Roundtable Discussion: Examining MRD as a Prognostic Factor in Transplant-Eligible Multiple Myeloma

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable event, Olalekan O. Oluwole, MD, MBBS, MPH, leads a discussion around identifying prognostic factors for a patients with transplant-eligible multiple myeloma.

Olalekan O. Oluwole, MD, MBBS, MPH

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable event, Olalekan O. Oluwole, MD, MBBS, MPH, assistant professor of Medicine of Hematology/Oncology at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, leads a discussion around identifying prognostic factors for a patients with transplant-eligible multiple myeloma.

KHASAWNEH: For a prognosis, I typically quote patients the data from the ISS [International Staging System] and the Revised ISS trials to discuss with the patient about outcome. I’m always cautious when I talk to my patients about prognosis. I tell them these are average numbers… we have available.

As far as transplant eligibility, it’s a combination of factors where we [look at] patient-related factors, performance status, comorbidities, and organ function. I tell them before a transplant, we typically put the patients through a rigorous evaluation process. It’s not only about the comorbidities they have. They must have a good, strong social support system. Geography is also key. I try to keep the patients informed that this process is a bit long and the transplant time is a rigorous one, where we have to dedicate at least 1 to 3 months of their time for this process. But in the long run, there is always the survival advantage.

The good thing about it is that it decreases the time where they will be requiring treatment, especially intense treatment. Maintenance treatment is much better when they have a second-, third-, or fourth-line of therapy. With young patients, it’s in the eye of the beholder. Typically, the European-defined age is by the chronological age; however, here in the United States we focus more on physiological age. But definitely for anyone above the age of 75, I try to [stay] away from transplant.

OLUWOLE: As you were talking, it also occurred to me that many of our patients are going to get a lot of information overload, and they’re going to get easily overwhelmed about how many things you have to address immediately, particularly when you’re just telling them that they have a diagnosis.

ERTER: I would agree with a lot of what was said just now….With prognosis I tend to discuss the data-driven points via ISS, as noted. I put a little bit more of a rosy spin on it given a patient who has, let’s say, standard risk and doesn’t come in with plasma-cell leukemia or something like that. I am stressing that there are new treatments coming out that we really expect patients, in general, to do quite well on for a long time in broad strokes.

I think that’s a great point that was made earlier that we, in the United States, are physiological age dependent. If the patient was presented at 51 years old with anemia and [high IgG], I would be sending for transplant. Young patients—in my practice, under 70 years is for sure young. Between 70 and 80 years [it then depends on] how good of shape they’re in.

OLUWOLE: When we’re talking about transplant eligibility, do you think patients who are newly diagnosed should hear it at that time [of diagnosis], or wait and let them hear about transplants along the way?

KASSIM: The way I approach this is, you have to factor into context the current data. What the current data are telling us is that a few factors are probably important in your patients’ prognosis. That is attainment of minimal residual disease [MRD]. It’s now clear that whatever approach you use, if you can achieve MRD, it correlates with better prognosis long term. Of course, you factor in high-risk cytogenetics, and people are now beginning to look at molecular profiling.

What we know from transplant, also based on some of our published studies, is that it’s quite clear that transplant as consolidation, irrespective of local therapy, deepens patients’ MRD. Up front, I like to throw it out there that there are local therapies, but at the end of the day, based on reduction in terms of MRD, that may translate into long-term better survival as well as overall survival.

In terms of young age, I agree with the other speakers. You factor in both physiological and chronological age. If organ function is good and the patient is a good age between 70 and 80 years, I think it should be done.

BALA: In terms of discussing prognosis with the patient, the information I give [depends on] how much the patient expects, especially during the initial few visits. I don’t overload them with all the information at once.

If they ask specific questions, I give them the information. If not, I just give them the information that they need to know for the next step and then gradually fill them in on what to expect. That seems to work for most patients.

OLUWOLE: At what age will you try to say, “Well, this is probably not going to be a transplant candidate,” and maybe not refer them?

BALA: At about 70 years, I think carefully if transplant is a reasonable option. But in the healthy 70-year-olds who don’t have other serious comorbidities, I still consider it as an option. If they are willing, I will refer them at least for a discussion.

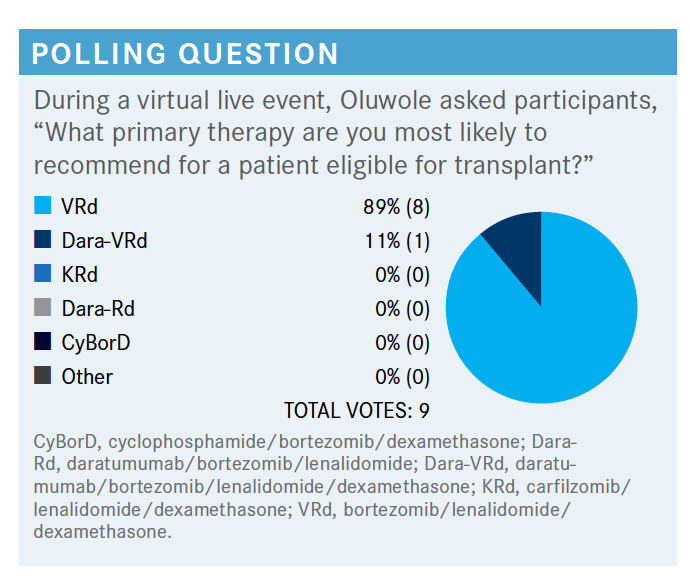

OLUWOLE: People are either thinking VRd [bortezomib (Velcade)/lenalidomide (Revlimid)/dexamethasone] or dara-VRd [daratumumab (Darzalex)/bortezomib/lenalidomide/ dexamethasone]. What do you do in your own practice or what would you do for the transplant-eligible new diagnosis?

BALA: VRd has been the go-to regimen for a long time. There are new data with dara-VRd, but still, I haven’t fully adopted that. So far, VRd has still been my go-to regimen, but I’m still looking for more convincing [data] to switch to dara-VRd. But it may happen soon.

ERTER: I know at Emory [Winship Cancer Institute] and a few academic centers that dara-VRd has become the [popular] nontrial treatment. I haven’t switched to that yet. There are not superstrong data, and I worry about some reimbursement issues with that. But I think the sense is that that’s coming, and it’s interesting to hear that the data have been adopted at some centers as sort of the de facto choice.

PEACOCK: I think that most of us in community oncology see multiple myeloma pretty irregularly. [At the academic centers], you see it all the time. We see it once or twice a year, new diagnoses. I think for most of us the problem is what regimen is next.

My 25 patients that have multiple myeloma have gone through multiple transplants and have lived long enough to see 1 regimen after another after another; it’s interesting how fast new drugs are developed. I’m just waiting for the dust to settle to see what the best thing is.

Approaching that older age, I’d skip the transplant. I would get the best regimen to give them a major response and I’d move straight on to engineered T-cell therapy. But we’re not there yet, right? By the time I’m 70, maybe we will be. I’d like to know what you think about that.

KASSIM: There’s a rule of thumb that if you can’t cure a disease, then sometimes you have to come up with your best option to improve survival. Even though we’re not there yet, there are so many drugs coming to the market, we have to determine at some point how you prioritize therapy.

Nowadays, people are incorporating MRD. I think in patients who may not go toward transplant, try to get into an MRD negative status may justify thinking about, if they can tolerate it, a 4-drug regimen.

But for patients who are going to transplant, a quadruplet drug regimen up front may help unless you want to restratify them to higher-risk disease. Part of those data are a little lacking. But like I said before, your ultimate goal is to get them to an MRD status. Whether you use VRd, CyBorD [cyclophosphamide/bortezomib/dexamethasone], or KRd [carfilzomib (Kyprolis)/lenalidomide/dexamethasone], the important thing is to get them to MRD before transplant.

Most of those patients, based on our own data at Vanderbilt-Ingram [Cancer Center], will go into a full complete response [CR] and MRD status if they get on autologous transplant. The only thing that will make the difference is if you measure MRD.

It doesn’t matter how you get there. It’s whether you get there. That’s what is important, because we know patients who don’t enter stringent CR or negative MRD status are more likely to relapse sooner. Whether you use VRd or dara-VRd, if you can attain MRD status post transplant, then you are less likely to progress within the next year or so.

OLUWOLE: What aspects of a therapy are most important to you in a transplant-eligible patient with a new diagnosis of multiple myeloma?

KHASAWNEH: In taking a patient to transplant, you need to make sure that the patient is achieving, preferably, a CR. This is No. 1.

Second thing is whether the patient has cytogenetics; to include proteosome-based treatment in the induction therapy with the transplant. You need a triplet therapy, preferably VRd. If I can get the patient on dara-VRd, I would love to, but the problem is that with insurance companies, it’s getting difficult to incorporate daratumumab in the frontline setting with any combination therapy.

If I have the luxury of incorporating daratumumab into the induction, I would definitely do it. But with the payer issue, most of the time when I try to incorporate daratumumab into VRd or CyBorD, for that matter, we get denial pretty fast.

OLUWOLE: What are the important goals of frontline therapy?

CARR: Getting people into MRD-negative status seems to correlate with better overall responses. But stringent CR, another category, I think is a very important thing; also, trying to get people there as quickly as possible so they’re not exposed to too many drugs and then have problems mobilizing and things like that. Those are all pretty important to me and my frontline patients.

OLUWOLE: When patients are at advance-risk status and you want to give them at least the 3-drug regimen, are you comfortable with that, or will you also try to figure out a way to reach out for daratumumab in that group?

CARR: I had a patient like this. She had high-risk cytogenetics, was a bit older and frailer. I started her on VRd and I gave her a couple of cycles. She was responding and I sent her to [someone who said to add daratumumab], and we were able to. We got it approved and she had a nice response, but she had very aggressive disease. After 3 or 4 cycles, she went to the transplant unit for evaluation. She started relapsing or she became refractory, so I had to put her on something different. So in 1 patient I’ve been able to get dara-VRd. She tolerated it pretty well, other than some anemia. It didn’t get us to where we needed to be, but I’d feel comfortable using it again in high-risk patients if I could get it approved.

OLUWOLE: How about in the transplant-eligible patient? If you can get them into a stringent CR with a 4-drug regimen, what then would be the need for a transplant?

ERTER: You’re asking a great question. I think outside of the patient being enrolled on a clinical trial, I would still default to at least a transplant evaluation in someone who knows myeloma more backward and forward than I do to make that evaluation.

That said, overall one of the driving points of our discussion is the idea of MRD negativity and what we are gaining by continuing to treat these folks. I think if you skip the transplant, then I would be hard-pressed to take the foot off the gas and not be fairly aggressive moving forward. It’d still be maintenance treatment but probably something more than lenalidomide at 2.5 mg a day. I think that it would be a pretty complicated discussion about what to do absent a transplant.

OLUWOLE: What is your [preferred] proteosome inhibitor?

KHASAWNEH: Bortezomib continues to be the proteosome inhibitor of choice up front. Ixazomib [Ninlaro] is difficult to get approved in the frontline setting but is still a viable option. It’s an all-in-one, especially if the patients live far from the treatment center.

OLUWOLE: If you had a patient where you give them the VRd but they are sluggish to respond, would you add daratumumab and then keep giving them the VRd?

ELKHATIB: I think it could be reasonable to talk to the patient about adding an extra drug. Also, if you give them VRd, for example—I don’t know if you are using it weekly or twice a week—I think most of us are using it weekly now. Maybe you can consider using it twice weekly, or I think it’s better to add daratumumab and, hopefully, you will get a better response.

OLUWOLE: Are you using MRD assessments routinely in your practice?

ELKHATIB: To be honest with you, [MRD] is not really a common test that I’m using in my daily practice. Maybe I should use it more often, but I usually go with the usual lab data. I think MRD would be better done on bone marrow biopsy. We don’t subject our patients to too much bone marrow biopsy.

KASSIM: At Vanderbilt, it’s been standard of care for the last couple of years. All bone marrow is done in Vanderbilt as standard of care, always assessed with 8-color flow cytometry, which is an accepted standard for examining MRD status.

GHANEM: I don’t use it frequently because I believe it’s useful mostly at the time of transplant, which usually the transplant team takes care of. Once the patient starts on maintenance therapy, I use the blood work and the bone marrow biopsy to watch the patients after the transplant. So I didn’t use it that much in my practice.

Usually what I do depends on where I practice. I used to practice in Michigan, close to Mayo Clinic, and their system is different from where I practice now, where I send my patients to Vanderbilt. It usually depends on where the transplant team that you work with is and what they [do]…before the transplant, when they want to see the patient and what their protocol is. They usually take care of the MRD [testing] in a patient who is a transplant candidate.

Once the patient is on maintenance therapy, I follow up with the routine testing that we do on the bone marrow and the light chains and the blood work, more than doing the MRD itself.

OLUWOLE: If they refer a patient to you for autologous transplant [who has] stringent CR and is MRD negative, would you turn them away? Or would you still transplant someone who is MRD negative?

KASSIM: There’s a difference in MRD, too.…Some people will set 10-4 as the standard for MRD. Some will say 10-3. We think, when you say you’re MRD negative, at the end of the day, there are different scales to the depth of response, and that’s what matters.

OLUWOLE: I think you’re echoing what we all feel, that it is an incurable disease. Our technology is limited by how deep we can measure, but regardless of how deep it is, if we can get it deeper with drugs, it’s even better.

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More