Roundtable Discussion: Chen Explores Biomarkers and Staging for Acute GVHD

Based on case details, Yi-Bin Chen, MD, and a group of peers discussed the probability of a patient developing acute graft-versus-host-disease and how to treat the disease.

Yi-Bin Chen, MD

Based on case details, Yi-Bin Chen, MD, director, BMT Program, Cara J. Rogers Endowed Scholar at Massachusetts General Hospital, and associate professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and a group of peers discussed the probability of a patient developing acute graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD), and how to treat the disease.

CHEN: We [get] consent from these patients prior to transplant, and we try to believe in this theory of informed consent. It’s very difficult. We talk about all the risks, sequelae, and complications that can happen. We talk about aGVHD, other ways you prevent it, and the way we treat it. But ultimately, I think we’re trying to let patients know what the risk is for them to develop this complication.

CHEN: What do you think about in terms of when you’re talking to a patient about the risk for something to happen? What would you say the overall risk is to develop some form of aGVHD that requires some type of therapy?

KADDIS: I haven’t worked on a transplant unit in several years, but I generally used to warn patients that they have a greater than 50% chance of having some grade of aGVHD. Sometimes it’s mild, grade 1 or 2, and that’s often manageable. But other times it’s a little more severe. I used to generally discuss that the 3 organs most affected are usually the gut, the liver, and the skin and that treatment would usually be aimed at modulating the immune system, basically.

CHEN: I think that that’s a fair risk; we say somewhere between 25% and 50%. If you look at the published series between large centers, it can vary from 25% all the way up to 70%, even in the same type of transplant platform. A lot of that is due to how aggressive you are at diagnosing aGVHD, specifically that of the upper gastrointestinal [GI] tract. At Massachusetts General Hospital, in looking at our last 5 years, we probably have about 25% to 30% total risk for this patient because they received myeloablative [conditioning and had an] unrelated donor—probably a little bit higher than that, maybe 30% to 35%. What we see, though, at other centers may be a little bit higher.

JOYCE: If you think about GVHD as whether it is going to be severe enough that systemic steroids are going to be required as a break point, rather than whether the patient needs a skin biopsy that a cream is going to deal with— we all go around and grade people, but if you’re going to have to pull out intravenous methylprednisolone for a patient, then that makes a difference in how they’ll do and that’s where the inflection point changes on outcome. It’s not grade 1 or 2. I tell people there is a 1 in 3 chance they’ll have bad enough [GVHD] that it’ll be a risk to their overall well-being.

CHEN: One can see that the risk is there, and certainly we have room to improve upon trying to lower that risk. What are the specific risk factors for this patient at diagnosis?

JOYCE: He had an older woman as a donor.

CHEN: Yes, so certainly it’s interesting. The National Marrow Donor Program won’t even accept potential donors over the age of 50 now, and then once you’re past 60 years of age, you’re not even allowed to give. There are several reasons for that; studies have shown that the younger the donor is, the better the outcomes are. One of those drivers, as Dr Joyce gets at, is the incidence of aGVHD.

The other risk factors would be the myeloablative conditioning. We didn’t go into specific agents, but certainly the more total body radiation that’s given, the higher the risk there is. An unrelated versus a related donor, though they are fully matched, in the era of precise molecular typing— one can debate those data—but the unrelated donors probably still have a bit of a higher incidence of aGVHD.

As the patient goes forward, in terms of what happens to that patient, do they develop aGVHD? Do they have horrible infectious complications? Do they get clostridium difficile infection from being on antibiotics? These are all things that we think about going forward that help shape our risk.

These things don’t [always] change what we do. Perhaps the type of prevention that’s given is dictated by the type of donor, but along the way it doesn’t change how we manage to prevent outcomes. That is probably something that has to change. We have to see how patients do in real time [and decide if we] should change our management to ultimately be able to change their outcomes.

These days, when someone presents with aGVHD, we have a whole team that’s alerted to the new patient. It’s like when you have a new patient with AML and the team needs to know, so you alert the people who need to do the bone marrow biopsy, the pathologist, and then any clinical trials you want to get them started on. It’s the same thing these days for aGVHD, which is good. It shows we’re doing research. A lot of companies have taken interest in developing agents for GVHD and provide support. We often send biomarkers that we’ll touch on to try to restratify patients, and we have clinical trials targeting different phenotypes of aGVHD. It used to be we treated everybody the same, and, hopefully, we’re getting to a place where that changes.

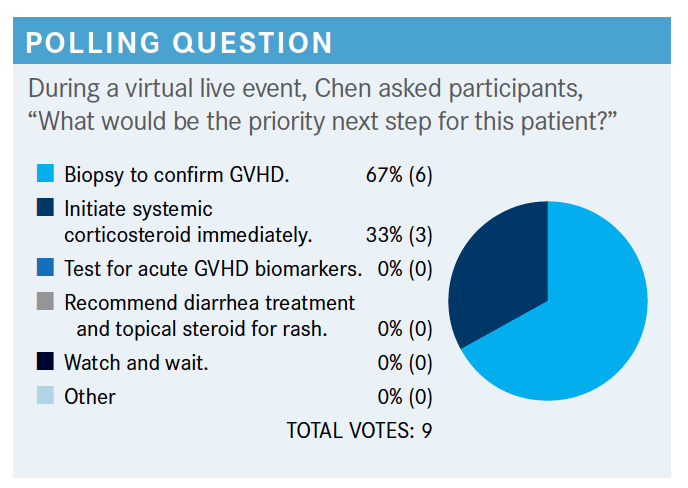

Usually, these patients are discharged somewhere between day 15 and 20. He’s coming back for his first follow-up visit, probably. He talked about how he’s eating and also then his bowel movements, and he’s having about 4 episodes a day of watery diarrhea, which is new over the last couple of days. The volume of the diarrhea is certainly difficult to quantify for an outpatient when they first present. I don’t know if you ever tried to have that conversation with patients; it’s almost impossible. So really, we could quantify it as 4 episodes a day.

CHEN: I don’t think there is a right answer here. Both of [the chosen options] will probably be done fairly quickly. Even in the age of clinical trials for new aGVHD, we don’t have time to wait for studies or screen for things to come back because we feel the disease can worsen rather quickly, especially when you have visceral involvement like GI disease.

I think testing for GVHD biomarkers is still somewhat experimental. It’s a commercially available test you can send out. The biomarkers that are most mature are looking at GI mucosal biomarkers called ST2 and REG3α. They are thought to be a quantification of mucosal injuries or like a proponent for your GI mucosa. That’s shown in a lot of studies and analyses to be prognostic for GVHD. But we certainly don’t have the license to change our therapy or think we can change outcomes or change treatment based on what those biomarker show. I think an increasing number of centers are sending those biomarkers. I’m not sure people are using them to make decisions. We have clinical trials that will break people up based on those biomarkers to test different therapies.

Diarrhea treatment and topical steroids—I think all of us would agree that’s supportive therapy that [is used for] everybody, but it’s not the priority. I don’t think any of us would watch and wait. I think if it’s a little bit of a skin rash it might be different, but if there’s GI involvement, I think all of us would certainly take action.

JOYCE: Regarding the biomarkers for gut GVHD, how specific are they for, say, somebody who has CMV enteritis or another inflammatory condition in the GI tract? Do you think that they’re specific enough to be able to distinguish those?

CHEN: That’s a great question. The biomarkers, I should specify, are mainly prognostic, so they are not diagnostic biomarkers and they’re not GVHD specific. They are merely markers of mucosal damage or mucosal injury. Anybody with any reason to have mucosal injury will have elevated biomarkers, and anybody who’s very sick after transplant will have elevated biomarkers.

They’re not meant to differentiate in the setting of an ill patient between aGVHD and some other complication. They are meant for once you’ve made the diagnosis of GVHD to able to prognosticate. Even though they’re GI mucosal biomarkers, they’ve been shown to work in patients with liver or skin disease, but that’s likely because these patients haven’t yet developed gut disease but will, and you’re just catching the beginning of the mucosal injury. It is really important to emphasize the point you’re making, Dr Joyce, which is that these are not diagnostic biomarkers, and we don’t have diagnostic biomarkers.

The diagnosis of GVHD, at least aGVHD, remains at a clinical diagnosis. I think we should make that point, too, even though most of us would do a biopsy of the gut here. We generally do a flexible sigmoidoscopy and take random biopsies from the GI mucosa.

There’s no specific pathological pattern for GVHD. There’s supportive pathology such as crypt dropout, apoptosis, neutrophilic abscesses, and so forth, but you can see that type of pattern in other complications as well. A lot of us don’t do a lot of skin biopsies because they’re very nonspecific. In the gut biopsy we’ve seen them in the setting of other complications. But in the right patient, a biopsy helps confirm the diagnosis and, importantly, it rules out other entities such as CMV enteritis.

The important thing is the 60% body surface area and 4 episodes a day of watery diarrhea for 2 days. Since they’re just coming into the hospital now, we don’t necessarily know the volume of their diarrhea, which has traditionally been important.

The grading systems have somewhat evolved over the last couple decades, but they’ve mainly stayed the same and been consensus driven. It’s still pretty primitive. We look at the skin and the body surface area of involvement, we look at the liver and the height of the elevation of total bilirubin, and we measure the volume of diarrhea that patients have on a daily basis. That perhaps is the most disappointing aspect of our current grading and management because volume of diarrhea is affected by so much. It’s affected by how much a patient decides to eat or drink, it’s affected by antibiotic use, it’s affected by narcotic use if they have pain—all those things. That’s been a huge flaw in how we grade severity of patients and also for clinical trial end points.

The most modern consensus-driven guideline was developed by the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium [MAGIC]. The skin, liver, and GI tract are broken down by the criteria of what I said. MAGIC did also add if you can’t get the volume [of diarrhea] based on being an outpatient and presentation, you could look at the number of bowel movements a day for grading as well.

Based on this, individual organs are staged, and those individual stages add up to an overall grade. This patient has a stage III skin, based on 60% body surface area involvement. There’s no liver involvement. Then, based on 4 episodes of watery diarrhea, it looks like just a stage I lower GI. If you then take those stages, you come across an overall grade, so stage III skin and stage I lower GI looks to be an overall grade II. Grade II, some of us feel, is not that severe.

CHEN: We admit the patient to the hospital, we do our diagnostics, and a third of us said we’d start steroids immediately, which I agree with while we’re doing the diagnostics. Anybody have an idea what dose of steroids we would use for this patient?

LIN: It’s early to make the patient take methylprednisolone.

CHEN: I agree. Standard therapy for most patients, especially those where you’re worried about gut involvement, has been 2 mg/kg of methylprednisolone in divided doses twice daily. That’s probably about 2.5 mg/kg of prednisone total, just to normalize it to a prednisone dose. That is generally standard therapy.

There are some places where if it’s grade 2 disease or skin-only disease, we start at 1 mg/kg of prednisone, thinking patients don’t need as much. It’s useful to point out, we’ve never had a randomized trial to compare different doses of steroids, so it’s hard to know what’s the right dose. But for this patient I think it all comes down to how serious we think his gut involvement is in terms of how aggressive we want to be with treatment.

JOYCE: Although the portion of people who die of treatment- related mortality die of infection in the setting of GVHD, so more is not always better up front. You have to put out the fire, but there’s a high risk of infection if you stay on 2 mg/kg.

CHEN: Yeah, there’s a big push for who we think about as low-risk patients to either use steroids and taper faster, or perhaps not even use steroids at all and use alternative agents if we have access.

We generally feel for the higher-risk patients we want to give steroids plus another drug if you get better responses. For the lower-risk patients, if we can accurately identify them, we want to taper steroids faster or use something else.

REFERENCE:

Harris AC, Young R, Devine S, et al. International, multicenter standardization of acute graft-versus-host disease clinical data collection: a report from the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(1):4-10. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.001

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More