Roundtable Discussion: Morgans Reviews the Use of Cabazitaxel in the CRPC Setting

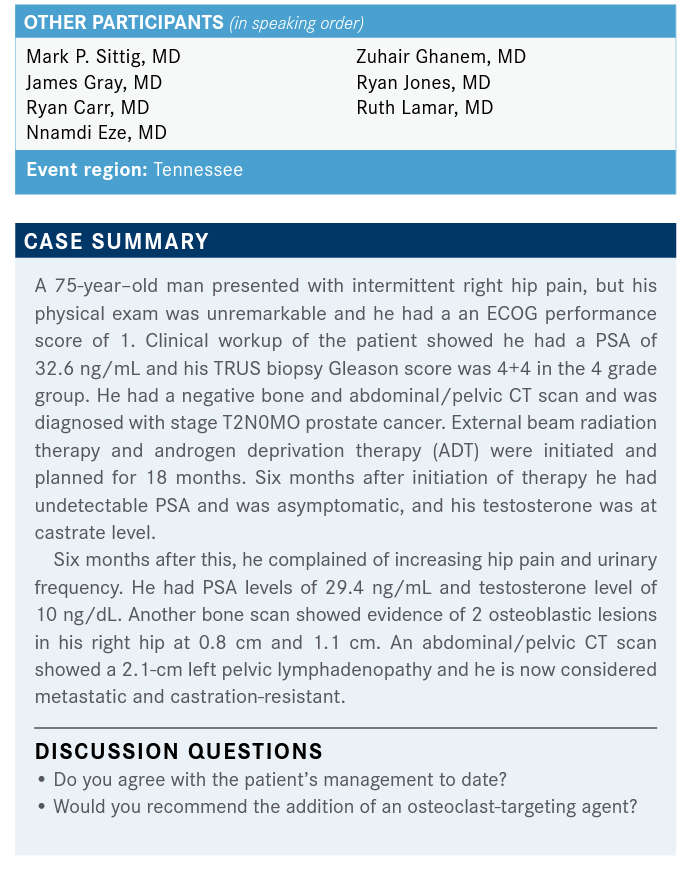

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable event, Alicia K. Morgans, MD, MPH, discussed the case of a 75-year-old man with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Alicia K. Morgans, MD, MPH

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable event, Alicia K. Morgans, MD, MPH, associate professor of Medicine at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University discussed the case of a 75-year-old man with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

SITTIG: I think his work up to date has been NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guideline-driven, [just by seeing they had the] bone scan, and the negative CT abdomen/pelvis. I think the only thing that I might consider including would be 1 of our more advanced prostate-directed scans, like an Axumin scan, but I don’t know if that would be approved in the up-front setting in this patient. Overall, I think his treatment to date has been normal.

MORGANS: I think you’re not far off. Well, [I wouldn’t necessarily use] Axumin, but I think PSMA [prostate-specific membrane antigen], in this up-front setting, will be approved probably more broadly than it already is, in the relatively near future. So that choice makes a lot of sense. Dr Gray, can you give us a second opinion on the management so far?

GRAY: I think the management has been appropriate. I think in Europe, this patient would have had basic metabolic testing for metastatic disease. That’s common there; I believe it’s approved. Axumin is not approved in the diagnostic setting, only in the recurrent setting, but it would be useful in the diagnostic setting, but just hasn’t had FDA approval in that space. Yes, PSMA is approved, but you have to be at the University of California Los Angeles or San Francisco, as I understand, to be able to have access to the FDA approval. Or it must be on a trial setting. We’ve seen them done here at Vanderbilt, of course, on trial and you may have participated in some of those here at Vanderbilt. As I understand, they’ve had access to Axumin and PSMA testing.

That is the future, I think everybody recognizes that. That will give us a better job of going through a little bit of a stage migration, where some of the patients we think have nonmetastatic disease will turn out to have metastatic disease, and that will affect our treatment. Although, even if you’d found osteometastatic disease, you might argue that this patient still would have gotten local regional treatment. Anyway, in today’s world, this patient got treated correctly.

MORGANS: I’m totally with you. I think it will be interesting to see how imaging affects how we stage patients. Because all the trials that we have, all our discussions of localized therapy for these patients, are based on our old imaging technologies. So if a patient still meets criteria for conventional imaging, but now also meets criteria for metastatic disease based on a PET scan, how do we sort that out? I think that actually remains to be seen but thank you for bringing that up.

CARR: Well, when [the patient is] castrate-resistant, as he is now, yes. Seventy-five years old, he’s been on ADT, he’s now castrate-resistant, so I would definitely recommend starting him on denosumab [Xgeva], but occasionally insurance tells me I have to give zoledronic acid [Zometa] instead, but denosumab is what I’d give this patient now.

MORGANS: This patient has mCRPC [metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer], so regardless of his DEXA scan, regardless of his age, he’s eligible for up to monthly dosing with denosumab or zoledronic acid. This is to prevent skeletal-related events. It’s for fragility fracture prevention, which is what we would think about in the hormone-sensitive setting, or localized disease state.

EZE: Many times, you get referrals from local urologists, requesting that we start denosumab on patients with castrate-sensitive disease.

That’s something we get a lot in the rural location, just putting it out there.

MORGANS: Yes. So Dr Eze, you are not just getting those because you’re in a rural setting; you’re getting that because I think there’s a lot of confusion in our field. When patients are hormone-sensitive, even when they’re metastatic, there’s a different dosing strategy, there’s a different indication for treatment. Our goal is really different.

In the hormone-sensitive setting, we are trying to prevent fragility fractures related to osteoporosis, or severe osteopenia. We then use things like the FRAX algorithm, WHO algorithm, and DEXA scans to understand what the 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture or hip fracture is in these patients. We use those guidelines to help us understand if we get either a 6-month dosing, denosumab at 60 mg, or zoledronic acid once a year.

So thank you for bringing that up. That is a pet peeve of mine, and people do that in the hormone-sensitive setting. They just don’t know, I think. In some solid cancers, and in myeloma and things, you can use more frequent dosing of bone health agents to prevent fracture in patients with metastatic disease. But in prostate cancer, in the hormonesensitive setting, the dosing is significantly reduced, and only in patients at high risk of fragility fracture, osteoporotic- type fracture, vs mCRPC, which is exactly how Dr Carr described it, up to monthly dosing of denosumab or zoledronic acid….It’s definitely something that’s confusing, I think, in our field, and people don’t always get it right.

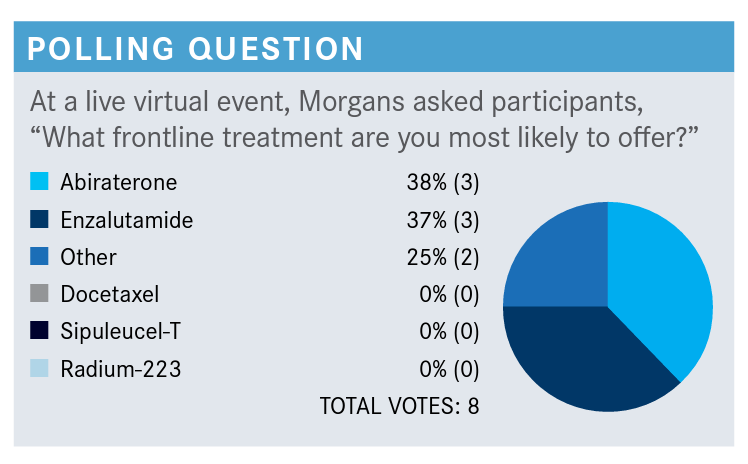

MORGANS: Can someone who said “other” tell me what [choice you would have made,] in addition to the ones that we have here?

GRAY: I was one of the “others.” I might favor darolutamide, just because it seems like it has a little bit of a better adverse event profile….Darolutamide seems to have a little bit favorable profile compared to the others, but I think it’s not been approved in this space either.

MORGANS: Yes, so you make a great point. Darolutamide is only approved in the nonmetastatic CRPC setting. Now, a pelvic node, in some of the studies would still be considered non-metastatic, but I’m just trying to look back here. This patient has a bone metastasis, so he does not strictly fit the criteria for nonmetastatic CRPC. But I would tell you that there are a lot of people who are using darolutamide off label in the mCRPC setting, for reasons like the patient has a history of seizure, the patient has a history of falls, or dementia, or something that might benefit from an agent that does not cross the blood-brain barrier. However, you’re right, it does not actually have the approval here. Here, in the mCRPC setting, I would say we’re mostly talking about abiraterone [Zytiga], docetaxel [Taxotere], enzalutamide [Xtandi], sipuleucel-T [Provenge], or radium 223 [Xofigo].

GRAY: They’re now approving a trial that’s testing darolutamide in this space, am I correct?

MORGANS: There are several trials for darolutamide. I think there is one in the mCRPC setting. There’s definitely a large phase 3 in the metastatic hormone-sensitive setting, in combination with docetaxel. Everyone in the trial is getting docetaxel, and then half are getting darolutamide and half are not. So it’s sort of a triplet approach. But there’s also a metastatic hormone-sensitive phase 2 study that is looking at it in combination in the first line. I believe there’s 1 mCRPC first-line study as well. I think most of those are happening in Europe at this point, but it is being tested, because there’s a lot of curiosity around that drug.

MORGANS: Would you choose radium for this patient? GHANEM: I don’t think so. [Radium 223] is approved for sympomatic bony disease, and it should only be given by itself, without the combination with other agents. So it’s not my preference because the patient was not symptomatic, and it’s used only in symptomatic patients. It’s usually not combined with other agents, so it’s not indicated, in my opinion. I don’t recall this patient being symptomatic in the case.

MORGANS: That’s a great point. This patient did have some hip pain that correlated with some bone metastases, but the patient also had some lymph node disease that was 2 cm or so. We know radium’s not really going to necessarily do anything. In fact, we know it will do nothing for any disease that’s causing lymph node enlargement. So, I totally agree with you there. What about sipuleucel-T, before we move on? Or do you have a preferred treatment that you would use in this setting?

LAMAR: Probably enzalutamide.

MORGANS: Why would you say that?

LAMAR: Either that, or abiraterone, I don’t have a preference over the 2.

MORGANS: I think that’s what most of us would say. I would say the same thing, probably because we’re both medical oncologists, I guess. But a lot of us reach for these AR [androgen receptor]-targeted agents. Enzalutamide’s nice because you don’t have a steroid attached with it; abiraterone is nice as it seems to have a tolerable [adverse] effect profile. In any event, many of these patients are going to get an AR-targeted agent.

JONES: Is that just from the toxicity profile for him, and also because he’s symptomatic?

MORGANS: So he could get sipuleucel-T if he didn’t have symptoms that really required strong doses of an opioid, or really warranted palliative radiotherapy. So sipuleucelT was given to patients who had mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic mCRPC. This is the kind of patient I use this drug in if the patient has very mild symptoms. The goal there is to get it into patients while they have at least 6 to 12 months to live, so it gives an opportunity for the therapy to work. For patients who have rapidly progressive disease, there’s no real opportunity, I don’t think, for them to develop that immune response, and have that durable immune response over time.

It is an interesting therapy in that, I would say, half of oncologists do not believe that it works, and the other half do believe that it works. I look at the survival curves from the trial and say, “People who got it live longer than people who didn’t, and so I’m going to use it whenever I have the opportunity, in a patient who has relatively slowly progressive mCRPC that’s asymptomatic.” And if I can coordinate it to get it done for the patient, because the other challenge for sipuleucel-T is that it is delivered over a relatively brief period, about 6 to 9 weeks. It’s 1 treatment, basically every other week. But the problem is you have to get it coordinated between, for us, the Red Cross is drawing off their blood, doing apheresis to pull off their antigen-presenting cells. Then they must come into clinic to get reinfusion about 2 days later, and they repeat that process every other week. That can be a little taxing for patients and can be challenging for clinics to logistically coordinate. I do use it, again, in asymptomatic patients, or very minimally symptomatic patients, who have at least 6 to 12 months to live, so that I think that they can actually reap the benefits of training their immune system. But, we don’t know in whom it works, and in whom it’s just fluff.

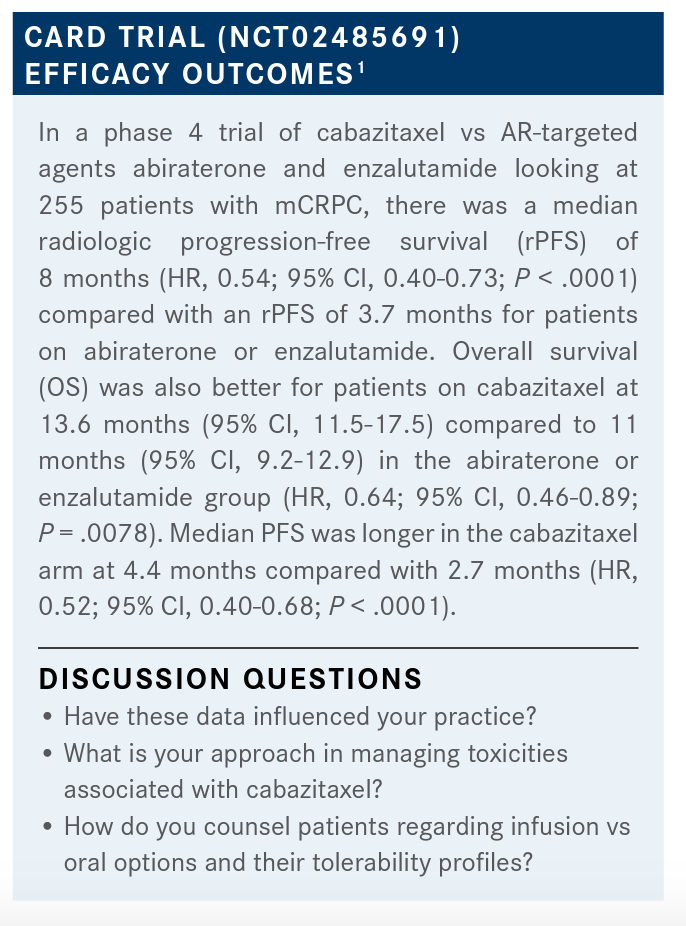

SITTIG: I am the one who was unsure [of how these data would impact my practice]. I was not aware of these data prior to this evening. It is very compelling, certainly in the castrate-resistant setting. One of the things that I think about, although I might not directly be prescribing these medicines, is what kind of toxicities or adverse events the systemic therapies for these gentlemen will have, as they may be on them for a significant amount of time. So certainly anything that has fewer toxicities in this castrate-resistant setting would be something that I would be interested in.

MORGANS: What do you think about the toxicities associated with cabazitaxel? What’s your overall take on that?

EZE: I love cabazitaxel. In fact, if I could use it first-line in my patients that I’m considering for chemotherapy, I would. Obviously, it’s much better than tolerated; in fact, you can dose it at 20 mg/m2, and that’s even better tolerated. I think the data are quite impressive, and I have had some good results in my patients.

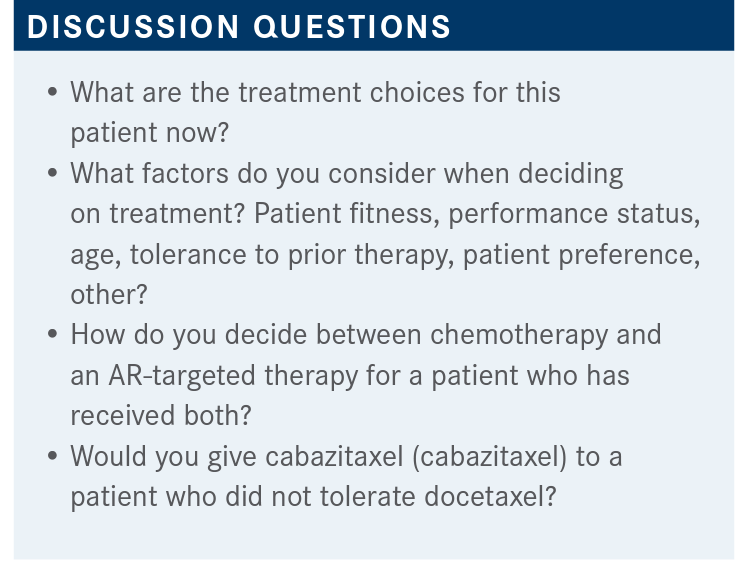

MORGANS: Well, that is good to hear. It’s interesting; I use the 20-mg/m2 dose myself. I think that it has been well tolerated, and that’s why I go to it. There are young patients occasionally that I’ll crank up the dose, but usually I stick at 20, and it seems to have pretty excellent response rates there. Dr Ghanem, I’m curious, for you, do you talk to your patients about going to a second AR-targeted agent, or going to cabazitaxel? Do these kinds of data come into your conversation at all?

GHANEM: Yes, of course. The point about it is the patient usually perceives oral chemotherapy, or oral therapy, as more well tolerated, better tolerated than [intravenous (IV) therapy] and you tell them sometimes it’s not. Sometimes, really, the IV is better tolerated. Sometimes all these oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and skin rash. That’s more difficult to manage than an IV chemotherapy, so I usually start my discussion with the patients not necessarily that it is an oral agent but that it might have a better quality of life than an IV agent. Because, people go and read, and they come to you, and they say, “Someone has a pill, or someone recommended a pill.” And then, you must explain this to them. That’s where I usually start my discussion, the tolerability and the [adverse] effect profile is something we would consider, based on the circumstance, and based on his own situation.

Regarding the targeted agent, you remember when you asked the question, “Would you test first for BRCA mutation, or MSI [microsatellite instability], before you give the cabazitaxel?” And, you said that’s probably also a right answer. I think it’s a right answer there because this is a time where would you discuss what is like, if the patient MSI is high, so you can give pembrolizumab [Keytruda] and you can give cabazitaxel at that point. You would see if the patient had autoimmune disease, or if the patient has other issues, you will lean more toward cabazitaxel. If the patient has a lot of neuropathy, and so you would start talking about pembrolizumab. That’s where this targeted molecular testing, and genetic testing, early in the disease come in the long-term planning.

MORGANS: I completely agree. We are not practicing in an oasis that only includes AR-targeted agents and cabazitaxel. We’re practicing in a setting where we now have access to genetic testing for germline and somatic testing, and we have these other options, too. It’s exciting because our patients do have more options. So, that all makes sense.

I wonder, Dr Lamar, are you finding patients who are fit, maybe, for chemotherapy, but because of COVID-19 are thinking about using alternative therapies? Does that come into your conversation at all when you’re talking about chemotherapy with these patients?

LAMAR: Sure, patients are much more afraid to pursue chemotherapy because of COVID, and I think that’s getting better, but yes, that has come up several times in a variety of cancers.

GRAY: Well, as a radiation oncologist, where [COVID-19] probably impacted us most was the patients in whom we could successfully delay therapy. Probably the biggest example of that was a patient, for example, with limited early-stage prostate cancer who had low-risk prostate cancer. “You should just do active surveillance” became more of “you really should do active surveillance” because you don’t want to have to treat a disease that’s almost certainly never going to kill. It could affect your quality of life many years down the road, and in the process of trying to eliminate this disease, expose yourself to this virus.

But there were a lot of other patients. Patients who had high-risk disease, who were on androgen deprivation therapy, and there’s a lot of data that says that you can delay them. Now, this has been out and been published in short order. I was surprised that you can delay that therapy about 6 months, and you probably don’t lose the ability to even cure a locally high-risk patient. So that’s how it impacted my practice, as much as anything. Now, how it would impact some of these other patients, with ongoing aggressive, now multiply resistant, recurrent metastatic disease—that’s a different issue. Because, if you delay their therapy substantially, that could have a huge impact. That’s not something I’ve had to deal with on a day-to-day basis, because I don’t make those decisions, being a radiation oncologist.

References:

1. Fizazi K, Kramer G, Eymard JC, et al. Quality of life in patients with metastatic prostate cancer following treatment with cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzalutamide (CARD): an analysis of a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 4 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(11):1513-1525. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30449-6

Conservative Management Is on the Rise in Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer

January 17th 2025In an interview with Peers & Perspectives in Oncology, Michael S. Leapman, MD, MHS, discusses the significance of a 10-year rise in active surveillance and watchful waiting in patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer.

Read More