Mesa Discusses Treating Myelofibrosis and Other MPNs

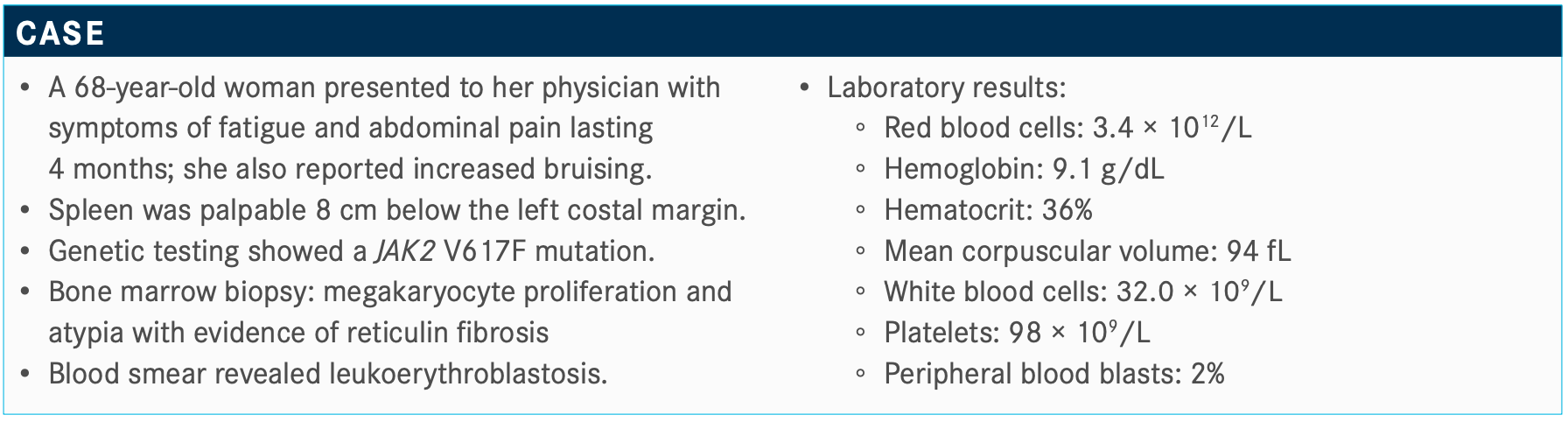

Ruben Mesa, MD, reviewed a case of a 68-year-old woman with a myeloproliferative neoplasm, during a virtual Case Based Peer Perspectives event.

Ruben Mesa, MD

Ruben Mesa, MD, director, Mays Cancer Center at The University of Texas Health San Antonio, MD Anderson Cancer Center San Antonio, TX, reviewed a case of a 68-year-old woman with a myeloproliferative neoplasm, during a virtual Case Based Peer Perspectives event.

Targeted Oncology: What type of testing would you perform on this patient? Are there certain mutations in particular that you are looking for?

MESA: The NGS [next-generation sequencing] panels are helpful. In myelofibrosis, they’re the most necessary in the potential transplant candidate [who is] of intermediate risk [and for whom] you’re uncertain of the [prognosis]. In patients who are high risk, it’s also useful information. If someone hasoverwhelmingly high-risk disease, they’re not going to be at higher risk [based on these results], but I think it’s helpful information that we continue to learn about in terms of clonal evolution. Or, if they go to transplant, we know what the clones look like at the onset prior to undertaking [the trans- plant]. Our medical therapies have not resolved these muta- tions, but of course that could change. It’s helpful information for us to know.

There are bad actors like ASXL1, EZH1/2, [and] the IDH1 muta- tions. The absence of a bunch of these somatic mutations is somewhat reassuring. It’s helpful in combination with the clini- cal data. How are they feeling as far as their spleen, cytopenias, etcetera? There are [many] of these models that have been created, and some of which now have genetic data only. That’s probably incomplete. I can put the stained clone in 2 different patients, but if one is 45 years old and healthy and the other is 70 years old with comorbidities, there’s no way those patients are doing the same. I think the clone is important, but the clone always has to live in a person.

Which risk-assessment tool do you use most often?

MIPSS [Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System] is the most popular, and it has a couple of advantages. One is that it has its own website; you can Google it and book- mark it on your computer. I always tell my trainees, don’t bother to memorize any prognostic score in terms of how to calculate it because we have [a] calculator. But have a sense of what...the biological [characteristics are] that make a difference in terms of the prognosis for patients that give you some insight into the behavior of the disease. Have a sense of where and when that [is] useful.

There have been multiple models that have been validated. They help to stratify patients in terms of their outcomes in a range of ways. They are largely surrogates [of transformation to acute myeloid leukemia] as well, although it’s a different issue. The outcome for the patient with myelofibrosis if they pass away from the disease—which is still the majority of patients—is [that] they either die of progressive features of myelofibrosis, which can include progressive debilitation, cytopenias, and a range of complications related to that, or they progress to acute leuke- mia and can pass away from those sets of difficulty.

Why are prognostic models referenced in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines?

I was involved with the original NCCN guidelines for MPNs [myeloproliferative neoplasms].1 Originally, we had the prog- nostic score, or at that point the DIPSS [Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System] or the DIPSS-Plus...to help stratify who’s lower risk or who’s higher risk in terms of therapy to get rid of some of the granularity.

Would you consider transplant in this case?

I have had patients who have done well with transplant. Transplant can be curative, but we can also wait too long, partic- ularly in the setting of myelofibrosis. I think when it’s being used as salvage therapy in myelofibrosis, the outcomes are less [successful] than we would like. In my estimation, the best time to have a transplant is probably before either the patient or physician really feels the patient needs one. It’s during their optimal JAK inhibitor response that they probably do the best. Now, on the flip side, that’s the time that they have the most to lose in that their quality of life is good and they’re stable. It’s a difficult decision.

Which systemic therapies might you consider in this patient?

In terms of medical therapy, we now have 2 approved ther- apies in the front line, both ruxolitinib [Jakafi] and fedratinib [Inrebic], and many others in development that were discussed at the ASCO [American Society of Clinical Oncology] Annual Meeting and at the 25th Annual Congress of EHA [European Hematology Association].

Ruxolitinib has now been approved for a long time with data from the randomized studies—now almost historical in nature— with the COMFORT studies, both COMFORT-I [NCT00952289] and COMFORT-II [NCT00934544]. It showed for the first time in randomized settings a drug that was effective in myelofibrosis. Ruxolitinib was clearly better than placebo [and best alternative therapy] in the COMFORT-I study that Srdan Verstovsek, MD, PhD, and I led, and which was a European study.2

That was relevant because at the time the standard of care was Hydrea [hydroxyurea]. We recognized in retrospect that hydroxyurea is not as great a therapy for myelofibrosis. It’s good therapy for ET [essential thrombocytopenia]. It helps to control platelets reasonably well in many, but it’s not a perfect drug. In polycythemia vera, it’s a reasonable frontline therapy, although interferon may have advantages. In myelofibrosis, it might help with leukocytosis but doesn’t do much for splenomegaly symp- toms, anemia, fibrosis, or progression toward acute leukemia.

Would you send her for transplant, start ruxolitinib or fedratinib, observation, or something else?

I’ll remind [you that] this patient is 68 years old, has a big spleen, has a JAK2 mutation, and leukoerythroblastosis...most physicians would start her on ruxolitinib. That would surely be consistent with our NCCN guidelines.1 Some would refer [her] for stem cell transplant. That would not be incorrect. She has some higher- risk features. She has anemia, 2% [peripheral blood] blasts, and mild thrombocytopenia. In all honesty, some of these things we do in parallel.

I don’t typically [rely on transplant], but I do send patients who are potentially eligible to visit with a transplant physician so that that process can start. The patient can learn more about the process. We could see what a potential donor solution would be. We could see what sort of initial response to therapy that they have. Patients who go to transplant would likely start JAK inhibi- tion before they would go [for their transplant]. Even if they found a good sibling match, and the patient wants to go through with that, it’s probably going to take 3 to 4 months and they can be on JAK inhibition before that. They might have a better outcome with the spleen being smaller and going to transplant better. [It’s] a bit of an artificial question in that you might choose to do more than one of these things in parallel.

What are the advantages of JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib?

There are patients from the phase 1 study of ruxolitinib at our centers that are still on the therapy. These are individuals that had expected survival [times] of under 3 years. I think that patients that are having a great response to JAK inhibition have their natural history improved. Splenomegaly symptoms were both clinically meaningful [and measurable according to early ruxolitinib activity].

Every time we’ve looked at it, there is an indication that ruxoli- tinib improves survival for patients. Now, the studies were not survival studies in their design, and that was for a variety of reasons. It would have been largely unethical and unrealistic to expect patients to stay on placebo forever so that they could do worse on a control arm [to prove] survival advantage. Having been involved with caring for patients with myelofibrosis before JAK inhibitors and after, there’s no question that these drugs improve survival. I’d say that the rate by which patients passed away...has decreased significantly over the past decade as opposed to my first 15 years of treating myelofibrosis. [Ruxolitinib] does not cure the disease, and it’s not [successful] in every patient. I don’t think we yet truly know why we see that difference.

Why is the spleen response with ruxolitinib so important?

I do not believe...that shrinking the spleen because of its mechan- ical effect leads to an improvement in survival. However, the spleen is a good barometer of the quality of JAK inhibitor response, and responding to JAK inhibitors improves survival. I think tracking this thing is important, not just because it shrinks but because it means that whatever benefit we’re getting from JAK inhibition is present.

What is the optimal dose of ruxolitinib in this patient population?

We’ve learned several things over time, including the issue of dosing, as it relates to efficacy and survival. Patients probably need to be on 10 mg twice a day or more to be getting the optimal benefit. Ideally, [we should be] getting them to 15 mg twice a day, or, if reasonable, 20 mg twice a day. There is contro- versy. My colleague...strongly believes we should start everyone at the higher dose. I think it’s OK to start lower, but you must accelerate the dose. There are likely too many patients out there on a suboptimal dose of ruxolitinib. Starting with those doses is fine, but rapidly increasing the dose where you truly see a signif- icant reduction in the size of the spleen and improvement in the symptoms [is necessary]. If you’re not achieving that, then that is when it’s important to think about second-line therapy, dose adjustments, or a clinical trial.

What adverse effects (AEs) of ruxolitinib are there that treating physicians should be concerned with?

In terms of toxicities, there are issues of cytopenias. In the phase 1 studies, it was thrombocytopenia that was the dose-limiting toxicity. Anemia is the most functional difficulty in that the throm- bocytopenia is present, but it usually is not the driver in terms of limiting your dose.

When would you choose to use fedratinib?

Since last September, we have the approval of fedratinib as well for these patients.3 It was supported by the phase 3 JAKARTA study [NCT01437787], a randomization between fedratinib at 2 different dose levels versus placebo in patients that had intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis. The timing of the trial overlapped with the period before ruxolitinib was approved.

There was a nice response in terms of splenomegaly compared with placebo. There was a 500-mg arm that performed reasonably well in terms of efficacy but had more toxicity, so the approved dose is 400 mg.

In terms of toxicity, there are gastrointestinal toxicities. Typically, patients are [given] prophylaxis with antidiarrheals and antinausea drugs. I’d have to say most patients don’t tend to have a lot of difficulties with that. They can have cytopenias; there [are] no direct head-to-head data between fedratinib and ruxolitinib in terms of rates of cytopenias, but it’s not clear that there is necessarily a clear advantage between one or the other.

What does the black box warning say for encephalopathy in patients who receive fedratinib?

It was recognized that there were several cases of individuals who had had some degree of CNS [central nervous system] toxicity in 8 cases out of about the 900 patients that were treated. It was suspected that it was Wernicke encephalopathy. The drug was put on a clinical hold. Those cases were subsequently looked at in great detail by neurologists and others, and what was seen was that there was a rare CNS-confusion episode that did occur. It was only clear that 1 of the patients met the criteria of having Wernicke encephalopathy, but they likely had [that] when they were enrolled in the study. In addition, the Wernickes may have been worsened because this patient, at the 500-mg dose, did have a lot of nausea and vomiting.4

With an abundance of caution the drug was approved, but with a black box warning [cautioning physicians to] measure thiamine, replace thiamine if need be, and monitor for Wernicke [enceph- alopathy]. Having prescribed it after its approval, [I have found that] it’s not a major limiting factor, but just something to be mindful of and exercise every caution.

References

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Myeloproliferative neoplasms, version 1.2020. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/ physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf

2. Mesa RA, Kiladjian JJ, Verstovsek S, et al. Comparison of placebo and best available therapy for the treatment of myelofibrosis in the phase 3 COMFORT studies. Haematologica. 2014;99(2):292-298. doi:10.3324/haematol.2013.087650

3. FDA approves fedratinib for myelofibrosis. FDA. August 16, 2019. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/ fda-approves-fedratinib-myelofibrosis

4. Mullally A, Hood J, Harrison C, Mesa R. Fedratinib in myelofibrosis. Blood Adv. 2020;4(8):1792-1800. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000954