Ornstein Advises on Starting Dose and Management of Lenvatinib in RCC

During a Case-Based Roundtable® event, Moshe Ornstein, MD, MA, provided guidance on dosing and toxicity concerns in a patient treated with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for advanced renal cell carcinoma.

Moshe Ornstein, MD, MA

Genitourinary Medical Oncologist

Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Center

Cleveland, OH

CASE SUMMARY

Medical and surgical history

- A 59-year-old woman presented with a left renal mass.

- She underwent left radical nephrectomy, which revealed clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

9 months later

- The patient developed nodules in both lungs, with mediastinal (35 × 38 mm) and retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

Diagnostic workup

- Lung biopsy confirmed stage IV RCC, clear-cell histology

- Karnofsky Performance Status score: 90%

- Hemoglobin level: 11.1 g/dL

- Corrected calcium, neutrophil, and platelet levels within normal limits

Treatment

- The patient was scheduled to begin 200-mg pembrolizumab (Keytruda) every 3 weeks plus 20-mg lenvatinib (Lenvima) daily.

PEERS & PERSPECTIVES IN ONCOLOGY: What are your thoughts on the dosing approach for patients such as this?

ORNSTEIN: This patient is scheduled to begin 200-mg pembrolizumab every 3 weeks plus lenvatinib 20 mg daily. The dosing is different for all the [frontline] regimens. Lenvatinib is 20 mg; that’s a pretty high dose.1 When it’s given together with nivolumab [Opdivo], cabozantinib [Cabometyx] is given at 40 mg [but] when cabozantinib is given on its own in the refractory setting, it’s given at 60 mg.2 Axitinib [Inlyta] is given with pembrolizumab…at the usual dose of 5 mg twice daily.3

I usually start patients on 20 mg when I’m using this regimen because that’s the dose that was in the clinical trial [CLEAR; NCT02811861]….4 I find the toxicity management can be similar with the other regimens, but in general, there’s a linear pharmacokinetics with the IO [immuno-oncology] plus TKI [tyrosine kinase inhibitor], so higher dosing on a population level is best, and the trial started at 20 mg per day, so that’s where I start.

I do, however, give patients a heads-up, especially with this regimen, that over the first couple of months there might be some need for dose reductions, modifications, and breaks, and that it could take 3 to 6 months until we settle with a patient what the right dose is going to be and what the appropriate supportive care measures will be for them.

What is important to know about the dose modifications for lenvatinib?

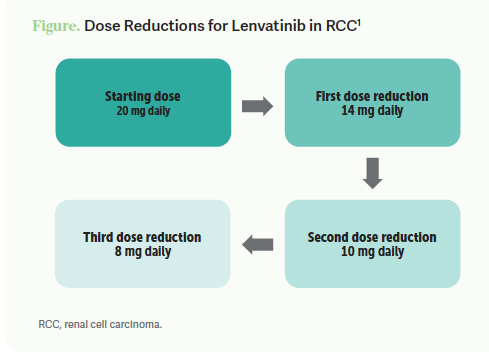

The dose reductions in the trial for 20-mg lenvatinib started with the first reduction to 14 mg, second reduction to 10 mg, and lastly to 8 mg [Figure1]. As with all the TKIs, the strategies for adverse event [AE] mitigation are withholding a couple of days of therapy, dose reducing if we can’t keep patients on the dose that they were previously on, or discontinuing lenvatinib as recommended.

One of the challenges patients run into with lenvatinib…is that lenvatinib comes in 10-mg tablets and 4-mg tablets. It’s important that if you’re going to drop a patient from 20 mg to 14 mg, you have to get them pills that are 4 mg. There is a dose exchange, so you or your nurse or somebody in the pharmacy…can just Google and fill out a form so that unused doses can be sent back to the company in exchange. Fifteen unused doses can be sent back for a lower dose, so that patients aren’t stuck without medications or having to absorb costs. One of the things that wasn’t mentioned in the decision between the IO/TKIs and ipilimumab [Yervoy] plus nivolumab is that people sometimes will have issues obtaining pills through specialty pharmacies, or they’re concerned about patient adherence with taking daily pills. [Physicians] may think giving the 2 intravenous medications is easier.

How tolerable is lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab, and how does it compare with the use of lenvatinib plus everolimus (Afinitor) in the refractory setting?

When we were using lenvatinib only with everolimus in the refractory setting, I found that sometimes we would go to the nurse practitioner and physician’s assistant and tell them that we were starting a patient on lenvatinib and everolimus and they would…say, “…we’re going to have to deal with all these AEs.” But that partially had to do with [the fact] that it’s given with everolimus in the third and fourth line where patients are more [ill]. [In the front line], for the most part, these patients will come into clinic feeling OK. I’ve also been pleasantly surprised with the AE profile, [although that’s] not to say we don’t have to dose reduce. I warn patients that up to 70% will require a dose reduction [Table 14]. But I find lenvatinib/pembrolizumab to be better tolerated than lenvatinib and everolimus, probably because it was [used in] a refractory population.

I [support] preparing the patient up front with all these regimens. I tell them, “The [overall] response rate for this regimen is over 70%. The disease control rate for this regimen is [approximately] 95%.4 But it will take time until we get to the right dose. Call in whenever there’s an issue.” They should know that for the first couple of months, there might be more contact points.

There might be more visits; there might be more phone calls. But usually I find once we get to 3 to 6 months into a regimen, we hit a steady state in terms of them being on the right regimen, the right dose, and with the right supportive care.

CASE UPDATE

- At 8 weeks

- Follow-up CT scan showed partial response

- 10 weeks after treatment initiation

- The patient contacted the office reporting at-home blood pressure recorded at 160/110 mm Hg.

- The following day, in-office blood pressure was 170/115 mm Hg.

- Antihypertensive therapy was initiated.

- Pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib was continued.

- Hypertension persisted despite up-titration of antihypertensive medication for 2 weeks.

- Lenvatinib was held, and blood pressure stabilized around 130 to 140 mm Hg/80 to 90 mm Hg on the antihypertensive .

- Lenvatinib was resumed at 14 mg daily.

Is this case reflective of your experience treating patients?

This is the common approach and the common paradigm of AEs with these medicines, where patients will have their first toxicity whether it’s diarrhea or hypertension; we institute some supportive care and continue them on the current dose. Then, if it persists and despite supportive measures cannot be reduced to a grade 1 AE, we hold, let it flush out of the system for a little bit, and then dose reduce.

Some [may] start the lenvatinib at a lower dose. I push back a little bit. If I think a patient can tolerate it, I give them the highest dose. I find it’s hard to ramp up. It’s hard to give a patient a 10-mg dose, [because then if] they’re doing pretty well, their scans are stable 3 months in and maybe with some tumor burden reduction, [it’s hard] to tell them we’re going to increase this medicine which might make you feel a little worse. I find that it’s easier psychologically, and maybe also medically, when they’re coming in with treatment-naive disease, to say, “We’re going to throw a big, heavy regimen [at you], and then we’ll peel off as necessary.”

Do you usually use the pembrolizumab dosage schedule of 200 mg every 3 weeks or 400 mg every 6 weeks?

I start every 3 weeks and I tell them I like having the touch point every 3 weeks. Then after the first scans I offer them the option to switch to every 6 weeks. Some patients do not want to be in the cancer center any more than they have to, so coming in every 6 weeks is a blessing. [Conversely], some patients never want to change if their disease became stable on a 3-week regimen. They just want to be seen every 3 weeks.

In the trial, it was 69% of patients who required a dose reduction I tell patients that despite the dose reductions in the trial, and despite the fact that up to [one-fourth] of patients actually had to stop lenvatinib, we see these benefits. If you compare [data] across the trials, the strongest responses, PFS [progression-free survival], and complete response [CR] rate are with this regimen.… If a patient is strong and willing to undergo it and trust us, I just give them the warning that there’s a good chance we’ll have to dose reduce, but we’ll take it one dose at a time.

How important is it to push for the highest tolerable dose of lenvatinib?

The primary reason [ for a higher dose] is with TKIs, there are linear pharmacokinetics. For the population at large, a higher dose translates into a higher plasma level and better efficacy. We’ve seen that…these regimens…at least presented the data that more substantial tumor burden reduction is associated with better outcomes. If you break it down into somebody whose tumor shrunk by 25% vs 50% vs 80%, vs a CR, once you hit about an 80% tumor burden reduction, it’s probably close enough to the equivalent of a CR.5-7 But there seems to be a benefit to obtaining a greater tumor burden reduction.

I was surprised to see those data the first time they were presented, because I often tell the patients that as long as the cancer is stable or it’s shrunk by 10%, at least it’s not growing, and that’s good. But we do have data now suggesting that the more of the cancer we can eliminate from the scans, [the better]. It’s intuitive, but I only think about that in [a disease like] chronic myeloid leukemia, where we can measure a minimal residual disease state. I never thought that could be the case in RCC. But now we have those data from all these trials that the deeper the tumor burden reduction, the better the long-term outcome. [However], it’s better to have a patient who has a 25% tumor burden reduction but can stay on therapy for a year rather than somebody who has a 75% tumor burden reduction but they can’t handle the therapy and they’ll progress that way.

What can we learn from the use of corticosteroids in the frontline RCC trials?

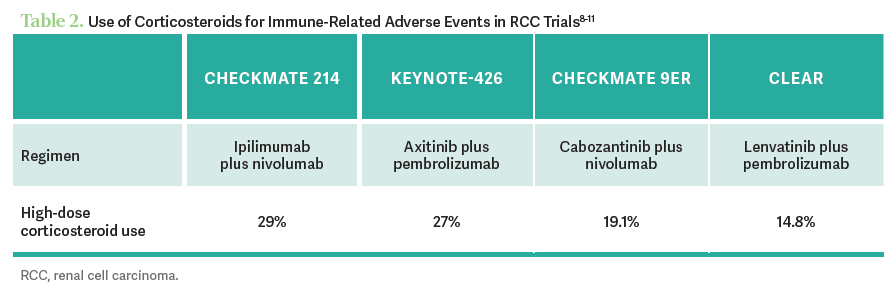

Looking at the steroid use, it was highest in the ipilimumab/nivolumab study. The next highest is in axitinib plus pembrolizumab, then cabozantinib plus nivolumab, and lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab was a bit lower...[Table 28-11]. I think the reason for that is that these trials were sequential, at least for the IO/TKIs. We expect the highest rate of immune-related AEs [irAEs] with ipilimumab/nivolumab. But in the other 3 regimens, I think we just got better at managing the toxicities and understanding what an IO toxicity is vs a TKI toxicity, and maybe [at] not pulling the trigger too quickly for steroids.

How do you identify toxicities associated with IO and TKI therapies?

It’s well established that there are certain toxicities that occur with the IO/IO regimen, in the sense that we know what the irAEs are. Then there are well-established toxicities that occur with the TKI such as mucositis, diarrhea, and hypertension. One thing that can be confusing is that there are overlapping toxicities as well. If a patient comes in with elevated liver function tests [LFTs] or diarrhea, it’s possible that it’s from the immunotherapy [or] the targeted therapy. It’s often a clinical dilemma to figure out which one is causing the toxicity.

Obviously, if the patients come in with significant toxicity that appears to be immune related, you start steroids and ask questions later. But there are times when a patient will come in with mild diarrhea or mildly elevated LFTs, and it could be from…the axitinib or it could be from the pembrolizumab. One very practical approach is to hold the TKI for a little while, and within a couple of days, if you hold the TKI, the diarrhea or the LFTs should get better. If they don’t, then it’s probably the immunotherapy.

REFERENCES:

1. Lenvima. Prescribing information. Eisai Inc; 2023. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://bit.ly/3MRDWXg

2. Cabometyx. Prescribing information. Exelixis, Inc; 2021. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://bit.ly/3Z8xpec

3. Inlyta. Prescribing information. Pfizer Inc; 2022. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://bit.ly/3y6GUyw

4. Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha SY, et al; CLEAR Trial Investigators. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(14):1289-1300. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035716

5. Plimack ER, Rini BI, Stus V, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib as first-line therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC): updated analysis of KEYNOTE-426. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(suppl 15). doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_ suppl.5001

6. Suárez C, Choueiri TK, Burotto M, et al. Association between depth of response (DepOR) and clinical outcomes: exploratory analysis in patients with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC) in CheckMate 9ER. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 16):4501. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.4501

7. Grünwald V, Powles T, Kopyltsov E, et al. Analysis of the CLEAR study in patients (pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC): depth of response and efficacy for selected subgroups in the lenvatinib (LEN)+ pembrolizumab (PEMBRO) and sunitinib (SUN) treatment arms. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):4560. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.4560

8. Albiges L, Tannir NM, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: extended 4-year follow-up of the phase III CheckMate 214 trial. ESMO Open. 2020;5(6):e001079. doi:10.1136/esmoopen-2020-001079

9. Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al; KEYNOTE-426 Investigators. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(12):1116-1127. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1816714

10. Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al; CheckMate 9ER Investigators. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):829-841. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2026982

11. Choueiri TK, Eto M, Kopyltsov E, et al. Phase III CLEAR trial in advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC): outcomes in subgroups and toxicity update. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(suppl 5):S683-S685. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.056

Enhancing Precision in Immunotherapy: CD8 PET-Avidity in RCC

March 1st 2024In this episode of Emerging Experts, Peter Zang, MD, highlights research on baseline CD8 lymph node avidity with 89-Zr-crefmirlimab for the treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and response to immunotherapy.

Listen

Beyond the First-Line: Economides on Advancing Therapies in RCC

February 1st 2024In our 4th episode of Emerging Experts, Minas P. Economides, MD, unveils the challenges and opportunities for renal cell carcinoma treatment, focusing on the lack of therapies available in the second-line setting.

Listen