Popat Discusses Different Aspects of Managing GVHD

During a Targeted Oncology case-based roundtable event, Uday R. Popat, MD, discussed the approaches to identifying and managing graft-vs-host disease.

Uday R. Popat, MD

Professor of Medicine

Department of Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy

Division of Cancer Medicine

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Targeted OncologyTM: What is the background and management of GVHD?

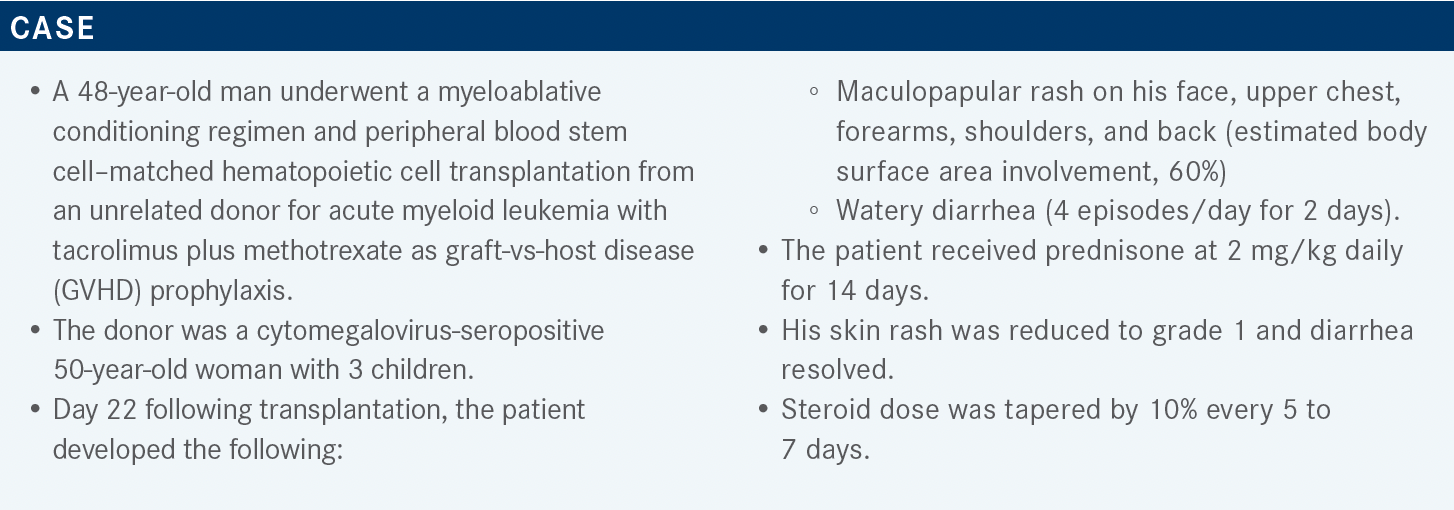

POPAT: GVHD is the leading cause of nonrelapse mortality or treatment-related death following allogeneic transplant. We recently did a study of 200 patients with a new regimen, looked at the data, and found that at day 100, about 5% of the patients had treatment-related mortality. Most were related to organ damage.

At 3 months to 1 year, [which is the point that] many of you will see these patients in the community, we had 15% additional mortality. So we lost about 24 patients in that period—22 of 24 of whom had GVHD at some point during their disease course. Many of them died of GVHD, but some developed severe infection because they were so immunosuppressed because of GVHD and its treatment.

The treatment-related mortality of transplant is due to GVHD. We need to bring it down to make transplant as safe as possible. Unfortunately, a lot of [clinicians] see these patients in the community because typically at the transplant center, we see them up to day 100. So if the mortality due to GVHD is occurring after 3 months or 1 year, I think it behooves you [to] have some familiarity with this disease.

So we will talk about both acute GVHD [aGVHD], which traditionally was defined as GVHD occurring before 100 days, and chronic GVHD, defined as that occurring after 100 days. They are different syndromes that we think of as 2 different entities: one that occurs early and 1 that occurs late, but with different manifestations.

With standard prophylaxis, about 50% of the patients still develop GVHD, so this is still a significant problem. Of these, about half do not respond to treatment. In addition to steroids used as a first-line therapy, some of the other treatments have a big role. When we condition patients with chemotherapy and radiation therapy [during transplant], this damages the normal host tissue because it is a highly lethal treatment, even more than regular chemotherapy. At 2 to 3 times the normal dose, this will cause toxicity.

So there is tissue damage, which exposes the normal antigens on the patient recipient host tissue that then attracts the donor’s T cells. The donor’s T cells see the antigens that are presented by the recipient, known as antigen-presenting cells [APCs] to the donor immune system. Then you have the T-helper 1 lymphocyte cell response, resulting in the release of cytokines and effector cells, which damages normal host tissue and causes GVHD.1

The typical target organs in aGVHD are 3: the skin, gastrointestinal tract [GIT], and liver. So you may see skin manifestations like maculopapular rash, lower GIT involvement like diarrhea, or nausea and vomiting, and liver abnormalities manifesting as elevated enzymes like alkaline phosphatase; but typically it is a cholestatic picture.1 For prevention, we typically try to suppress the donor’s immune system [by giving the recipient] cyclosporine and tacrolimus. These are called calcineurin inhibitors, and they inhibit the T cells. Methotrexate is the other agent that is used.

How does prophylaxis play a role in treating GVHD?

Most places do GVHD prophylaxis with tacrolimus and methotrexate. Others used include mycophenolate mofetil, sirolimus, [a T-cell antibody using] antithymocyte globulin [ATG] and alemtuzumab, and ex vivo T-cell depletion [with CD34 selection]. But more commonly, many centers including ours are using posttransplant cyclophosphamide, which has changed the GVHD profile. So depending on where you are, patients will receive tacrolimus, methotrexate or posttransplant cyclophosphamide and tacrolimus and then [mycophenolate mofetil].

The APC activates the T cell, and anything that stops this interaction will result in reduction of GVHD. So the first thing that you could do is just get rid of the T cells through ex vivo T-cell depletion. In a lab, we can take out all the T cells and give only stem cells, and you get rid of GVHD— but you end up with a different problem.2

The other alternative is you give antibodies like alemtuzumab or ATG, which reduce the T-cell numbers. There are some other agents that you could use too. You can suppress the cytokines, so you have drugs that inhibit the tumor necrosis factor receptor, such as etanercept [Enbrel] and infliximab [Remicade]. You could also use JAK [Janus kinase] inhibitors and inhibit multiple cytokines. Essentially, you can reduce the signaling that innervates the T cells.2

Are there institutional preferences for grading, staging, or risk stratification of aGVHD?

The stages [based on the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium (MAGIC)] go from 0 to 4. The higher the stage, the greater the severity. If the skin area involvement is more than 50%, it is stage 3. But if you have bullae or erythroderma, it is stage 4 and very severe.3 The details are not important. What is important is the severity.

If you have a very high [bilirubin of more] than 15 mg/dL, then it becomes stage 4, and for GIT symptoms, if you get more than [1000 mL of diarrhea per day], then it is beyond stage 2 GVHD. So stage 4 being more severe has a very high mortality of 80% to 90%.3

They are now dividing patients into standard risk vs high risk based on severity. The problem is that if you have high-risk disease, the response rate to steroids is lower. For pure standard-risk disease, there is an almost 70% response, but if you have high-risk disease, it is only 40%. The patients with high-risk disease have a higher treatment-related mortality at 6 months [of 44%], whereas that of the standard-risk group is 22% [P < .001]. This translates into overall survival too.4

You can classify GVHD based not only stage but on [a panel of 6] biomarkers.5 These are mostly in the specialized centers with interest in GVHD. Most centers do not even do this, but it is important from a GVHD research standpoint. The point here is that it differentiates those with high-risk and low-risk disease.

What is steroid-refractory GVHD, and how is it managed?

This is GVHD in a patient who progresses after steroid administration of 2 mg/kg or greater for 3 to 5 days or anybody who fails to improve within 1 week of treatment initiation.6 When you think of GVHD, start treatment quickly. Likewise, when you think about steroid-refractory GVHD, start treatment early.

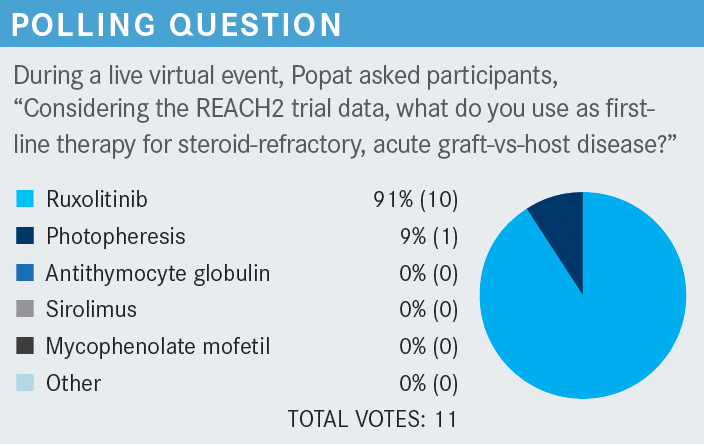

Based on the NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines, there are multiple agents used for steroid-refractory GVHD including infliximab. Extracorporeal photopheresis can also be done. But on top of the list is ruxolitinib [Jakafi], which is an FDA-approved agent.

Together with agents for chronic GVHD, a total of 3 agents are approved. For chronic GVHD, belumosudil [Rezurock], initially known as KD025, is a new one on the block, and ibrutinib [Imbruvica] is a drug we use for chronic lymphocytic leukemia too.7

GVHD is initiated by damage of the organ systems by the chemotherapy [that] drives the T cell or the donor immune system response, which is mediated by cytokines. One way to inhibit this reaction is by inhibiting cytokines at several levels and blocking the transmission of their signals. All cytokines use the signaling pathway called JAK kinase, STAT pathway, or JAK-STAT signaling pathway. These are the receptor tyrosine kinases, and when the cytokine is attached, it transmits the signal for their activation.

So, if you could block this pathway, you could reduce this reaction and reduce inflammation. Ruxolitinib is a drug that does that. You may have used it in myelofibrosis, where it causes a magical response.

I see a lot of patients with myelofibrosis who have a huge spleen, and they get ruxolitinib and the spleen goes down in size. In the studies, we saw that these patients started feeling better and started gaining weight because they had a drop in the cytokine levels. The first time we saw there was a reduction in the cytokine levels, many of us wanted to study this drug for GVHD because we knew that cytokines played a big role in GVHD.

What are the data behind using ruxolitinib in both acute and chronic GVHD?

In the phase 2 REACH1 study [NCT02953678], they found a benefit. So it was then taken to the phase 3 REACH2 study [NCT02913261], where patients with steroid-refractory acute GVHD were randomized to receive ruxolitinib or best available therapy [selected by investigators before randomization]. The end points were overall response at day 28. So a very simple design.8

At day 28, ruxolitinib had a 62% response rate as opposed to the controls at 39% [odds ratio (OR), 2.64; 95% CI, 1.65- 4.22; P < .001], which was statistically significant. The durable overall response at day 56 for ruxolitinib was also higher at 40% vs 22% for the controls arm [OR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.43-3.94; P < .001]. Patients with all grades of GVHD responded to therapy.9

Patients who got ruxolitinib had a better duration of response, and those in the control arm lost the response to treatment earlier. All the affected organ systems responded, and you did not see downshifting of the organs. Mainly in acute GVHD, skin and lower GIT [had better responses]. This resulted in better median failure-free survival in ruxolitinib of 5 months vs 1 month for the control arm [HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.35-0.60].9

Obviously, this is a drug that suppresses blood counts, so the incidence of thrombocytopenia was higher, which was also seen in some patients with myelofibrosis, and some anemia, although it was not seen in this study.9

What do you feel is something community physicians think about when treating patients with GVHD?

A take-home point from my standpoint for [clinicians] who work in the community, [the setting where] you are going to see the patient with aGVHD is...either if they are not controlled well at a university hospital or a referral center like ours and second, when we are tapering or reducing immunosuppression, particularly tacrolimus. So for a patient who has a recent change, drop, or stop in the immunosuppression agents and comes in with rash or diarrhea, think about GVHD.

Some of these patients also can have elevated transaminases, which in fact is another common manifestation of this withdrawal.

Point No. 2: If you are thinking about GVHD and the patient is significantly sick, after calling your local transplant doctor, probably think about using steroids. Then of course, if the steroids fail, ruxolitinib is an option; but you can let your referring doctor decide whether they want to use it or not. But you can certainly mention to them that this is a good agent.

REFERENCES

1. Hill GR, Ferrara JL. The primacy of the gastrointestinal tract as a target organ of acute graft-versus-host disease: rationale for the use of cytokine shields in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2000;95(9):2754-2759.

2. Choi SW, Reddy P. Current and emerging strategies for the prevention of graft-versus-host disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(9):536-547. doi:10.1038/ nrclinonc.2014.102

3. Harris AC, Young R, Devine S, et al. International, multicenter standardization of acute graft-versus-host disease clinical data collection: a report from the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(1):4-10. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.001

4. MacMillan ML, Robin M, Harris AC, et al. A refined risk score for acute graft-versus-host disease that predicts response to initial therapy, survival, and transplant-related mortality. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(4):761-767. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.01.001

5. Levine JE, Logan BR, Wu J, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease biomarkers measured during therapy can predict treatment outcomes: a Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network study. Blood. 2012;119(16):3854-3860. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-01-403063

6. Schoemans HM, Lee SJ, Ferrara JL, et al; EBMT Transplant Complications Working Party and the “EBMT−NIH−CIBMTR GvHD Task Force.” EBMT-NIH-CIBMTR Task Force position statement on standardized terminology & guidance for graft-versus-host disease assessment. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(11):1401- 1415. doi:10.1038/s41409-018-0204-7

7. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hematopoietic cell transplantation, version 4.2021. Accessed January 16, 2022. https://bit.ly/3ocIjNV

8. Jagasia M, Zeiser R, Arbushites M, Delaite P, Gadbaw B, von Bubnoff N. Ruxolitinib for the treatment of patients with steroid-refractory GVHD: an introduction to the REACH trials. Immunotherapy. 2018;10(5):391-402. doi:10.2217/imt-2017-015

9. Zeiser R, von Bubnoff N, Butler J, et al; REACH2 Trial Group. Ruxolitinib for glucocorticoid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1800-1810. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917635

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More