Molecular Testing Leads to Better Results on Olaparib for Patients With mCRPC

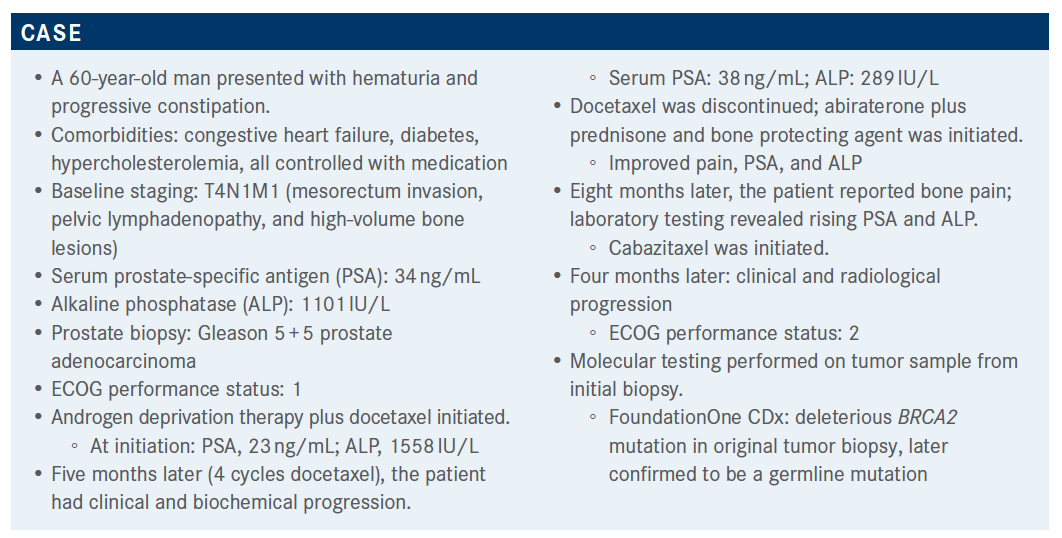

Findings from the PROfound and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for molecular testing were reviewed for a discussion on treatment for 60-year-old man with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Daniel Landau, MD

Findings from the PROfound and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for molecular testing were reviewed for a discussion on treatment for 60-year-old man with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

The virtual Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable discussion was led by Daniel Landau, MD, a Hematology and Oncology professor at Orlando Health Cancer Institute.

Targeted OncologyTM: What underlines your approach to BRCA testing, and when do you typically test for the mutation?

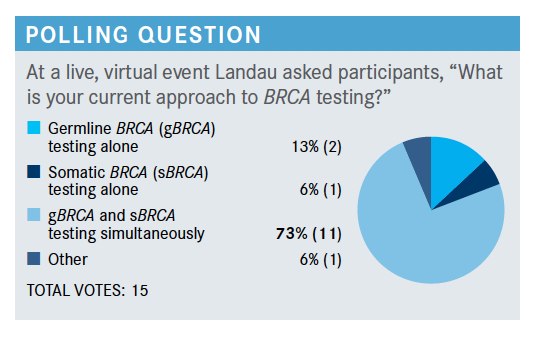

LANDAU: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] now says that anybody who has high-risk disease presentation should be sent for germline testing early on in the disease course, more so now than ever. I am referring patients to [genetic] counselors, who are really going to be dedicated to the germline analysis. However, I am probably doing more of the somatic testing when patients are progressing on other therapies. So I think I tend to do germline very early on and somatic a bit later, but that’s just my bias.

What was the design of the phase 3 PROfound (NCT02987543) study that looked at this specific patient population?

These men [on the trial had] mCRPC and had to progress on a prior drug such as an enzalutamide [Xtandi] or abiraterone [Zytiga]. They had to have some form of mutation. Now, there [was] a randomization here between BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, and several other mutations. The patients were then randomized toward olaparib [Lynparza] or physician’s choice.1

The physician’s choice was mostly a switch from either abiraterone to enzalutamide or enzalutamide to abiraterone. They were also allowed to cross over if they were not doing well on whatever the physician’s choice was. Again, this was a 2-cohort study.

What were the efficacy results for patients on this trial?

Particularly in cohort A, there was a very large separation between [olaparib and the control arm], which was maintained at about 17 to 18 months [HR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.25- 0.47, P <.001), so a clear benefit to the use of olaparib compared with the control, keeping in mind the crossover design that was used here.2

This is a new take to put them together, and the [results] come a bit closer together when you include cohort B. So there is still a benefit when you look at both cohorts together, [with a median progression-free survival of 5.8 in the olaparib arm and 3.5 months in the control arm], with a hazard ratio of 0.49 [95% CI, 0.38-0.63; P < .001]. However, there was a bigger separation with cohort A alone.

Interestingly, there were a few mutations that didn’t really seem to make a big difference, and some of these could be affected by low numbers [in the study], but maybe there are some groups that were underrepresented. [However, for patients whose tumor harbored an ATM mutation], there was a lot of interest [that the] early-on group didn’t seem to do as well as the BRCA-mutated population. [Other tumor mutations that] didn’t seem to get that benefit from olaparib also included PP2R2A. ATM, I think, was a bit of a disappointment to everybody, as we expected to see something similar to the BRCA [response].

Was there other relevant efficacy data from the PROfound trial?

[There was a secondary analysis that looked at BRCA1/2 or ATM alterations.] In cohort A, which was patients with BRCA1/2, or ATM tumor mutations, the key secondary end point was overall survival [OS]. This has the adjusted crossover design that basically showed what likely would have happened if they didn’t allow crossover. [Median OS was 19.1 months in patients on olaparib compared with 14.7 months (HR 0.69; 95% CI, 0.50-0.97; P = .02) in the control arm.] In the overall population, if you include cohort B, [the median OS was 17.3 months vs 14 months (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61-1.03)], where the OS Kaplan-Meier curves seem to come together some.3

Furthermore, the confirmed overall response rate [ORR] in cohort A was about 33% [in the olaparib group]. We saw some deep responses, mostly partial responses, but you did see quite a better response. And [in the other cohort], we really wouldn’t expect much response.1

Median duration of treatment [DOR] was 7.4 months compared with about nearly 4 months [for physician’s choice]. Discontinuations [due to treatment] were as high as 16% with olaparib [compared with 8.5% in the control arm]. Dose reductions were also fairly common; about a quarter of the overall patients had to have a reduced dose.

What were some of the adverse events (AEs) here?

The most common AEs included anemia, nausea, fatigue, decreased appetite, and diarrhea. I think we probably came into the study expecting anemia [to be the most common] based on the experience in the gynecological cancer world. That was by far and away the biggest grade 3 issue [at 46.5% overall and 21.5% in the olaparib arm]. Pulmonary embolism was also an issue as well in about 4% of patients. The point that I always like to make is that you see a risk of clotting with the PARP inhibitors.

How is olaparib used in the clinic?

Based on the PROfound data, olaparib is approved for any homologous recombination repair [HRR] gene–mutated patient with advanced prostate cancer.⁴ These patients had to have prior exposure to enzalutamide or abiraterone.

How does the indication for rucaparib (Rubraca) differ from that of olaparib?

[This was based on the TRITON2 study (NCT02952534)], which was rucaparib [given to patients] at 600 mg twice daily. The HRR gene was also similar to what I discussed before. What we saw in patients with BRCA mutations in their tumors [was that there] are more somatic than germline [mutations]; basically 2:1 of somatic status versus germline, highlighting the importance of both really.5

The main end point here was a radiographic response [RR] and ORR. There was a very good ORR of 43.5% [95% CI, 31%-56.7%], and the PSA response was a bigger percentage of patients. You don’t see a lot of complete responses, but you do see a lot of partial responses or even stable disease, and some of these responses can be relatively long lasting. Radiographic PFS was 9 months [per blinded independent radiology review assessment]; however, OS data were not yet mature. Time to PSA progression was about 6.5 months in this study.6

Now, in terms of the non BRCA mutations, the investigators didn’t see a ton of objective response. They certainly didn’t see a large complete response, and you saw some partial response and mostly stable disease. The median time to PSA progression was short, and confirmed PSA response was much lower than previous studies.

In the TRITON2 study, there were treatment-related adverse events [TRAEs] that are going to be seen a lot across any clinical trial.⁷ Dose reductions were as high as 30%, and treatment interruptions were seen in about 48% of patients. Discontinuation was low, though, only about 6%, which tells you that you may have to play with the dosing a fair amount or give patients some breaks here or there. But at the end of the day, most patients can tolerate rucaparib.5

In terms of the most commonly reported AE, the fatigue and asthenia were similar to what’s been reported previously and were high [at 44.7% in any grade]. Anemia was high, but there were not a lot of other grade 3 events that were reported.

The caveat here is that rucaparib is FDA approved but has a narrower approval than olaparib does. Rucaparib is relegated to just the BRCA-mutated population, and in this study, patients received both the prior antiandrogen and a taxane containing chemotherapy.8

What are your thoughts on the expansion of biomarker testing based on these approvals?

The NCCN guidelines have now incorporated both rucaparib and olaparib as second line of treatment. In order to go on these, patients have to have prior therapies with abiraterone or enzalutamide.9

I remember when I started treating prostate cancer, the NCCN guidelines were basically 1 page, because all we had was Lupron [leuprorelin]. It has become much more complicated nowadays, which is a good problem to have. But olaparib and rucaparib have now been included based on which mutation is being identified.

References:

1. Hussain M. PROfound: Phase 3 study of olaparib versus enzalutamide or abiraterone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene alterations. Presented at: European Society of Medical Oncology; 2019; virtual. Abstract 5059. https://bit.ly/3r6xw8o

2. de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al. Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2091-2102. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911440

3. Hussain M, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al; PROfound trial investigators. Survival with olaparib in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2345-2357. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022485

4. FDA approves olaparib for HRR gene-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. News release. FDA. May 19, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2021. https://bit.ly/3jIugw6

5. Abida W. Preliminary results from TRITON2: a phase 2 study of rucaparib in patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) associated with homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene alterations. Presented at: European Society of Medical Oncology; October 21, 2018; virtual. Abstract 3619. https://bit.ly/3f9Misy

6. Abida W, Patnaik A, Campbell D, et al; TRITON2 investigators. Rucaparib in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer harboring a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene alteration. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(32):3763-3772. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.01035

7. Abida W, Campbell D, Patnaik A, et al. Non-BRCA DNA damage repair gene alterations and response to the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: analysis from the phase II TRITON2 study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(11):2487-2496. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0394

8. FDA grants accelerated approval to rucaparib for BRCA-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. FDA. May 15, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2021. https://bit.ly/3qgIh7v

9. NCCN. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prostate cancer, version 2.2021. Accessed March 22, 2021. https://bit.ly/3f56V9i