Vogelzang Discusses Treatment Choices for mCRPC in the Frontline and Beyond

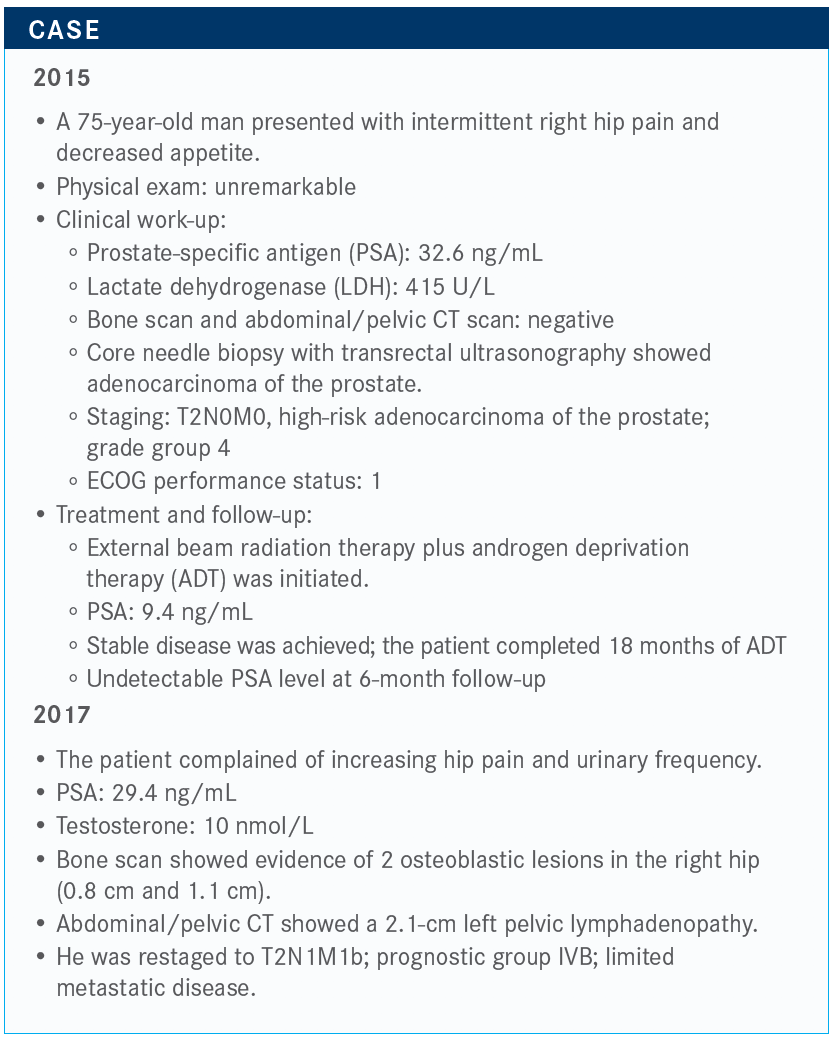

During a virtual Case Based Peer Perspectives event, Nicholas J. Vogelzang, MD, reviewed the case of a 75-year-old man diagnosed with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Nicholas J. Vogelzang, MD

During a virtual Case Based Peer Perspectives event, Nicholas J. Vogelzang, MD, medical oncologist, Comprehensive Cancer Centers, associate chair, Genitourinary (GU) Committee for US, Oncology Research, vice chair of GU Committee SWOG, and clinical professor of Medicine, University of Nevada School of Medicine, Las Vegas, NV, reviewed the case of a 75-year-old man diagnosed with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) and the therapeutic options in the first-line setting.

Targeted Oncology™: Does anything in this case stand out to you?

VOGELZANG: Given that he probably had bone metastases at diagnosis, I’m not surprised that the bone scan was negative. The bone scan is not that accurate, and many times we either do the MRI or we do a prostate-specifi c membrane antigen PET scan.

He is older and has hypogonadism, so you would want to prevent insufficiency fractures. I would probably add at least Prolia [denosumab] once every 6 months. Whether I would add Zometa [zoledronic acid] every 3 months is arguable, but I would at least get him on Prolia to start and make sure we don’t get him any further down the osteoporotic path.

What are your thoughts on these answers for the therapeutic options in the metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) setting?

You could argue that you could begin docetaxel, enzalutamide [Xtandi], sipuleucel-T [Provenge], or other options such as apalutamide [Erleada]. Maybe you would not begin [new treatment]; maybe you would not continue Lupron [leuprorelin]. Maybe you would just monitor the testosterone.

The majority would either use abiraterone [Zytiga] or enzalutamide. Nobody would use chemotherapy, particularly in this older man, and no one would use sipuleucel-T yet. I think that’s fair. I’m not a big fan of giving enzalutamide in [older] patients, primarily because of the central nervous system fatigue events. But, on the other hand, at age 75 he might have some fluid overload or other issues that occur with abiraterone. It’s an even split, and it makes sense to me that we would do that.

How do you choose between chemotherapy and androgen receptor (AR)–targeted therapy?

The NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines show the preferred regimens are abiraterone, docetaxel, enzalutamide, or sipuleucel-T, and under some circumstances radium-223 [Xofi go].1 I don’t know anyone who uses mitoxantrone [Novantrone] anymore. I took that off the formulary. I’ve never used Abraxane [nab-paclitaxel] or fi ne-particle abiraterone, which is just another type of abiraterone.

Under what circumstances would you use docetaxel is a more likely question. Given this patient’s age, I think nobody would push to give docetaxel.

When do you use docetaxel for your patients?

I use it early. For a patient like this with not a lot of bone disease and node only, [in England] they would give docetaxel early and watch the patient, particularly if they got the PSA down. But it’s not a standard approach in the United States. I don’t hesitate when using docetaxel; it’s a good drug. In the [older] population you have problems, nonetheless.

I think most of us use docetaxel in younger patients. What I often do is, for patients with hormone-sensitive disease, I’ll give docetaxel in 6 cycles and then follow up with abiraterone or enzalutamide as maintenance. The typical approach in the United States is Lupron and abiraterone or Lupron and enzalutamide. Docetaxel isn’t widely used here, although it’s cost effective and used widely in England.

How would you proceed now?

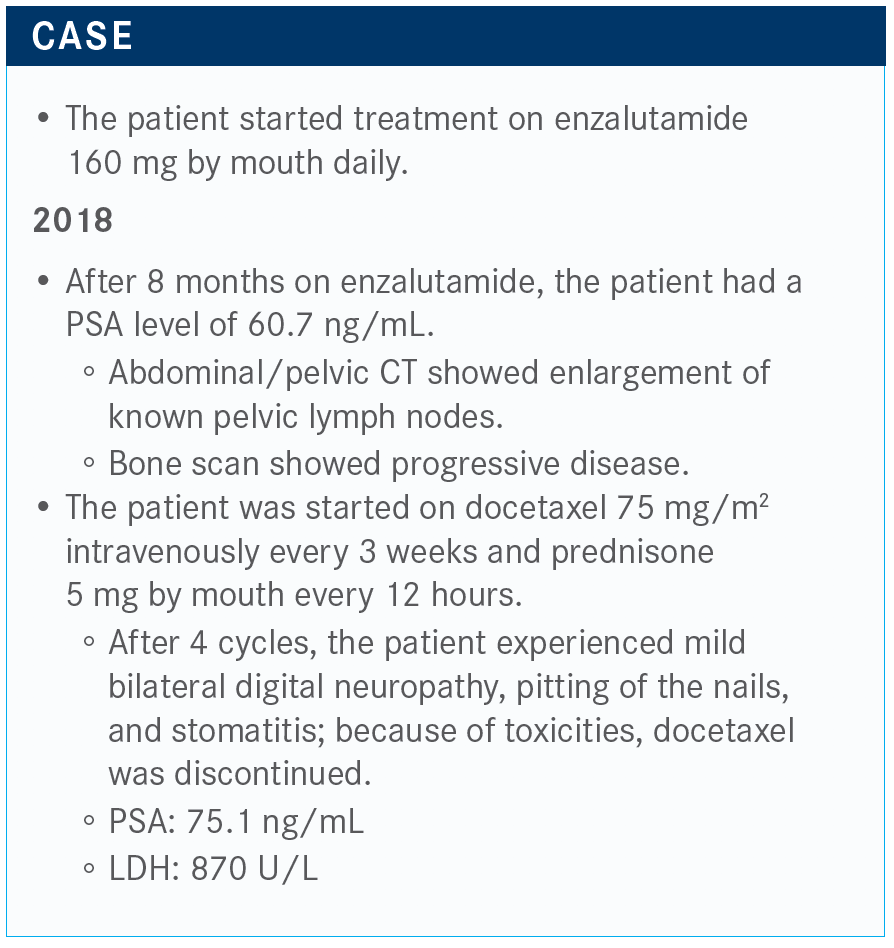

There was involvement of his rib, and that’s a typical thing for prostate cancer. It grows in the marrow. Then he is started on docetaxel, and after only 4 cycles he gets some of the typical adverse eff ects [AEs], namely neuropathy, nail changes, stomatitis, and he doesn’t want to keep going. But now, his LDH is going up and his PSA is up to 75 ng/mL.

You could add abiraterone, cabazitaxel [Jevtana], or you could switch to radium-223. We could test for DNA repair deficiency if he has a BRCA mutation. You could also consider sipuleucel-T. But now his PSA is high and he’s having pain, so sipuleucel-T falls off the table.

Would you give cabazitaxel to a patient who did not tolerate docetaxel?

In the past, [patients received] 25 mg/m2 of cabazitaxel. I give 20 mg/m2. I just gave it to a 93-year-old patient. It is well tolerated at the lower dose, not as well at the 25 mg/m2 dose.

The most recent data [on cabazitaxel] was from Ron De Wit, MD, in Rotterdam, a study called CARD [NCT02485691].2 It was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. It was a randomized trial of men who had had both taxane and a prior AR-targeting agent within 12 months, either abiraterone or enzalutamide. Then they were randomized to cabazitaxel at 25mg/m2 versus abiraterone or enzalutamide.

It was not a gigantic study, with about 130 patients per arm. The primary end point was radiographic progression-free survival [rPFS], and the secondary end point was overall survival. I noticed that the cabazitaxel was [dosed at] 25 mg/m2, and that was with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. That’s a harsher regimen than we would normally expect in the United States. The study was designed before the label on cabazitaxel was changed.

A [large portion] of the men had pain, about 70% or so. The split between abiraterone and enzalutamide was about 50/50. The median PSA number was high. It was in the 100 range, so fairly advanced disease that we would come to expect by the time you’re in cabazitaxel territory.

What was the efficacy of cabazitaxel in this study?

The CARD trial met its primary end point. The rPFS was significant, with a P value at .001, and a median of 8 months for cabazitaxel versus 3.7 months for AR-targeted therapy [HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.40-0.73]. The 3.7 months is typical for second-line abiraterone or enzalutamide. There’s a small number of patients who respond. Most of them would be the enzalutamide patients, but this is doubling of rPFS.

The overall survival, which was the secondary end point, was also met with a hazard ratio of 0.64. That’s better than most clinical trials nowadays. Most clinical trials come in at between 0.70 and 0.75, so this one is impressive. The median survival was 13.6 months compared with 11 months for cabazitaxel and abiraterone or enzalutamide, respectively [P =.008]. Even though crossover was allowed, there was still a survival advantage.

The clinical PFS, which includes death or symptomatic progression, had a hazard ratio of 0.52, with a median PFS of 4.4 versus 2.7 months, respectively [P <.001].

This study helped me firm up my opinion about cabazitaxel. It hit on all the end points. It hit on PSA response, with 35.7% confirmed response with cabazitaxel versus 13.5% with abiraterone or enzalutamide.

It hit on tumor response rate, with 36.5% versus 11.5%, respectively. It hit on pain response, with 45.0% versus 19.3%. I don’t see a lot of negatives except for the toxicity.

Would you describe the AEs that come with this treatment?

The rate of any-grade AE was similar in the cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzalutamide group. Serious AEs were also similar. AEs leading to treatment discontinuation were higher— double in the cabazitaxel group—but AEs leading to death were more in the abiraterone or enzalutamide group, probably because of tumor growth but it’s always hard to know. That is a good safety profile.

There was a higher quality of life in the cabazitaxel arm, and the general downward trend at the end of life was not accelerated by cabazitaxel. For the first cycle through the sixth cycle, cabazitaxel had a better pain [reduction] and less concerns about PSA.

What is your personal experience with cabazitaxel?

I have had some long-term responses to cabazitaxel. One patient has had [more than] 30 doses. As long as they don’t get bladder bleeding or unmanageable diarrhea, they usually don’t get neuropathy with cabazitaxel—sometimes but not usually. It’s a reasonable drug for this [older] population.

References

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Prostate cancer, version 2.2020. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://bit.ly/30gVbHR

2. de Wit R, de Bono J, Sternberg CN, et al; CARD Investigators. Cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2506-2518. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911206

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More