Roundtable Discussion: Cohen Leads Examination of Therapy Decisions for CLL During COVID-19

Jonathon B. Cohen, MD, MS, moderated a Case-Based Roundtable event during which experts discussed treating patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jonathon B. Cohen, MD, MS

Jonathon B. Cohen, MD, MS, an associate professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, moderated a Case-Based Roundtable event during which experts discussed treating patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia during the COVID-19 pandemic.

COHEN: One thing that I am curious about is how [your practice] over the past year [has been affected by] COVID-19. Have you been less likely to start patients on therapy, or has it changed the way you think about treatment?

WANG: I think for me, patients are more reluctant to get intravenous [IV] treatment. They’re OK with oral treatment, though. I present all the available options like VEGF versus BTK [Bruton tyrosine kinase] inhibitors, and most of my patients prefer oral options, even though it’s unlimited duration versus limited duration.

COHEN: Is it just because they’re trying to avoid having to come in?

WANG: Yes, and to avoid the other neutropenic risks, monitoring for [adverse events and complications]. They don’t care about taking a pill for a long time, and they don’t want all the monitoring and all the visits.

COHEN: I’m curious if: At some of the other sites that are represented, have patients been similar in wanting to try to avoid IV therapies?

THOMAS: Yes, that’s been my experience also. Most of the patients don’t want chemotherapy, and then with the obinutuzumab [Gazyva] depleting the γ-globulin sometimes, they’re worried about infection, and the number of times you must come into the office to get checked. So I think they prefer oral options as well.

MCKINNEY: I haven’t thought about this as much in CLL. We’ve certainly tried to avoid CD20 antibodies and hospitalization. I have concerns that even the BTK inhibitors also decrease, at least now, the [COVID-19] vaccine response, so there’s been a lot of moving parts. Certainly, we try to avoid IV therapies, chemotherapy, hospital admissions, and then, probably in some patients, try to delay treatment as long as possible or put them on oral therapies.

COHEN: The general question for me is how you think about a newly diagnosed patient’s [factors], or what are some of the things that you’d be looking for during your prognostic evaluation?

LUKE: I look for the [immunoglobulin] status and del(17p).

COHEN: Do you typically order that for all your patients with new diagnoses?

LUKE: Yes, I do. I order CLL prognostication, so they do give you that information, especially if I’m trying to treat and if it is a very early stage.

COHEN: I’m curious: Do you typically include FISH [fluorescence in situ hybridization] and IGHV in your standard prognostic workup as well for all your patients?

PATI: We have a standard panel; the pathologists automatically order that.

COHEN: That’s typically what I do as well.

SAWHNEY: As soon as [we] send the flow cytometry, you get a [note] back from the pathologist saying that it’s CLL, and they automatically check off the prognostic panel. Oftentimes, I have to say no to it because there are so many patients who are diagnosed with CLL and they’re not going to be treated for years. I don’t think that every single person should have the whole panel done, even if they have del(17p) and they’re not on planned treatment at that time; I don’t think it’s necessary.

COHEN: If you were going to treat somebody when it’s time for therapy, do you typically include it then?

SAWHNEY: Even if you have the panel from 2 years ago and you try to treat them now, you’re going to have to repeat it anyway, so what’s the point of doing it for everyasymptomatic patient?

COHEN: Right. I can say, at least in my own experience, I typically do order it, but I have a handful of patients just like you that I don’t for that exact reason. I find that sometimes you have somebody who’s totally asymptomatic that feels well, and you almost regret ordering it because then it gives them something else to be worried about for the next 4 or 5 years before they need treatment.

SAWHNEY: The pathologists are pushing it, and like I said, I keep getting first request, second request, third request from GenPath [Diagnostics] saying that they want to do it, and I keep saying it’s not needed. I have people with del(17p) and they’ve been asymptomatic for a year or 2. It’s just more worry for them and for me at this point.

COHEN: For me at least, the key is when you’re going to treat somebody. I think it’s very helpful to have that information, and in many cases, for most patients it’s helpful. But I agree with you: For somebody that’s either very elderly or infirm or who has a white blood cell count of 11,000 mcL and it hasn’t changed in quite some time, [I would not get it]. I think it’s appropriate in those situations to hold off. I’ve had some patients specifically ask me not to check it, because they’re aware of it, and they’d rather just not have to know about it or deal with it.

COHEN: Are there any other tests that you typically order for untreated or patients with newly diagnosed CLL?

COHEN: We started to look at TP53 a little bit more frequently, but otherwise, I typically do the FISH and the IGHV as well. Would anyone reflexively do a cyclin D1 test? The concern would be mantle cell lymphoma [MCL] could also present with a lymphocytosis, but is that something that you guys think is mandatory, or is it more of a case-by-case basis?

STEFANOVIC: I do it in every patient because one sometimes is surprised with similar presentation occasionally in a patient with MCL that otherwise would have passed for a CLL. The FISH panel otherwise might not make a distinction, so the cyclin D1, I think, is necessary.

LUKE: Pathologists usually do it before they make that complete diagnosis, whether it’s a CLL or a CLL with MCL.

COHEN: With MCL, sure. I think our pathologists often will do that as well.

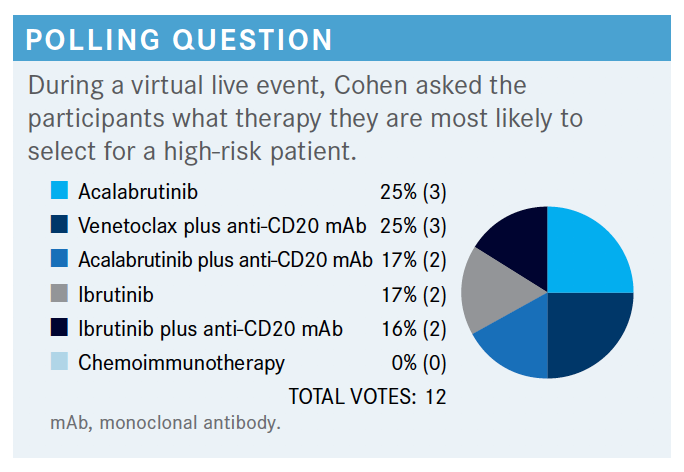

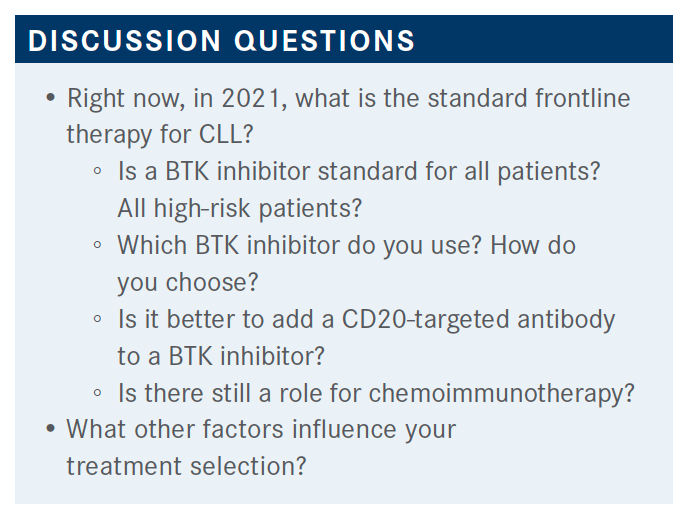

COHEN: This is about what I would expect and what I’ve seen in my own practice….The one thing I would agree here is that chemoimmunotherapy is probably not going to be the best option for a patient with high-risk features. Otherwise, I think you could probably make an argument for any of these other options. In the NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines, for frail patients with significant comorbidities, or those over the age of 65, or young patients that have comorbidities,acalabrutinib [Calquence] plus or minus obinutuzumab, ibrutinib [Imbruvica] monotherapy, or obinutuzumab and venetoclax [Venclexta] are all in their preferred regimen category.1

For patients younger than the age of 65 without significant comorbidities, those same options are available. So in most cases you can see the NCCN would recommend a BTK or venetoclax-based approach.

COHEN: Do you typically recommend a BTK inhibitor for all your patients, all things being equal, if they’re candidates for it? Or are there particular patients that you think of for BTK inhibitors and others where you think about something else?

PATI: For certain patients, particularly individuals with atrial fibrillation, if you can, use the venetoclax-based regimen. You can still think about chemoimmunotherapy for young patients who do not have high-risk features. I don’t like it as much, however, especially with the COVID-19 situation.

COHEN: Would [anyone else] standardly use a BTK inhibitor? And why is that, as opposed to other options?

THOMAS: I think there are some patients that would prefer time-limited therapy. For those patients, the venetoclax/obinutuzumab [combination] would be a good option, but by and large I would go with the BTK inhibitor [in the] first line. One thing I am concerned about: I’m not sure about this, but I think there are more data using BTK inhibitors and then when they fail, going onto venetoclax-based regimens, as opposed to the other way around. I don’t think there’s as firm evidence; I could be wrong on that.

COHEN: There have been reports of both, but there is a venetoclax trial specifically for BTK-pretreated patients. I think that’s probably a fair statement.

SAWHNEY: I chose the venetoclax and CD20 combination. I haven’t needed to admit anybody through COVID-19 for the venetoclax [treatment]. We do it all as outpatient. I really believe in time-limited therapy. [If a patient is 60 years old], how long are you going to treat? If the patient was not able to get venetoclax and they have [congestive heart failure] and they have other issues, then I would go with a single-agent BTK inhibitor, but otherwise I would choose the combination treatment.

COHEN: It’s challenging to weigh these, but if you were going to choose a BTK inhibitor, I’m curious how folks decided between using ibrutinib or acalabrutinib instead.

SAWHNEY: For the patients that I have given BTK inhibition, I’ve started using acalabrutinib more often than ibrutinib because it has much less chances of atrial fibrillation and bleeding complications. So I’ve pretty much moved away from ibrutinib to acalabrutinib.

COHEN: Somebody that maybe chose one of the ibrutinib options: How do you decide which to use, and do you typically stick with ibrutinib, all things being equal?

WANG: I still stick with ibrutinib, just because of the experiences I have had with ibrutinib over the years, and also, it’s once a day versus twice a day. With acalabrutinib you have to make sure the patient’s not on a proton pump inhibitor [PPI]. Most of my patients are older.…It’s a lot easier to ask them to take twice a day and make sure they’re not on a PPI, because sometimes I don’t see them for 3 months.

I think in the data for adverse events profiles, there are more similarities than differences. I’ve talked to them up front about what to look out for [and told them that for] therapy adverse effects they must call me or my nurse right away. So I’ll stick with ibrutinib mainly for the convenience of drug interaction. I think it’s easier, and I’ve had great success with ibrutinib.

COHEN: In the COVID-19 era, [has everyone] been more anxious about using venetoclax due to the [tumor lysis syndrome] risk, or do people feel comfortable that this can be managed in clinic with oral hydration and potentially going to the infusion center?

SAWHNEY: I think it’s all over the place. People who have reasonably good insurance that I can see as an outpatient are more reliable. I tell them to take their medication and show up at 7 AM in my office and I can take care of them.

Where I cannot give them ibrutinib and I’m stuck with acalabrutinib, and [the case is] too high risk, those patients I’m a little hesitant to give venetoclax. But again, I moved predominantly to venetoclax up front because of limited therapy.

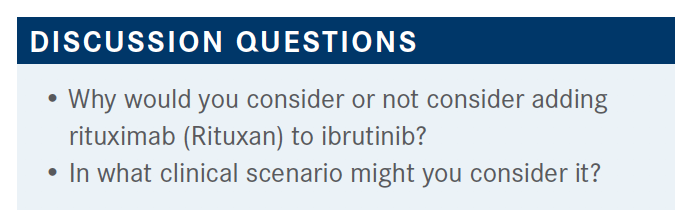

COHEN: Why would you not consider adding rituximab to ibrutinib for a young patient?

WANG: I would not consider it because when I use ibrutinib, I’ve never done it with a CD20 antibody, whether it’s rituximab or obinutuzumab. I don’t think that it really adds additional value to overall survival [OS] because I don’t think this is curable. I think it depends on what the goal of treatment is, if it’s symptom relief or progressionfree survival [PFS]. I think it adds more toxicity and inconvenience if we were going to use ibrutinib.

COHEN: That’s a fair point. I know for a lot of patients, maybe one of the reasons that they choose this option is because it’s oral and they don’t have to come in and out of the infusion center.

WANG: As far as I know, there’s still no cure for this disease unless there’s an OS benefit. Usually with ibrutinib, I see a response quickly. It depends on what we are trying to treat. Usually these symptoms go away fast; lymph nodes shrink fast. If white [blood cell] count stays up, who cares? I tell the patient up front. So I’ve never [added a CD20 antibody]; I probably will never do it with ibrutinib.

LUKE: I think the progression looks better, and I give the option: Do you want PFS or OS? Most of the patients want to be free of their disease for a longer period, so you give the best treatment up front and then there are so many medications coming, we can look at different options later. Also, by using rituximab, the white blood cell count may not go high, just like [with] ibrutinib alone, and so people get so worried about white blood cell count going up, which helps in that setting, too.

COHEN: Is there anybody that might use it in some instances and not use it in other instances, that used some sort of a clinical factor to decide whether to use rituximab?

MCKINNEY: It’s a loaded question. We’re enrolling patients to Alliance studies that still have that as a backbone, so there are combination trials, and I’m not vehemently opposed to it. I don’t routinely do it, but I guess if there’s some reason for pushing a little bit harder for quicker response, or there’s hemolytic anemia or something, you can add the rituximab. I don’t routinely do it to get a PFS benefit unless it’s on a study.

COHEN: One question that comes up all the time is “What do you do with a patient that develops atrial fibrillation or develops hypertension while they’re on a BTK inhibitor?” How do you typically manage atrial fibrillation, for example, in a patient that you put on ibrutinib or acalabrutinib?

WANG: If [the patient] developed atrial fibrillation, I would send them back to the cardiologist right away, and if it can be well controlled, I would continue the BTK inhibitor.

SAWHNEY: A lot of my patients are older, and single-agent therapy seems like an easy thing, but I’ve had patients who had occasional atrial fibrillation, were asymptomatic, and then they were not on any anticoagulant.

You start them on ibrutinib, and they end up with symptomatic atrial fibrillation, and then they need a blood thinner, and then they’re bruising.

So I try to stay away from ibrutinib in this situation, and I would give them 1 year of therapy. However, that’s another reason I stay away from ibrutinib—because the atrial fibrillation becomes a real challenge, especially when they’re on a blood thinner.

COHEN: Is hypertension something that you’ve seen in any of your patients that have received a BTK inhibitor? How do you typically manage that when that develops?

PATI: I really don’t manage hypertension much these days; even though we could, usually the primary care provider manages that. Acalabrutinib [has a] somewhat lower incidence of atrial fibrillation, but it can still cause atrial fibrillation.

So the problem is with the BTK inhibitor as a class, unless you decide to try something different. I prefer to adjust the dosage down a little bit; might help, may not. We might have to change it if it becomes a problem. That’s all the problem with the BTK inhibitors with atrial fibrillation, especially with a blood thinner

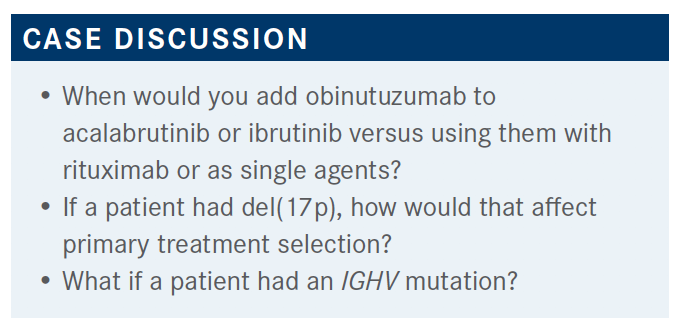

COHEN: Would del(17p) necessarily change the way you might treat an untreated patient?

WANG: Not really for me; I just watch them a little bit closer.

THOMAS: I would generally go with a BTK inhibitor in that case, and I don’t see very much value in adding the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies to those patients.

The response rates seemed a little bit higher, and maybe there’s some PFS improvement, but I don’t think there’s OS benefit.

COHEN: If a patient is IGHV mutated, is there anyone that would still consider chemoimmunotherapy? Maybe stepping out of the COVID-19 era, say, if we were having this meeting 15 months ago, would you consider chemoimmunotherapy, or are people pretty much almost exclusively moving to oral therapies at this point?

SAWHNEY: I think that there is still a very small percentage. [For instance, I want to give a 55-year-old patient 6 months of therapy], and, hopefully, they’re having some reported cures. That’s the only person that I would try the FCR [fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab] on, basically.

COHEN: I think that’s fair. That’s the group that I at least have that conversation with.

LUKE: I use it usually in the older populations. I tend to use venetoclax and rituximab and decrease their dose a little bit, and they tend to tolerate it well. I have more experience with venetoclax and rituximab than BTK, so I still use it in these patients.

REFERENCE

NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma; version 4.2021. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://bit.ly/3y6Fm6N