Roundtable Discussion: Salit Explores Use of Steroids and Therapy for Acute GVHD

During a Targeted Oncology case-based roundtable event, Rachel B. Salit, MD, discussed the case of a patient with acute graft versus host disease, steroid dependence, and therapy for steroid-refractory disease.

Rachel B. Salit, MD

Associate Professor

Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

Associate Professor

University of Washington School of Medicine

SALIT: First I would like to hear from the people who are at transplant centers. What do you use for your standard prophylaxis for transplant in the [myeloablative] or reduced-intensity setting?

MEI: Historically we use a lot of tacrolimus or sirolimus [Rapamune]. I have used [those] a lot. Part of it is because of how much TBI [total body irradiation] we’ve used, and we still use TBI even for acute myeloid leukemia. So we like tacrolimus or sirolimus because they result in less severe acute GVHD and very rapid [engraftment].

SALIT: So no MMF [mycophenolate mofetil] or methotrexate?

MEI: Over the past couple years, if there was a mismatch, we would just do [posttransplant cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan)]. But historically, we would add low-dose methotrexate if there was a micro mismatch rather than doing ATG [antithymocyte globulin]. But I have been leaning more and more on the posttransplant side. So tacrolimus or sirolimus have just been long-standing [choices].

SALIT: For the risk factors for development of GVHD, there’s donor and recipient factors. The first thing we look at when we look for a donor for patients is whether their human leukocyte antigen [is a] match.

We know there’s a 25% chance that the siblings will be a match. Then we do an unrelated donor search through registry to see if there is a donor match. Historically we looked at a 10-out-of-10 match. So we looked at A, B, C, DR, and DQ. And more recently, we’re starting to use DP also as a locus, so a 12-out-of-12 match. In some cases, DP [mismatch] has been shown to confer worse GVHD.

We also look at gender matching, but we look more for male donors even in female recipients because of the donor parody. If you have a donor who has had multiple children, they will have antibodies against the mismatch for that child and that confers a higher risk for GVHD.

Older donor age and CMV-positive donors confer the higher risk of GVHD. ABO blood type has been controversial. [Some studies show] it has a higher risk for GVHD if they are mismatched, and some have shown that is not true.

As far as stem cell source, we use almost exclusively peripheral blood. I’m sure you’ll see some patients with aplastic anemia that are coming through with bone marrow. At our center, we use probably 80% peripheral blood transplants. There was a study comparing peripheral blood to bone marrow that showed bone marrow had [less risk of] chronic GVHD, which has not translated into clinically using more bone marrow.1 For conditioning intensity, the higher it is, the higher the risk for acute GVHD.

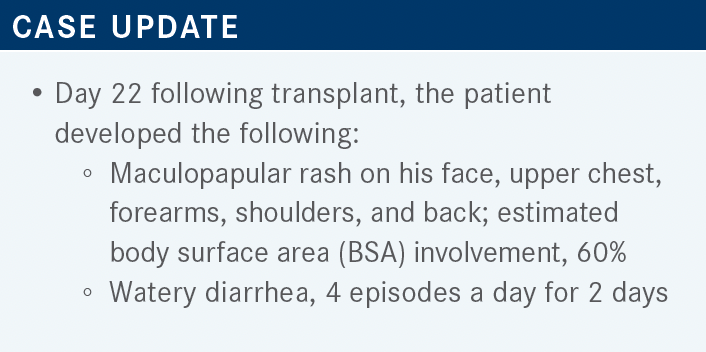

SALIT: For those seeing patients in the clinic after they come back from their transplant, you can look at pictures [showing percentage of involvement] for each arm, leg, and torso. That’s how we calculate the BSA involvement, and [more than] 50% is stage 3. There is also staging of GVHD using episodes and volume of diarrhea per day. The third item [for staging] is the bilirubin from the liver function tests.2

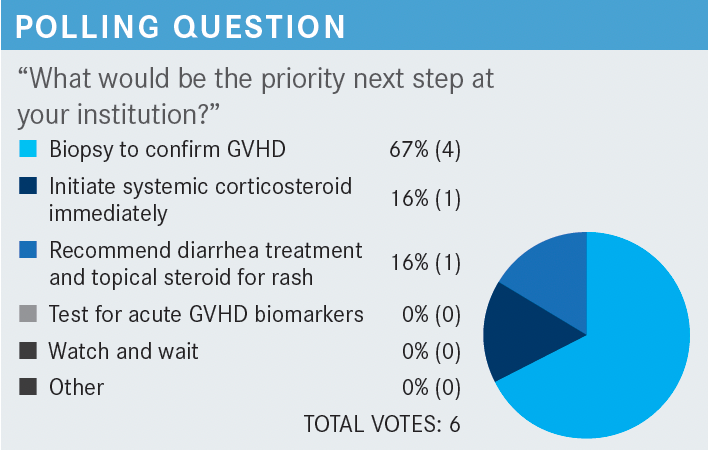

YAN: I voted to have a biopsy to confirm GVHD.

SALIT: Someone else said recommend diarrhea treatment and topical steroid for rash, and I said start systemic steroid therapy. I think that a couple of things could be true. I think 60% BSA is a lot to treat topically. We do not routinely test for acute GVHD biomarkers. So I would say it’s probably somewhere between doing a biopsy to confirm GVHD and initiating systemic steroid therapy immediately. If it was just the diarrhea and not the rash, I would biopsy to confirm GVHD.

In a patient with diarrhea 4 times a day, one wonders if it’s infectious diarrhea or CMV. You don’t necessarily want to treat them with empiric steroids if it’s something that’s not GVHD. I don’t know if your GI [gastrointestinal] physicians are the same as ours, but a lot of them, if you start the therapy, won’t do the biopsy.

MEI: What dose of steroids would you do?

SALIT: I would probably do 1 mg/kg for this person. I think it’s hard to treat GVHD with less than that. If it’s only the upper GI tract, we sometimes try to do 0.5 mg/kg, but I would do 1 mg/kg for this person. It’s difficult in patients with rashes, especially if they are symptomatic, to wait for biopsy results before treating them.

But I don’t think it’s wrong to do the biopsy. If in your office you can biopsy the skin or have good access to a GI doctor, I think you can biopsy them. I guess then the question is, do you wait for the biopsy to come back before you empirically treat them? I will say probably not if they have 60% BSA area involved. At that point, pull the trigger and start the steroids.

I’m wearing my long-term follow-up clinic hat because I just came out of working at [that] clinic for 1 month. If you have this patient and halfway through the tacrolimus taper, [this happens] and you wonder whether to put the tacrolimus, cyclosporin, or sirolimus back up to therapeutic doses or just start steroids, I usually recommend reinitiating the steroid-sparing agent at the therapeutic dose. I think it cuts back on the duration and the quantity of steroids that you will need.

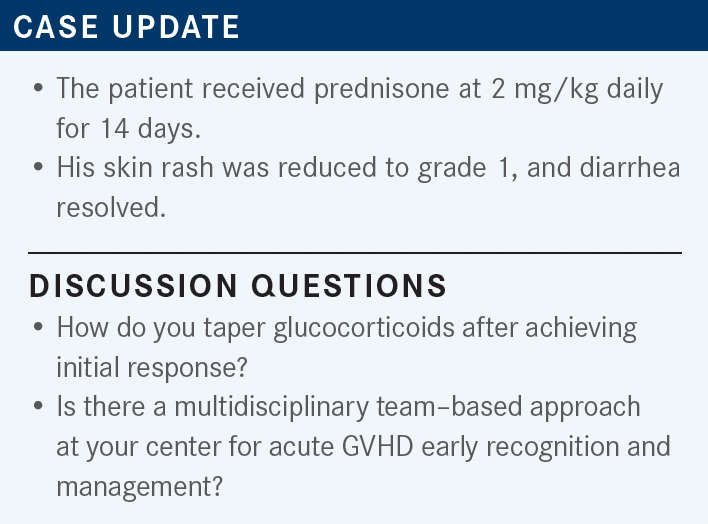

ARORA: It’s a gradual taper. I think the long-term follow-up care have guidelines of how to taper while monitoring the symptoms.

SALIT: We usually recommend tapering by 10% every 5 to 7 days. So if the patient was started on 1 mg/kg and they successfully resolved, then we would taper by 10%, depending on how early on. If it was acute GVHD, they would be tapered every 3 to 5 days, but if it was delayed acute GVHD, we would usually taper every 5 to 7 days by 10%.

MEI: [At my center], we have a mailing list. For any patient that we suspect has acute GVHD for whom we are considering instituting systemic corticosteroids, their names go on a list that goes to a few of the transplant physicians and the pharmacy team. It’s because we typically have some clinical trial open, like the MAGIC, so we try to get some patients in for trials and talk over their case. In fact, if you don’t email that list and anyone starts systemic steroids, the pharmacist gets notified and then they send an email to the group to discuss what to do next. Some trials you need [to screen patients] within 3 days of steroids, so that’s why we do this—to get patients screened. It’s always Friday afternoon that you can get started on steroids because you need to have something planned for Monday.

SALIT: We do not have anything as coordinated in place. I would say if someone developed acute GVHD, we usually just treat them. The person attending in the long-term follow-up clinic sometimes gets notified if someone needs assistance in management, but otherwise I don’t think we have a multidisciplinary team–based approach to be honest. If it’s GI or skin, we’ll get dermatology or GI involved, but there isn’t a real multidisciplinary-based approach.

MEI: What’s your threshold for admitting for IV [intravenous] steroids? If there’s 50% to 60% BSA, we can do without; but if it’s the whole body, we sometimes admit for IV steroids.

SALIT: I would say for skin I almost never admit. My threshold for admission is almost exclusively for deep GI, if there is dehydration, or people can’t keep up with fluids and electrolytes.

MEI: We have admitted a decent amount of patients if the rash is almost all the BSA. Our culture has often been to admit and give IV steroids, but I think that’s institution dependent.

SALIT: Ironically, you bring up an interesting point. Our thinking is that skin GVHD is not as bad as GI, so we treat it less. But with skin GVHD, response is not as good as GI after just starting a steroid at 1 mg/kg, and it seems there are more refractory patients. GI GVHD is scarier because the patients are getting dehydrated and losing electrolytes and because...we tend to admit for IV because one is worried if they are absorbing drugs, especially when they’re on things like sirolimus [or ruxolitinib (Jakafi)], which can’t be given IV. It’s really difficult to manage them as outpatients.

In general, we probably overestimate how well patients respond to steroids. If you look at a lot of the data, about 70% of patients respond to steroids, which is shocking to me that 30% of patients are steroid refractory and another group is steroid dependent. Meaning, if you put them on steroids, you can’t taper the steroids without them flaring. We previously did not have a good steroid-sparing agent that allowed us to taper the steroids. We had patients on 2 mg/kg for weeks waiting for the diarrhea to stop, and every time we tried to taper, they would flare up again.

MEI: When do you consider someone refractory? Is it different if it’s skin vs GI?

SALIT: So that’s a good question. Usually, if they’re 1 week on 2 mg/kg, they’re refractory.

MEI: I was always taught that it takes longer for the GI tract to heal, so you give steroids a little longer, maybe up to 2 weeks. Although usually you see something happening by 1 week. I feel like for skin, there’s a lower threshold to throw in something else. We’ve always tended to give [monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)] relatively early if the rashes are bad stage 3 or 4 skin GVHD, and it’s not turning around within a few days.

SALIT: I did my training at NIH [National Institutes of Health], and we [limited the intake of food]. When I came to [University of Washington], they thought I was crazy because the training now is that, for the patients with GI GVHD, it’s better to feed the gut. So it’s hard to make the diarrhea disappear vs when we used to fast people, and the diarrhea would disappear on that first week on steroids and then we could taper. So I don’t know. I still believe in gut rest, but I think that’s because that was the way I was trained. Gut rest results in less diarrhea and being able to taper the steroids faster.

MEI: This is a fine line. We’ve seen patients with the worst GI GVHD [who] take a pill, and it’s in the stool 30 minutes later. I’ve done a lot of gut rest when it’s bad, and we’ll try to feed them a bland diet when it’s not so bad. But I don’t know where the dividing line is. I’ve probably trained somewhere in the middle in terms of the cultures.

SALIT: Almost everyone said they would reach for ruxolitinib first. Because it’s oral, if patients come with delayed acute GVHD [that] doesn’t respond to steroids, it’s an easy drug to use. I would say, photopheresis, sirolimus, and mAbs are still viable options, [and] in patients that are cytopenic, photopheresis. We still use a lot of photopheresis to be honest, and especially in patients who can’t take oral so it’s hard to give ruxolitinib and sirolimus. ATG, I would say, has completely fallen out of favor in terms of treating acute steroid-refractory GVHD.

The big picture summary [for acute GVHD] is that patients who get high-intensity transplants, mismatched transplants, and peripheral blood transplants are at higher risk. Some things that we’ve done to ameliorate this is using posttransplant cyclophosphamide, ATG, or other T-cell depleting mechanisms.

The concern when you do this is that you have increased [likeliness of] relapse in the patient. So you are always going to have a trade-off between GVHD and relapse. I don’t know if we found anything yet to guarantee that the patient doesn’t get GVHD and doesn’t relapse. We know that there’s some association between GVHD and not relapsing.

We still know steroids are No. 1. I wouldn’t say ruxolitinib has taken the place of steroids [because] we’re not using it as first-line therapy, but we have ruxolitinib as a second-line therapy, which is oral. And other than the cytopenia, [it] is fairly well tolerated.

ARORA: How many patients end up with acute GVHD?

SALIT: At our center, we have about a 60% to 70% rate of acute GVHD. Probably at least two-thirds of them are treated with systemic therapy. So it’s a large percentage.

At other centers, I’ve talked to people at City of Hope, it is quite a bit less. Maybe it’s because we just do a lot of upper GI scoping. So we see a lot of the stage IIA upper GI. We scope people early too. We also do a lot of mismatched transplants at our center still. So a lot of 9/10 matches. We still give a lot of methotrexate and do myeloablative transplants.

I think we do a lot of things that probably cause people to get GVHD. But our relapse rates are very low. So it is a trade-off between GVHD and relapse, but we see a large percentage of patients, more than 50%, with acute GVHD.

ARORA: Does cord blood make a difference?

SALIT: I would say somewhat. But cord blood is going to make more of a difference in the chronic GVHD setting than in the acute setting. We give a lot of high-dose TBI with our cord blood transplants. With kids it’s a little different because they’re getting single-cord transplants. Adults get double-cord transplants, and that confers a higher risk of acute GVHD.

But the cord blood transplants have very low chronic GVHD. With posttransplant cyclophosphamide following peripheral blood transplants, we still see a lot of acute GVHD. So the benefit has been with the chronic, not necessarily the acute. I think ATG is a little different because there is some benefit in acute GVHD as well.

MEI: So a majority of your patients with acute GVHD probably have grade 1 or 2, right? I feel like if they have nausea on day 19 or 20, we’ll usually wait it out. Maybe give them some nonabsorbable steroid and see how it goes.

SALIT: If they’re treated with beclomethasone [Qvar], it is still considered GVHD.

MEI: Sometimes it gets variably recorded as GVHD, and sometimes it doesn’t. So I think there’s some variability there with the data.

SALIT: Yes, it’s difficult. I have a GVHD prevention trial open now, and it’s very complicated. I’ve never had a GVHD prevention trial, and it’s shown me what people call GVHD can be very variable.

MEI: Yes, for sure. We have a [similar] trial in right now.

MITIN: If survival is 1 month for steroid-resistant GVHD, is that the progression-free survival from the disease? What is that 1 month? That is a horrible time frame for the patients with steroid-resistant GVHD.

SALIT: Steroid-resistant GVHD has a terrible prognosis. Twenty percent have a 6-month survival. So [for the phase 3 REACH2 trial (NCT02913261), the median failure-free survival was 1 month for the control arm vs 5 months for the ruxolitinib arm].3

I guess it’s not necessarily that they only survived 5 months vs 1 month, but it’s unclear to me if the failure was death or just progression and they were treated with something else. I don’t know. I agree with you. It’s confusing because this is failure-free survival.

MITIN: Are they talking about the initial disease during the steroid-resistant phase?

SALIT: Yes, once there is steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent GVHD and they start ruxolitinib or best-available therapy. How long did they live for? I don’t know. This is confusing because it’s treatment failure. But then it’s unclear if they failed that treatment, did they go onto [another] treatment? Maybe they did and survived. I don’t know. But yes, I think the 5 months vs 1 month is the failure-free survival. I would say third-line therapy is even more unsuccessful than second-line therapy.

REFERENCES

1. Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al; Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trial Network. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1487-1496. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa1203517

2. Harris AC, Young R, Devine S, et al. International, multicenter standardization of acute graft-versus-host disease clinical data collection: a report from the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(1):4-10. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.001

3. Zeiser R, von Bubnoff N, Butler J, et al; REACH2 Trial Group. Ruxolitinib for glucocorticoid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1800-1810. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917635