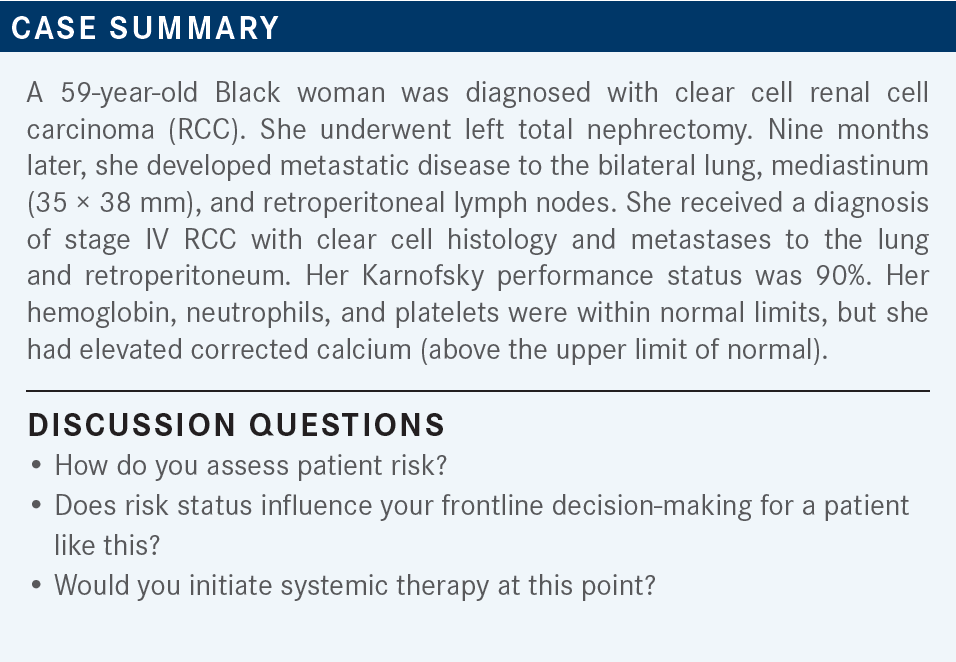

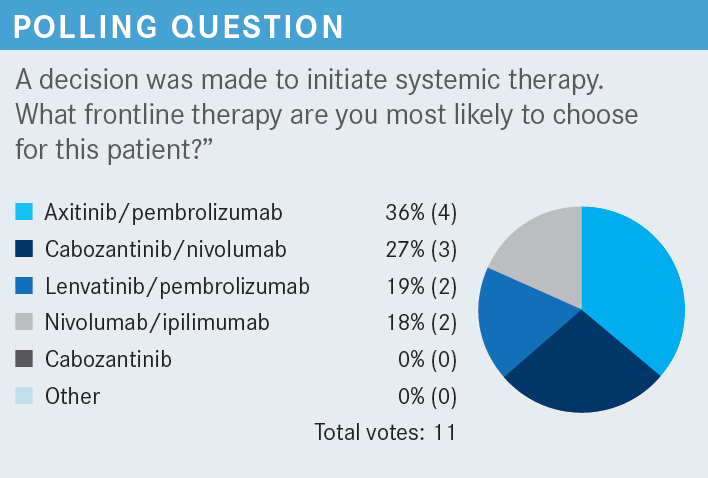

Roundtable Discussion: Participants Consider Risk Assessment and Frontline TKI Management for Clear Cell RCC

During a Targeted Oncology case-based roundtable event, Moshe Ornstein, MD, MA, discussed how to treat a patient with intermediate-risk renal cell carcinoma.

Moshe Ornstein, MD, MA (Moderator)

Genitourinary Medical Oncologist

Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Center

Cleveland, OH

ORNSTEIN: Are you using these risk calculators in your clinics to assess a patient’s risk status? And are you using them to decide which treatment to choose for a patient? If so, how?

CHOWDHARY: I do use a risk calculator. It is helpful because if they [have] favorable-risk disease, I feel you can [discuss] whether they should even start treatment.

This [case] is more intermediate risk because there is at least 1 risk feature I saw. I do normally use it. I still feel it’s not unhelpful to have that as you’re grading them.

ORNSTEIN: Let’s say this patient was poor risk. Do you choose your treatment differently, depending on the risk group?

CHOWDHARY: No, not really. If someone has low burden of disease or is older, I may choose an immunotherapy [IO] route alone. But [generally], if they’re favorable risk, I will have that discussion with them about whether we can even hold off on treatment.

If they’re intermediate or high risk, generally my treatment paradigm has remained the same. It’s more a question of whether I want to do IO alone vs a tyrosine kinase inhibitor [TKI]/IO combination. That’s where my inflection point is as I’m deciding.

ORNSTEIN: It sounds like [it’s a no-brainer with] intermediate or poor risk: they’re going to get treated. If somebody is favorable risk, you might choose a monotherapy. You feel like there’s a little more flexibility with that patient, especially if the disease burden is low.

Does anyone else care to weigh in? Do you use the IMDC [International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium] risk criteria in clinical practice, or is it just something you have in your pathway that you have to select? Or do you overlook it and say, “I’m going to treat the patient with systemic therapy if they have metastatic RCC”?1

ANWAR: I do look at the IMDC scores. Because if you look at the [National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines], the preferred regimen is a little different, [especially for IO alone].2 It is preferred in the [intermediate- and] poor-risk group, but it is not a preferred regimen for the favorable-risk group. Also, [I consider] whether to start the treatment now or later in those with favorable risk, depending on their tumor burden.

ORNSTEIN: What you’re saying is that ipilimumab [Yervoy] and nivolumab [Opdivo] are not [preferred] in favorable risk, so…that would be good to know. Also, if they’re favorable risk with maybe a lower disease burden, then that would at least give you an option to consider surveillance for the patient.

I do something similar. I tend to think the IMDC risk calculators don’t tell us as much about a specific patient’s biology as it does a general risk. I don’t use it a whole lot to select treatment options. I tend to treat across the risk groups very similarly.

My first question is always: Can I continue to watch a patient? But once I decide to pursue treatment, our paradigms tend to be fairly similar. This patient seems to have a higher tumor burden, because there are multiple sites of disease and they recurred within a year of treatment. Hemoglobin is low, so this is an intermediate-risk patient with a reasonably high burden of disease.

JABBOUR: [In your experience], what are the adverse events [AEs] or toxicities that make you decrease the dose [of lenvatinib]? I have given lenvatinib in other diseases, but I’m hesitant because I have good experiences with cabozantinib [Cabometyx] plus nivolumab and axitinib [Inlyta] plus pembrolizumab. I have not given [lenvatinib] yet for RCC, but what toxicities most commonly make you decrease the dose or hold it with lenvatinib?

ORNSTEIN: You’re not the only one to say, “I’ve had some bad experiences with lenvatinib in endometrial or thyroid cancer. I have other options that are available in kidney cancer. I see the numbers look great, but I still have cabozantinib, which I’ve had good experiences with.”

JABBOUR: Exactly.

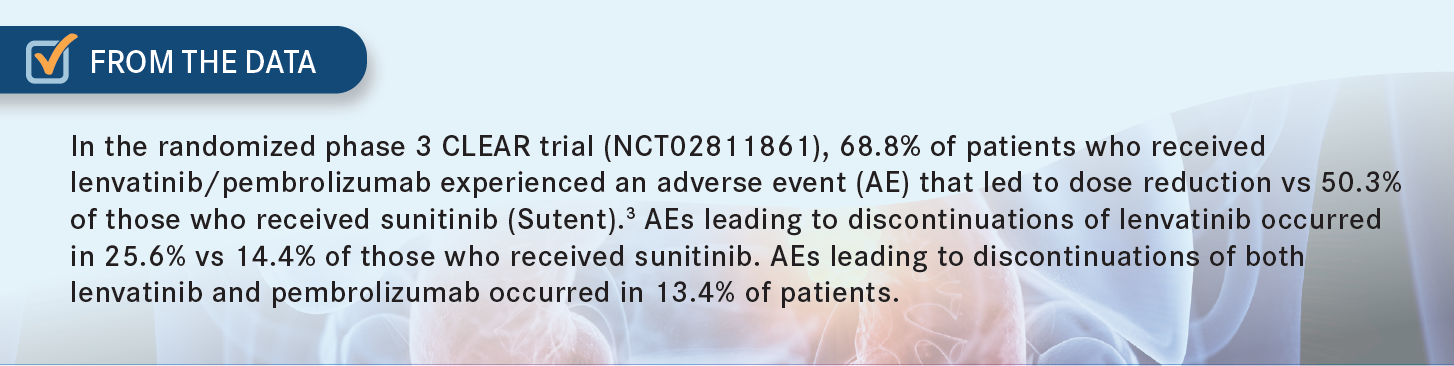

ORNSTEIN: I have found that the dose reductions are most prominent for diarrhea and, probably more than diarrhea, fatigue. The patients just look different after 6 weeks. I haven’t had to dose reduce everybody. I’ve probably dose reduced a little less than the trial did. I’d say probably a little more than 50% are requiring a dose reduction. For the others, I’m just trying to be a little more clever with how to manage the toxicities.

It takes time to find the right dose. The doses go from 20 mg to 14 mg. Is there an in-between dose you can use? How do you decide to go from 14 mg to 10 mg? In my experience, it’s been diarrhea and fatigue, but I do give the patients a heads-up that it takes time to find that balance.

For those who did not select lenvatinib and pembrolizumab, is it because of a fear of the toxicity? Is it [because you have] not seen the data? Is it [because you’re] saying, “I already have a combination I’m comfortable with. I don’t want to bother my group. I’ve got a very busy practice.” [Or] is [there another] reason that would lead you to choose something else over this combination?

JABBOUR: The toxicity. In endometrial cancer, my patients were miserable. Of course, the data [for lenvatinib/pembrolizumab] are great, and I want to use it now. I’ve been reviewing a lot of data about it, but my patients with endometrial cancer were [unhappy]. That is the only fear, because when you have something you’re comfortable with and you have good data with it—should I do it or should I wait? You’ll always be comfortable with something, and you don’t want to change right away, but I’m sure I will try it.

ORNSTEIN: That’s fair. You look at the data and they look a little better, but is it better enough to say you’re going to switch something you have experience with and your patients are tolerating? I think it’s open for discussion.

HUANG: I’ve seen the toxicity in other cancer types. But in addition to the toxicity, if somebody with RCC is not presenting with many symptoms, is not suffering from the disease, and doesn’t require a fast response, I would prefer not using a combination of TKI/IO.

One [factor] is if I order something for chemotherapy or immunotherapy, it can get approved within a week. I can start treatment within a week. If I order an oral TKI, it has to go through insurance and specialty pharmacies and takes a longer time, so that’s another concern. I think it’s mainly [because of] the toxicity. But with the other concerns, I just have not tried [lenvatinib/pembrolizumab].

ORNSTEIN: If you have a patient [who] needs a response now, they need the IO/TKIs with higher response rates compared with the IO/IO, but it’s easier to get the IO/IO and the intravenous agents approved than the orals through the specialty pharmacy.

Let’s say you had a patient who came in and was symptomatic with back pain or whatever else, and you were to choose an IO/TKI recognizing the challenges— what do you think?

HUANG: [In that case, I probably would]. I have not tried [lenvatinib] in RCC, but [I have] in other cancer types. [However], I had a miserable experience [almost every time] in thyroid cancer and HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma], and I’ve reduced the dose multiple times. My patients got anorexia, fatigue, and nausea.

ORNSTEIN: [If you do try it], you can report back to us how it goes. It is interesting. The dosing is, of course, different in different tumor types, as well. The patient makeup is different.

MAITI: So far, I haven’t had a chance to use this regimen from the CLEAR trial up front.3 The toxicities are definitely prohibitive. But in the absence of head-to-head comparison, although the data are pretty compelling, I’m still on the fence to justify the toxicities, especially if we have the option of using it subsequently. I’m still debating, but I haven’t had the opportunity to use it in the front line yet.

ORNSTEIN: I agree. I think there is a certain perception. There is also toxicity in the trial that comes along with this drug.3 Not so much with the pembrolizumab, but more so with lenvatinib, specifically if you’ve had rough experiences in the past.

I’ve used a fair amount of this recently. Again, I do think it’s been the fatigue and diarrhea that most of the holds and dose reductions have been about. I didn’t use a lot of cabozantinib/nivolumab; I used a lot of axitinib and pembrolizumab, partially because of the KEYNOTE-426 trial [NCT02853331] that was run by [Brian I. Rini, MD], when he was here [at the Cleveland Clinic].4 When it became approved, it was not a surprise that we were using a lot of it. It was the first IO/TKI combination to come out, and the axitinib has a short half-life and is fairly well tolerated. I find that the flavor of the toxicity seems to be similar across them, but I have that same hesitation up front: Do I want to try this in the context of having other combinations?

SAFA: Are there any data about—or have you [done] it— escalating the dose of lenvatinib, like we use regorafenib [Stivarga] in HCC or colon cancer? There were data [that showed] if you escalate the dose, it’s better tolerated. [Or] like neratinib [Nerlynx] in breast cancer. Do you think [escalating the dose] will work with lenvatinib?

ORNSTEIN: It’s a good question. In clinical practice, I try the 20 mg. In the trial, 30% of patients were able to tolerate it [From the Data3]. I don’t want to take my chances for that subset of patients. It’s easy enough to dose reduce, especially because there’s a dose exchange program, where for up to 15 unused doses of the 20 mg, you can send it back to the company, and the company will send the next dose reduction for up to 2 weeks of dosages. I start where the data are.

I think you’re pointing to this concept with TKIs called linear pharmacokinetics, where as a whole, a higher dose will mean a higher plasma level and will have greater efficacy. We have data for that in RCC, as well, titration up, even at the time of disease progression.5

One of the reasons I don’t do it, and one of the reasons I don’t encourage it, is I find that once a patient is on one of these medications and tolerating it, there’s a great deal of hesitation to ramp up the dose. I find it’s much easier for a physician to say, “You’re not tolerating this well. Let me dose reduce.” It’s much harder to say, “I’m giving you this combination. It might be a little rough, but if it’s not too rough, let’s crank it up a little.” That’s harder for physicians and patients. I do think that if someone were to start at a lower dose, they should try to get to the highest dose, because that’s where the efficacy is. There is going to be a subset of patients [who] will respond at a higher dose and not at the lower dose. I start high and drop, as opposed to the other way around.

I think the proof to that is the axitinib and pembrolizumab. In [KEYNOTE-426], patients could uptitrate from 5 mg to 7 mg to 10 mg.4 [The investigators] didn’t show any data of that in the results, and I believe that’s because it wasn’t done. Again, you have a patient [who] has a little diarrhea; they might be on the right dose for them, but you’re not going to push too much.

BASTOLA: I think part of it is also because we don’t have a lot of experience with these drugs. So, we may have a handful of patients and if they flame out, [that] gives us pause. Whereas for lung cancer, we treat so many of them that if they get pneumonitis or [another AE], we now have more experience [with how] to handle it. I think a lot of it has to do with experience.

These are not toxicities we can find in bloodwork. It takes a lot of patience to sit with them, talk to them, [and] ask them [about their AEs]. A lot of us may not even have a lot of support systems to spend so much time with them. I feel like a lot of it has to do with just not being able to spend so much time figuring it out. It’s not as simple as “the platelets are low, let’s hold, then repeat laboratory tests next week, then we can go back.” Sometimes patients are very hard to read. It’s difficult to tease out what’s happening with them [because] it’s mostly symptom based.

ORNSTEIN: I completely agree. I think some of this goes back to how this is not the most common of cancers. In [oncology practice] groups, especially busy groups that may not have a lot of experience with this or a lot of support in terms of being able to sit down and tease out whether the diarrhea is from the IO or the TKI, that could be a little tricky. I think that’s why what you see in these answers is [physicians] saying, “I’m going to go with the combination I’m comfortable with, because there is a survival benefit compared with sunitinib.”

The first lenvatinib dose reduction is the 14 mg, then 10 mg, then 8 mg.6 There are [a lot] of tricks when it comes to TKI toxicity. You can withhold doses, then continue. This is not in the label but, at least in my experience, this works in some patients. You withhold the dose for a few days, ramp up the supportive care for the patient, then continue with that dose. If you feel like it’s going to be too much, you can dose reduce. Discontinue if a patient can’t handle it.

It’s the same thing with pembrolizumab.7 This requires less of a discussion because it’s used in pretty much every cancer. [However], I do want to call your attention to that dose exchange program. I think there are more companies that have [a dose exchange program] than we recognize, especially for [physicians] who are not familiar with these 10-mg and 4-mg capsules. Having your pharmacy or your supportive care team be aware of that is [good].

REFERENCES

1. International mRCC Database Consortium. IMDC. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://bit.ly/3CgfS9E

2. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Kidney cancer, version 3.2023. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://bit.ly/2TAx1m3

3. Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha SY, et al; CLEAR Trial Investigators. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(14):1289-1300. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035716

4. Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(12):1116-1127. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1816714

5. Ornstein MC, Wood L, Elson P, et al. Clinical effect of dose escalation after disease progression in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15(2):e275-e280. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2016.08.014

6. Lenvima. Prescribing information. Eisai Inc; 2021. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://bit.ly/3LQocS1

7. Keytruda. Prescribing information. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp; 2021. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://bit.ly/3LZGvV2

Enhancing Precision in Immunotherapy: CD8 PET-Avidity in RCC

March 1st 2024In this episode of Emerging Experts, Peter Zang, MD, highlights research on baseline CD8 lymph node avidity with 89-Zr-crefmirlimab for the treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and response to immunotherapy.

Listen

Beyond the First-Line: Economides on Advancing Therapies in RCC

February 1st 2024In our 4th episode of Emerging Experts, Minas P. Economides, MD, unveils the challenges and opportunities for renal cell carcinoma treatment, focusing on the lack of therapies available in the second-line setting.

Listen