Exploring TKIs and Immunotherapy in the First-line HCC Setting

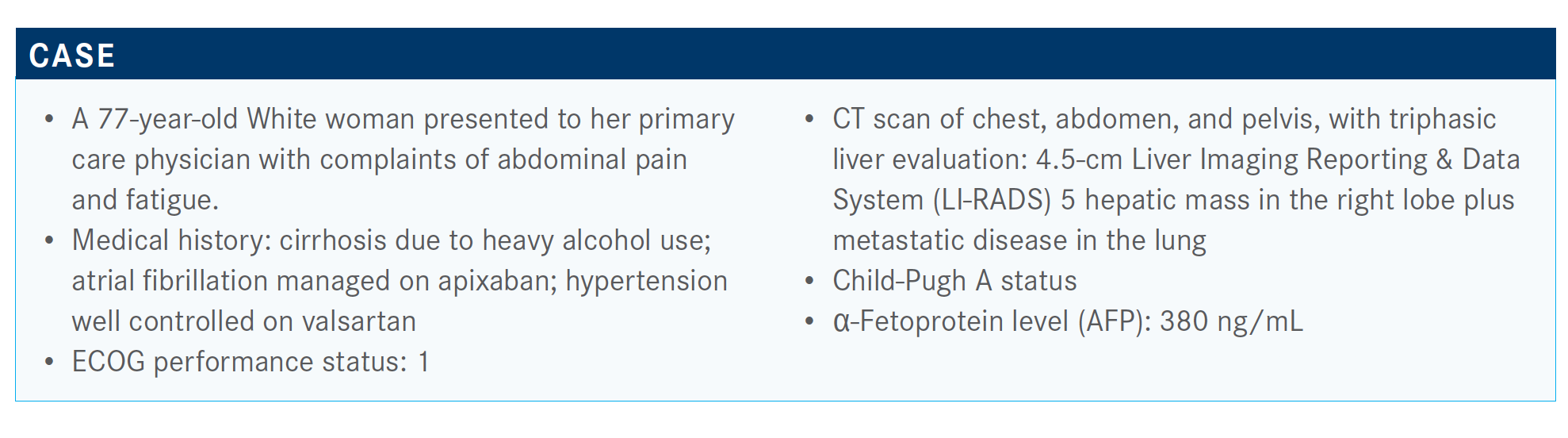

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Peer Perspectives event, Catherine Frenette, MD, discussed the case of a 77-year-old patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Catherine Frenette, MD

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Peer Perspectives event, Catherine Frenette, MD, medical director, Liver and Cell Transplantation, Scripps Center for Organ Transplantation and director of the Liver and Hepatocellular Cancer Program at Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center, discussed the case of a 77-year-old patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Targeted Oncology™: What role do the LI-RADS score and other markers play when deciding how to treat patients with HCC?

FRENETTE: LI-RADS is being pushed in the guidelines now as similar to mammograms with BI-RADS [Breast Imaging Reporting & Data System]. The data have been clear with LI-RADS 5 lesions. That’s 95% [likely] it’s HCC and 98% that it’s malignant. AFP is helpful if it’s positive. If it’s not positive, that doesn’t necessarily help you, because half of cancers don’t release AFP.

Whenever I’m doing my tumor markers, I always get AFP and a CA [cancer antigen] 19-9 [blood test], and if that’s elevated, then I worry and think about a biopsy. It can burn you sometimes. [With] LI-RADS B in someone whose AFP is 400, I would be suspicious, and we may not biopsy either. The data for LI-RADS were [obtained from] patients with cirrhosis, and there are not a lot of data [of its use] in patients without cirrhosis.

In someone without cirrhosis, sometimes biopsy is recommended. So that’s been interesting. We are seeing a big increase in cholangiocarcinoma in cirrhosis, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, so that’s always a concern as well. Then [with] LI-RADS 4 lesions, we’re not completely sure, but in someone with a high AFP we may not biopsy—we [discuss] it during tumor board [meetings] and decide.

There are not a ton of data on HCC with genetic testing and having it be predictive of what treatment options are going to work for the patient. For instance, we know PD-1 testing in the HCC trials—the PD-1 staining—didn’t predict which patients would respond to immunotherapies. There were patients who [had PD-L1 status of] less than 1% and they still responded and patients with more than 80% that didn’t respond at all. It’s interesting how different it can be with HCC. The thought in the discussions of the meetings I’ve [attended] is in HCC, the tumor itself can have multiple cell types and multiple genetic mutations. And it can be predictive in one part but not in another, and so the genetic testing has not been very helpful. I think it will be interesting once we get to circulating tumor DNA to see if that can be at all predictive. I know a lot of the clinical trials now are looking specifically for markers that will predict response. But so far nothing has panned out.

Would you do any further imaging for this patient?

We know that elevated alkaline phosphate is also predictive of poor outcomes. We’ll often do bone scans rather than PET scans because we know about half of patients with HCC don’t [have their bone metastases show up on] PET scans. There are a couple patients I’ve seen that it does show up in, and then it can be helpful to follow them. But people who were presenting de novo were often not getting a PET scan, and it’s honestly hard sometimes to get it paid for. So that can be difficult because it’s not one of the imaging [scans] that are recommended in the NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines.1

How should a patient like this be treated in accordance with the guidelines?

As far as the NCCN guidelines, frontline therapy says either sorafenib [Nexavar], lenvatinib [Lenvima], or atezolizumab [Tecentriq] and bevacizumab [Avastin]. They’re all category 1 recommendations.

Sorafenib is listed for Child-Pugh B7 cirrhosis as a category 2B recommendation related to some safety and small outcomes data in Child-Pugh B cirrhosis. Nivolumab [Opdivo] is still listed as a category 2B. I use it on rare occasions as frontline in patients who can’t get a TKI [tyrosine kinase inhibitor] or bevacizumab. Then FOLFOX [folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin] is still listed, although I think that that’s archaic and should probably be taken off the NCCN guidelines, but that’s just my opinion.

Do you think about the oral therapies in terms of dose adjustment to be able to maintain tolerability?

I think that’s important, to be able to dose adjust and to be able to get the patient to tolerate as much as you can.

Really the question is, when you’re thinking about the factors, do you change what you’re choosing based on age, gender, etiology—viral hepatitis? There have been some data that show that sorafenib might work better in patients with underlying hepatitis C.

How has coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) affected your treatment of patients?

I’ve had a couple patients who received diagnoses right before COVID-19 hit and then disappeared because they were scared of COVID-19, and now they’re starting to come back with really advanced disease and decomposition.

What I’ve been also noticing and what I’m worrying about are the patients who were getting their HCC screening and they haven’t been diagnosed yet, but now they’re not getting their screening. Everything got canceled, it never got rescheduled, and I’m worried in the next year or 2 we’re going to see a huge surge in advanced HCC cases when people develop symptomatic disease and they’re coming in and their screening was missed.

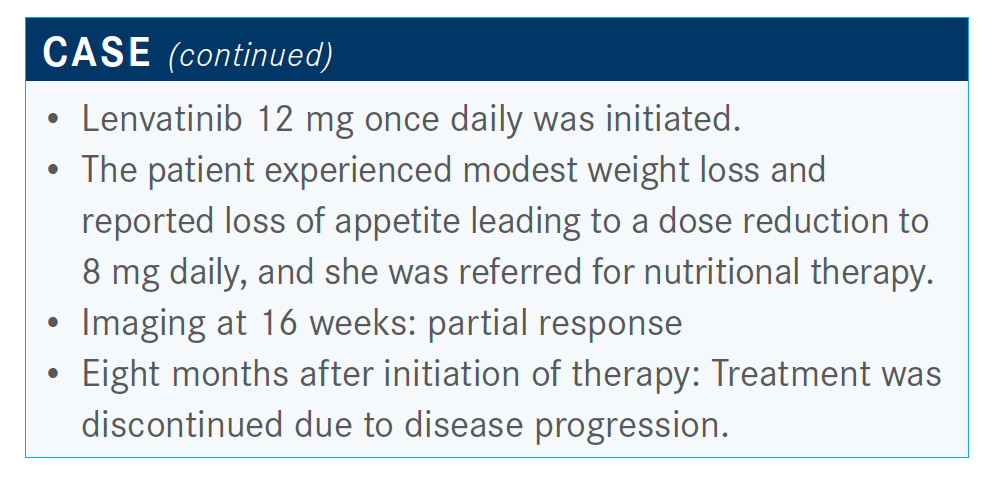

What are the dosing levels for patients receiving lenvatinib?

Over 60 kg is 12 mg and then under 60 kg is 8 mg. I will often start at a lower dose in people I’m worried about. She’s 77 years old. If she looked at all frail, I would maybe even start her 1 dose reduction down and ramp up, similar to how we were dosing sorafenib in the old days where we started low and then ramped up, as opposed to starting full dose and ramping down. With the TKIs, it can sometimes be difficult to decide and figure out what’s the right thing to do. There are clear data that Asian patients don’t tolerate as high of a dose, and we think that’s related to their [cytochrome P450] system—different genetics where they metabolize drugs differently. They often need lower doses than what they would be on based on their weight. So, some of those patients I’ll also start low and ramp up, as opposed to starting full dose and ramping down.

There are some studies that are starting specifically to look [if] that makes a difference in terms of tolerability, which we think it does. But does it affect survival? We know that in the colorectal [population], the survival is equivalent, but we don’t know that in HCC, so that will be interesting data to get to.

How has the HCC setting evolved over the years? Which trials were practice changing?

The SHARP trial [NCT00105443] really changed liver cancer treatment forever, where before this we had very little in terms of systemic therapy in patients with advanced HCC. We would have almost nothing to offer them.

They randomized patients who were treatment naive to either 400 mg twice daily or placebo.2 Now, the difference on the SHARP trial when you’re looking backwards, the primary outcome was time to symptomatic progression, and a secondary end point was time to radiologic progression. This is different from all of the studies that we have now where we’re looking more at time to radiologic progression. The other thing with this study is that patients continued on sorafenib through radiographic progression to get to symptomatic progression. And it was thought that that made a difference in terms of showing survival improvement.

It did improve overall survival, 10.7 months for sorafenib and 7.9 months with placebo, with a hazard ratio of 0.69 [P <.001]. I’ll point out that hazard ratio because this has been similar with most of the systemic treatment HCC trials that we’ve had. There was no difference in time to symptomatic progression, but there was an improvement in time to radiographic progression, 5.5 months with sorafenib versus 2.8 months with placebo. That was all we had for 10-plus years for HCC.

What are some newer data for this population?

The REFLECT trial [NCT01761266] was an open-label, multicenter, noninferiority trial. This was a statistical plan where they said, “We’re going to study these 2 drugs, but we don’t want to show that the lenvatinib is superior to sorafenib.” They wanted to show that it was noninferior. This was an important point because if this trial had been powered as a superiority trial, it would have been a failed trial. As it was, they were very successful.

It evaluated almost 1000 patients. They had to have no prior systemic treatment, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer [BCLC] stage B or C—B is multinodular HCC. In BCLC-C, you have vascular invasion or metastatic disease. So, they were treating patients before they got to vascular invasion or metastatic disease.

They excluded patients with over 50% liver occupation, bile duct invasion, or main portal vein invasion. That’s one of the December 2020 | Case-Based Peer Perspectives Spotlight 65 criticisms of the trial, that they excluded main portal vein invasion. They didn’t do this because of safety concerns. The reason that they did this was because they were also running the trial in Japan, and in Japan, sorafenib, on the guidelines, is not approved for main portal vein invasion, interestingly.

They stratified by region, Asia-Pacific versus Western; whether there was macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic spread; if their performance status was 0 versus 1; and body weight of less than 60 kg or over 60 kg, and then patients were randomized 1:1 lenvatinib versus sorafenib.

Lenvatinib was 8 mg for body weight of less than 60 kg and 12 mg for body weight of over 60 kg. The primary end point was overall survival [OS], and then they had a bunch of secondary end points including progression-free survival [PFS], time to progression [TTP], overall response rate, quality of life, and then they had some pharmacokinetic exposures.

Can you describe the efficacy seen in the REFLECT study?

This trial met the noninferiority end point. The median OS with lenvatinib was 13.6 months and for sorafenib it was 12.3 months [HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.79-1.06]. Now, you’ll notice that OS was longer than what we saw in SHARP. As our trials have been going on, our OS with sorafenib as frontline therapy has been getting a little longer; I think this is because we’re getting better at dose management of sorafenib, as well as supportive care for these patients with advanced cirrhosis and advanced HCC.

The key secondary end points were PFS and TTP, and lenvatinib was superior to sorafenib with both of these end points. The PFS for lenvatinib was 7.4 months and sorafenib was 3.7 months [HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.57-0.77; P <.0001]. TTP was 8.9 months for lenvatinib and 3.7 for sorafenib [HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.53-0.73; P <.0001]. Both of those hazard ratios were in the 0.6 range. There also was a much better response rate with lenvatinib, and now with the advent of immunotherapies, response rates have been talked about for many of these trials. We didn’t talk much about [responses] with sorafenib because sorafenib didn’t have much of a response rate. The response rate with sorafenib in this trial was 9%, with lenvatinib it was 24%. That’s about the range, if not better, than what we’re seeing with immunotherapy trials also. That’s really why lenvatinib became a new primary frontline option for our patients with advanced HCC.

What were the adverse events (AEs) seen in patients on this trial?

The toxicity profiles differ…managing AEs is one of the key things that we have to be good at to keep people on therapy and maintain their quality of life. This is something that I’ve been talking and teaching people about for over 10 years. The AEs that we see—we know with sorafenib that we see a fair amount of handfoot-skin reaction, 52% any grade, with 11% grade 3 or more, whereas with lenvatinib it’s much lower, 27% any grade, 3% for grade 3 or above. Diarrhea was about the same for both of the TKIs. Any grade hypertension was much more common with lenvatinib, 42% versus 30%, and then grade 3 hypertension was 23% versus 14%, respectively. So that’s 1 thing that we have to watch for. The reason for that is because lenvatinib has more of a VEGF effect than sorafenib does. Appetite loss was about the same, maybe a bit more with lenvatinib, and weight loss was a bit more with lenvatinib also.

How do you advise patients in regard to managing the AEs with lenvatinib?

Usually what I do is make sure the patient has a blood pressure cuff, and a lot of times they’ll get a blood pressure cuff when they get the starter pack sent to them. I have them check their blood pressure every day, and then I ask them to call in or send it in the patient portal once a week to monitor their blood pressure.

I usually start with a calcium channel blocker like amlodipine. I max that out. The next thing I add is a β-blocker, and I usually try to do carvedilol; the reason I choose carvedilol is because that has both alpha and beta, and so you also have benefits where it decreases portal hypertension as well. We think about nonselective β-blockers for variceal treatments and we usually think about propranolol or nadolol, but there are data for carvedilol with varices as well. And so that’s a good one to use for these patients with underlying cirrhosis and portal hypertension. We don’t often use carvedilol for varices because it has such an antihypertensive effect, and many of these patients with liver disease already run their blood pressures a bit low.

I usually reserve the angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for my third line because it does have an effect on renal perfusion. The patients with underlying cirrhosis are already at risk for developing ascites and volume overload, as well as renal insufficiencies, etc. So, I worry about giving them an ACE inhibitor that could potentially worsen that. I’ve seen ACE inhibitors, not necessarily in patients with cancer, tip people into ascites that they weren’t already getting. So that’s why I do it in that particular order. I find that generally if I get them past 3 antihypertensives, at that point I’m dose reducing and I’m getting cardiology involved. I’m comfortable up to 3 antihypertensives.

The other thing I will say, if you look at the lenvatinib package insert, it says if they’re above a certain number, then hold lenvatinib and get their blood pressure controlled. But I worry about that because I’m like, well, if I’m holding the drug that’s giving them hypertension but I’m also giving them antihypertensives, what if I drop them too low? Because I don’t want to stop the drug that’s causing the problem that I’m trying to fix. I haven’t gotten to that problem yet, but I worry about it.

What were some other results in REFLECT?

The treatment duration for lenvatinib was longer, 5.7 months versus sorafenib at 3.7 months. But there was a bit more discontinuation for AEs at 13% versus 9%, respectively. Second-line therapy was a bit more with sorafenib at 39% [vs 33%].

Overall, with this study, what they showed was lenvatinib was noninferior to sorafenib for OS, but it had statistically significant improvements in PFS, TTP, and response rate in the first line.

Would you use this regimen for patients with Child-Pugh B?

The other AE we saw was hepatic encephalopathy with lenvatinib more than we saw with sorafenib, percentagewise. There have not yet been safety data and efficacy data for lenvatinib for patients with Child-Pugh B, but they are coming. It’s hard to do studies in these patients because they have that competing risk of death from their cirrhosis, so it’s hard to show that they’re having a response and survival benefit from the drug while they’re also potentially getting sick and dying from their liver disease.

In general, what we see with any of the TKIs with Child-Pugh B is that they have to be dosed low. For instance, sorafenib with Child-Pugh B, their median daily dose was less than 400 mg, and few patients got above 400 mg.

I have used lenvatinib completely off label at this point. I have used it in Child-Pugh B patients, but I use it in the [patients who] have good performance status whose [disease doesn’t look as bad as] Child-Pugh B [usually] looks. I’m particular about those patients. I start very low; I’ll start them at 4 mg once a day or maybe even 4 mg every other day, and then I see them in the office every 1 to 2 weeks and closely monitor labs and adjust their dose until I can get them on a stable dose. I warn them about early encephalopathy, ascites, and [other possible AEs]. It is difficult but it’s possible. It just takes a lot of work. But, in the sorafenib data, we did see a survival benefit in patients with Child B cirrhosis if you can get them on therapy and keep them on therapy.

In my mind, it depends on what the reason [for the Child-Pugh B diagnosis] is. Patients whose albumin is really low, like 2 [g/dL], I worry a lot about, and a lot of them I’ll work hard on nutrition for a while. For a lot of them, the albumin is low because of nutrition, but if they’re already not eating, well, then that’s usually a bad sign.

If they have Child-Pugh B because their bilirubin level is 3 [mg/dL], I worry much less. TKIs will make their bilirubin level go up. It interferes with the transport enzyme and metabolism, and the bilirubin will go up by a point or 2 usually in patients who are on the border, so I worry [less]. I’ve seen their bilirubin level go up to 6 or 7 [mg/dL] and kept treating because they’re feeling fine otherwise. OK, great, I’m fine with that. But, if they have Child-Pugh B7 because of albumin, I worry. If it’s B7 because of ascites or encephalopathy, to me it depends on how controlled they are now, and if I think I can make any medication management changes to get them more controlled. For instance, if they’re a B8 because [of] their ascites, it is not great, but they’re not on diuretics and nobody told them to be on a low-sodium diet, I can fix that. I can change that Child-Pugh B8 to a Child-Pugh A6 with a bit of dietary and diuretic changes. That’s how I think about Child-Pugh B in general.

Were there any other toxicities usually seen with TKIs that you haven’t discussed yet?

Fatigue…in the study, it was equivalent between sorafenib and lenvatinib. It was about 45% to 50% with both of the TKIs, and it is definitely a problem. The 1 thing I like with lenvatinib and the fatigue is that because it’s once a day, if a patient is having a lot of fatigue, I change it and tell them to take it at night instead of in the morning. I find that that can help some. That’s a little harder with sorafenib as a twice-a-day drug.

I also [think] coffee is good for the liver. There are clear data in the liver literature that if you have a patient with a cirrhotic [liver], and they drink coffee—2 cups a day minimum—it decreases the risk of liver cancer by half. It’s now in the European guidelines that every patient with chronic liver disease should be recommended to drink coffee every day. Americans have not caught up to Europe yet [in that regard]. It also decreases the development of fibrosis in fatty liver, alcoholic liver disease, and hepatitis C. For some reason our livers like coffee, and it’s a dose response curve. So, the more you drink, the more benefit you get. So, if somebody is having fatigue, I encourage them to drink coffee because that also helps because of the caffeine. That’s something I do a lot.

I talk to them about planning around their fatigue. If they’re having more fatigue in the morning, then delay things until later in the day. I have patients that I’ll let dose reduce if they have an event or something like that. “OK, it’s your granddaughter’s birthday party on Saturday. Why don’t you dose reduce that day or the day before for a few days?” That’s OK to do it to be able to maintain their quality of life.

I [also] find that the skin issues and the diarrhea tend to settle down. Especially if they’re getting diffuse skin rashes, you can definitely treat through that and it will settle down after a few months, usually. I find that hand-foot-skin reaction tends to get less painful, and the fatigue tends to worsen [because] it wears on them.

References:

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hepatobiliary cancers, version 5.2020. Accessed November 13, 2020. https://bit.ly/2YGXWlA

2. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378-390. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708857