Druggable Targets Are Explored at ISGIO

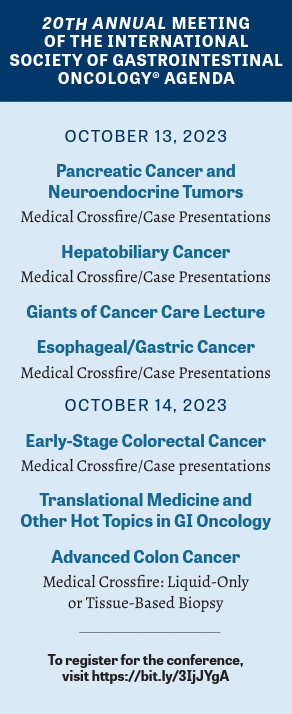

Druggable targets for patients with gastrointestinal cancers were discussed during the 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Gastrointestinal Oncology.

Tanios S. Bekaii-Saab, MD

One benefit attendees of the 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Gastrointestinal Oncology® (ISGIO) will experience is that by October, the data presented at similar meetings earlier in the year will have percolated through to their diagnostic and therapeutic workup routines.

“During the conference, those data are formatted and organized [in a way] that is friendly to clinical practice,” conference cochair Tanios S. Bekaii-Saab, MD, said in in a preconference interview with Targeted Therapies in Oncology. “The goal of ISGIO is not only to present the most up-to-date, cutting-edge information, but to ensure that it’s relevant to day-to-day practice.”

The Emergence of Druggable Targets

The first session, which will be held on October 13, 2023, will focus on pancreatic adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine neoplasms, challenging cancers for which there used to be few druggable targets. Ongoing research, however, suggests that breaking the disease into subgroups may lead to promising therapy.

“One of those rare alterations is KRAS G12C,” Bekaii-Saab said, “which [for years] was not druggable but now [is],” adding that the KRAS inhibitors that have shown promise in lung cancer are now undergoing evaluation in pancreatic cancer.

Findings from the phase 1/2 CodeBreak 100 study (NCT03600883) demonstrated that sotorasib (Lumakras) had clinically meaningful anticancer activity plus a positive risk-benefit profile in patients with KRAS G12C–mutated advanced pancreatic cancer.1 In the phase 1 portion of the trial, the primary objective was to determine safety and identify a recommended dose for phase 2. In phase 2, patients received 900 mg of sotorasib once daily.

Thirty-eight patients pooled from phases 1 and 2 received sotorasib, and a total of 8 patients had a confirmed objective response of 21% (95% CI, 10%-37%). Investigators reported that the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 4.0 months (95% CI, 2.8-5.6) and the median overall survival (OS) was 6.9 months (95% CI, 5.0-9.1). In addition, median treatment duration was 4.1 months, and median follow-up was at 16.8 months.2

Regarding safety, Strickler et al reported that 16 patients (42%) experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) of any grade and 6 (16%) had grade 3 adverse events. No TRAEs were fatal or led to treatment discontinuation.1

Even as investigators explore this potential treatment, others are looking to move beyond KRAS G12C. “Patients with the KRAS G12C alteration make up a small subset, so how do we help patients whose tumors are KRAS G12D— or KRAS G12V–mutated?” asked Bekaii-Saab. “That will be a key point in our discussions during the presentation.”

Turning to neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), Bekaii-Saab said that the challenge will be exploring new approaches. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) has been as an option in the metastatic, or nonresectable settings. Evidence for the antitumor effect of PRRT had been largely obtained from nonrandomized phase 2 trials or retrospective studies, but the NETTER-1 phase 3 trial (NCT01578239) confirmed its efficacy and low toxicity.3

The 229 patients in NETTER-1, who all had well-differentiated metastatic midgut NETs, received either 177Lu-Dotatate (n = 116) plus best supportive care, including octreotide long-acting repeatable (LAR), or octreotide LAR alone (n = 113).

The primary end point was PFS, and the secondary end points were objective response rate (ORR), OS, safety, and adverse event profile.

Rate of PFS at 20 months was 65.2% (95% CI, 50.0%-76.8%) in the treatment arm and 10.8% (95% CI, 3.5%-23.0%) in the control arm. Investigators reported an ORR of 18% in the treatment arm and 3% in the control arm (P < .001).3

Fourteen patients in the treatment group and 26 in the control group died during the planned interim analysis (P = .004).3

For both malignancies, researchers “want to discuss the advancements that are happening in real time, but also…solutions that take into account the diverse population,” Bekaii-Saab emphasized.

The Rise of Variants

In colorectal cancer (CRC), targeted approaches are on the rise, making testing for variants all the more important. However, Bekaii-Saab pointed out that the 4 most relevant clinical testing targets are HER2 expression, BRAF and RAS mutations, and microsatellite (MSI) status.

“The rationale is that MSI status would help you determine if immunotherapy is an option, HER2 amplifications could help exclude patients from receiving EGFR inhibitors, as would BRAF and RAS mutations. A RAS mutation could also determine if the patient has a KRAS G12C mutation,” he said.

The KRAS G12C inhibitor adagrasib (Krazati) demonstrated a disease control rate (DCR) of 100% in patients with gastrointestinal (GI) cancers in the KRYSTAL-1 trial (NCT03785249).4 The phase 1/2 study evaluated patients with advanced solid tumors that harbored a KRAS G12C mutation. Previously treated patients with unresectable or metastatic solid tumors, excluding non–small cell lung cancer and CRC but including pancreatic and other GI cancers, received 600 mg of sotorasib.

In the preliminary analysis, 27 patients with GI tumors were evaluated for clinical activity. Forty-one percent (n = 11/27) had a partial response. Among patients with pancreatic cancer (n = 12), 10 were evaluable for clinical activity, with half demonstrating a partial response (PR). In this subpopulation, median PFS was 6.6 months (95% CI, 1.0-9.7), and treatment was ongoing in half the patients.

In the overall cohort, 90.5% (n = 38/42) of patients experienced a TRAE of any grade, and the most commonly reported were nausea (48%), diarrhea (43%), vomiting (43%), and fatigue (29%).

The Challenges We Face

Keeping up with variants and markers is a challenge for some community oncologists. According to Bekaii-Saab, “It’s standard to determine MSI status, to [test for] RAS, but I do see some BRAF tests that are missed, and HER2 amplification is an emerging target.… Community oncologist[s]…need to understand that these [variants and markers] will help them decide if a candidate should be receiving an EGFR inhibitor.”

Another challenge is logistical in nature, Bekaii-Saab said, particularly getting tumor tissue tested and the results back in a timely manner. “What I do is order a liquid biopsy and simultaneously obtain a tissue sample,” he explained. “I’ll receive the liquid biopsy results back in a week and if cancer cells are not present…, then it’s not in the tissue; if cancer cells are present in liquid, they will also be present in tissue.”

Although targeted therapies hold promise for a small subset of patients with GI cancers, the vast majority do not benefit, so one of the biggest challenges remaining is to expand benefits to most patients.

Whether that is accomplished by breaking down patients into smaller and smaller subgroups or by identifying better biomarkers, we don’t yet know.

Bekaii-Saab’s take-away message is that the treatment paradigm continues to shift and they should adapt to that shift in their clinical practice. “We want to excite clinicians about what’s coming next, and we want them to consider clinical trial enrollment that eventually leads to advancing care,” he concluded.

REFERENCES

1. Strickler JH, Satake H, George TJ, et al. Sotorasib in KRASp.G12C-mutated advanced pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):33-43. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2208470

2. Strickler JH, Satake H, Hollebecque A, et al.First data for sotorasib in patients with pancreatic cancer with KRASp.G12C mutation: a phase I/II study evaluating efficacy and safety. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 36):360490-360490. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.36_suppl.360490

3. Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, et al; NETTER-1 Trial Investigators. Phase 3 trial of 177 Lu-dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:125-135. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1607427

4. Bekaii-Saab TS, Spira AI, Yaeger R, et al.KRYSTAL-1: Updated activity and safety of adagrasib (MRTX849) in patients (Pts) with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer (PDAC) and other gastrointestinal (GI) tumors harboring a KRAS G12C mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 4):519- 519. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.4_suppl.519