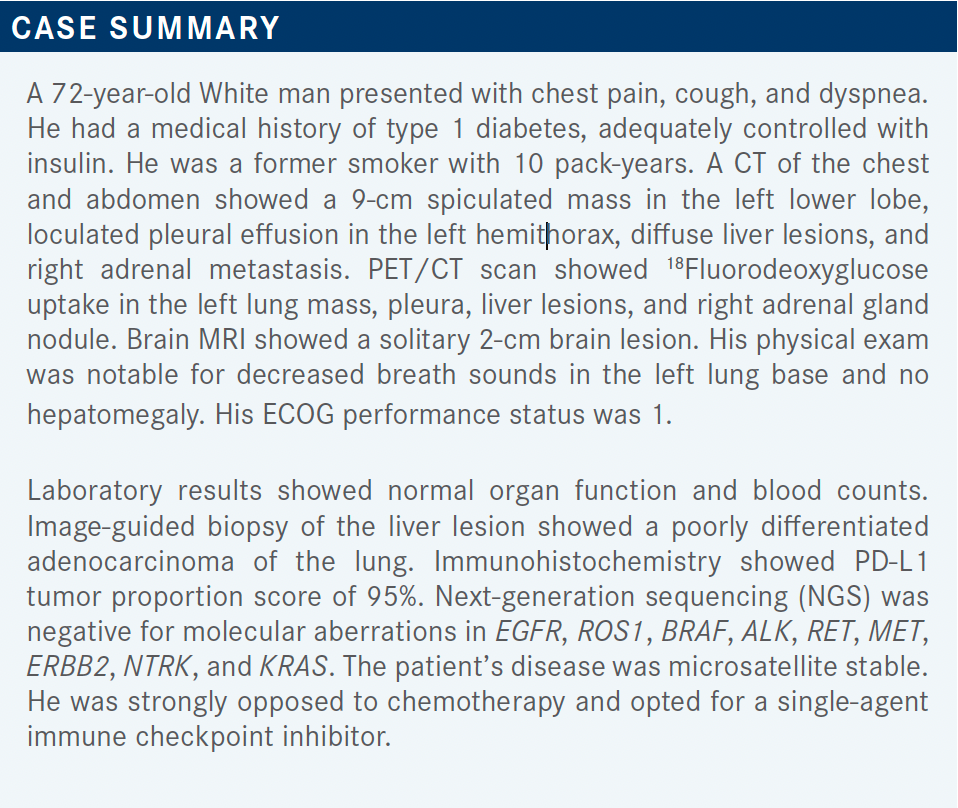

Roundtable Discussion: Practice Updates on Late-Stage Non–Driver-Mutated NSCLC

During a Targeted Oncology case-based roundtable event, David P. Carbone, MD, PhD, discussed molecular testing and treatment for a patient with late-stage non–small cell lung cancer.

David P. Carbone, MD, PhD

Professor of Internal Medicine

The Ohio State University

Director, James Thoracic Center

The OSU Comprehensive Cancer Center—The James

CARBONE: In the NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines and in practice, the first step when you’re dealing with non–small cell lung cancer [NSCLC], especially nonsquamous disease, is molecular testing. In my practice, we would get a core biopsy like the one described, and we would do a tissue-based analysis. At my institution, it’s all done in house, and we get EGFR, ALK, ROS1, RET, and MET [results] within 5 days and NGS [results] within 2 weeks for MET, BRAF, and those kinds of things.

We generally use liquid biopsies only to look for resistance alterations, if we get an outside referral with inadequate tissue, or [if it is an] uncommon situation of inadequate tissue locally.

KHASAWNEH: In my practice, we contract with a commercial lab, Integrated Oncology, for NGS, and it takes about 3 to 4 weeks. So when I see patients, my approach is a bit different because of the practice. I do both liquid and tissue biopsy, because to get the liquid faster, I can use FoundationOne liquid biopsy and send tissue for NGS, waiting for the molecular markers to come. Whichever comes first with the answers that I’m looking for, I will use to make decisions for the patients.

CARBONE: Yes, I think that’s a very reasonable approach. We usually use another platform, but we often get our results back within 4 or 5 days, which is remarkably fast and very easy.

TEJWANI: In our institution, the turnaround time in house is at least 2 weeks, so we’ll end up sending to FoundationOne or Tempus, but I wish the turnaround time was better. Five days is great.

CARBONE: That is a limiting factor with these patients.

TEJWANI: We are doing the PD-L1 and PD-1 markers in house.

CARBONE: Do both of you use a commercial platform, so you get the MET exon 14, BRAF mutations, NTRK, and all of those?

TEJWANI: Yes.

CARBONE: Anybody else have a different approach?

KUMAR: I’ve sent for a Tempus panel, so both solid and liquid. Usually, we have to wait for at least 2 weeks before we can even start any targeted therapy.

CARBONE: I think we all are faced with patients with a new diagnosis who want treatment to start right away, so that 2 weeks seems like forever. Do you ever have difficulty convincing patients to wait for their testing?

KUMAR: There are some patients who cannot wait, are symptomatic. I start with a chemotherapy combination, and when I get the NGS panel then, [if appropriate, I start] immunotherapy [IO].

CARBONE: [It’s interesting] to see that a lot of [you] are sending both liquid and tissue at the same time. It does seem like there’s a redundancy there. It’s like getting a brain MRI and a head CT at the same time.

KUMAR: No, [for us] Tempus doesn’t run the liquid unless there’s inadequate tissue. So we save some time.

AL BAGHDADI: We use FoundationOne when there’s sufficient tissue. It takes about 2.5 weeks to come back. We don’t do concomitant liquid biopsies unless the tissue was inadequate, and we wait. Our pathologist would rather stay away and not run any testing on these patients. They started out with doing EGFR and ALK testing, and as the number of these mutations increased, they stayed out of it. If the patient requires immediate treatment, where they can’t wait 2.5 weeks, I give 1 cycle of carboplatin- or cisplatin-based doublet treatment without immune checkpoint inhibition while waiting for the test results.

CARBONE: That’s a very logical approach. I think the biggest mistake is using an IO in someone that you then want to switch immediately to osimertinib [Tagrisso], because of the possible complications and lack of benefit of IO in that setting. Sometimes I can’t get a pembrolizumab [Keytruda] approval immediately, and I want to start right away, so I’ll start with the chemotherapy alone with cycle 1.

MAHAJAN: At Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, the [tissue biopsy] is done by the in-house pathologist, and they have expanded their lung panel— they’ve been checking both DNA- and RNA-based testing. That’s helpful because not only does it get done in house but it’s also part of the same pathology report. So you don’t have to log into different portals to get different results. The same report also has PD-L1 expression and microsatellite instability testing.

The problem, even in house, is the turnaround time, especially if you are in ambulatory setting or a satellite hospital. In those situations, sometimes you’re on your own; you may order a liquid biopsy with Guardant or something similar just for the timing. But [having] a more comprehensive report where everything is included really helps with patient care.

CARBONE: I agree. I’ve been working on trying to go 1 step further and having molecular reported just like any other laboratory tests in the EPIC system. I get messages and alerts in my inbox if I get a potassium [result] that’s 0.1 out of range. And yet, if I have a patient with an ALK fusion, I never get an alert in my inbox. We now have EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and RET in our EPIC system; all those things show up in the same laboratory panel as a complete blood count or a chemistry panel would. And we can just click on them to see which variant or whether it’s wild type. But still, it doesn’t alert me if it’s abnormal. I think EPIC is working toward a better integration of all the different molecular platforms, but I think it should be presented that way.

NEMUNAITIS: You’re saying if there is an EGFR mutation, they alert you that there was a mutation found?

CARBONE: EPIC shows it in the laboratory panel, but right now EPIC doesn’t alert me. But I’ve trained our molecular pathologist to page us if it comes back positive. So if we get a new EGFR result, I’ll get a page saying, “Jane Smith has an EGFR L858R.”

NEMUNAITIS: That’s great. I have patients with [immune thrombocytopenic purpura], and I get paged every month because [their result is] still low [after] 5 years, but I agree, that’s amazing.

CARBONE: The impact of potassium at 3.2 mmol/L is way less than that of an ALK fusion mutation in a newly diagnosed patient. So you would think that they would notify you.

CARBONE: How many of you would do SRS for an asymptomatic brain metastasis in this setting or try up-front therapy? Would you just treat with systemic therapy, or would you radiate for a 2-cm, asymptomatic brain metastasis?

KUMAR: I would stay with systemic therapy and still get the opinion from the radiation oncologist.

AL BAGHDADI: I would have the radiation oncologist see them, and probably use CyberKnife radiosurgery. At 2 cm—if it was smaller than that, I would start with systemic therapy for sure.

WINTER: [As a] radiation opinion, 2 cm is an interesting cutoff point for us. When we get above 2 cm, we usually have to go with a lower dose level. The control is not as good with SRS once you get above the 2-cm mark because you have to dose reduce. There are some strategies that you can use to address that, such as a staged approach, where you bring the patient back a month later and give a second dose. But if you can avoid having to do that, it’s definitely beneficial.

That being said, I recognize that a lot of the targeted agents and IO agents have intracranial efficacy. To the extent that we can avoid radiotherapy and only treat if needed, I’m all for that. I think it’s an individualized decision. In this patient I’d probably, with all else being equal, lean toward it just because of the size.

CARBONE: If [the patients] were symptomatic and required steroids, then that would be a reason for radiation, trying to get them off steroids before IO. Or if there were 25 metastases but [the patient was] still asymptomatic, you could do a trial of the IO therapy. I’ve seen very good central nervous system [CNS] responses to IO, but I’ve also seen a lot of CNS-only relapses with IO—systemic control, but CNS relapses. It’s unclear. But with the targeted therapies, I’ve seen durable long-term control with multiple brain metastases with no radiation with ALK or EGFR.

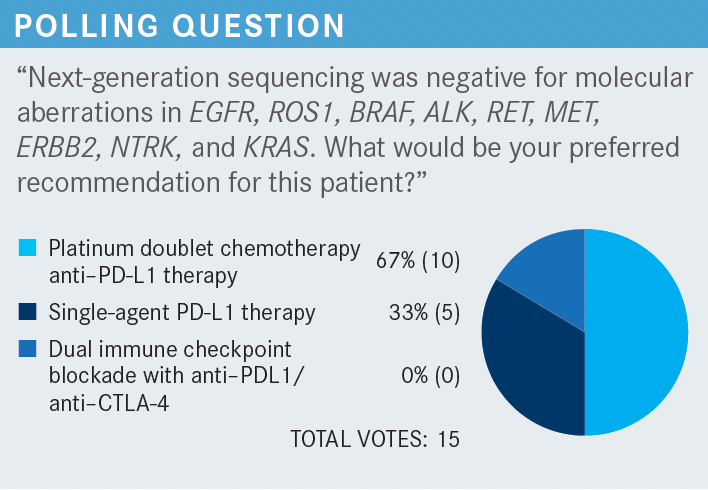

CARBONE: My answer was single-agent PD-L1 therapy. You could argue why you should use doublet and why you should use single agent. I believe the data show they’re fairly equivalent in this population, and that chemotherapy is effective as a second-line agent if you need it. But I have multiple patients who have never had chemotherapy, just single-agent IO, and are doing fine 5, 6, 7 years later.

Many [clinicians] choose a platinum doublet because they say the response rate is a little higher. What is the rationale you would use?

CHOWDHARY: Unless a patient is older or absolutely refuses chemotherapy, are there any other factors that would weigh in? I’ve tended to do both chemotherapy and IO. I think you’re right—the vast majority of experts do feel that with a PD-L1 level of greater than 50%, IO alone is sufficient.

There is a meta-analysis that pooled data from different trials in patients with PD-L1 50% or higher.1 They were looking at patients who received IO alone or chemotherapy/IO in this particular patient population….We’ve known that the response rates are higher, but for IO alone they’re roughly between 45% to 48%. With chemotherapy/IO, they can be as high as 60% to 63%.

There was no survival benefit seen, but because the response rate was higher, and even the progression-free survival was trending better as well. I’ve still tended toward using chemotherapy/IO if a patient is relatively fit and understands that there may be no survival benefit. That’s why I’ve chosen that more often.

CARBONE: You have to understand that in a retrospective analysis such as that, often a real-world analysis, it’s the fitter patients who get chemotherapy/IO and the less fit ones who get single agent. So they would tend to do better just from that parameter alone. You say there’s no survival benefit. I don’t look at response rates so much [or] median survival so much when I look at these curves. My gold standard is landmark survival; 3-, 4-, 5-year landmark survival, how many patients are alive at that point.

The 3-year landmark survival for KEYNOTE-189 [NCT02578680] vs KEYNOTE-024 [NCT02142738] was the same, so why give chemotherapy if it’s not doing anything?

If you give maintenance pemetrexed [Alimta], you’re giving steroids, and you do have edema issues with the chronic pemetrexed. So that’s another issue in my mind.

TEJWANI: Would you comment on high volume, as it is mentioned? You said that response rates don’t matter, but this patient had liver and lung lesions, adrenal and brain; would you weigh in on the patient populations where you would use chemotherapy with IO?

CARBONE: If it’s bulky and overt superior vena cava syndrome or something similar—we don’t have the scans here, but a 9-cm lesion can be in the lung parenchyma and not causing any problems. But a smaller one in the wrong place can cause big problems.

It’s uncommon for me to use chemotherapy/IO in the first line unless there’s an urgent issue and I need a response.

AL BAGHDADI: How about emerging data about the magnitude of benefit from IO vs chemotherapy being better in patients who have KRAS mutation rather than KRAS wild-type, which is the case for this patient?

There are also a few cancers out there where significant or extensive liver metastases have been associated with worse survival when you do IO alone. These 2 issues sway me toward chemotherapy/IO, and if I use carboplatin/pemetrexed, I stop chemotherapy after 4 cycles—both drugs—if I achieve a good response.

CARBONE: Yes, that’s the way to do it. That’s not the way the study did it. If you are worried about the liver metastases, IMpower150 [NCT02366143] showed that patients with liver metastases did better; that’s with the bevacizumab [Avastin] combination.

So again, we’re relying on cross-trial comparisons. There is a clinical trial ongoing, INSIGNA [NCT03793179], that is randomizing patients between pembrolizumab monotherapy and pembrolizumab/chemotherapy. That has 300 patients enrolled already, and so potentially that will help us. We’ve spent decades matching tyrosine kinase inhibitors to driver mutations; it’s unsatisfying to me to just use one size fits all for IO when we know that different patients have different markers.

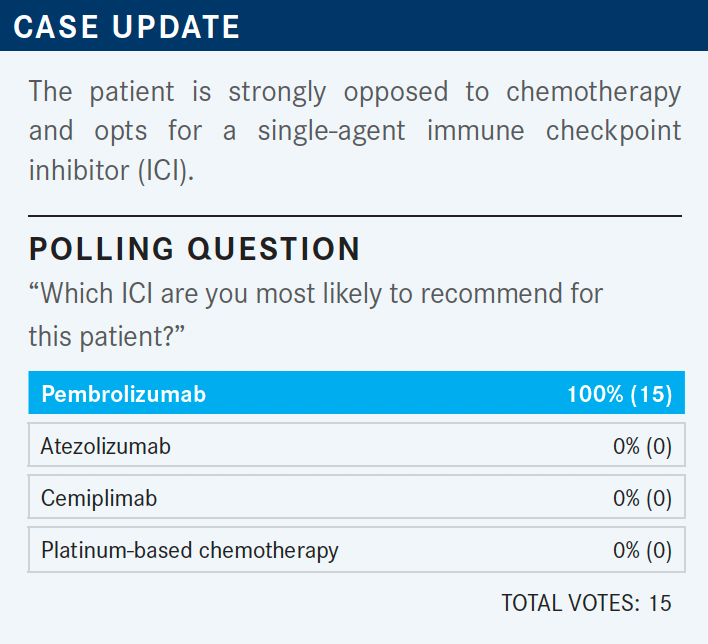

CARBONE: It’s a landslide: Pembrolizumab wins, and that’s not surprising. Physicians are comfortable with pembrolizumab. It had a bunch of early successes in phase 3 trials with impressive results. [Physicians] have been using it for years, and it’s not surprising to me that it has the majority of the market share.

I think there is a concern about liver metastases, but as far as which IO to use in an IO monotherapy setting, pembrolizumab has 3- and 6-week interval dosing—I usually start at 3 weeks to keep a closer eye on the patient, but if they’re stable and responding without toxicity, I’ll go to the 6-week schedule, which is convenient for a patient. Any comments on factors that influence your decision?

NAGASAKA: Is there a scenario when you would consider atezolizumab [Tecentriq] or cemiplimab [Libtayo]? Because as you just mentioned, I go straight to pembrolizumab, especially for the [dosing] reason.

CARBONE: The thing with cemiplimab is it looks great, but we just don’t have the long-term experience with it. Atezolizumab is known to have higher incidence of antidrug antibodies, and a lot of the point estimates with atezolizumab are lower than pembrolizumab in multiple studies. So in this setting, I would go with pembrolizumab for all the reasons we talked about.

CHOWDHARY: In the end, for the vast majority of these various PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors as single agents in [PD-L1]– high-expressing patients, I think the median survivals are pretty consistent with each other. I know pembrolizumab was first past the goal post, and probably has the most magnitude of data, even though hazard ratios are pretty similar. The magnitude of data serve pembrolizumab a lot more in why it’s adopted so much. There’s a lot of experience with it now.

But if you look at the median survivals, they are very similar, in that 22- to 25-month period. That seems to be the median survival for most of these immune therapies in these PD-L1–high expressors. KEYNOTE-001 [NCT01295827] had mature 5-year survival rate data, and these patients who are either treatment naive, or in second/third line were treated with single-agent pembrolizumab. In treatment-naive patients, the 5-year survival was approximately 23% and in patients that had treatment before it was approximately 15%.2 But those are still very compelling 5-year survival rates, and some are even quoting survival rates of up to 30%.

What leads you not to choose pembrolizumab if you’re using it as a single agent in these high expressors? When do you use cemiplimab or something else, if you ever do that, in place of pembrolizumab?

CARBONE: Personally, I wouldn’t use anything else at this point. What might drive me to do that is if cemiplimab data matured, the data showed it was identical, it was one-fourth of the price, or somebody had a huge copay with pembrolizumab, for example. But that’s typically not the case; they price these things within 10% of each other. So that’s not an issue. Right now, the only time I would use something else is in the context of a trial.

AL BAGHDADI: I look at hazard ratio as being close, and maybe these drugs are interchangeable, because even KEYNOTE-024 looked a little better than the KEYNOTE-042 [NCT02220894], if you look at the population with PD-L1 of 50% or higher. They’re both using the same drug. So I don’t look at minor differences between the hazard ratios.

But cemiplimab and pembrolizumab are PD-1 inhibitors, whereas atezolizumab is [for] PD-L1. There are some retrospective data showing that PD-L1 inhibitors cause less pneumonitis. Is that something you see? In my clinic, I see more pneumonitis with atezolizumab and durvalumab [Imfinzi], because that’s what we use for small cell lung cancer, and I believe it’s the disease more than the drug. But there are some data out there arguing it’s less with PD-L1 inhibitors.

CARBONE: Yes, I think there are hints that there are differences. It’s interesting that the 2 approved regimens in small cell are both PD-L1 inhibitors, and the PD-1s haven’t done so well. Maybe for different diseases, a PD-L1 might be better. We just finished a neoadjuvant trial with PD-L1 atezolizumab and had good outcomes in that study.

So who knows? I have no objective reason to decide between the 2 right now, and they’ve never been compared head to head. I’ve seen lots of pneumonitis with the PACIFIC regimen [of durvalumab (NCT02125461)], for example, though that’s in a different context. I’m not sure that there’s a major difference in pneumonitis between them.

MAHAJAN: We have used these drugs from head to toe, from squamous cell skin cancer to lung cancer to endometrial cancer. My experience is they’re all the same. It depends upon what your combination is, whether it’s a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, IO, or chemotherapy—whichever you can get approved and whichever is more convenient for the patient.

We have been looking for answers, from renal cell to hepatocellular carcinoma. I think [if] 1 study shows a little bit better results, it’s not because the agents are different, it’s just the way the study was designed and then done.

CARBONE: And how the patients happened to be chosen. So you’re in the “Coke vs Pepsi” camp here.

Cemiplimab is only approved for patients with greater than 50% PD-L1 expression—same with atezolizumab, but pembrolizumab has the greater than 1% approval, even though the subset analysis showed no benefit. They have different dosing. As I said, pembrolizumab has an every- 6-week dosing.

REFERENCES

1. He M, Zheng T, Zhang X, et al. First-line treatment options for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50%: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. Published online October 16, 2021. doi:10.1007/s00262-021-03089-x

2. Garon EB, Hellmann MD, Rizvi NA, et al. Five-year overall survival for patients with advanced non‒small-cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab: results from the phase I KEYNOTE-001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(28):2518-2527. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00934