Roundtable Discussion: Participants Discuss Treatment in Transplant-Ineligible DLBCL

Grzegorz S. Nowakowski, MD and Stephen D. Smith lead other participants of a Case Based Roundtable event in a discussion around treatment for patients with transplant-ineligible diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Grzegorz S. Nowakowski, MD

Grzegorz S. Nowakowski, MD and Stephen D. Smith lead other participants of a Case Based Roundtable event in a discussion around treatment for patients with transplant-ineligible diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

SMITH: By the time patients get to our center, they usually have committed the effort, the logistics, and the perception [regarding their being] a transplant candidate. But I think those issues may be more in the community. I’d really like to hear how other physicians think that aren’t located at a transplant center. But for us, [patients are ineligible for transplant because of] insufficient response to salvage [therapy], failure to collect [cells], or a lot of times accumulated toxicities during salvage treatment or during R-CHOP [rituximab (Rituxan), cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone]. They get 4 or 5 cycles of R-CHOP and they progress and/or get a significant infection. You wonder how appropriate it is to consider transplant.

Stephen D. Smith, MD

I think the toxicities from prior lines of chemotherapy also have a major influence. But I’d be curious about the perceptions of others with regard to desire to transpant. Is there an age cutoff that you all would consider as transplant-ineligible? Is it logistics or perception of treatment-related mortality? What would you say about maybe the top 2 reasons in your practice?

DY: I’m a community oncologist. I do my best to partner with the tertiary center and ours is also the University of Washington. I would refer the majority of my patients and let the transplant center make that decision. But I would say probably the easiest way to deem somebody ineligible for transplant would be the multiple comorbidities and the performance status. I wouldn’t necessarily have an age cutoff because there are a lot of good performance statuses in the elderly population. Then I let the transplant center decide most of the time.

GOLDBERG: I agree. I think we’re close enough to Seattle, so there’s no problem with the tertiary care and access issues. But comorbidities and performance status are usually the deciding point. A lot of them are obvious, but if someone’s on the borderline, we’ll still refer them up there for an opinion on whether it’s possible.

SMITH: We now have an explosion of drug approvals for patients who are transplant ineligible or at least after 2 prior lines. That and the advent of effective CAR [chimeric antigen receptor] T-cell therapies that changed the discussion around our historical KarMMa data [NCT03361748] around transplant. Patient preference has something to do with it, but we regard transplant as curative and we would like to give most patients a shot, if that’s a reasonable summary of what I’m hearing.

NOWAKOWSKI: Those are the patients who never achieve remission or relapse very close to the end of therapy.

SMITH: I think the number of truly refractory patients who really progressed during R-CHOP therapy is relatively low. I think the numbers—and this may be different than individual experiences—are probably 10% to 15% that are truly primary refractory. If you lump that in with the people that relapse within the first 3, 6, or 9 months, you start to build a picture of early relapse plus refractory. Then you have your positive PET scan at the end of treatment that you’re calling a partial response, but you don’t feel great about it and you don’t know necessarily which way that’s going to go.

I would like to also dig in and see if that percentage sounds like about what people experience in their practice. If they’re treating 5 or 6 patients in a year, is it 1 patient who might be truly refractory or is it 2 or 3 depending on the biologic features maybe?

KOSIEROWSKI: I would agree with those numbers. [It’s] very rare to see someone primarily refractory. The biggest problem is the early relapse.

NOWAKOWSKI: That has been our experience as well. The truly progressing patients are exceedingly rare. Patients who do not achieve complete metabolic response might be a bit more common. But again, it’s not a very frequent phenomenon and early relapse seems to be the biggest problem for a lot of these patients.

NOWAKOWSKI: Rituximab is used for other lines of therapy, so do you usually add rituximab or not? If yes, what regimen would be a preferred one in this setting for your practice?

SHAO: I used to use rituximab, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin. It’s an easy regimen. Usually I get some responses in the second line.

NOWAKOWSKI: It’s definitely very commonly used and has a long tradition, [with] multiple studies supporting its use. [It’s] modestly active but nevertheless it’s well tolerated. It can be adjusted to the patient performance status and other factors.

ARORA: Some of the relapses that I’ve seen are also in the elderly population. Those people that you really can’t give R-CHOP to and you’re going with the R-mini-CHOP [reduced-dose regimen of R-CHOP], those are the people that I really feel uncomfortable about because [I wonder if they] are going to relapse. I’ve seen a higher degree of relapse in that population. The age for transplant is going up and up; it used to be 65 years and then 70. Now it’s pretty much functional status. So there isn’t an age but it’s mostly performance status. If they’re truly ineligible, we have used R-squared [lenalidomide (Revlimid), rituximab] and GemOx [gemcitabine, oxaliplatin]. Modest activity, [but it] buys them some time. Those are my go tos.

It also depends on how quickly they relapsed. Did they relapse [after] more than a year or did they relapse within 6 months? Then using rituximab again may not be beneficial.

NOWAKOWSKI: I’m just curious; if they’re relapsing relatively early, they’re presumptively more resistant to chemotherapy. Would you be more inclined to use nonchemotherapy treatment like R-squared or ibrutinib [Imbruvica] or any of those?

ARORA: Yes I would be. Again, it depends on how they are doing and how quickly they need cytoreduction.

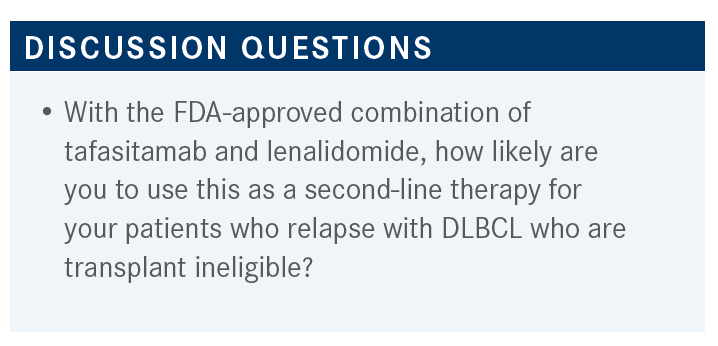

NOWAKOWSKI: When you’re thinking about your choices, what influences your selection of therapy? Is it the chance for long-term response, safety, tolerability, comorbidities, patient preference, or any other factors which you take into account to decide between various available options for those patients? We already mentioned some.

DY: I think for me the biggest thing would be if the patient is transplant eligible or not, which then would encompass all of these questions of can the patient tolerate it, can they tolerate more chemotherapy, how aggressive the chemotherapy would be. What are the comorbidities? What are the adverse events from the previous chemotherapy?

If we think that a patient can still be eligible for transplant, then I would be aggressive with my chemotherapy and I would still try those other regimens like RICE [rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide] and R-DHAP [rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin]. Then depending on the good response or not, proceed with transplant. If I think the patient is ineligible, then that’s when I would probably use either R-GemOx or [one of the many] other CD19 and CD30 targets, plus CAR in the later line.

ARORA: I would also throw in the availability of clinical trial if there is something available. That would be preferable in this situation, if [the patient is] eligible.

NOWAKOWSKI: How do you usually identify a trial? Do you have it at your institution or do you try to refer for the trials or a mix of both?

ARORA: Both. There are some trials that we have and then Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center is around the corner for us. Referral and distance is not an issue.

SMITH: I think Dr Dy’s point is critical. That first decision on if a patient is transplant eligible means you’re going down the road of proving chemotherapy sensitivity and trying to get as high of a complete remission [CR] rate as you can but using a regimen that has a standard intensive platinum backbone and then perhaps adding a drug in some of the trials. We’ll add a novel agent to those intensive platinum regimens, and you have to see how that goes in that subgroup of patients. It’s the patients who either progress or right at the outset you know aren’t going down that path that it opens wide up to all of the other drugs. But I completely agree that that’s how we also look at that first decision tree.

GOLDBERG: What about the decision in the beginning once you get the patient in CR and you don’t know yet what’s going to happen about storing their marrow [after first-line therapy]?

SMITH: Our preference at our institution is to try not to wait it out to 3, 4, or 5 cycles of any platinum therapy. We try to get [bone marrow tests] after 2, maybe 3, cycles. But also, with plerixafor and modern methods, we’re able to [get] stem cells out of the marrow at a fairly high rate, so chemotherapy mobilization and plerixafor have reduced the urgency in making that decision too early, I think.

NOWAKOWSKI: That’s a great point. Our practice is similar. We used to collect some of those patients’ [cells] who are particularly high risk. We did a small retrospective study here that [showed] we rarely use those cells and we can usually collect them now with plerixafor. That seems to be not commonly used nowadays.

GOLDBERG: Did you not use them because people didn’t relapse?

NOWAKOWSKI: Some folks did relapse, but then they have chemorefractory disease, some other reason, or something happened. They couldn’t get to stem cell transplant anyway. Then some people just did not relapse, so it was a mix. But overall we found that we’re using only about 15% to 20% of stored stem cells later on. Most of them were just not used and remained in storage for quite some time and then we abandoned this practice for that reason.

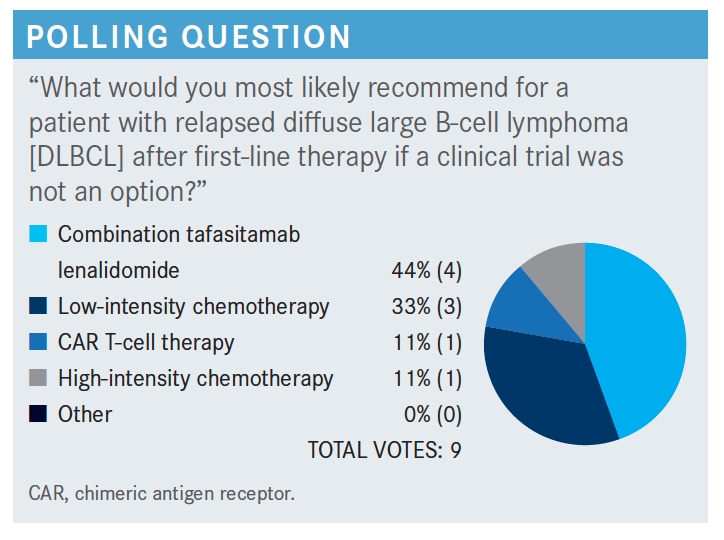

NOWAKOWSKI: It looks like there was a spread [across] the answers. About 11% of folks thought about CAR T-cell therapy, a third thought about low-intensity chemotherapy, high-intensity chemotherapy was 11%, and the combination of tafasitamab [Monjuvi] and lenalidomide [Revlimid] was 44%. Nobody voted for other options because most of them would either fall under low-intensity or high-intensity chemotherapy, presumptively, outside of the clinical trial.

SHENOI: Would polatuzumab [Polivy] plus bendamustine and rituximab [Rituxan; pola-BR] be a good comparable regimen for this group in the relapsed setting?

SMITH: It would be. The study [NCT02257567] included patients with 1 prior regimen, but pola-BR wasn’t able to achieve a fairly high CR rate.1 However, the progression-free survival [PFS] of that regimen was inferior and when you look at their expanded sets of patients they included in later analysis, it was always well under a year of PFS. You also get infectious toxicity with pola-BR in my experience and in subsequent real-world publication that’s been significant. But you’re right, we need to keep our perspective here. There are other options. There will be some patients more suitable for a slightly more intensive regimen where CR rates can be achieved with pola-BR as well, it’s just that the durability and the chemotherapy toxicity have to be considered.

NOWAKOWSKI: The comparisons of the studies are always difficult because you’re capturing different patient populations. That’s why we need to randomize studies to answer some of those questions or we can try to closely match those patients as much as we can nowadays in the real-world data studies.

But Dr Smith’s point is a good one because you don’t necessarily see the same tail in a pola-BR combination, which we see with [tafasitamab/lenalidomide] in terms of PFS and duration of response.2 We’ll see what additional follow-up will show up on the studies, but so far, those results are quite unprecedented in terms of the duration of response and the PFS curves outside of the CAR T-cell therapy and more aggressive solo approaches.

SMITH: For me, the logistics in the real world are always a little challenging. Certainly, trials have their own challenges in getting patients synchronized, for example. But with tafasitamab and lenalidomide, you’d like to start them on time. You want to give growth factor support. You need to consider the dose reductions carefully. It’s not an extremely simple regimen to give, although I get the point that we’ve given lenalidomide fairly frequently across hematologic malignancies, so familiarity is high. But I think the logistics of the regimen are a little complex, just as one example. Any other limitations [regarding why you] might not…use this routinely?

KOSIEROWSKI: Cost is always a factor.

SMITH: Cost for prescription drug coverage in lenalidomide remains a factor. Insurance remains highly unpredictable and a quick time [suck] for your week for many patients with prior authorization and appeals.

SHENOI: One thing I wanted to share is we always assume all our patients can afford it. But many of our elderly patients don’t have Medicare Part B and I’ve had patients who said they would like to come to the clinic and get my drug. They like to get it in the clinic, just taking the tablet. We always assume that they want to take it at home but sometimes they want to take it in the clinic.

NOWAKOWSKI: It is a great point and a definitely important factor. Europeans now have generic lenalidomide. I wonder when we’re going to have it within the United States, but it’s probably still a couple of years away.

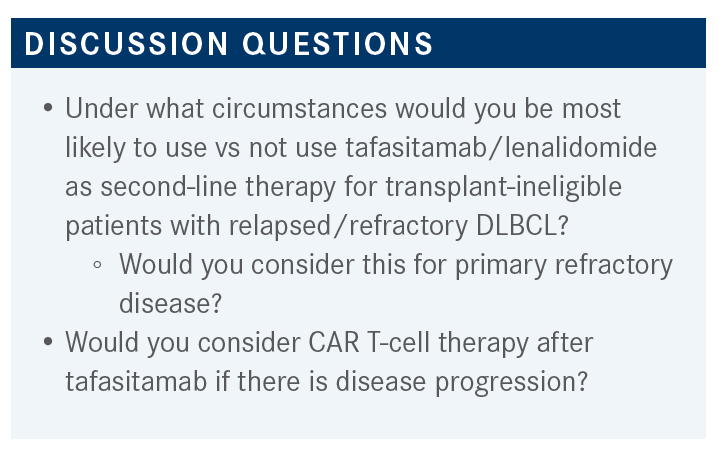

NOWAKOWSKI: There was an activity in [the relapsed/ refractory DLBCL] patient population.2 Would you consider tafasitamab/lenalidomide for primary refractory patients or due to initial study design would you say that’s probably not a good idea? You may argue that repeating chemotherapy in those patients is also not a good idea because if they progress after chemotherapy [why] would you give them more chemotherapy, rather than switching to a different modality?

DY: I would consider giving it in [a patient who is] primary refractory, especially since the data [showed] that giving it sooner shows even better and longer response.

SHENOI: My one question [is], is this regimen as good in germinal center B cell [GCB] as in activated B cell [ABC]? Because the 1-step relapses are mainly activated. [For example,] polatuzumab is much better in the ABC than in the GCB.

NOWAKOWSKI: I’m not aware of data which show that polatuzumab is different in ABC vs GCB subtype. I think groups have shown that, in general, in the relapsed/ refractory setting, relapse tends to be the equalizer for those molecular subtypes. Double-hit [lymphoma] is bad after relapse, but with GCB or ABC, the outcome is [the same for] those patients, surprisingly. The front line is different. The GCB population do better. They’re more likely to be cured than ABC. But when you relapse, they both have very similar event-free survival and overall survival.

Now, with the tafasitamab/lenalidomide combination, there was a lot of interest [in whether] it is going to be particularly active in non-GCB subtype because lenalidomide is active in non-GCB. The response rate is slightly higher, but that’s based on a relatively small amount of patients and still a significant proportion of patients with GCB subtype respond to it. [Presumably this is] because maybe it’s less of a direct cytotoxic effect but has to do more with modulating microenvironment, along with the antibodies as a mechanism of action.

SMITH: There was a slightly superior hazard ratio for non-GCB in this study of tafasitamab/lenalidomide [L-MIND (NCT02399085)], but I don’t believe it was a striking or significant improvement for the non-GCB subgroup. But it does go to confirm some prior suspicion that non-GCB may be more sensitive to lenalidomide somewhat.

NOWAKOWSKI: Would you consider CAR T-cell therapy after tafasitamab if there is a disease progression? I personally would, particularly if the CD19 expression was there, but I’m curious [about] your opinion.

SHENOI: This group of patients is non–transplant eligible, so it’s unlikely that they’d be eligible for CAR T after that.

SMITH: That’s a really interesting point. I agree that there is some overlap in eligibility there, but I think increasingly, many investigators are considering CAR T-cell therapy, given the somewhat less-intensive lymphodepletion chemotherapy and the attenuated neurotoxicity in cytokine release syndrome that we’re seeing with new CAR T-cell therapies, [which are] significantly less toxic than autologous transplant.

Now, that may be in the eye of the beholder and we need good comparative studies, but I think there are CAR T candidates who are not transplant candidates out there. But I completely agree with the point in general; in principle, there is a lot of overlap between those groups. This question I think is more getting at the CD19 aspect and whether we’d consider sequencing CAR T after exposure to that drug. The answer for me is yes.

REFERENCES

1. Sehn LH, Herrera AF, Flowers CR, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(2):155-165. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00172

2. Salles G, Duell J, González Barca E, et al. Tafasitamab plus lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (L-MIND): a multicentre, prospective, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):978-988. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30225-4

Gasparetto Explains Rationale for Quadruplet Front Line in Transplant-Ineligible Myeloma

February 22nd 2025In a Community Case Forum in partnership with the North Carolina Oncology Association, Cristina Gasparetto, MD, discussed the CEPHEUS, IMROZ, and BENEFIT trials of treatment for transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.

Read More