Gasparetto Reviews Data for Selinexor Combination Regimen in R/R Multiple Myeloma

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable event, Cristina Gasparetto, MD, discussed the case of a patient with stage I multiple myeloma and highlighted outcomes of the phase 3 BOSTON trial.

Cristina Gasparetto, MD

Director of the Multiple Myeloma Program

Professor of Medicine

Duke University School of Medicine

Durham, NC

CASE SUMMARY:

• A 70-year-old White woman was diagnosed with stage I multiple myeloma.

• Medical history: stage 3 chronic kidney disease and mild renal impairment

• Fluorescence in situ hybridization showed a 17p deletion (del[17p]) alteration.

• The patient declined autologous stem cell transplant.

• She received lenalidomide (Revlimid), bortezomib (Velcade), and dexamethasone and had a best response of very good partial response. She continued lenalidomide maintenance.

• Two years later: On routine follow-up, the patient reported mild fatigue.

• Bone marrow plasma cells, light chains, and M protein were rising, and kidney function was worsening (now stage IV chronic kidney disease).

• The patient received daratumumab (Darzalex), pomalidomide (Pomalyst), and dexamethasone and had a best response of very good partial response.

• One year later, a second relapse was discovered; kidney function continues to decline.

Q: What were the outcomes of the phase 3 BOSTON study (NCT03110562)?

GASPARETTO: The BOSTON study was a randomized study designed to test the combination of selinexor [Xpovio], bortezomib, and dexamethasone vs bortezomib and dexamethasone. And very importantly, in the study arm with the triplet combination, the bortezomib was given only once a week, on days 1, 8, 15, and 221—this is very important because bortezomib is approved for biweekly use2—and in the control arm, bortezomib was delivered twice a week on days 1, 4, 8, and 11.1 But a lot of us are using bortezomib weekly, for convenience and to reduce some of the potential toxicity.

The study was designed to address the big question: Can we use less bortezomib and decrease the rate of toxicity but still have an eff ective regimen in combination with weekly selinexor (given at a dosage of 100 mg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22, and also on day 29). The dexamethasone was given at a dosage of 20 mg on the day of and on the day after bortezomib; [patients in the triplet arm received additional doses of dexamethasone on days 29 and 30]. The patients in the control arm received more dexamethasone and more bortezomib overall because on the study arm, patients received a 40% lower bortezomib dose and a 25% lower dexamethasone dose [after 24 weeks].1

Four hundred patients enrolled, with a median age of 67 years. There was a fair number of patients [older than] 65 and [75] years as well. The primary end point was progression-free survival [PFS]; overall response rate [ORR] and depth of response were secondary end points. Another very important secondary end point was peripheral neuropathy of grade 2 or greater. Overall survival [OS], duration of response [DOR], and safety were other secondary end points.1

I always like to dissect the data regarding the patient characteristics. There was a fair number of patients, about 20% in each group, who were older than 75 years. This is very important because we are dealing with different patients, patients [of different ages or] with a lot of comorbidities. The percentage of patients with del(17p) was about 10% in each arm. Also included in the high-risk cytogenetic analysis were [translocation] t(4;14) and the 1q21 amplification.1 The latter is very important because the 1q21 amplification is becoming a focus of attention, particularly when combined with other high-risk genetics.

There was a fair number of patients who had received 1 previous line of therapy [approximately 50%], 2 prior lines [approximately 30%], and 3 prior lines [16% in the triplet arm and 20% in the control arm], and a low percentage of patients who progressed on daratumumab [6% and 3%, respectively], which is also an important population of patients because patients refractory to daratumumab have a more difficult time with the subsequent line of therapy.

The majority of patients [approximately 70%] were [previously] exposed to bortezomib, but some were exposed to carfilzomib [Kyprolis; 10% in each arm] or to lenalidomide [approximately 40%], and a small percentage were exposed to pomalidomide.1

The primary end point of this study was PFS, which was met with a median PFS of almost 14 months in the triplet arm, despite the fact that bortezomib was given only once a week, vs 9.46 months for the control arm [HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53-0.93; P = .0075].1

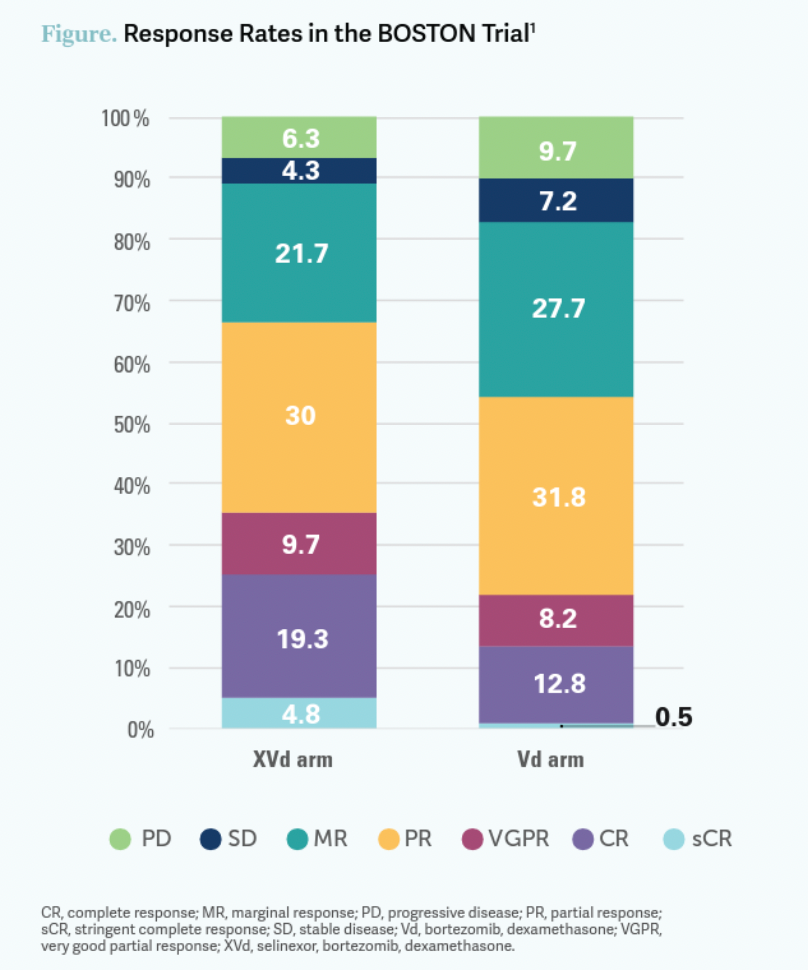

The ORR was [76.4%] in the experimental arm and [62.3%] in the control arm [Figure].1 The median time to response was a little more than 1 month [1.1 months vs 1.4 months, respectively], and the median DOR was [20.3 months vs 12.9 months, respectively].1

Q: What were the results of the subgroup analysis?

For all different subgroups, the PFS was superior with the addition of selinexor, even in the older populations and in frail patients. The patients who were refractory to daratumumab performed well. Patients who had high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, such as del(17p), [although] the numbers were small, did quite well. The patients with the 1q21 amplification also did well with the addition of selinexor. And importantly, so did the patients with renal compromise.1

In [multiple myeloma], we want to know that the patients with high-risk cytogenetics are performing well; there was no doubt that with the addition of selinexor and the proteasome inhibitor, the patients with high-risk cytogenetics had an improvement of PFS [12.91 months vs 8.61 months in the experimental and control arms, respectively]. This benefit was also observed in the patients with standard-risk cytogenetics [16.62 months vs 9.46 months, respectively]. The median OS was about the same [between the arms] among those with high-risk cytogenetics and was not reached in either arm among patients with standard-risk cytogenetics.3

The responses were similar or maybe a little better with the addition of selinexor, but the DOR was definitely much longer [overall].1,3 The patients with renal impairment who had an estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] of less than 40 mL/ min also had an improvement of median PFS with the addition of selinexor compared with the control arm at [7.62 months vs 4.30 months, respectively]. Among patients with an eGFR of 40 mL/ min to 60 mL/min, again the addition of selinexor was beneficial [median PFS, 16.62 months vs 7.62 months, respectively], and of course in the patients with normal renal function, there was also an improvement in the PFS [13.24 months vs 9.66 months, respectively].4

Q: What adverse events (AEs) were observed in the BOSTON study?

I always like to divide the toxicity of selinexor into 3 groups: constitutional toxicity (eg, profound fatigue), gastrointestinal toxicity (eg, nausea, decreased appetite, weight loss), and myelosuppression. You have to pay particular attention to the thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia.1 When selinexor was first approved for late-line therapy in combination with dexamethasone, it was given twice a week, and it was very diffi cult to sustain therapy.5

[We] realized that when selinexor is given in combination, we really don’t need to go with a higher dose, and selinexor, when given in all the combinations, is given only once a week.6 In my opinion, it’s a different drug. The toxicity that we see when we deliver selinexor once a week is the same toxicity, but it is definitely mitigated by the dosage. The dose modifications are important to decrease the toxicity. Of course, aggressive supportive care is important from the very beginning.1 [The weight loss] occurs during the first month or maybe 2 months, but then it seems to go back to baseline, and we recommend that you monitor the body weight and the nutritional status of the patient.

We have a dietitian meet with patients at the beginning of the regimen and review some diff erent types of supplementation. In my opinion, if your patient is responding and you’re controlling the nausea, the patient should be able to sustain therapy.

Q: How did the toxicity profiles of the STORM (NCT02336815) and BOSTON studies compare?

During the STORM study when the selinexor was given at a higher dose twice a week [80 mg biweekly, 160 mg total], some of the adverse events were very pronounced, and it was very diffi cult to sustain therapy.7 But given once a week [at 100 mg], it’s definitely a different drug and much more manageable, and it could be used more often because it is an eff ective drug.1

[The STORM study] had a more heavily pretreated population of patients, with a median of 7 prior lines of therapy vs only 2 in the BOSTON study, and [the rates of grade 3 or 4 toxicities tended to differ between the studies]. Thrombocytopenia affected [58%] vs [39%] of the populations treated with the STORM and BOSTON regimens, respectively.

The rates of neutropenia were [21% and 9%, respectively]. Nausea affected 10% vs 8%, respectively, so it was about the same. The rate of fatigue decreased with the weekly administration, [affecting 25% vs 13%, respectively], as did the hyponatremia, [affecting 22% vs 14%, respectively].1,7

Q: What are the dosing modification guidelines for selinexor?

In the BOSTON study, a very high percentage of patients required dose modifi cations. The recommendation is to go down [from 100 mg] to 80 mg, then to 60 mg, [and] then to 40 mg.6 I had some patients on 40 mg once a week. And then you may consider permanent discontinuation.6 I have to say that I have had some patients go down to 20 mg.

Q: What clinical outcomes have been observed following dose reduction?

The median PFS of patients who required dose reduction was actually better than for patients who were able to sustain selinexor without that modifi cation [16.6 months vs 9.2 months, respectively]. Also, the response improved with the dose modification [very good partial response observed in 81.7% vs 66.7% of patients, respectively], mainly because the patients were able to sustain therapy for a prolonged period of time without skipping a dose.8

It doesn’t absolutely make sense because the patients without dose reduction had to stop therapy sooner for other reasons, but I think [these results are the effect of] the sustainability of the therapy for a prolonged period of time. If you make the proper dose adjustment, you’ll see patients able to do the therapy for a prolonged period of time. That’s what I think, based on my experience.

REFERENCES

1. Grosicki S, Simonova M, Spicka I, et al. Once-per-week selinexor, bortezomib, and dexamethasone versus twice-per-week bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma (BOSTON): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10262):1563-1573. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32292-3

2. Velcade. Prescribing information. Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; 2022. Accessed May 6, 2023. https://bit.ly/42qmDRz

3. Richard S, Chari A, Delimpasi S, et al. Selinexor, bortezomib, and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone in previously treated multiple myeloma: outcomes by cytogenetic risk. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(9):1120-1130. doi:10.1002/ajh.26261

4. Delimpasi S, Mateos MV, Auner HW, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of once-weekly selinexor, bortezomib, and dexamethasone in comparison with standard twice-weekly bortezomib and dexamethasone in previously treated multiple myeloma with renal impairment: subgroup analysis from the BOSTON study. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(3):E83-E86. doi:10.1002/ajh.26434

5. FDA grants accelerated approval to selinexor for multiple myeloma. FDA. Updated July 3, 2019. Accessed May 7, 2023. http://bit.ly/3WWQzn6

6. Xpovio. Prescribing information. Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc; 2020. Accessed May 7, 2023. https://bit.ly/3FArFSR

7. Chari A, Vogl DT, Gavriatopoulou M, et al. Oral selinexor-dexamethasone for triple-class refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(8):727-738. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1903455

8. Jagannath S, Facon T, Badros A, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients (pts) with dose reduction of selinexor in combination with bortezomib, and dexamethasone (XVd) in previously treated multiple myeloma from the BOSTON study. Blood. 2021;138(Supplement 1):3793. doi:10.1182/blood-2021-146003

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More