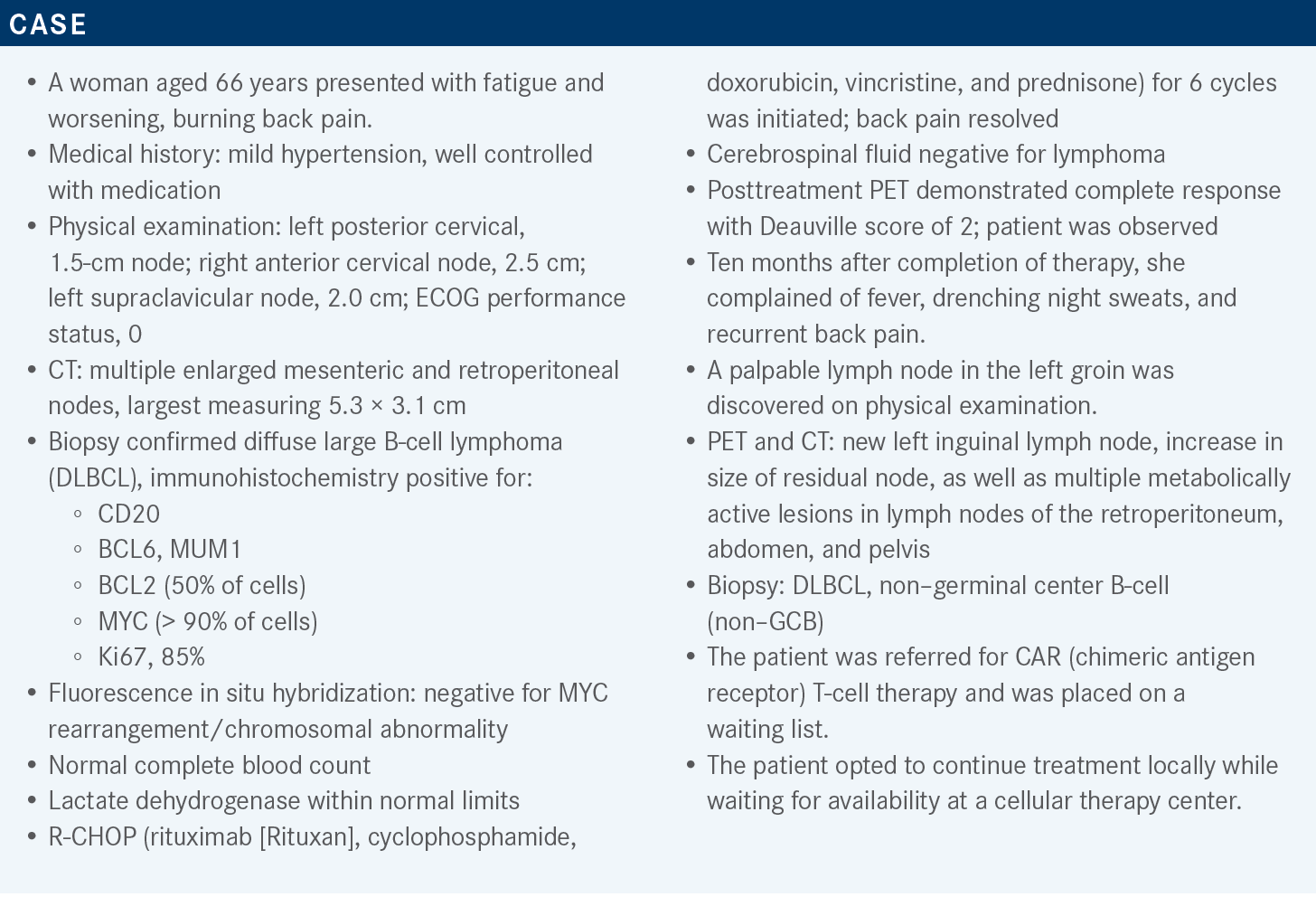

Mohrbacher Compares Available Treatments for a Patient With DLBCL Post Chemotherapy

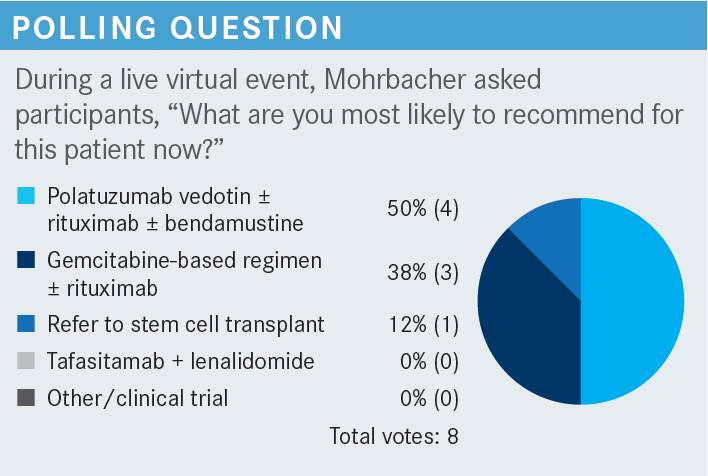

During a Targeted Oncology™ Case-Based Roundtable™ event, Ann F. Mohrbacher, MD, discussed second-line therapy for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Ann F. Mohrbacher, MD

Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine

Medical Director, Autologous Bone Marrow Transplant

Keck School of Medicine of USC

Los Angeles, CA

Targeted OncologyTM: What are the recommended second-line therapy regimens for patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL who will proceed to transplant?

MOHRBACHER: Based on the NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] classic pathways for patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL and its cousins, we have the DHAP [dexamethasone, cytarabine, and platinum (cisplatin)] combination.1 Virtually every [combination] has rituximab: R-DHAP or R-ICE [rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide] are by far the most common ones used, at least in most of the big cities. It was previously common to do a gemcitabine plus platinum trial, but now it’s being replaced more by oxaliplatin [GemOx]. It is more common in terms of patients I see who were referred to me for either transplant or CAR T-cell therapy, so GemOx with rituximab usually and often with a steroid in there. I don’t see ESHAP [etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin] used much anymore but I think, to be fair, the other regimens are a little easier. GemOx has the advantage of being outpatient, so that’s a nice choice for places where it’s hard to get in for ICE or R-ICE.

Now we have an option in the more refractory patients or the patients who have relapsed early—we can debate what we call early—that leads us to offer the anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy. We have axicabtagene-ciloleucel [axi-cel, Yescarta] and lisocabtagene-maraleucel [liso-cel, Breyanzi], with category 1 evidence supporting axi-cel. One must decide if the patient is going to get to CAR T-cell therapy on time, [and] if they’re going to add their insurance approval and then collect the T cells. Is it safe to wait those 3 weeks or so? The CAR T-cell center should be telling you this is going to take 3 weeks from the day it’s collected, or 2 weeks, or 4 weeks, and maybe you should put the patient on some therapy in between if there’s a high rapid growth rate.

[If it] is not a rapidly growing relapse and the patient can wait for 1 week, maybe give GemOx and rituximab as outpatient treatment. But if it’s a rapidly progressive case, I don’t think most of us are going to be as comfortable with that option. [For example,] a lot of us would choose to go with R-ICE.

Another newer option, whether they’re going to go to transplant or CAR T-cell therapy, would be pola-BR [polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy), bendamustine (Treanda), rituximab]. That is incorporating a moderately active chemotherapy drug, rituximab like every other salvage regimen, but also the new anti-CD79 antibody-drug conjugate [ADC] to give it a different mechanism of action, given this is probably a patient who’s showing some chemotherapy refractoriness if we’re considering CAR T-cell therapy.

If a patient is not going to receive transplantation, what are the second-line options?

If they’re not a candidate for transplant, they might also not be a candidate for CAR T-cell therapy. There are the simpler chemotherapy regimens like GemOx and rituximab, the pola-BR regimen, tafasitamab [Monjuvi] plus lenalidomide [Revlimid], the new R2 [lenalidomide, rituximab] for large cell, or an anti-CD19 antibody.

We have a lot of older chemotherapy regimens that are not used much anymore. We’re not usually going back to anthracycline-containing regimens. This patient already had R-CHOP, but we could take the anthracycline out and use [R-COP], but these are not commonly done now because we have much better, probably more effective options that bridge immunotherapies.1

If there’s nothing else to use and we have a patient with B-cell lymphoma who is CD30 positive, one might end up using brentuximab vedotin [Adcetris], an established ADC, BR [bendamustine, rituximab], or even ibrutinib [Imbruvica]. It’s getting to be more hit or miss when you get to that. R2 was developed more as a follicular regimen rather than for large-cell lymphoma, but we know it does work sometimes.

We have maybe a better, more specific choice with the newer ADC, and we have liso-cel too, but it’s a category 2B recommendation. So we’re thinking about it much earlier in the game these days, either for second-line therapy if the patient has refractory disease or early relapse, or for third-line therapy if they could or couldn’t go to transplant or had that relapse after transplant a while ago.1

There’s some debate on whether, if a patient had second-line therapy, they need to do anything after that for consolidation. I don’t think we’re going to see a lot of allogeneic transplants done in the future for lymphomas—for B-cell lymphomas at least. We have so many other options that...work, so that’s going to be a rare niche consideration. The transplant center and CAR T-cell center, which presumably overlap, would say whether there’s any reason to consider it, but often we do have CAR T-cell therapy as a third-line option.

The patient did have R-CHOP…then we’re going to go on to CAR T-cell therapy after that. If they had their salvage and transplant and still relapsed 1 year after that or 6 months, we are going to put CAR T-cell therapy up near the top of the list. The 3 CAR T-cell therapies are axi-cel, liso-cel, and tisagenlecleucel [tisa-cel, Kymriah]. We also have the ADC loncastuximab tesirine [Zynlonta] and in theory we could also use selinexor [Xpovio], although it is not an option yet at this point.1

What is the mechanism of action of polatuzumab vedotin?

Polatuzumab is a classic ADC. It’s partnered with the same MMAE [monomethyl auristatin E] that’s on brentuximab, which [can be used] maybe in stage III or IV Hodgkin’s lymphoma as part of the A-AVD [brentuximab vedotin, doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine] regimen. It’s the same payload, so I wouldn’t expect to have a lot of difference in terms of adverse events [AEs].

But it is against a very unusual target that we didn’t deal with much before. The CD79b transmembrane molecules are linked with the B-cell receptor and transmit signals internally in the cellular machinery. So polatuzumab binds to CD79b and then is pinocytosed into the cell into an endosome lysosome where the individual enzymes in that lysosome dissolve the linker that holds the chemotherapy to the antibody. It’s that smart-bomb approach of bringing it to the cell of interest and that releases the chemotherapy only inside the cell once the MMAE is cleaved from the antibody. So, it is a vincristine-like drug. It inhibits tubulin polymerization and causes growth arrest and apoptosis, so it kills the cell from the inside out using the smart-bomb approach.2

Which trial supports the use of pola-BR in patients with refractory or relapsed DLBCL?

There was a phase 2 randomized controlled trial of pola-BR for refractory or relapsed DLBCL [NCT02257567]. Patients had to have at least 1 line of therapy, reasonable performance status, and no severe peripheral neuropathy, because much like brentuximab, one of the AEs of polatuzumab is peripheral neuropathy. These were patients who were not planning or couldn’t go on to transplant or already had failed one.

The investigators did a safety run-in of the triplet with half a dozen patients first; then they went into the randomized phase of BR vs pola-BR, which had 40 patients on each arm. Once they established that it was effective and safe, they expanded the pola-BR arm with 106 more patients [pooled pola-BR cohort, n = 152]. Patients received about 6 cycles or so of pola-BR with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for neutropenia prophylaxis.3,4

The trial had a pretty good distribution of patients. About 80% or more of these patients had less than 12 months of remission from their previous treatment. Several patients had multiple lines of prior therapy. In fact, up to 45% or so had had 3 lines or more.

Many of these patients had been refractory to that last line of therapy with either no complete response or early relapse, and just a smattering of patients had previous stem cell transplant. So, it was well distributed with maybe a little more frequency of the non–GCB DLBCL, which would be expected. They were a bit more likely to relapse and come to a trial like this.4

What was the efficacy observed for patients in this trial?

The overall response rate [ORR] by the investigational review committee was 42.5% in the main pola-BR arm, which was randomized against BR. The other 106 patients in the extension group who were just getting the triplet combination held that same response of 41.5%, with 38.7% of those being complete remissions.4

The durability of this response in terms of progression-free survival [PFS] throughout the first year and beyond was superior in the pola-BR arm compared with BR. At the 2-year time point, approximately 28% of the patients on the triplet combination were still in remission and only 9% of the patients were still in remission from BR, so less than 10%. Most of that drop-off is right in the beginning, the first 2 months.

The 2-year time point has the widest gap between the arms, and then they seem to almost plateau out past 2 years. But there is a clear advantage in the PFS for the pola-BR arm. This translated into an overall survival [OS] benefit as well, plateauing at about a 2-year OS of 38% in the pola-BR group and 17% in the BR arm.

The pooled patients treated with pola-BR were 152 if you add the safety run-in, randomized part, plus the extension group. A few went on to transplants [4 patients]. A few more went on to CAR T-cell therapy [9 patients]. Patients who went on to CAR T-cell therapy afterward had 12 to 28 months’ improvement in survival. One patient had the pola-BR for bridging to their CAR T-cell therapy, and 4 out of those 9 patients who took CAR T-cell therapy afterward are alive and remain in follow-up.

REFERENCES

NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. B-cell lymphomas, version 2.2023. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://bit.ly/3YHJVB7

Sawalha Y, Maddocks K. Profile of polatuzumab vedotin in the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a brief report on the emerging clinical data. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:5123-5133. doi:10.2147/OTT.S219449

Sehn LH, Herrera AF, Flowers CR, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(2):155-165. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00172

Sehn LH, Hertzberg M, Opat S, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin plus bendamustine and rituximab in relapsed/refractory DLBCL: survival update and new extension cohort data. Blood Adv. 2022;6(2):533-543. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005794