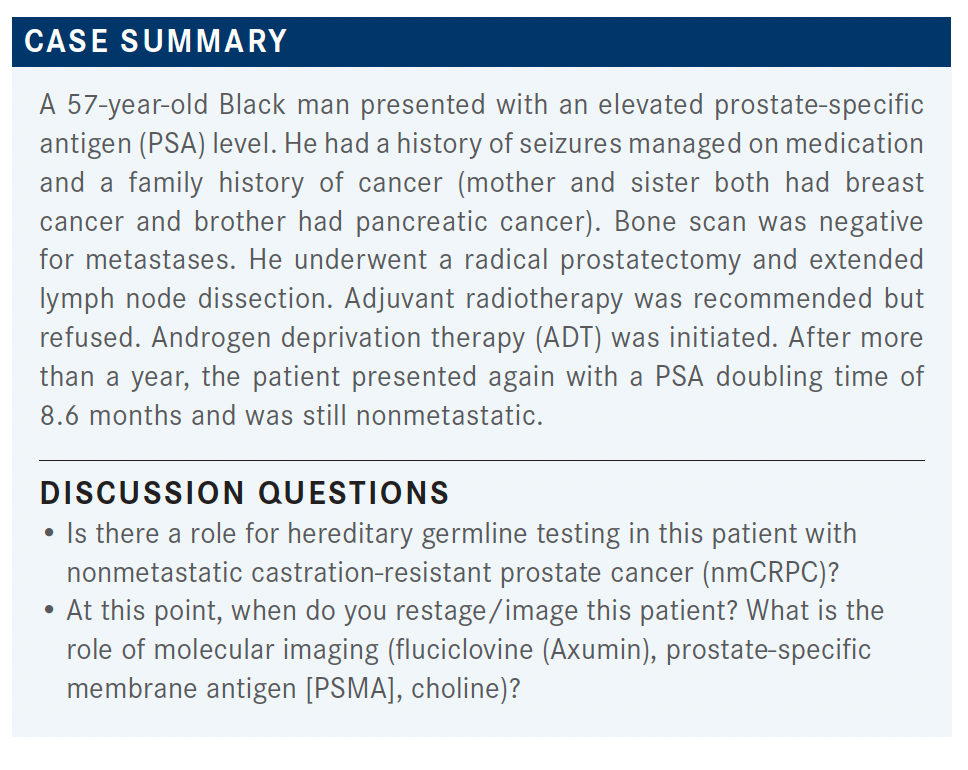

Roundtable Discussion: Dorff and Participants Compare PSA Doubling Times and Treatment Decisions in nmCRPC

One year following treatment with androgen deprivation therapy, a 57-year-old patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer presented again with a PSA doubling time of 8.6 months and was still nonmetastatic.

Tanya Dorff, MD

Tanya Dorff, MD, the head of the Genitourinary Cancers Program, and associate Clinical Professor in the Department of Medical Oncology & Therapeutics Research at City of Hope, moderated a Targeted OncologyTM Case-Based Roundtable event around a prostate cancer patient case.

DORFF: Is this patient someone you would consider for germline testing?

LIU: [I would], given his strong family history.

DORFF: Yes, he did have a strong family history. Do you refer to a genetic counselor or do you order it yourself and then only refer if it’s positive?

LIU: I usually refer them to telegenetics.

CHARU: I usually order it myself, but if the insurance gives me a hard time, I send the patient to a genetic counselor.

FU: We can order our own test. Let’s say the patient has no family history— would you still order the test or refer to a genetic counselor?

DORFF: The NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines suggest germline testing for anyone with high-risk [or recurrent] prostate cancer.1

FU: To be honest, I’ve been ordering a lot of tests and have not seen a single positive one.

DORFF: That can be frustrating. But I suppose it provides some reassurance. I always tell [patients] why I want it; [it will potentially affect their] siblings or children and their screening, but when it’s negative then maybe that’s a relief. [The incidence of getting a positive test] should be 10% or 15%, according to Pritchard et al in the New England Journal of Medicine, but it feels like a lower rate.2

YEH: Let’s say a patient does not have a strong family history. You’re just checking [for germline mutations] because the patient has prostate cancer. Will you also check for BRCA and homologous recombination repair [deficiency]?

DORFF: Yes, I think that makes a lot of sense, especially in the absence of a family history where you want to know in the future whether you could have a treatment option for them.

How about imaging? Are you using fluciclovine PET scans? Are you referring out for PSMA PET scans or choline PET scans?

DEKKER: I’m using fluciclovine and just started to refer for PSMA.

DORFF: Do you order the CT/bone scan first and then go to a PET scan, or do you just go right to the PET scan? Do you feel like it adequately shows you bone?

DEKKER: I will go straight to PET scan.

CHARU: I also order a PET scan.

DORFF: There is a lot of discussion before they’re castration resistant about whether we should change our salvage radiation plan based on the PSMA PET. It’s surprisingly still pretty controversial. To me, if we see something we should react to it because PSMA PET is validated as being accurate. But there’s still controversy, and there are some prospective trials trying to validate [PSMA PET further]. They’ve shown that [physicians] do change management, but now they’re trying to go back and prove whether that’s the right thing to do—whether it impacts patient outcomes.

DEKKER: If you find metastatic disease or highly suspected metastatic disease in a borderline patient, you may forgo surgery or move directly to radiation or even basically treat as metastatic up front.

DORFF: Yes, I think [PET scan makes sense for staging high-risk, localized disease]. PET scans are much more useful when the PSA is low, like 0.2, 0.4, or 0.5 ng/mL. [In that case] it makes no sense to get a CT scan. How often do you image your patients [with rising PSA]?

DEKKER: It depends on what I am planning to do. If I am watching a patient with no therapy, probably every 3 or 4 months.

LIU: I do the same—about 3 months or when the PSA doubles.

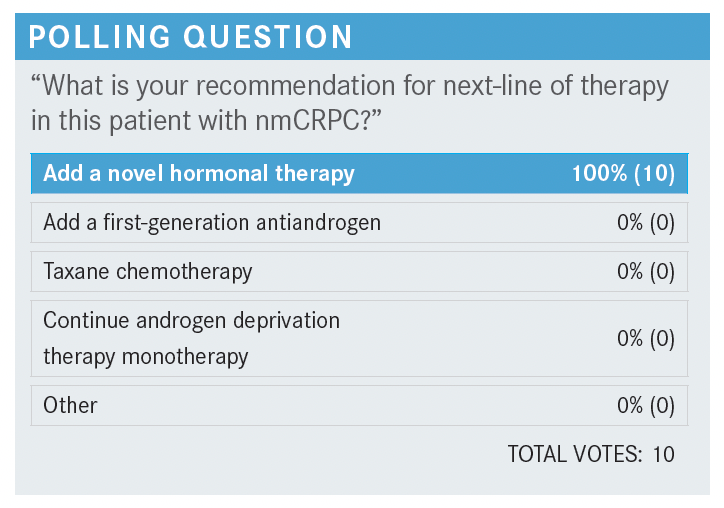

SARKISSIAN: You can probably just knock out taxane chemotherapy because I think there are more than enough survival data and time-to-chemotherapy data to really put that in our back pockets for [issues] like visceral crisis.

DORFF: Most people favor adding a novel hormonal therapy: enzalutamide [Xtandi], apalutamide [Erleada], [or] darolutamide [Nubeqa]. This feels like a big moment for the patient because often they’ve been on intermittent hormone therapy and now you’re telling them it’s going to be lifelong and you’re going to add a second drug.

How much does quality of life come into play with your discussions with these patients at this juncture? Are patients more worried about their cancer and their survival, or do they really worry about the adverse events [AEs]?

LIU: I think it’s both for my patients. They’re monitoring their PSAs very closely and worried about developing metastases, but they also care about their quality of life on hormone therapy, whether it’s hot flashes, fatigue, fractures, or muscle loss.

ALEXSON: I think quality-of-life issues always matter, especially the fatigue and muscle loss, [considering that] this patient is only in his 50s.

LIU: For my patients, financial [concerns are also important].

DORFF: That’s a great point. Cost might influence our selection or a go/no-go decision.

YEH: For my patients, it’s the leuprorelin that they are most concerned about. A lot of them dread having that medication: the hot flashes, the fatigue, the muscle problems, and [diminished] libido….They’re more OK with the second-generation enzalutamide [because] the AEs are not too bad. I dose them based on testosterone level. If their testosterone levels start to rise, then I’ll give them a dose. But if [the level stays] low, less than 50, then I might just watch it.

CHAND: I do the same thing with the testosterone level. It’s interesting; even months after stopping the leuprorelin, some of these men don’t regain testosterone levels above 50 ng/dL.

SARKISSIAN: Recently I had a patient with anxiety.…He could not commit to leuprorelin, but I was able to give him apalutamide. The apalutamide dropped his PSA by almost 3 orders of magnitude just by itself, without ADT and the menopausal AEs. Most studies have ADT running in the background. I don’t know how many studies there are with novel agents without ADT. It might be an interesting angle to take.

DORFF: Enzalutamide monotherapy…can be effective. [This patient is] different because his cancer is castration resistant. But I do think there need to be more studies of noncastration approaches, and maybe monotherapy with these newer agents could be quite effective. But it’ll take a while for a really definitive study to happen. But I will say I have done it on some patients who have refused leuprorelin. It does work. Probably not as well.

When patients are on leuprorelin and they’re struggling with all these AEs and they say, “You’re going to add a pill that’s going to be even more intensive,” I usually counsel them that I don’t see a significant increase in AEs, generally speaking, with [enzalutamide, apalutamide, or darolutamide]. There can be more fatigue. Do you see a lot of added AEs when you add one of these agents on top of the leuprorelin?

CHAND: Rarely. I recently had a patient on enzalutamide who refused to take the medication because he was having a lot of nausea, vomiting, and fatigue; he could barely get out of bed. I’ve had so many patients on enzalutamide and they’ve never complained of anything. But we switched him to apalutamide and he seems to be tolerating it better. I think there is some difference between the agents.

CHARU: I see the same thing with enzalutamide. They have more fatigue.

LIU: I think my older patients have a little bit more fatigue with enzalutamide. But otherwise, it’s well tolerated.

SHIN: Do you ever try antiandrogen withdrawal?

DORFF: Sure. There was a study where they switched out the prednisone for dexamethasone and saw a lot of patients’ PSAs decline. I’ve experienced it in my own patients. It’s interesting that the switch can make such a difference.

YEH: How do you switch from prednisone to dexamethasone? What’s the dose?

DORFF: The dose is 0.5 [mg daily]. Some of my colleagues have said they’ve tried it and it didn’t work, but I’ve done it in a handful of patients and I’ve had a few where it really worked.

LIU: Same here. Yes, it did drop.

DORFF: These are old-school maneuvers [from] before we had lots of lines of therapy. We would do antiandrogen withdrawal; we would switch out the steroid. A lot of these patients’ cancers progress slowly, and you have that luxury. Obviously, some cancers progress rapidly and you need to just move on.

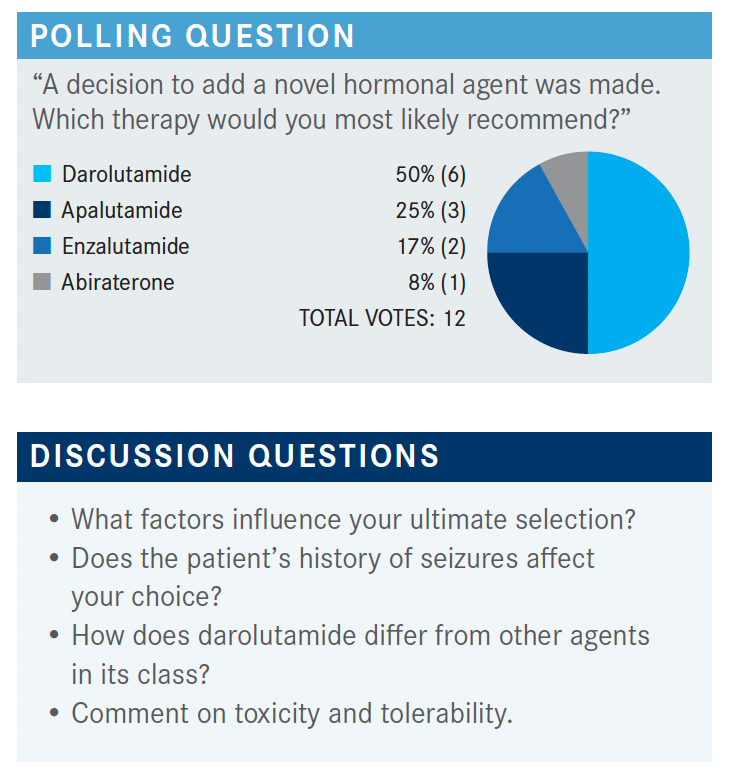

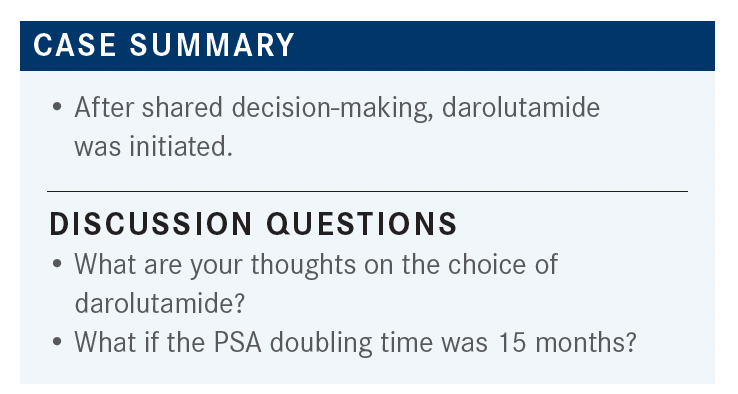

DORFF: We have a pretty broad split. We have maybe a few more darolutamide fans. Anyone want to lobby for their choice—why they chose that drug? This patient has a seizure history. That’s an important factor to think about. Seizure history is relevant because, unlike enzalutamide and apalutamide, [darolutamide] doesn’t cross the blood-brain barrier, so it seems a reasonable choice.

CHARU: I think darolutamide is a slightly better-tolerated drug overall.

CHAND: I was told by the drug company that [darolutamide] doesn’t cross the blood-brain barrier, so the fatigue tends to be less compared with enzalutamide. So, patients tend to tolerate it a little better.

DORFF: Does that play out in your experience?

DEKKER: That may be hard to tell. We all have more patients who have fatigue on enzalutamide because we have used it for much longer than the darolutamide, which has not been around for as long.

DORFF: Does anyone have any apalutamide experiences?

CHAND: I have 1 patient on it, and he seems to be doing well. He’s been on it for 2 years now and I haven’t had any complaints.

DORFF: I think overall they’re well tolerated. I feel like more of my enzalutamide patients have AEs such that I have to either lower the dose or [discontinue the drug]. But I’ve seen AEs with all of the agents.

DORFF: Are you calculating doubling time? Do you only give [enzalutamide, apalutamide, or darolutamide] in nmCRPC for fast doubling times?

LIU: I generally do, yes.

SARKISSIAN: Yes.

DORFF: What if someone’s doubling time is 10 or 11 months and they say, “I’m really nervous; treat my cancer”?

FU: That’d be fine. I use 10 months as a cutoff. I give them the option.

DORFF: What about the trials in which the PSA had to be 2 ng/mL? I’ve had patients begging for a treatment when their PSA is 0.2 ng/mL, because they’re watching it rise even at those lower levels. Do you wait for a certain number or do you base it on doubling time?

FU: For 0.2 ng/mL, I would say no.

CHARU: I think if it were 0 or 0.1 ng/mL to begin with and it goes to 0.6 or 0.8 ng/mL within 6 months, then I’m more inclined to consider doing something.

FU: For such a low value, I don’t think there is harm in waiting a little bit.

CHAND: That’s what I was going to say. Why not wait a little bit longer? Let the PSA rise. Because these medicines are not free of AEs. You have to consider risk and benefit of these drugs vs close observation.

CHARU: But some of the data show that if their PSA doubling time is 6 months, even if it’s not very high, there may be benefit to starting early. That was my understanding.

DORFF: I think it’s a challenge. Men who are really watching their PSAs and know that doubling time is important can push even before they get to integer numbers. “Why are you just watching my PSA double and doing nothing?” I find some of these discussions very challenging. But I hear your argument that these are not completely benign medicines. There are AEs and there’s cost. I tell them all those things.

DORFF: Have the survival data [for apalutamide, enzalutamide, and darolutamide] changed your enthusiasm? When they were first approved, did MFS feel like a strong enough reason, or is it really the survival that would impact your use of these drugs?

SARKISSIAN: I think for me it was always MFS.

CHARU: I agree with that. I also feel that MFS is important.

CHAND: Yes, but knowing that it also translates into better OS if you start early is even better because then you feel more strongly about starting earlier.

LIU: I agree. The data are compelling enough for the MFS and now, with the OS data, it confirms our conclusions that these are good data to start patients early on.

DEKKER: [The data show] really long MFS, so you assume that it probably would translate into OS. [If the MFS] had been 4 or 6 months less, it could very well have gone either way.

DORFF: A lot of you said you do go straight to PET scans. I’m not sure whether that’s only in the first biochemical recurrence or even in patients with castration-resistant biochemical recurrence. If so, if they do have a PET-detected metastasis, how do you categorize them? Are you treating them as metastatic or do you treat them as nonmetastatic?

DEKKER: I treat as metastatic.

LIU: Oligometastatic?

DORFF: So are you doing some focal radiation if you find oligometastasis on the PET?

DEKKER: Yes.

DORFF: I have had a couple of patients where the PET scan finds inguinal nodes. A lot of us say you don’t get inguinal nodes with prostate cancer. Would you believe that? Would you biopsy it? Would you radiate it if it were the only site of disease?

DEKKER: I would biopsy it.

CHARU: I would…do a core needle biopsy.

FU: Remember, this is PET scan positive, not CT positive.

CHARU: There is a false positive rate in PET scan, as you know.

FU: There is no PET scan–guided biopsy.

DORFF: I think it’s challenging. I’ve had some PET scans that show something that we cannot biopsy and yet we have some doubts about it. It sounds like a lot of you really trust the PET scan and so then you look at metastatic therapies rather than the nonmetastatic group.

DEKKER: Yes. I believe that the majority of patients diagnosed with nonmetastatic disease actually have metastatic disease.

YEH: Let’s say you do find a focal spot and you radiate the focal spot; what if the patient is totally asymptomatic? What’s the role of that?

DEKKER: We make the same assumption that we do with melanoma, with renal cell, isolated lung, isolated colorectal. Isolated disease could be isolated disease.

CHARU: I think for oligometastasis, you can’t radiate them. [If] the patient has an inguinal lymph node, I wouldn’t just consider that as a metastatic disease unless I biopsy it, even though it’s PET positive, because the PET could be a false positive.

DORFF: [Regarding] oligometastatic radiation, we have the SABR-COMET trial [NCT01446744], which wasn’t prostate specific but showed adding stereotactic body radiotherapy to oligometastases on top of standard therapy improved survival.3 You could talk to your radiation oncologist about that. Then the prostate-specific trials are STOMP [NCT01558427], POPSTAR [U1111-1140-7563], [and] ORIOLE [NCT02680587]. I think there’s a growing body of evidence. I agree we don’t know for sure it’s the right way to do things, but I guess one of the reasons individuals are using PET scans is the hope to find it before it’s widely metastatic. But we have a lot to learn there.

I thought the quality-of-life data for these trials were interesting: There was a delay in deterioration in quality of life. So, delaying metastasis has that added benefit.

REFERENCES:

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Prostate cancer, version 2.2021. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://bit.ly/34xiIXZ

2. Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):443-453. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603144

3. Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard of care palliative treatment in patients with oligometastatic cancers (SABR-COMET): a randomised, phase 2, open-label trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10185):2051- 2058. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32487-5

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More