negative for pathogenic alterations.

DISCUSSION QUESTION

- What are you most likely to recommend now that the patient’s disease is progressing, with new liver involvement?

TRIPATHI: The options [to recommend] are abiraterone [Zytiga], cabazitaxel [Jevtana], and carboplatin [Paraplatin] combination; radium-223; repeat sequencing to assess for molecular alterations; or evaluate for 177Lu-PSMA-617 [Pluvicto] eligibility; or any other approaches and thoughts.

SCHAEFER: I think this patient may be appropriate for Lu-PSMA, because they failed a second-generation hormone. They’ve had a taxane in the metastatic castrate-resistant setting. I think it’s got the best data, even better than cabazitaxel and carboplatin, and it’s better tolerated, so I would do Lu-PSMA.

TRIPATHI: If you decided to do a repeat biopsy or more next-generation sequencing [NGS], can you elaborate on how you’re doing it? How often are you doing it? Do you use blood or just tissue?

ABDEL-KARIM: I don’t know [whether] one needs to repeat NGS if it’s done recently and they looked for the appropriate mutations, but one can repeat a biopsy if there is an unusual clinical scenario. I don’t think we’re dealing with small cell [histology] because he initially responded to docetaxel [Taxotere], then he lost the response. But you can always biopsy again if you’re suspicious.

HADDADIN: For the liver lesion, one should probably get a biopsy to rule out neuroendocrine differentiation.

TRIPATHI: For sure. I think that’s a reasonable approach, too. His cancer seems to be still making PSA, but he does have more aggressive features that make people concerned.

CASE UPDATE

The patient started treatment with enzalutamide at 160 mg given by mouth every day. His PSA decreased to nadir of 3.9 ng/mL 4 months after starting enzalutamide and his bone pain was resolved. After 8 months on enzalutamide, his PSA level was 60.7 ng/mL and another abdominal/pelvic CT showed enlargement of known pelvic lymph nodes. There was progressive disease on the bone scan with new lesions and he reported new back pain and progressive fatigue. His ECOG performance score was increased to 1.

The patient then started on 75 mg/m2 of docetaxel given every 3 weeks plus 10 mg of prednisone a day. The patient clinically responded with resolution of pain and improved energy, with a declining PSA. But with 4 cycles completed, the patient developed worsening conditions and there was neuropathy throughout therapy, so therapy was stopped during cycle; 5.3 months later, he had a rising PSA, new back pain, and shortness of breath on exertion. Abdominal/pelvic CT now shows enlargement of known pelvic lymph nodes and 1 new liver lesion (< 2 cm). NGS utilizing circulating tumor DNA was performed and showed no actionable mutations.

DISCUSSION QUESTION

- What treatment options do the NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) guidelines recommend for a patient like this?

TRIPATHI: Based on the most recent summary of castration-resistant prostate cancer [CRPC] guidelines from the NCCN,1 this patient falls into the category of [one who has] received prior docetaxel, responded but is intolerant to it, and can’t go back on it, and has also received prior novel hormone therapy.

A lot of us picked Lu-PSMA, which is a reasonable treatment option for this patient. Another option for this patient is cabazitaxel, which has shown an overall survival [OS] benefit in the postdocetaxel setting.2

A docetaxel rechallenge is perhaps not a good idea as this patient was intolerant to it. Then there [are] molecularly guided therapies with olaparib [Lynparza] and pembrolizumab [Keytruda]. I think we can all agree radium would not be a great choice because of the liver metastases. Are there any…preferences at this point based on the different choices that we have?

LOBINS: The only question I have is, we’re having an awful hard time getting the lutetium [at my practice]. We can get the prostate-specific membrane antigen scan done, but getting a treatment done is difficult. Are you bridging these guys with something, or what are you doing until they have lutetium ready for them?

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- How do you select next line of therapy for a patient with metastatic CRPC who has received docetaxel and an androgen receptor (AR)-targeted therapy?

- What factors do you consider when deciding on treatment?

TRIPATHI: I think that’s the meat of the question that we’re all facing in practice. Even though it’s approved, the availability and statistical challenges, especially in some parts of the country that we live in, can be…an issue.

ROSENFELD: I think this is what we do all day every day with people whether it’s [patients with] heavily treated lymphomas, breast cancers, or colon cancers. You’ve got to talk to the patient and see what they’re willing to do and assess their performance status and support at home, and factors like that.

TRIPATHI: Are any factors more relevant than others or that are specific to prostate cancer or this patient’s options?

ROSENFELD: I don’t think age plays a part in any of this. It’s their performance status, and what the patient desires. If they don’t have insurance coverage for lutetium, that certainly plays a role. Patient preference, financial considerations, and performance status; those are the top 3 factors, [in my opinion].

TRIPATHI: I think this situation is aggravated because we have an option of a chemotherapy agent and then a nonchemotherapy agent, which can have a second AR inhibitor, or lutetium. How’s the discussion with the patients, because there are different classes of drugs that are out there?

GUPTA: By the time we come to second-line chemotherapy, we are near the end of available approved therapies. By this time, there is a deterioration of functional status. There is increased disease burden, right? Having said that, whatever is available we should make sure the patient gets it. I found that cabazitaxel is quite well tolerated if one dose-reduces it, and it is clinically effective.

However, that has not been adopted in the US, but I have a great experience with it. I have seen patients tolerating it quite well. One just needs a lot more support for them. At the same time, we should look for clinical trials and see what’s on NGS testing. We try to do the best we can, but we are looking at conflicting things. At that point, patients want to make sure they maintain their quality of life, get enough time with their family, and pain control. All these factors come into play, but I do try to make sure that they’re aware of all available therapies.

TRIPATHI: I think you mentioned the point about accessing care and as far as the patients are concerned, oral agents may be a bit easier than chemotherapy agents that may be weekly. The distance is a big issue in this discussion, based on where the practice is located or where the patients live.

BALDEO: I have a practice in a rural area in Arkansas, in Harrison, and transport and logistics [are] an issue, so patients would rather have oral therapy than coming in for chemotherapy. Docetaxel is not an easy chemotherapy to take, so I feel like some of them are traumatized after that chemotherapy, and they don’t want to go for another chemotherapy. There’s a preference for oral agents in my clinic.

TRIPATHI: That’s a good point, and patient preference is informed based on prior experiences. The question gets a lot more complicated if they end up having a bad experience with the first-line chemotherapy that they got, just like this patient who had significant neuropathy from it.

DISCUSSION QUESTION

- What is your opinion of the CARD [NCT02485691] data as they stand currently? Do they influence your practice?

LOBINS: I use the CARD trial data when talking to patients all the time. The only problem that I had…is all these people had to fill an AR medication, but I couldn’t see [whether] any of them were checked for the AR-V7 splicing mutation. I’m not sure. I understand how the cabazitaxel worked. I agree with these numbers. I just don’t know how many of those people were destined not to do well because they already had the splicing mutation. It’s like in colorectal cancer giving somebody an EGFR inhibitor who has a BRAF mutation outside the BEACON trial [NCT02928224]. But if you know the medicine is not going to work, then it’s not a fair comparison and I couldn’t see anywhere that they were tested.

TRIPATHI: The trial didn’t select based on biomarker data because I think the AR-V7 story has evolved and now is in clinical practice. [Regarding] AR-V7, we use it from time to time, but it’s only one of the mechanisms with which these patients become resistant. So, they are a population that is not going to do well, but they are selecting for that patient population, so that was by design. Even if they are AR-V7 negative, there are other biological factors like RB1, or PTEN, or TP53 that can influence your outcomes on an AR-V7 inhibitor.

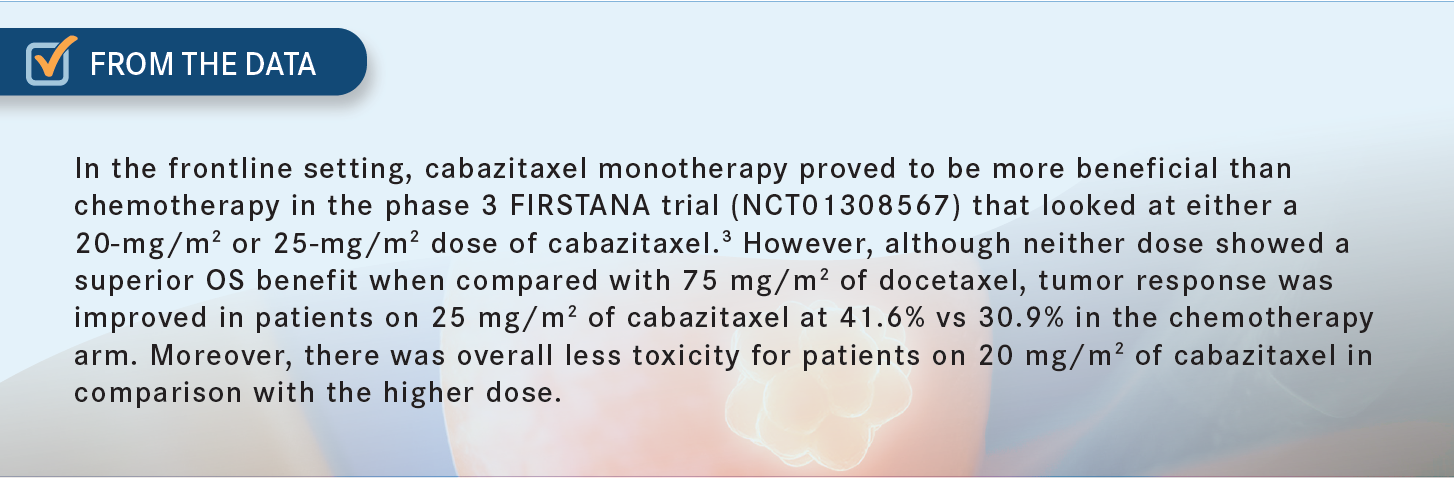

[The CARD] trial used selection criteria based on the patients’ historic response to a prior hormonal agent, and that was cut at prevalence, so they excluded 66% of patients. They selected the worst actors among all patients treated with AR-targeted agents [From The Data3]. Your comment is exactly on point, but I think we need to understand what else is driving that and learn a little bit more to understand that it’s not a 12-month cutoff. Understandably, it’s a group, and there’s a lot of different mechanisms going on in there and why the drug is not working. That’s something that we have learned over the past few years.

ABDEL-KARIM: I use cabazitaxel after docetaxel failure and sometimes early on [in the treatment process]. It’s a taxane derivative, and that’s the only FDA approval for the medicine.4

It has a role if somebody is older, I’m worried about docetaxel in their case, but I think they need infusion chemotherapy. It’s a good medicine. I think it’s falling out of favor but it has its role especially after docetaxel failure. I’m not sure these patients can be controlled with orals, especially if they have a progression quickly after docetaxel.

People could be rechallenged also with docetaxel as well after some time, but again, the medicine is underutilized. There [are] compelling data to show that it should be ahead of orals, but sometimes patients are tired; the oncologist says, “I’m not sure I want to push any more IV drugs, just try orals.” I present it to the patient and tell them I think this is a better option in terms of survival, but there are options for orals, too.

TRIPATHI: That’s a fair point. With the cabazitaxel OS data that we saw in the third-line setting and these data that also showed OS benefit, I think presenting it in context is important and it’s a shared decision-making between physicians and patients. There’s no wrong choice if we’re discussing all those points. Would anybody have any reservations about using cabazitaxel in somebody who didn’t tolerate docetaxel? We are talking about before we have the patient’s input. Would you recommend cabazitaxel in a patient who had neuropathy or a bad reaction to docetaxel?

SCHAEFER: I think you can do it with neuropathy. If somebody had an anaphylactic reaction to docetaxel, I’d be a little hesitant to do it. All the taxanes have some cross-reactivity, so if they had an anaphylactic reaction [I would not use it]. [If the patient experiences] neuropathy, you can try to get them through. I see more problems with cytopenia than I do with neuropathy with cabazitaxel.

TRIPATHI: That’s been the clinical trial experience as well, so your experience is right on point. Any additional insights on toxicities that you have noted in practice that are unique to cabazitaxel and any tricks on how people are managing it?

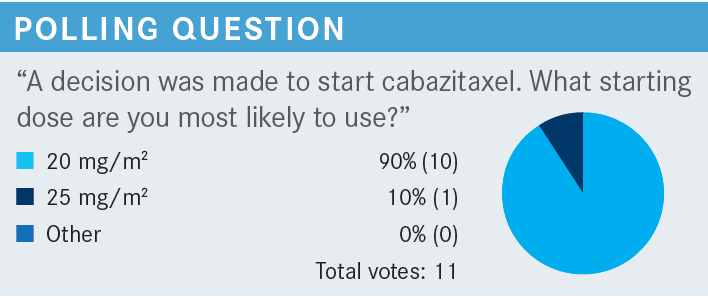

MATTAR: I’ve had [patients who had] issues with diarrhea. I’ve had one patient who had 1 treatment and had significant diarrhea but responded very well. His PSA level went down not only by a few points, but I always warn the patient [of the diarrhea]. We don’t use the high dose but the 20-mg/m2 dose, in that case.

TRIPATHI: Have people seen more myelosuppression compared with docetaxel, or how’s that experience been? I know the dose makes it a bit complicated.

ABDEL-KARIM: I think since reducing the dose with the recommendation to 20 mg/m2 instead of 25 mg/m2 we’re probably seeing less. Sometimes I still use granulocyte colony-stimulating factor with 20 mg/m2. Most of these patients have received docetaxel, so they could be heavily pretreated too, but…20 mg/m2 is better than 25 mg/m2, significantly.

TRIPATHI: Yes, and the tolerability is what most of our collective experience has been.

TRIPATHI: Most, as expected, would start out with 20 mg/m2, and some clinicians would start off at 25 mg/m2. I think that’s fair. Cabazitaxel and concurrent steroids can be considered for patients who are not candidates for docetaxel or were intolerant to docetaxel. Cabazitaxel is associated with lower rates of peripheral neuropathy, especially at the dose that we talked about, 20 mg/m2.

It may be appropriate as first-line therapy in patients with preexisting peripheral neuropathy. It is also approved for use in postdocetaxel second-line setting.5 The 20-mg/m2 or 25-mg/m2 dose can be used in those who have progressed despite prior docetaxel, and 25-mg/m2 can be used in healthy patients who wish to be aggressive because that’s where the original OS data came from. Growth factor support may be needed, and it is, at least in a lot of our practice, incorporated even with the lower dose.

The newer bit of data was perhaps the combination of cabazitaxel and carboplatin.6 So, this combination with cabazitaxel at 20 mg/m2 and carboplatin of 4 mg/mL per minute with growth factor support can be considered for patients with aggressive variant prostate cancer or unfavorable genomics.

REFERENCES

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Prostate Cancer, version 1. 2023. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://bit.ly/3XEad7h

2. Ojima I, Lichtenthal B, Lee S, Wang C, Wang X. Taxane anticancer agents: a patent perspective. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2016;26(1):1-20. doi:10.1517/13543776.2016.1111872

3. de Wit R, de Bono J, Sternberg CN, et al; CARD Investigators. Cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2506-2518. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911206

4. Mishra A. Benefit of cabazitaxel in previously treated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; CARD trial. Indian J Urol. 2020;36(4):329-330. doi:10.4103/iju.IJU_160_20

5. Lheureux S, Joly F. Cabazitaxel after docetaxel: a new option in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Article in French. Bull Cancer. 2012;99(9):875-880. doi:10.1684/bdc.2012.1617

6. Corn PG, Heath EI, Zurita A, et al. Cabazitaxel plus carboplatin for the treatment of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancers: a randomised, open-label, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(10):1432-1443. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30408-5

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More