Roundtable Discussion: Socinski and Participants Review Chemotherapy and EGFR Inhibition in NSCLC

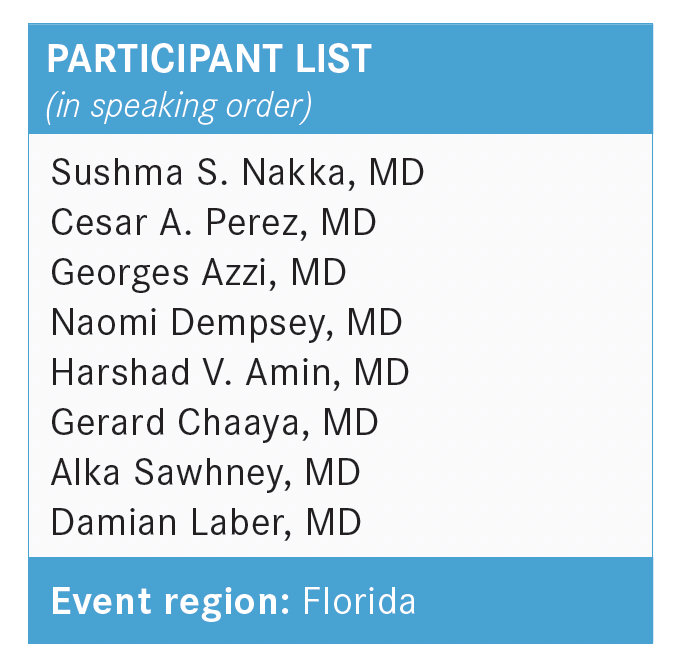

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable event, Mark A. Socinski, MD, led a discussion about treatment of patients with EGFR-mutant non–small cell lung cancer.

Mark A. Socinski, MD

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable event, Mark A. Socinski, MD, executive medical director, AdventHealth Cancer Institute and member, Thoracic Oncology Program in Orlando, FL, led a discussion about treatment of patients with EGFR-mutant non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

SOCINSKI: For those who are both testing and not testing, what are the challenges and barriers to testing?

In my institution, our pathologists do a ton of reflex testing, so from my perspective, there are not a lot of challenges [or] barriers when you’re doing it reflexively, but that may not be true in all centers.

NAKKA: In our pathology department, we get a basic lung panel without asking.

SOCINSKI: Is that OK with you? Can you share what’s in the panel?

NAKKA: Yes, it’s all right. Just a regular EGFR [test].

SOCINSKI: Do the pathologists do that reflexively, so you don’t have to order anything?

NAKKA: Not the initial time, yes.

SOCINSKI: Yes, this addresses the multidisciplinary team, in terms of who orders [tests].

PEREZ: Ordering has become a little easier in our practice…we order next-generation sequencing [NGS] for all patients. It’s become a little easier, with fewer payer limitations, and we have to order it in the early stage.

AZZI: In terms of payers, [in my experience], there’s no coverage for early stage. If you want to do a full NGS panel, that’s not going to get paid if it’s not stage III or IV.

PEREZ: We get the result. There are not a lot of issues, and the patients don’t get a bill, so we [can] still order it.

AZZI: There should be lobbying to change the Medicare rules for lung cancer, at least, [because] we know [we will need testing for EGFR], maybe ALK, and other alterations in the future. Maybe they need to cover earlier stages for NGS testing.

SOCINSKI: The points being made are pertinent. Patients without a significant history of smoking who are women have a reasonable chance of having an EGFR mutation. Beyond that, one of my concerns is that, in metastatic disease, we now have 9 or 10 actionable alterations.

We even have a KRAS drug, as of recently. So our testing is NGS, broad-based panels, and these sorts of things—can you justify that? Or should we be going back to the old days when we used to do single-gene testing? Should that be the standard of care?

If your pathologists are complaining about the cost of things, should we be thinking about that—realizing many of the early-stage patients are going to become late-stage patients because they recur?

PEREZ: Even back in the day, before the late-stage NGS was approved, we were already doing it....So that’s where we’re eventually going.

Anyhow, we can use the single gene, but we know this is just a matter of time before more effective inhibitors will also show benefit for early-stage disease. [We were doing testing in] lung cancer before it was FDA approved. That’s my point.

DEMPSEY: You’re going to run the risk of exhausting your tissue if you’re just doing in-sequence single mutation testing. If you’re removing a 5.5-cm tumor, you’re not too worried about how much tissue you have, but that can be a concern when you just have a biopsy.

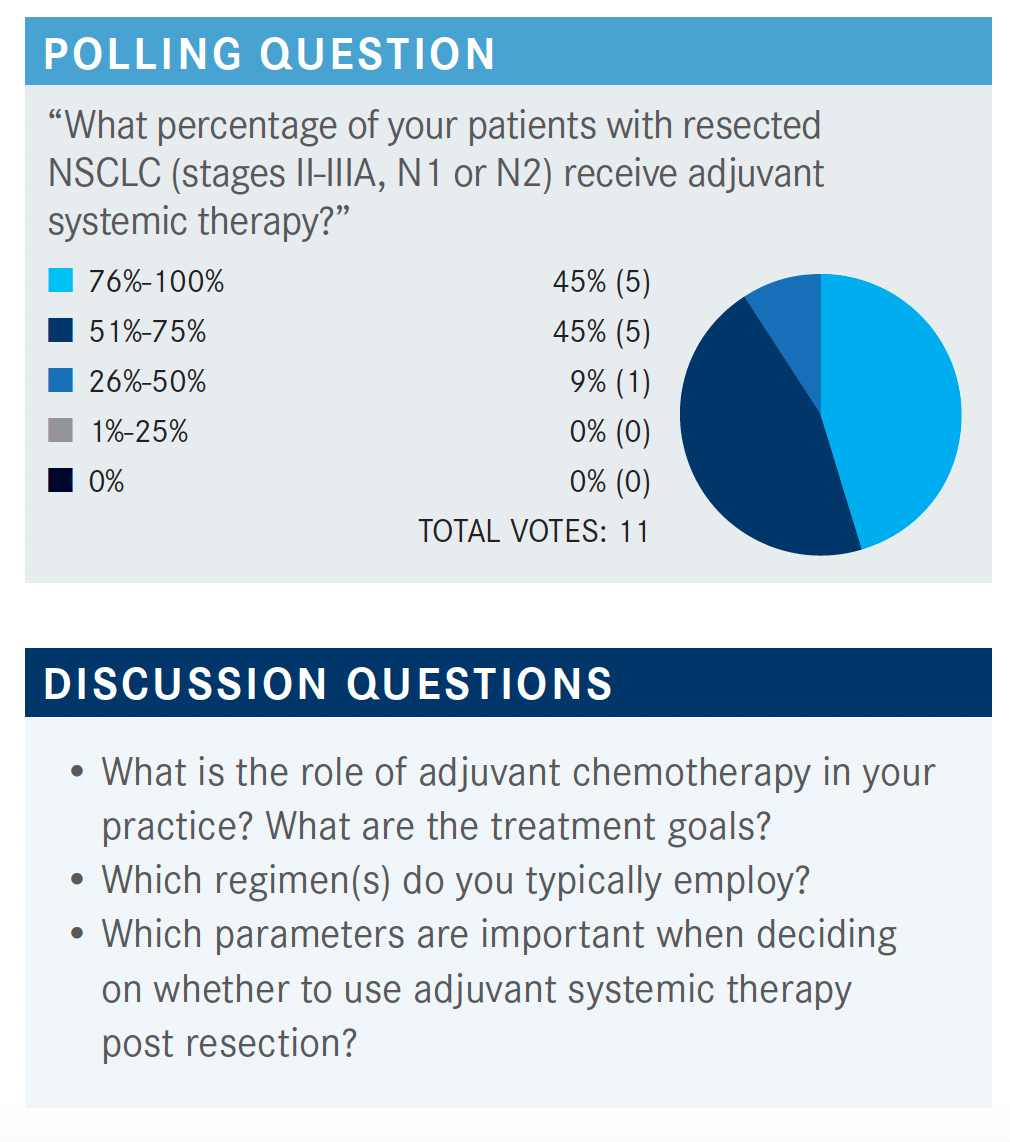

SOCINSKI: It seems like most of you are doing it, so I figure the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in your practices is well established. Why are you doing it and which chemotherapy do you use? I try to always use cisplatin vs carboplatin, and the only choice I have is the second drug I’m going to use in patients with nonsquamous [histology] vs the second drug I’m going to use [ for squamous histology].

NAKKA: In the adjuvant setting, I explain we are reducing the risk of recurrence, and I typically use carboplatin/ paclitaxel. In some cases, where I have an adenocarcinoma, I use cisplatin/pemetrexed [Alimta]. [In some cases], I have used carboplatin/gemcitabine if there was an allergic reaction to paclitaxel.

AMIN: I agree. The reason to use [1] is to reduce the recurrent risk about 30% to 35%. I use carboplatin/ pemetrexed or cisplatin/pemetrexed, depending on the patient performance status. I prefer to use cisplatin if I could. Otherwise, I compromise with carboplatin/pemetrexed [for] adenocarcinoma and use carboplatin/paclitaxel, cisplatin/paclitaxel, or gemcitabine/carboplatin in patients with squamous histology.

SOCINSKI: Is anyone out there using cisplatin/vinorelbine, which is certainly the most evidence-based regimen? I don’t use it. I think it’s a nasty regimen. Is anyone out there sticking with the evidence and using cisplatin and vinorelbine? Well, we can assume everyone is trying to use cisplatin if they can, but they realize that may not be possible in every patient. It seems like there’s an affinity for pemetrexed-based therapy in the adenocarcinomas, then either a taxane or gemcitabine in the squamous tumors. Do things like histology, certain factors of histology—lymphovascular invasion, pleural invasion, degree of differentiation—impact how likely you are to use it in the node-negative patients? Is age an issue? How do you talk to these patients about adjuvant therapy? What do you tell them [about] how much benefit they are going to get?

DEMPSEY: For me, the decision between cisplatin vs paclitaxel comes down to the last few [factors]. I prefer to use cisplatin, but if I think the performance status is borderline, if they’ve had a real tough recovery from their surgery, renal issues, [and] age will tip me over into using paclitaxel. [For me], pemetrexed vs paclitaxel is histological. I don’t make that decision based on any of the other factors, such as nodal status, visceral invasion, or anything like that.

CHAAYA: I will [decide] based on the risk features. If someone has high-risk features, I’ll give them chemotherapy. If not, I wouldn’t. When I talk about high-risk features, I mean tumor size more than 4 cm and visceral/pleural involvement, but we’re not talking about lymph nodes, and I take that into account for a high-risk patient.

SOCINSKI: How do you portray the benefit? When you look at the meta-analysis, the absolute benefit at 5 years is 5%.1 The relative benefit based on [overall survival (OS)] hazard ratios in the node-positive patients, the hazard ratio is about 0.8, so it’s a 20% risk reduction. In the node-negative population, in the meta-analysis, it’s not significant. The hazard ratio is about 0.86. At best, it’s a 14% reduction in the risk of death. When you start to calculate what that absolute difference is, if you have N1 disease and a small primary [tumor]—let’s say your chance of surgical cure is 50% to 60% and your risk reduction is 20%, you’re talking about improving your cure rate from 50% to 60% to 64% to 68%. It’s not 100%.

Do you have those conversations with your patients? What sort of details do you talk about? Because you’re having these same conversations with patients with breast cancer and patients with colon cancer, I assume, but is it the same conversation you’re having with patients with lung cancer?

PEREZ: The data from the ANITA trial [ISRCTN 95053737] mentions several things.…It’s hard to justify adjuvant chemotherapy in a patient with a 4.5-cm tumor with no lymph nodes, and even with a couple risk factors, because the 5-year benefit [may be] something between 4% and 5%, if anything. When we have honest conversations with patients, we explain to them there is a 95% chance this chemotherapy will do nothing to them, that it’s the absolute benefit. Then most patients will say no, but it depends on how we explain to the patient.

That’s one of the failures of the platinum [therapy]— that it is so much toxicity with so little benefit for them. When we’re honest with that opinion when treating lymph node–positive disease, or a 7- to 8-cm tumor with visceral invasion, that’s a completely different scenario. But with anything less than 5 cm, even with young patients, it’s very difficult. If you do convince them, maybe you were not honest.

SOCINSKI: Yes, I suspect the lung cancer population may be different from, say, the breast cancer population. [That’s my impression], at least. Full disclosure, I haven’t seen a patient with breast cancer since 1992, but it seems to me the breast cancer population is willing to take much more therapy for a smaller benefit than the lung cancer population is.

I find myself trying to make patients understand benefit, and they’ll say, “Doc, the bang just ain’t worth the buck at this point.” So they opt out of adjuvant chemotherapy once you truly make them understand what the reality is about the benefit.

Remember we’re talking about OS. This is a complicated [issue], and there are lots of issues in this population. I was just curious to see how often those issues are explored in an in-depth way with each postsurgical patient with lung cancer.

SAWHNEY: Patients who got chemotherapy benefited more from the osimertinib [Tagrisso]. Can you explain how that works?

SOCINSKI: I think it has to do with the fact that if you look at the percentage of patients with IIIA disease who got chemotherapy, it was significantly higher than the percentage of patients with IB disease who got chemotherapy. The magnitude of the benefit of the adjuvant osimertinib on disease-free survival [DFS] was increased going up in stage—much better benefit in the patients with stage IIIA vs stage IB. That observation may be more about the stage of the patient rather than whether they got chemotherapy.

SAWHNEY: Would you give chemotherapy to those patients if you already knew the EGFR status?

SOCINSKI: Yes, and the reason I would is that we know it’s modest, but we’re talking about an OS advantage vs a DFS advantage. So yes, particularly in the node-positive patients, adjuvant chemotherapy should be given. The question is: Are you going to pull the trigger for adjuvant osimertinib based on this significant DFS advantage?

[However], in a setting where cure is the goal, we don’t know that we’re going to cure more patients. Some have argued that maybe we’re just prolonging the inevitable, and what’s the answer to that? We think osimertinib is well tolerated, but remember that, once they recover from their surgery, they’re going back to work. They’ll be living their lives and doing normal things. They have no measurable cancer, and they have no cancer-related symptoms. A little bit of grade 1 or 2 diarrhea—try to go [to] work with grade 1 or 2 diarrhea every day, it’s no fun—or skin rash, or these sorts of things.

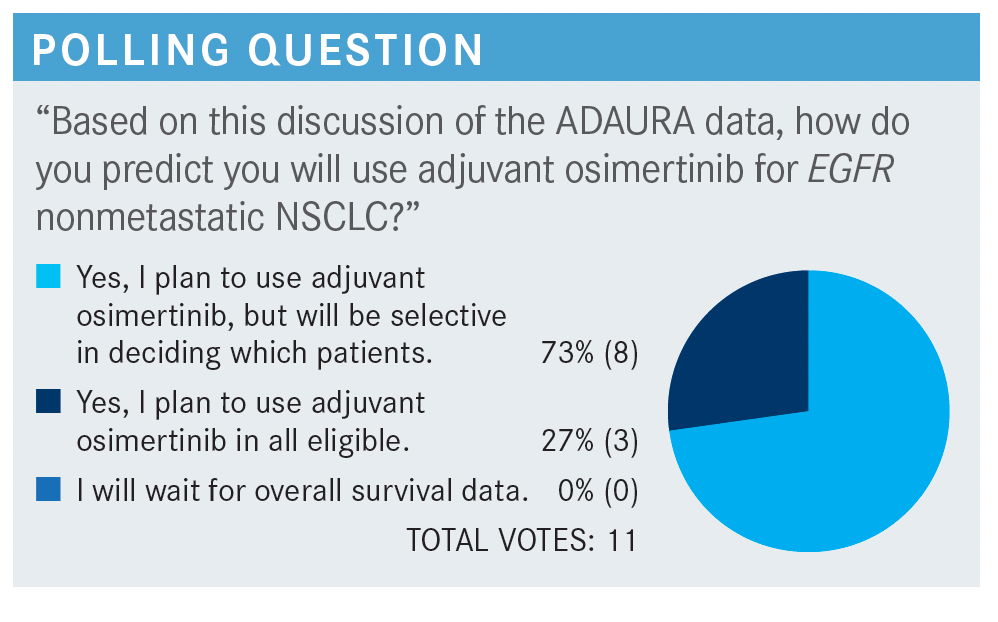

After seeing the ADAURA data, it’s all largely DFS. There are some very early OS data. Is this going to change your practice?

LABER: I think we’re back to the discussion of treat me now or treat me later because if you don’t give it in the adjuvant [setting], you’re going to use it when they have metastases. The advantage is you’re going to only treat the patients that needed to be treated, not 100% of the population. So, OS will be important to have before we can pull the trigger for using it in everybody.2

AMIN: I agree with that, although the FDA approved the drug based on DFS. To answer your initial question, this does not replace the need for adjuvant chemotherapy. We have OS data on that, especially in the patients with stage III disease. One can argue that maybe the chemotherapy benefit, or absolute benefit of chemotherapy, of adjuvant [therapy in a patient] with an EGFR mutation may be even better than somebody without an EGFR mutation. We didn’t have EGFR data of adjuvant chemotherapy when the study was done in the 1980s and 1990s. Adjuvant chemotherapy is indicated because we’re talking about OS benefits. You’re basically delaying the disease recurrence by putting the patient on osimertinib vs placebo. The benefit comes in at a higher stage because the placebo arm didn’t do better. [In] the osimertinib arm, whether patients had stage I disease or stage III disease, the pattern of recurrence is the same. So we’re basically delaying treating micrometastatic disease, whether it’s IB or III.

CHAAYA: In my opinion, it’s practice changing in stage III disease. For stage III, I would give chemotherapy followed by osimertinib if they’re EGFR mutation positive.

The major question I have is for stage II high risk after adjuvant chemotherapy. I’m not sure about the OS benefit in this case. The second thing I want to ask you is for stage II [but] not high risk. I don’t give them chemotherapy, but let’s say if they are EGFR positive, what would you do in this case?

SOCINSKI: I don’t have an answer for that. That’s an open question. You could debate it several ways. The CTONG trial [NCT01405079] was not designed as a noninferiority trial. Some physicians look at the CTONG trial and say, “At 5 years, the survival was the same, so why not give them adjuvant gefitinib [Iressa], osimertinib, or [something else] vs chemotherapy?” Well, the trial wasn’t designed as a noninferiority trial, so that question is [still] out there, and that was not answered. I don’t think we can use any of these trial data to say it’s OK to dismiss chemotherapy and just use adjuvant tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

In those patients, where you’re borderline, are you going to use chemotherapy or not? The best example is when there is a patient with a 4.5-cm [tumor] who is node negative, where the benefit is not entirely clear in that population. You say, “I don’t want to use chemotherapy, but I’m going to use adjuvant osimertinib.” I’m not quite sure that’s necessarily an evidence-based approach. Does that make sense to most?

CHAAYA: Yes, it makes sense to me. In the study, did they mention how many patients with EGFR mutations had PD-L1–positive expression? I don’t know whether this has an impact on the efficacy of osimertinib.

SOCINSKI: I don’t think we know that it does one way or the other. They didn’t report that, so in general, PD-L1 and EGFR-mutant population is [considered] less meaningful. Immunotherapy [IO], at least as monotherapy, doesn’t work very well. We don’t know about IO with chemotherapy

in this setting. The only thing we know is that IO with anti- VEGF therapy in EGFR-mutated disease seems to have an impact. That question is an important question because we have a series of IO adjuvant trials and neoadjuvant trials coming at us in the near future.

The questions [are]: How much testing do you do in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting? Are patients going to go down the IO route or the targeted therapy route? There are lots of issues and questions that need to be answered, but we’ll have to wait some time for data there.

SOCINSKI: So no one’s going to wait for OS. That’s interesting, even though that’s what we really want to know. Most of you will use it selectively, which is what I do. Not every patient is an ideal candidate for this. Or not every patient wants it, to be honest with you. About a quarter of you are going to use it in all patients eligible for the trial. When [most of] you said you’ll be selective, you’re looking at the stage as 1 of the variables, so I don’t want to address that. But what are you going to tell your patients about adjuvant osimertinib? Are you going to tell them it’s more likely to cure them, delay it, or [something else]?

NAKKA: It’s easier to sell for a stage IIIA patient to go on osimertinib than to give earlier-stage patients adjuvant osimertinib and commit them long term on osimertinib. For stage III patients, we’re already using the adjuvant durvalumab [Imfinzi] in a certain group of patients, so it’s not that hard to sell for a stage III patient.

PEREZ: Yes, some physicians would say we still don’t have the final data for the trial, but most people feel that, for advanced stage III disease, there probably will be an OS benefit. For stage II, we [must] be honest, and at the end, we let the patient decide whether they are willing to take 3 years of a treatment [for which] it’s unclear whether it will make them live longer or not.

REFERENCES

1. Artal Cortés Á, Calera Urquizu L, Hernando Cubero J. Adjuvant chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: state-of-the-art. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4(2):191-197. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2014.06.01

2. Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, et al; ADAURA Investigators. Osimertinib in resected EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(18):1711-1723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2027071

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More