Roundtable Discussion: Dowlati Breaks Down Updated Treatment Data in SCLC

During a Targeted Oncology case-based roundtable event, Afshin Dowlati, MD, discussed with participants the results of the CASPIAN and IMpower 133 trials of new regimens for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer.

Afshin Dowlati, MD

Associate Director for Clinical Research

Professor, Department of Medicine Division of Hematology and Oncology

Case Comprehensive Cancer Center

Cleveland, OH

MARINELLA: Before lurbinectedin [Zepzelca], which I’ve used in probably 4 or 5 patients, nothing worked. I use it as second-line therapy. The responses I’ve seen are short lived, so I would say after first-line therapy, there’s just a paucity of drugs that have meaningful response. I think that’s a big challenge.

ELKHATIB: I think the major challenge is the disease itself, the aggressiveness of the disease, and the comorbidities that come with the patient, for the initial treatment.

DOWLATI: The comorbidities that you’re seeing in patients are challenging.

SENDILNATHAN: The greatest challenges, when we move on to second-line therapy, include the performance status being extremely poor because by the time patients are done with their first-line therapy, are on maintenance, and are trying to get back to their baseline performance status, they have a disease recurrence. The performance status before starting second-line therapy is a great challenge.

Also, choosing among the second-line agents, like my colleague had mentioned. How do we choose among the agents that are available like lurbinectedin, topotecan [Hycamtin], or a combination of immunotherapy? On what basis we choose them is the other main challenge.

CHOWDHARY: I think we all appreciate that this is a very aggressive disease. After many years, with the advent of immunotherapies in SCLC, we’ve moved the needle a little bit but it’s not a home run by any means, right? There’s still a great challenge to come up with treatments that can render us much longer progression-free survival and overall survival [OS]. Even with our immune therapies, I think we’re not there yet. There is another side of the coin that’s a challenge. We all have a few patients who keep going on immunotherapy for almost 2 to 4 years, and they remain disease stable.

I [wish we could identify] what characteristics in their tumors have rendered them such a long response to immunotherapy, but also trying to figure out whether there are any other adjunct therapies to immunotherapy where we can get those kinds of responses in a much larger and general SCLC population.

I think we’ve made some movement, but not enough, and we do have these long-term survivors. I have about 3 or 4 patients now who are more than 2 or 3 years out on immunotherapy for SCLC. What is different about them, and what can we use as an adjunct? Those are the things that I think about.

DOWLATI: The points that were brought up are: we need better second-line therapy; when we get to second-line therapy our comorbidities are too high, but sometimes we can’t treat them [because of poor performance status]; and even though immunotherapy has made an impact, we’ve got to identify who’s responding to them. We will address all those issues in our discussion.

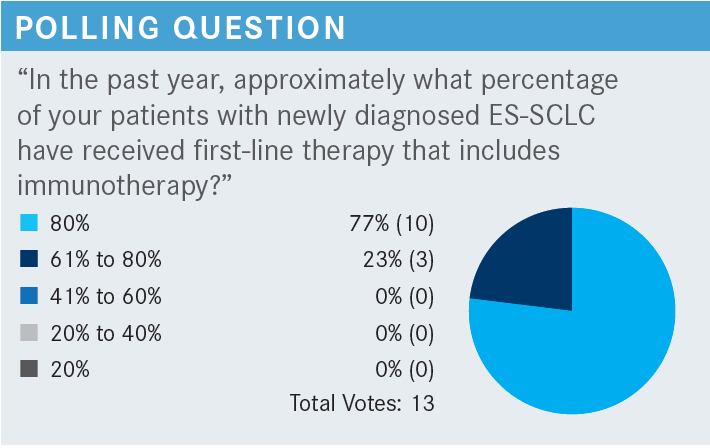

DOWLATI: What’s the reason for 20% to 40% of your patients not being able to receive immunotherapy for their disease?

SENDILNATHAN: I had a couple of patients, one of whom had multiple sclerosis [MS], so that is one main challenge I have seen in my patients so far. Especially when they are on immunomodulatory agents, it becomes a challenge for the neurologist and the treating oncologist to see whether it is worth putting them on immunotherapy when we know that chemotherapy is a bad one for SCLC.

Are we going to flare up their MS and make them paralyzed for the small benefit of the immunotherapy? That was a challenging situation that I encountered, but I would like to hear your thoughts about it. Is it worth it in such a patient who had a relapse probably like 1 or 2 years ago? What would be your cutoff for using immunotherapy?

DOWLATI: I fully agree with you. Certain underlying immune disorders are contraindications to the use of the immunotherapy. In the non–small cell lung cancer [NSCLC] world, almost 20% of the patient population has an underlying immune disorder like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or psoriasis.

For most of them, we’re comfortable giving immunotherapy nowadays, but MS is one for which many individuals are not comfortable giving immunotherapy. I agree with you: It’s not worth the risk. Anyone else have any reason why they don’t give immunotherapy sometimes? So, one is underlying immune disorders.

LANG: In certain circumstances we cannot give immunotherapy, even if we want to. For example, often the patients present in the hospital when they are very sick and [have just received a diagnosis]. You want to give chemotherapy plus immunotherapy but, just because of the hospital’s system, we cannot give immune checkpoint inhibitors [ICI].

DOWLATI: Great point. I think that’s a challenge that many oncologists have for patients who are being admitted for cycle number 1 of treatment because they have poor performance status.

Many oncologists are not able to give immunotherapy with cycle 1, but once the patient’s performance status improves and they come to the outpatient setting for cycle 2, that’s when most of us start adding immunotherapy for these patients.

Something I’ve been doing very often is giving immunotherapy starting in cycle 2 because I just can’t give it as an inpatient because of hospital rules and regulations, along with [the patient’s] performance status and many other factors.

BEED: I can think of a couple patients who had low thyroid hormone levels when we put them on immunotherapies. Then, they had another endocrinopathy, but they had so many that [the patient] finally wouldn’t survive if we continued it. They’re still in remission, but we had to stop it because of multiple endocrinopathies. Multiple, not just 1 or 2, it was work with each one.

DOWLATI: Good point. So, adverse effects [AEs], you started on it, but AEs are prohibitive in continuing it.

BEED: Right. Even with working with other doctors and endocrinologists, they had every “-itis” you can imagine.

DOWLATI: I fully understand. I have been there and done that.

BEED: But they did well when we had them on it for a little while.

DOWLATI: Absolutely.

MARINELLA: I do, but it’s not useful. Most of them have RB and TP53 mutations. I don’t think it’s ever led to change of therapy, and the TMB [tumor mutational burden] and MSI [microsatellite instability] are irrelevant.

However, even though those are pretty much nonplayers, I still do them probably just to look for a needle in a haystack, but I don’t think it changes much. I’ve never had it change anything because you give an immunotherapy anyway, so MSI and TMB don’t matter.

DOWLATI: I agree with most of you that there’s nothing outside of standard-of-care that one would do. Genomic studies and circulating tumor DNA are not things that inform us currently, but stay tuned, I think that may change in the next 1 or 2 years.

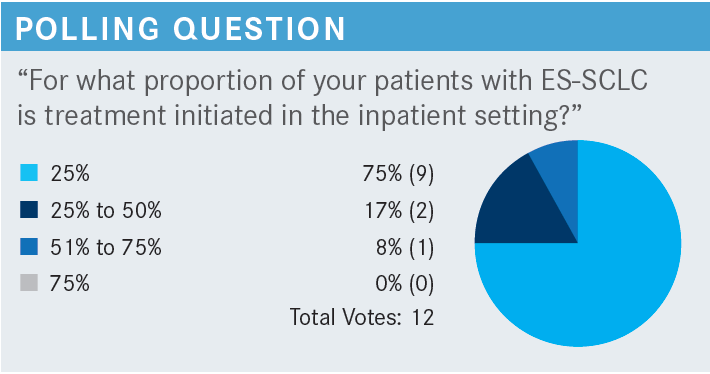

DOWLATI: In my practice, it’s probably close to 30% or 40% simply because of the tertiary nature at times, and patients being transferred from other hospitals to us for treatment. However, I do agree that it’s probably somewhere around 25%.

What would be your approach to treating this patient? What factors influence your recommendation? How would you counsel this patient regarding their treatment options and how do you consider the most important points to communicate [to them]?

PATIL: Whenever I meet a patient like this, one of the first things I convey is the fact that this is an aggressive cancer and to set their expectations and goals with treatment, in terms of life expectancy. That can sometimes help patients make decisions when we talk about treatment options and what the potential AEs might be. Certainly, for this patient, who has an ECOG performance status of 1, in the absence of clinical trials available at the time, I would recommend standard-of-care platinum-based therapy, probably carboplatin [Paraplatin], etoposide [VePesid], and immunotherapy. But like I said, I always begin with what to expect, what treatment, and what the evidence shows in terms of median OS. This helps the patients make the decisions that they need to make, whether that is what they would want for themselves, or depending on how they’re looking. This patient has a preserved performance status despite being very symptomatic, but many other patients might choose to forgo treatment.

ALVAREZ: I’ve seen that one of the things with this illness is the patients feel very deceived, because initially we can have a great response, and then suddenly they can change in a few months, or quickly. So, try to follow up and keep the patient on the same page. Let them know that they can have a great response at the beginning, but then, that may not happen later. I think that’s one of the hardest parts for me as an oncologist, treating these kinds of patients, because they feel great after the first initial treatment, and then we start seeing things that we don’t like to see. I find that this is very particular for SCLC.

DOWLATI: Based on the 2022 NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines for ES-SCLC, the preferred regimen is carboplatin, etoposide, and atezolizumab [Tecentriq] followed by atezolizumab maintenance, or carboplatin, etoposide, and durvalumab [Imfinzi] followed by durvalumab maintenance. There is the option of giving cisplatin [Platinol], etoposide, durvalumab, and durvalumab maintenance. I use cisplatin in some patients. If you decide not to give immunotherapy, give just carboplatin or cisplatin plus etoposide. Rarely, patients can’t receive etoposide because of a variety of issues; in those cases, we always go with irinotecan [Camptosar], a topoisomerase I inhibitor, in combination with a platinum.1

How do you decide between carboplatin and cis-platin in your regimen when using an ICI-chemotherapy regimen for SCLC?

MARINELLA: I rarely do, but maybe in young patients with not a lot of metastatic disease and minimal medical problems, I’ll use cisplatin, but it’s not a common occurrence in SCLC. If it’s a young person with maybe 1 brain metastasis, we may consider stereotactic radiosurgery. [Data are scant] and I understand that there’s a lot of microscopic disease potentially, but in the rare patient, I will. It’s a little bit better, but generally not a whole lot.

BEED: I disagree. I would never use cisplatin except where we had a patient on carboplatin, and he had a reaction and we put him on cisplatin and he’s doing fine. But over the years, I’ve heard where cisplatin should be used. I’ve done this for a lot of years. Everybody says cisplatin’s better; I just don’t feel it is. I think with the neuropathy and everything else, the patient’s probably not going to be cured unless something new comes out that’s drastic. So, you’re going to have that neuropathy and everything else that goes with it and what is the patient going to gain when he’s probably not going to do any better anyway? It is probably, but not always, going to be terminal. The other thing is, for baseline, I check for [chromogranin A (CgA)], and if it’s negative, that’s fine, but if it’s positive, I check to see whether it starts going up.

DOWLATI: The issue of cisplatin and carboplatin, you are correct, some randomized trials have shown they’re equivalent. I use cisplatin in a very specific situation: when the patient presents with pancytopenia and marrow involvement. Randomized trials show that cisplatin is significantly less myelosuppressive than carboplatin, and so with patients who have bone marrow involvement and they come in with platelets of 30,000 to 40,000, I use cisplatin.2 But I agree: for everyone else, I use carboplatin for the most part.

CHOWDHARY: Certainly, [the data are compelling]. Especially because we’ve been through an SCLC [compelling data] drought, if you will, as we’ve not had any new treatments or any additive treatments that have moved the goal line. This is the first time we have treatment with some modest survival benefit. I think with these immunochemotherapies, you’re getting a 2-year survival, and it’s modest but still better than what our historical controls have been. I still feel, though, that [these are] positive data, and that’s why across the board now, chemoimmunotherapy has been adopted as our first-line regimen. I think it’s impacted all our practices, frankly. I wish new treatments down the pipeline can build upon this but, again, it’s a modest benefit. So, being the only benefit we’ve had in a long time, it’s been widely adopted.

DOWLATI: When you’ve had no treatment benefit for many years, and the last approved drug was topotecan, which officially was old enough to vote a couple years ago, it’s tough to not get excited about immunotherapy, even though it has only a 2-month improvement in OS. Is there any part of these data that anyone finds disappointing? Maybe the overall response rate is not higher? Or because we don’t have long-term data?

SENDILNATHAN: I would like to make a note and ask you a question about the data of the patients with brain metastasis, which did not show a significant benefit. [In the IMpower 133 study they] wanted these patients with brain metastases to be treated. I wonder whether the bad outcomes in this subgroup of patients are because the treatments were delayed?

For example, in the patient that you presented—the 73-year-old with an asymptomatic, single brain metastasis—I don’t know whether I would have sent her for radiation in the first place. If it’s a small brain metastasis and is asymptomatic, I would have just started her on systemic chemoimmunotherapy. I’m sure that my radiation oncologist would have agreed. I don’t know whether that made a difference, because we know chemotherapy’s does have some effect on the brain metastasis.

DOWLATI: There were only 35 patients, out of 400, who had brain metastases, so it’s tough to know whether the 35 patients impacted the study. Theoretically, because brain metastases were a stratifying factor, you would have gotten an equal number on both arms. I agree with you that in practice, most of us do not give brain radiation up front because chemotherapy is quite effective in treating brain metastases, but we reserve the brain radiation, whole brain radiation, or any form of brain treatment [until] after our chemotherapy has been completed. It’s just tough to know, I think there’s not enough patients on there. When looking at the CASPIAN study [NCT03043872] data with durvalumab that had almost double the number of patients who had brain metastases…they did allow asymptomatic untreated brain metastases to get in.

Now, does anyone want to explain whether they switched from atezolizumab to durvalumab, and why they did that? Is it because of the hospital policy?

MAHAJAN: I switched to durvalumab mainly because in the maintenance setting, it’s every 4 weeks. So, instead of 3 weeks, it is 4 weeks. The hazard ratio and everything from the trial data seem identical. I don’t think you can go wrong with any option, but I use durvalumab mainly because of the patient convenience, in the maintenance setting, so fewer visits to the hospital.

DOWALTI: What is your reaction to the updated CASPIAN data? Have they impacted your practice? If yes, how?

MARINELLA: I’ve not used durvalumab. I use atezolizumab a ton, and I’ve not had a lot of luck with it in any disease process. I have a patient who’s had sort of a prolonged response, but I’ve not been impressed with atezolizumab. That’s just my experience, which is somewhat anecdotal. So, I’ve not used durvalumab, but after seeing this, I need to check Epic Beacon because I might give it a shot.

My other question would be in the CASPIAN study, you said up to 6 cycles of chemotherapy, but for SCLC the paradigm is 4 cycles because I think the old data say that 6 [cycles] isn’t any better than 4. Do you think that has any impact, or is it impossible to say?

DOWLATI: I don’t think it had any impact, and I think we all agree that 4 to 6 [cycles] is equivalent. I think that was put in because some practices across the world tend to go for 6, but I agree with you that the data show 4 is equivalent to 6, and 6 is equivalent to 8. There are no data saying you need to give more than 4 cycles of chemotherapy. One of the concerns that I also had with atezolizumab is you don’t have luck. Its uptake in the NSCLC world is extremely poor. I have shared patients with many of you over the years, and most of us for NSCLC tend to use pembrolizumab [Keytruda] for stage IV disease, which is a more common regimen. Atezolizumab hasn’t picked up in both SCLC and NSCLC.

Before I switched to durvalumab, I had similar experiences with Dr Marinella, but is durvalumab any better? These are cross-trial comparisons, so you must be very careful in interpreting that. I made the move a few years ago, and I have some longer-term survival patients. What that means, I don’t know. Does anyone get excited with that near 20% 3-year survival rate in SCLC?

LANG: I think the CASPIAN data looked cleaner. The curves separated continuously after a certain period. Even though the number of patients in the CASPIAN trial is not too much higher than the IMpower133 trial, I used the regimen before some data came out because I just had the habit, and we’ve used that regimen. It’d be hard to change. I don’t want to try to compare across trials in the data, but it seems to me that the CASPIAN trial data looked cleaner, and I like the curve because it continued to be separated after long-term follow-up.

REFERENCES

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Small cell lung cancer, version 2.2022. Accessed May 11, 2022. https://bit.ly/3w6bsRa

2. Rossi A, Di Maio M, Chiodini P, et al. Carboplatin- or cisplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of small-cell lung cancer: the COCIS meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1692-1698. doi:10.1200/ JCO.2011.40.490

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More