Kulik Addresses Transplant and Therapy in HCC

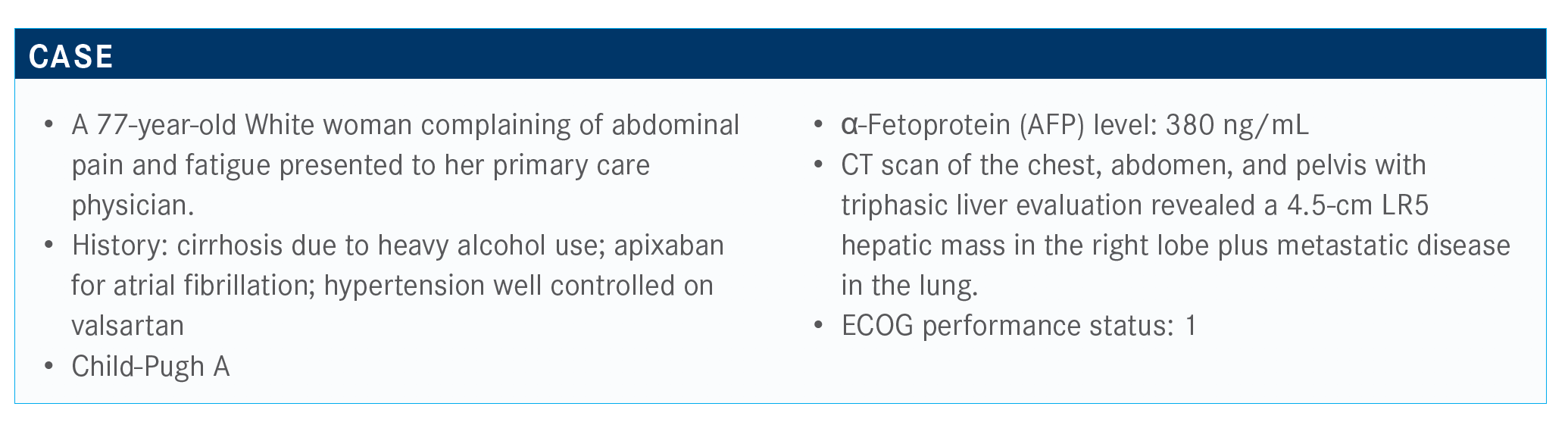

Laura M. Kulik, MD, talked through diagnosing a 77-year-old female patients with hepatocellular carcinoma as well as the treatment options for her disease during a Targeted Oncology Case Based Peer Perspectives event.

Laura M. Kulik, MD

Laura M. Kulik, MD, professor of Medicine (Gastroenterology and Hepatology), Radiology and Surgery (Organ Transplantation) at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, IL, talked through diagnosing a 77-year-old female patients with hepatocellular carcinoma as well as the treatment options for her disease during a Targeted Oncology Case Based Peer Perspectives event.

Targeted Oncology™: What is your initial impression of this case?

KULIK: Looking at this patient, she has metastatic disease and her age—as a hepatologist, the first things that I’m always running through in my mind are: Is this a surgical patient, [is there] the option for resection, and is this a transplant candidate? In this patient, the answer to these is clearly no.

Would you recommend a biopsy for this patient?

We are seeing a rise in cholangiocarcinoma, particularly among people who are older, and this patient is 77. She has risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma with scar tissue, including excessive alcohol use, hepatitis C virus [HCV], and hepatitis B [HBV].

We don’t do biopsies…in hepatology like we used to. We’re using noninvasive ways to assess whether someone has fibrosis. They may not be cirrhotic. We use things [such as] the Aspartate Aminotransferase [AST] to Platelet Ratio Index score, which looks at the AST and platelet ratio, the size of the spleen, the size of the portal vein, whether there’s presence of varices, et cetera. But it’s not always 100%, and about 25% of people who have a normal-appearing liver on an ultrasound may have underlying cirrhosis. And if someone does not have underlying cirrhosis—LI-RADS [Liver Reporting & Data System] is based on the presence of having cirrhosis—then a biopsy is required to make sure that this is indeed hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC].

LI-RADS keeps changing; it is a living document. If a patient’s reading on LI-RADS is 5, which meets the criteria of HCC, it is a

96% chance that [the] patient does indeed have HCC. But many people do feel strongly about proceeding with a biopsy; [it] may be helpful not only for the diagnosis but potentially prognosis and potentially treatment strategies.

There’s always been the fear of bleeding. This patient is on apixaban, so I would not biopsy without the risk-benefit ratio of being able to stop her anticoagulant. Then there’s the fear of seeding; this patient already has metastatic disease. In my practice, if this was a transplant candidate, we would not allow biopsies because [our past transplant surgeon] was fearful of needle track seeding, based on [more than] 25 years of [experience] and seeing a handful [of occurrences].

Would your use of a biopsy be different if the patient did not have cirrhosis? And would it be different if this were a LI-RADS 4?

If this patient didn’t have cirrhosis, there’s a potential that this could be another type of a lesion because the risk of HCC is not as high without underlying cirrhosis; about 90% of people with HCC will have advanced fibrosis. Some of the guidelines have changed. European guidelines recommend in people with advanced fibrosis, which is stage 3 and stage 4, to do screening. Whereas the American guidelines have stuck with having underlying cirrhosis.

We know that this carries about an 80% chance that this will be HCC. But, as we’ve spoken about, if it is cholangiocarcinoma, there would be differences in how we would approach this patient. Some will undergo locoregional therapy if this wasn’t metastatic disease. If it is a mixed tumor, I’ve generally seen the oncologist do systemic therapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin before using something like a tyrosine kinase inhibitor [TKI].

Assuming that the biopsy was obtained, and it does confirm that this is a diagnosis of HCC, would you suggest further genetic analysis of the biopsy tissue?

Next-generation sequencing has become, on most tumors, standard of care. This is not something, as a hepatologist, that we’re generally sending. We send this to oncology to deal with. I haven’t seen a ton in HCC because there [have] not been a lot of actionable mutations.

There have been some data from Harding et al that looked at that, where they did a prospective trial and they did genetic analysis of tumors.1 They were able to differentiate people who were more likely to have an [improved] overall survival [OS] when you looked at TKI versus immunotherapy, based on the type of mutation, if it was an PI3K-mTOR versus WNT/β-catenin pathway present. But, when they looked at the number of people who had an actionable mutation, which we know in HCC is low, it was consistent with what we see in the literature.

I think that patients like when there’s more information, when you tell them you’re going to be doing this to see whether there is something that can be done that is outside what we normally would do. There [have] been a lot of genetic analyses and publications that have looked at this on an RNA level, all different types, and there’s a percentage of patients with HCC who would respond to an IDO inhibitor. So I think it is worth doing it, even though the number of patients that we find that we can do something on is not as high as what we would like.

What do the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines suggest for patients in this setting?

For first-line therapy, there is no wrong answer.2 People can start with sorafenib [Nexavar], lenvatinib [Lenvima], or the combination therapy. There’s also a suggestion for nivolumab [Opdivo] monotherapy, or folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin in certain clinical circumstances.

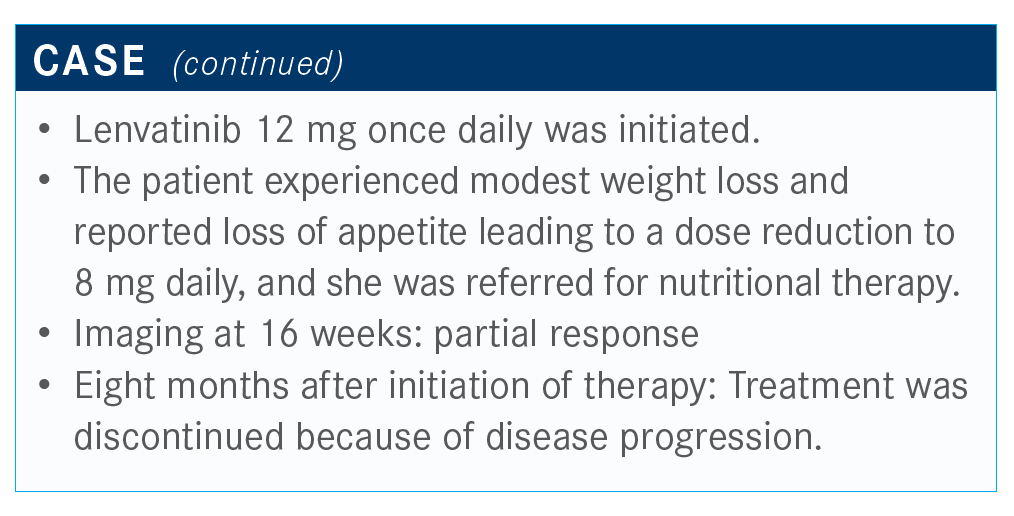

Are there adverse effects that affect your choice of lenvatinib or sorafenib in a patient?

[With lenvatinib], appetite, fatigue, and weight loss are what I have seen [most] in these patients because they are already sarcopenic, which has been found to be a risk factor for cirrhotic patients and in many chronic diseases. I found [appetite] is more [of a problem] with lenvatinib, but I have been using it more and more as opposed to sorafenib, also in combination with locoregional therapy.

In terms of using locoregional therapy, if the patient has new lesions develop within the liver or after a number of treatments, when would you switch to systemic therapy?

I’ve been at meetings where the interventional radiologists are overdoing transcatheter arterial chemoembolization or overdoing radioembolization, to the point that the patients are no longer Child-Pugh A, which is the context that all these registrations were in. Once they [progress to] Child-Pugh B or C, they have potentially lost the opportunity for an improvement in OS associated with systemic agents. Every patient needs to be looked at as an individual in terms of making those decisions.

All these trials [that we discussed] were in patients who were Child-Pugh A. We have some evidence from GIDEON, and there’s also been a recent meta-analysis looking at sorafenib, but for some of these newer drugs, we don’t have extended real-world experiences yet, in terms of using them in patients with more advanced disease.

How does the patient’s Child-Pugh classification affect your treatment?

Patients are always going to want to try something because we finally have some drugs that have [shown] activity, so they’re willing to try. But one of the things I always point out to patients when we first start talking about this is the unfortunate situation that there are 2 things working against them: their chances of dying of liver failure, if they’re not a transplant candidate, say in this patient due to age and advanced disease, versus dying of their liver cancer. The liver cancer may be causing the liver failure because of the amount of tumor burden that they have.

In someone who is Child-Pugh B, they have a 30% chance, without cancer, that they will die in the next year without a transplant. It is difficult to temper that with patients and say, “I can make your cancer look better, but you may die as a result of your liver disease first.”

Albumin-bilirubin [ALBI] is the newer classification that is gaining use as opposed to the Child-Pugh classification. It’s simple to use. You look at the bilirubin and the albumin levels. There’s a calculator; you put the 2 points together, and it tells you whether the patient is a 1, 2A, 2B, or 3. There’s been a lot of work that’s looked at this in systemic options as well as in locoregional therapy and resection to help guide how these patients are going to do. I think there’s going to be more real-world data that will come, particularly in combination therapy because of the risk of varices. I would be more afraid of using something with a combination such as bevacizumab [Avastin] in someone whose Child-Pugh classification is worsening because we know that their chances of bleeding increase as their Child-Pugh increases.

Do you use TKI as a monotherapy in the first line for your patients with advanced HCC?

I think that with the excitement of the checkpoint inhibitors and now with the combination therapy, people are using this more. Personally, if we see a patient who has a portal vein thrombus— not within the main portal vein or not involving both the right and the left—and they’re otherwise a good transplant candidate, I would [suggest] radioembolization for them and then likely start lenvatinib.

I choose lenvatinib over sorafenib because of the increase of response rates, which is what we need to see in order…for this person to potentially [be eligible for] transplant.

What do you consider to be the most important end points in selecting systemic therapy for patients?

I would say that of the many [advisory] boards that I’ve gone to say that survival is [most important], and safety and tolerability are [right behind that]. Response rate, I think, is important, depending on what your goal is for that patient. If you’re never going to get this patient to transplant or even resection, some centers will be aggressive and will resect if they treat and they have an increase in their [future liver remnant] and a response in the portal vein, as long as it’s not main portal vein, then they will consider doing a resection on that person. Response rate is important if that is one of the goals or potentials.

Does the etiology of the patient’s disease of HCV versus HBV make a difference in terms of treatment?

In both of these diseases, we have good antiretroviral therapies, so we can apply that to hopefully keep the liver function sustained, so that they can receive anticancer therapy for a longer period of time. There was a meta-analysis conducted that had shown a trend. It wasn’t significant, but there was a high trend in patients with HBV doing better with lenvatinib compared with sorafenib, but no difference in patients with HCV in terms of outcomes.3

This patient is not someone that [I would ever] downstage. I think it’s hard to not give patients a false sense that this could be something that could happen. At Northwestern Medicine, we’ve transplanted 5 people who have had nonmain portal vein thrombosis who have had a great response. There was a recent publication from Canada, as well as centers throughout the United States, that found the AFP level was a strong predictor. So, if it was less than 10 ng/mL and they had response in the portal vein, that these patients had OS of 5 years, I believe it was 60%.

If you had a patient who may potentially receive a transplant, what are your thoughts on using a checkpoint inhibitor?

In these patients, I have shied away from the use of a checkpoint inhibitor until we have more information. Patients who have been on immune checkpoint inhibitors will get a transplant with a great response. The question will be: Could you have not transplanted them, and they would have done fine because of the response that they had? Are they going to be at higher risk of graft loss as a result of rejection? It’s great that we have all these different treatments, but it also brings up additional questions.

What are the relevant data in this setting?

The SHARP trial [NCT00105443] was the first clinical trial that showed efficacy of a drug in HCC.4 These patients had no previous systemic treatment. They were randomized to sorafenib or placebo, with a primary outcome being OS and time to progression. This pivotal trial showed a significant improvement in OS, as well as an improvement in time to radiographic progression.

This led to the REFLECT study [NCT01761266], which was a head-to-head study looking at sorafenib versus lenvatinib.5 Lenvatinib was dosed according to patients’ weight, and sorafenib was the standard. Patients who had portal vein invasion that was main portal vein, or bile duct invasion, or greater than 50% of the liver were excluded from this study. OS was the primary end point.

This was designed as a noninferiority study. Lenvatinib numerically had better OS, at 13.6 months compared [with] 12.3 months [HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.79-1.06]. This was not significant, but it did meet the preassigned confidence interval of coming under 1.08 and therefore met its primary end point of noninferiority.

When you looked at things such as progression-free survival [PFS] and time to progression, as well as response rates, all of these were significantly improved in patients who received lenvatinib over sorafenib.

Lenvatinib is not inferior and had significant improvements and parameters such as time to progression and PFS.

References:

1. Harding JJ, Nandakumar S, Armenia J, et al. Prospective genotyping of hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical implications of next-generation sequencing for matching patients to targeted and immune therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(7):2116-2126. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2293

2. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hepatobiliary cancers, version 5.2020. August 4, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://bit.ly/2YGXWlA

3. Casadei Gardini A, Puzzoni M, Montagnani F, et al. Profile of lenvatinib in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: design, development, potential place in therapy and network meta-analysis of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in all phase III trials. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:2981-2988. doi:10.2147/OTT. S192572

4. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378-390. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708857

5. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163-1173. doi:10.1016/ S0140-6736(18)30207-1

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More