Combination Regimens for Multiple Myeloma Show Efficacy in the Transplant-Ineligible Population, According to Dingli

David Dingli, MD, PhD, professor of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic, reviews the combination therapies available for the treatment of multiple myeloma in a patient who is 72-years-old and transplant-ineligible.

David Dingli, MD, PhD

David Dingli, MD, PhD, professor of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic, reviews the combination therapies available for the treatment of multiple myeloma in a patient who is 72-years-old and transplant-ineligible.

Targeted OncologyTM: Do you believe that treating patients with multiple myeloma with multiple therapies in the maintenance setting increases their duration of response?

DINGLI: There aren’t much data on long-term maintenance with multiple agents. I think that it would be an unusual patient with ultra–high-risk disease who will probably go on maintenance with a doublet—for example, lenalidomide [Revlimid] and a proteasome inhibitor at the same time—without much data to support it.

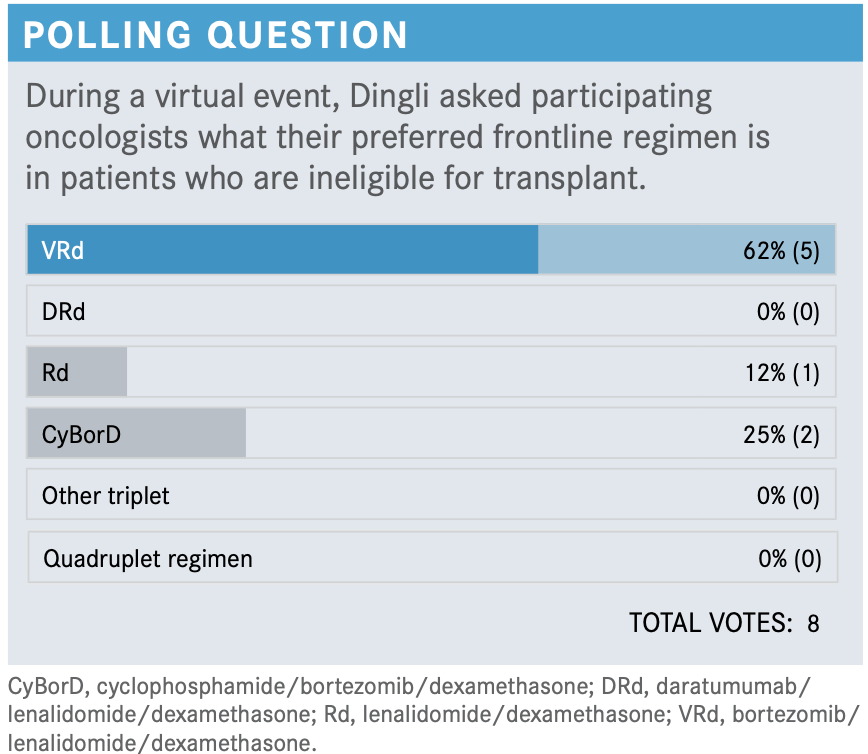

What are the best treatment options for a patient such as this who is not eligible for transplant?

The NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines with respect to therapy in the newly diagnosed setting for non– transplant-eligible patients [say] the preferred regimens are bortezomib [Velcade]/lenalidomide/dexamethasone, daratumumab [Darzalex]/lenalidomide/dexamethasone, or even a doublet with lenalidomide/dexamethasone, or CyBorD [cyclophosphamide/ bortezomib/dexamethasone].1 Other regimens are also included, although probably not many people will use them.

The NCCN guidelines include daratumumab/bortezomib/ melphalan/prednisone [D-VMP] as a regimen because it is supported by a large phase 3 trial that was done in Europe. [They also include], without data, daratumumab/cyclophosphamide/ bortezomib/ dexamethasone, where melphalan is replaced by cyclophosphamide, because of the perceived lower risk of myelotoxicity. But, as far as I know, there is no study that has looked at this in multiple myeloma. There is a study that has come out, looking at this regimen in amyloidosis, and we do know that it’s superior, but not in multiple myeloma at this point in time.

What factors do you consider when choosing an induction regimen for patients like these?

Age, efficacy, logistics, cost, risk status, or, with respect to disease, geography, and performance status.

[Geriatric assessment] is something that is [being] incorporated more and more into clinical trials as part of the assessment of the patient, using various tools such as the Charlson index, etc, to assess frailty of patients and how suitable they are for a specific therapy versus some other therapy.

Which trials have supported the NCCN-recommended treatment regimens in the transplant-ineligible setting?

[There are] many studies in the non–transplant-eligible population.

The MAIA study [NCT02252172] randomized patients to daratumumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone [DRd] versus lenalidomide/dexamethasone [Rd]. The ALCYONE study [NCT02195479] looked at D-VMP versus VMP; we don’t use that regimen [in the United States]. SWOG [S0777; NCT00644228], a very important, large, randomized study in this country, is looking at VRd [bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone] versus Rd. There’s the VRd Lite, which is a variation of VRd where patients get a gentler regimen, often in patients who are rather elderly. Then, there will be studies looking at Rd versus MPT [melphalan/prednisone/thalidomide (Thalomid)], and KMP [carfilzomib (Kyprolis)/melphalan/prednisone] versus VMP, which I do notthink we need to discuss in detail, because this therapy has been rather surpassed.

We can look at some data from the more relevant studies, at how we treat patients nowadays. The MAIA study showed that PFS [progression-free survival] was clearly superior for the DRd versus Rd, with a significant improvement [not reached vs 31.9 months, respectively] and reduction in the hazard ratio by 44% [HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.43-0.73; P <.001].2 ALCYONE showed, again, that the addition of daratumumab to a triplet regimen that includes VMP was associated with significant improvement in PFS, almost 3 times as high [36.4 vs 19.3 months with VMP alone; HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.34-0.51; P <.0001].3 The SWOG study that looked at VRd versus Rd showed that with a rather long follow-up period of 84 months, median PFS was 41 months in patients with the triplet versus 29 months for the Rd doublet [HR, 0.74; P =.003].4 If we look at VRd Lite, the median PFS is approximately 35 months in patients who are not transplant eligible.5

Again, there are other trials that probably are not very relevant to our practice, because most of us will not be using melphalan in patients [with a new diagnosis] or regimens that include melphalan in some form.

Can you discuss the SWOG trial and its results in more detail?

The SWOG study is an important study that probably was a benchmark for a while on how we treat patients who are not transplant eligible.6 [The trial enrolled] patients with no intention to proceed with transplant, randomized to VRd induction, with lenalidomide at 25 mg for 14 days, dexamethasone on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12, and bortezomib given at standard dose IV [intravenously] on days 1, 4, 8, and 11, compared with standard Rd with a 28-day cycle. So, patients received either 8 cycles of the triplet versus 6 cycles of the doublet, and then all patients received lenalidomide and dexamethasone in maintenance therapy. The main outcome was PFS, with overall response rate [ORR], overall survival [OS], and safety [as key secondary end points]. In 68% of these patients, there was a possibility of moving to transplant later, although 43% were above the age of 65. Note that follow-up is substantial, with a median follow-up of around 55 months or more.

PFS clearly favored the use of the triplet therapy, with a 41-month median PFS for the patients on the triplet versus 29 months for the doublet, with a 26% reduction in risk.4

OS was also improved in patients who received the triplet. Median OS could not be reached versus 69 months for patients who were on Rd alone [HR, 0.709; 96% CI, 0.543- 0.926; P =.0114].

As expected, there was some more toxicity in patients who were on the triplet, and the main toxicity was neuropathy with VRd. Grade 3 neuropathy was about 33%.7 This is mainly because, in my opinion, the bortezomib was given every 4 days and given intravenously.

What is different about the VRd Lite regimen?

The modified VRd, also known as VRd Lite, regimen is given with bortezomib on days 1, 8, and 15; lenalidomide is given for 21 days; and dexamethasone is given on days 1, 8, and 15. So the intensity of therapy is substantially lower, with respect to both the dexamethasone and the bortezomib. In my practice, patients who are going to go for VRd Lite will probably not get 40 mg of dexamethasone weekly; rather, I’ll go with 20 mg.

[From] a retrospective chart review, the ORR [with VRD Lite was] around 87%, although the number of patients was not high. The risk of peripheral neuropathy was substantially lower, at 11.6%, although it did increase in time to about 38%, mainly grade 1 and 2.8

Can you tell us more about MAIA?

The largest study that has been done recently in non–transplant- eligible patients was the MAIA study for patients who were randomized to Rd versus DRd.2 Daratumumab was given intravenously. The daratumumab was given, as we know it, weekly for the first 4 weeks, and then every 2 weeks for 4 months, and then monthly. Lenalidomide [was given at the] standard dose, 25 mg for 21 days, and dexamethasone, PO [orally] or IV weekly. The primary end point was PFS; secondary end points were the CR [complete response], VGPR [very good partial response] rates, MRD [minimal residual disease] negativity, ORR, OS, and safety. Most of these patients were elderly, 99%...being older than 65 years of age, with a median age of 73.

The median PFS has not been reached for the triplet regimen, compared to 32 months for the doublet. At 30 months, 71% of the patients on the triplet had not progressed compared to 56% who had not progressed [on the doublet]. It’s too early to look at OS. The ORRs for the triplet were 93%; [there was] stringent CR in 30% and generally higher CR, VGPR, and stringent CR [rates]. MRD negativity [rate] was 24%, and this was, I believe, at the level of 10E-5. Patients who had achieved an MRD-negative state had a lower risk of progression or death in either arm.

The primary end point, PFS, clearly showed an improvement for the triplet regimen, and we’re seeing that patients who achieved MRD negativity, whether on the doublet or the triplet, had a better PFS. This is an important point that keeps coming up with different studies that are looking at MRD negativity—achieving MRD negativity is critical, and it seems what is important is to achieve that state, not how we get it. Now, what people have not shown is whether we can stop therapy after [achieving an] MRD-negative state, or we give limited therapy after that, whether this is true for high risk or for standard risk. I think, for the standard-risk patients, if a patient with that type of disease achieves MRD negativity, one can be fairly confident that they’re going to do very well. I’m not so sure about the high-risk patients. I’ve had quite a few of these, where they achieve an MRD-negative state; unfortunately, it does not seem to be maintained for that long.

[Regarding] the safety characteristics from the study, the main toxicity is hematopoietic; [there’s a] somewhat high risk of neutropenia and some increased risk of infections, especially respiratory infections with pneumonia, as well as sinusitis. Infusion reactions are also common, although thesemainly occur with the first and, at the most, second dose, and after that, it’s not an issue. Now, with the subcutaneous availability of daratumumab, the risk of infusion reactions has virtually disappeared.

How do these standard regimens compare with each other?

[PEGASUS is] an interesting study that tries to address a question that, so far, had not been looked at in a randomized study and perhaps will never occur. So, we know that VRd is considered by many [to be the] standard of care. Now we have DRd. So can one possibly determine which regimen is superior? And because no head-to-head comparison has been done, Durie et al looked at the Flatiron [Health] database, which is a large database of patients with multiple myeloma, where the medical record is available, and they did an in silico study comparing the patients on the MAIA study versus patients who had received VRd or Vd, compared to Rd.9 From the Flatiron database they could identify 2 cohorts so that they could have an internal control, so that the Rd [patients] in the Flatiron database [would do similarly] to patients in the Rd arm of the MAIA study. The study looked at DRd versus VRd, or DRd versus Vd, and they showed that the hazard ratio for response and PFS seems to be in favor of the DRd [HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42-0.71; P <.001]. This is not a randomized study.

From the PEGASUS study, they could show that, at least in this in silico analysis, the patients with DRd seemed to do better compared to even patients who were on VRd or Rd.

The ENDURANCE trial [NCT01863550] was a phase 3 study through ECOG that randomized patients with newly diagnosed disease who were not planning to go to transplant, and who did not have high-risk disease, to therapy either with VRd versus KRd.10 The VRd was given as standard therapy, except that it could be given subcutaneously; the bortezomib could be given either subcutaneously or IV at physician’s discretion. Arm B was carfilzomib, initially at 20 mg/m2 and then escalated to 36 mg/m2. Then, the patients were randomized a second time to either maintenance therapy with lenalidomide for 24 cycles, and then observed, or continue with lenalidomide until progression. Primary end point was OS, with 2 different maintenance strategies of lenalidomide, either fixed duration or indefinite, as well as PFS between the different induction regimens, followed by lenalidomide maintenance. In this study, the primary end point was not met. There is no difference in either PFS or OS, so far, between these 2 regimens.

The 2 arms of the study were well balanced, with a large number of patients. The ratio distribution was similar. There were patients even with an ECOG [performance status score of] 3. The distribution of ISS [International Staging System] 1, 2, or 3 was similar. Almost all the patients had to have measurable disease, fairly standard for this type of study. Virtually all patients had normal cytogenetics, or standard-risk disease. This was a defining criterion for entering the study.

There is no difference whatsoever with respect to both PFS [HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.83-1.31; P =.74] or OS [HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.71-1.36; P =.92]. At the last data cutoff, which was earlier this year, [there was a] median PFS of about 35 months for [both] these [regimens].

There was some increased risk of cardiac, renal, or pulmonary toxicity with respect to carfilzomib; this is expected. [There also was] somewhat more risk of neuropathy in patients who received bortezomib.

How would you approach patients with multiple myeloma who are eligible for transplant?

The standard approach that we take at Mayo [Clinic] with respect to patients who are considered transplant eligible [is that] if the patient has standard-risk disease, defined by trisomies—translocation (11;14) or (6;14)—we recommend 4 cycles of VRd, collection of stem cells, and then proceed to transplant. If the patient decides not to proceed with transplant, [we recommend] 4 more cycles of VRd, followed by maintenance therapy until progression.

In patients with high-risk disease, defined as deletion 17p, t(4;14), or translation (14;16) or (14;20), [we recommend] 4 cycles of KRd or quadruplet therapy. [We recommend] at least 1 transplant. In some of these patients, we consider a second transplant in tandem, based mainly on the studies from Europe that have shown that patients with high-risk disease seem to benefit from a tandem transplant, and then a proteasome-based inhibitor maintenance.

For patients with a double- or triple-hit multiple myeloma, for example, a 17p, t(4;14), or sometimes even 1q or...MYC translocation, we prefer quadruplet therapy, an autologous stem cell transplant [possibly tandem], and then proteasome inhibitor- based maintenance therapy.

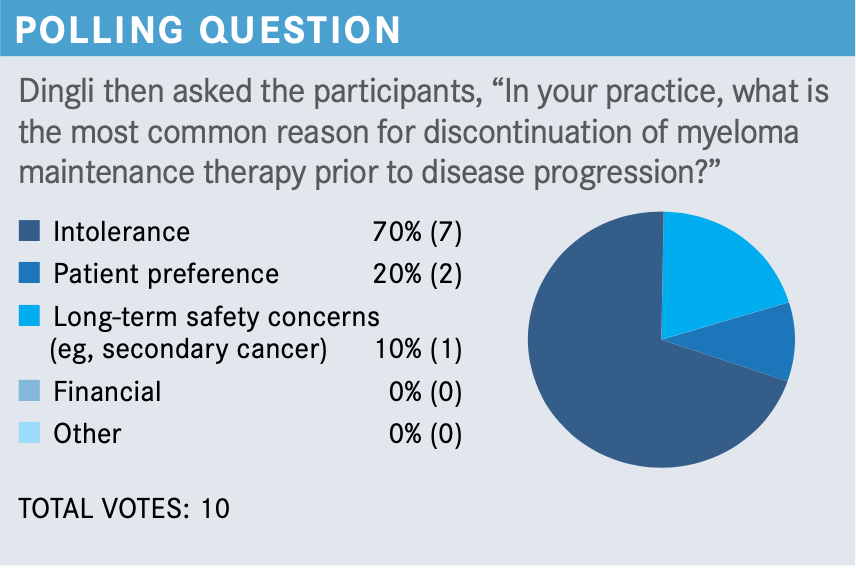

What is your perspective on the results of this poll?

Intolerance seems to be the most common reason, and patient preference. I think these are valid reasons. The risk of second malignancies appears to be somewhat lower. The initial studies from France were quite concerning, but I think over the years we’ve learned that the risk of second malignancies with maintenance appears to be rather low. It’s not 0, but probably somewhere in the range of maybe 2% to 3%. There is some risk. Even in patients who do not receive maintenance therapy, if one looks at the natural history of the disease, some...develop second malignancies independent of maintenance therapy.

REFERENCES

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Multiple myeloma, version 4.2021. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://bit.ly/3omlINH

2. Facon T, Kumar S, Plesner T, et al; MAIA Trial Investigators. Daratumumab plus lenalid- omide and dexamethasone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(22):2104- 2115. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1817249

3. Mateos MV, Cavo M, Blade J, et al. Overall survival with daratumumab, bort- ezomib, melphalan, and prednisone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ALCYONE): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10218):132-141. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32956-3

4. Durie BGM, Hoering A, Sexton R, et al. Longer term follow-up of the randomized phase III trial SWOG S0777: bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone vs lenalido- mide and dexamethasone in patients (Pts) with previously untreated multiple myeloma without an intent for immediate autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(5):53. doi:10.1038/s41408-020-0311-8

5. O’Donnell EK, Laubach JP, Yee AJ, et al. A phase 2 study of modified lenalido- mide, bortezomib and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2018;182(2):222-230. doi:10.1111/bjh.15261

6. Durie BGM, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexa- methasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diag- nosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10068):519-527. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31594-X

7. Durie B, Hoering A, Rajkumar SV, et al. Bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexametha- sone vs lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients (Pts) with previously untreated multiple myeloma without an intent for immediate autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT): results of the randomized phase III trial SWOG S0777. Blood. 2015;126(23):25. doi:10.1182/blood.V126.23.25.25

8. Rodriguez C. Assessing efficacy and tolerability of a modified lenalidomide/bort- ezomib/dexamethasone (VRd-28) regimen using weekly bortezomib in multiple myeloma. Abstract presented at: 17th International Myeloma Workshop; September 12-15, 2019; Boston, MA. Abstract 754.

9.Durie BGM, Kumar SK, Usmani SZ, et al. Daratumumab‐lenalido- mide‐dexamethasone vs standard‐of‐care regimens: efficacy in trans- plant‐ineligible untreated myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(12):1486-1494. doi:10.1002/ajh.25963

10. Kumar SK, Jacobus SJ, Cohen AD, et al. Carfilzomib or bortezomib in combina- tion with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma without intention for immediate autologous stem-cell transplantation (ENDURANCE): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(10):1317-1330. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30452-6

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More