Despite Shortcomings, Key Learnings Gleaned From Phase 3 Trials

Several studies with data released or presented in 2022 did not meet the threshold for significance or achieve their primary end points. Although such results are disappointing, takeaways from the trials can be used by the field as a whole to improve clinical trial design and achieve greater success in the future.

Oncologists often anticipate the results of large, randomized phase 3 clinical trials to learn how they might affect the oncology treatment landscape going forward. Not all studies, however, have an immediate practice-changing impact.

Several studies with data released or presented in 2022 did not meet the threshold for significance or achieve their primary end points. Although such results are disappointing, takeaways from the trials can be used by the field as a whole to improve clinical trial design and achieve greater success in the future with these agents and in each respective tumor type.

Many of the findings from phase 3 clinical trials that did not meet their primary end point in 2022 indicate that additional benefit could be seen with improved patient selection, a greater understanding of the tumor microenvironment and how different treatment modalities work together, and an increased focus on certain biomarker-driven groups.

This article will examine several such trials in 6 cancer types: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), prostate cancer, renal cell carcinoma (RCC), urothelial carcinoma, small cell lung cancer (SCLC), and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

HNSCC constitutes more than 90% of all head and neck cancers, is the sixth most common cancer worldwide, and most commonly affects the oral cavity, oropharynx, and larynx.1 The standard of care for locally advanced HNSCC is chemoradiation therapy (CRT) or surgery followed by radiation, with or without chemotherapy.2 PD-L1 is highly expressed in HNSCC tumors,3 and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), with or without chemotherapy, is approved in multiple indications for this patient population but not for a locally advanced indication.4

KEYNOTE-412 (NCT03040999), a randomized, double-blind phase 3 study, evaluated the efficacy and safety of adding pembrolizumab to CRT followed by pembrolizumab maintenance compared with placebo in 804 patients with treatment-naïve, unresected locally advanced HNSCC. Patients had p16-positive (any T4 or N3) oropharyngeal SCC, p16-negative (any T3-T4 or N2a-N3) oropharyngeal SCC, or larynx/ hypopharynx/oral cavity (any T3-T4 or N2a-N3) SCC.5 The rationale for conducting the study was a combination of the demonstrated efficacy of pembrolizumab in the recurrent and/or metastatic setting and initial safety results from a phase 1b trial (NCT02586207) of pembrolizumab plus CRT in the locally advanced setting.5

Primary results from KEYNOTE-412 showed a favorable trend toward improved event-free survival (EFS), the primary end point of the trial, with a 24-month EFS rate of 63.2% for pembrolizumab vs 56.2% for placebo, and rates of 57.4% and 52.1%, respectively, at 36 months. The median EFS was not reached in the pembrolizumab arm compared with 46.6 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.68-1.03; P = .0429). However, it did not reach statistical significance (superiority threshold, 1-sided P = .0242).6

During the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2022, discussant James Larkin, MD, suggested the treatment schedule and the combination of checkpoint inhibition with lymph node radiation therapy as potential reasons for the lack of statistical significance in the trial.

"Could there be an issue here with treatment schedule? An example and a comparison might be with the PACIFIC study [NCT02125461] in non– small cell lung cancer, which is a positive study where actually the checkpoint inhibition with durvalumab [Imfinzi] was given immediately after the chemoradiotherapy, leading to benefit, rather than [concurrently],” Larkin explained, adding that “a better understanding of integrating checkpoint inhibitors with radiotherapy in terms of timing, fields, dose, and fractionation is needed in this setting.” Larkin is a consultant medical oncologist and lead for the Uncommon Cancers Theme at The Royal Marsden BiomedicalResearch Centre at Institute of Cancer Research in London.

In addition, evidence from a post hoc analysis of KEYNOTE-412 suggests that PD-L1 expression may be a predictive biomarker of treatment with PD-1 inhibitors. EFS rates were similar among those with a PD-L1 combined positive score of at least 1, with a 24-month EFS rate of 63.7% with pembrolizumab and 56.3% with placebo and 36-month rates of 58.0% and 51.8%, respectively (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.64-1.00). However, more of a difference was seen in EFS rates in those with PD-L1 expression of at least 20 by combined positive score. The EFS rate at 2 years was 71.2% with pembrolizumab vs 62.6% with placebo, and at 3 years, the rates were 66.7% and 57.2%, respectively (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.49-1.06).6

Despite a trend favoring the pembrolizumab arm in the intention-to-treat and PD-L1–positive populations, KEYNOTE-412, shouldn’t be considered as an indication to use anti–PD-1 therapy with chemoradiotherapy across patient groups, said Kevin Harrington, PhD, head of the Division of Radiotherapy and Imaging and a team leader at the Institute of Cancer Research, after findings were presented at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2022. Rather, given the shortcomings reported from the JAVELIN HEAD AND NECK 100 [NCT02952586], REACH [NCT02999087], and PembroRad [NCT02707588] trials, a focus on designing optimal combination regimens might be a useful strategy, said Harrington.

Prostate Cancer

Despite significant recent advances in the treatment of patients with metastatic prostate cancer, the disease remains incurable, and more effective therapies are needed, especially for heavily pretreated patients.7 Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend microsatellite instability (MSI) testing for patients with metastatic castration- resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) and pembrolizumab therapy for patients with refractory MSI-high, mismatch repair–deficient, or tumor mutational burden–high (≥ 10 mutations/megabase) mCRPC.8 However, outside these select patients, pembrolizumab has not tended to show signifi cant benefit in prostate cancer.

KEYLYNK-010 (NCT03834519), a randomized, open-label phase 3 trial, evaluated the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab plus olaparib (Lynparza), a PARP inhibitor, compared with either abiraterone acetate Zytiga) or enzalutamide (Xtandi) in patients with mCRPC who were unselected for homologous recombination repair defects and progressed after treatment with chemotherapy and either abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide. The study was stopped for futility after the second prespecifi ed interim analysis based on guidance from the external data monitoring committee because it failed to show a statistically significant improvement in radiographic progression-free survival (4.4 for pembrolizumab + olaparib vs 4.2 months for abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide; HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82-1.25; P = .55) or overall survival (OS; 15.8 months vs 14.6 months, respectively; HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.77-1.14; P = .26).9

ESMO Congress discussant Martijn Lolkema, MD, said the trial highlighted the importance of patient selection because pembrolizumab is typically more beneficial in a biomarker-selected population for prostate cancer than in an unselected group of patients. Additionally, the late-stage setting after patients have already received novel hormonal therapy and chemotherapy may be a challenging population in which to test new treatment options.

Lolkema added that giving abiraterone acetate to patients who had already received enzalutamide and giving enzalutamide to patients who had received prior abiraterone acetate made for an interesting control arm. He suggested that cabazitaxel (Jevtana) or lutetium Lu 177 vipivotide tetraxetan (Pluvicto) be used as control arms in the future.

Renal Cell Carcinoma

Approximately 80% of patients with RCC are diagnosed with locoregional disease, with 5-year recurrence rates ranging from 10% in patients with low-risk disease to 68% in patients with high-risk disease.10 The standard of care for locoregional RCC is partial or radical nephrectomy, and adjuvant treatment with pembrolizumab or sunitinib malate (Sutent) is recommended for some patients.11-13 However, the use of adjuvant targeted therapy in RCC is infrequent, and adjuvant RCC trials to date have delivered mixed results.14

IMmotion010 (NCT03024996), a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase 3 trial, evaluated whether adjuvant atezolizumab (Tecentriq) could delay RCC recurrence following resection in high-risk patients compared with placebo. The rationale for the study was the effectiveness of PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies in combination with CTLA-4– or VEGF-targeting agents in the first-line metastatic setting, the approved use of pembrolizumab in the adjuvant setting, and atezolizumab’s efficacy in other cancers. The primary end point of the study was investigator-accessed disease-free survival (DFS).14

Findings from IMmotion010 showed no evidence of improved clinical outcomes with atezolizumab for patients with locoregional RCC. The median investigator-assessed DFS for atezolizumab was 57.2 months and 49.5 months with placebo, which was not considered statistically significant (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.75-1.15; P = .50). DFS rates at 3 years were similar between the 2 arms at 59.4% with atezolizumab and 59.0% with placebo. No significant difference in DFS was seen between the 2 groups, even among patients with positive or high PD-L1 expression.14

The study authors noted slight differences between the patient populations in IMmotion010 and KEYNOTE-564 (NCT03142334)—the trial that led to the approval of adjuvant pembrolizumab— including a higher percentage of patients with M1 no evidence of disease and patients with metachronous disease in the IMmotion010 study. These patients did not benefit from adjuvant atezolizumab, whereas those in the KEYNOTE-564 study with M1 no evidence of disease did achieve benefit.14,15

Why? ESMO Congress discussant Thomas Powles, MD, MBBS, MRCP, suggested there could be a difference in the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors (ie, pembrolizumab) vs PD-L1 inhibitors (ie, atezolizumab) on locally advanced RCC because anti–PD-L1 antibodies have tended to be less active in clear cell RCC.

For patients with intermediate- or poor-risk advanced RCC, nivolumab (Opdivo) plus ipilimumab (Yervoy) is a preferred frontline treatment option.13,16,17 CheckMate 914 (NCT03138512), a randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial, examined whether the combination (part A) or nivolumab monotherapy (part B) could benefit patients with stage II or III RCC at high risk for relapse following resection.17

Findings did not show a significant difference in DFS, the primary end point of the trial, for the immunotherapy combination vs placebo. The median DFS with nivolumab and ipilimumab was not reached compared with 50.7 months with placebo (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.71-1.19), which was not considered statistically significant (P = .5347). At 2 years, the DFS rates were 76.4% with the combination vs 74.0% with placebo. Additionally, a high degree of discontinuation was seen in the investigational arm due to treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs).17

According to the subgroup analysis, patients with pT2a (HR, 0.66), pT4, or N1 M0 disease (HR, 0.61) tended to benefit more from dual immune checkpoint inhibition than placebo, and so did those with sarcomatoid features (HR, 0.29), although this was a small patient subgroup.17

Regarding the high rate of discontinuation in the combination arm, Larkin said after presentation of data during the discussant portion at the ESMO Congress that better patient selection may have determined who could benefit from an anti–CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) in addition to an anti–PD-1 (nivolumab) to balance the additional toxicity. He also noted that approximately 23% of patients in the investigational arm received steroids for adverse events, which could have affected the efficacy of the regimen.

When comparing CheckMate 914 with KEYNOTE-564, Larkin noted that the patient population was similar between the 2 studies but that the duration of treatment was longer in the KEYNOTE-564 study.

Urothelial Carcinoma

Pembrolizumab monotherapy is a standard of care for patients with previously untreated urothelial cancer who are unable to receive platinum-based chemotherapy.4

LEAP-011 (NCT03898180), a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, global phase 3 trial, tested whether the addition of lenvatinib (Lenvima) to pembrolizumab would improve outcomes for patients with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer in the first-line setting who are cisplatin ineligible with tumors expressing PD-L1 or ineligible to receive any platinum-based chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 status.18 The combination of lenvatinib, a potent multiple-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and pembrolizumab showed promising efficacy and manageable safety in previously treated patients with urothelial carcinoma, regardless of PD-L1 status, in the phase 1b/2 KEYNOTE-146 trial (NCT02501096).18,19

However, in LEAP-011, the addition of lenvatinib did not result in an improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) or OS, the trial’s primary outcome measures. The median PFS in the pembrolizumab-lenvatinib arm was 4.5 months vs 4.0 months with pembrolizumab and placebo (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.72-1.14). The median OS in the combination arm was 11.8 months and 12.9 months in the pembrolizumab monotherapy arm (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.87-1.48). The objective response rate (ORR) was 33.1% with the doublet vs 28.9% with pembrolizumab, and the median duration of response (DOR) was 12.8 months and 19.3 months, respectively.20

TRAEs occurred in 86.9% of patients in the doublet arm and 67.1% of patients in the pembrolizumab monotherapy arm, and grade 3 to 5 TRAEs occurred in 50.0% and 27.9%, respectively. Six patients (2.8%) in the combination arm and 1 patient (0.5%) in the pembrolizumab arm died from a TRAE.20 The investigators noted that the safety profile of pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib was consistent with previous studies and no new safety signals were observed.

Regarding the conclusion that the benefit/risk ratio for lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab was not positive,20 the study authors suggested that the frail patient population may have been a factor. All patients had advanced disease, were ineligible for platinum chemotherapy, and most had an ECOG performance status of 2 and visceral disease.

Small Cell Lung Cancer

Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide (CE) is the recommended first-line treatment for patients with extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC).21 However, most patients eventually experience disease progression, requiring a new generation of effective therapies.22

T-cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif domains (TIGIT) is a newly described inhibitory immune checkpoint present on activated T cell and natural killer cells.23,24 Tiragolumab is an investigational, fully human, anti-TIGIT monoclonal antibody that has showed potential synergistic enhancement of immune-mediated tumor rejection.23,25-27 For example, in the phase 2 CITYSCAPE trial (NCT03563716), the combination of tiragolumab and atezolizumab led to a clinically meaningful improvement in ORR and PFS compared with atezolizumab alone in patients with chemotherapy-naïve, PD-L1–positive recurrent or metastatic NSCLC.28

SKYSCRAPER-02 (NCT04256421), a randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled phase 3 study, evaluated whether the combination of atezolizumab plus CE could be enhanced by adding tiragolumab in patients with ES-SCLC. Although tiragolumab was well tolerated, it did not provide additional benefit in PFS or OS. The median PFS in the full analysis set, which included patients with a history or presence of brain metastases, was 5.1 months with the tiragolumab regimen compared with 5.4 months with atezolizumab and CE alone (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.89-1.31). The interim OS in the full analysis set was 13.1 months with the addition of tiragolumab and 12.9 months without (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.80-1.30). Similar PFS and OS outcomes were seen in the primary analysis set of patients without brain metastases. The ORR was 70.8% with added tiragolumab and 65.6% without, with median DORs of 4.2 months and 5.1 months, respectively.22

The study authors suggested that perhaps TIGIT was not effective in ES-SCLC. However, Chandra P. Belani, MD, a discussant at the 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting where the SKYSCRAPER-02 findings were presented, suggested that patient selection based on PD-L1 expression or molecular subtype could have helped and possibly led to more benefit being shown in the experimental arm.

Charles M. Rudin, MD, PhD, presented the findings at ASCO and suggested that the triplet regimen from the placebo group is safe to use in patients with asymptomatic brain metastases. Rudin, chief of the Thoracic Oncology Service, codirector of the Fiona and Stanley Druckenmiller Center for Lung Cancer Research, and the Sylvia Hassenfeld Chair in Lung Cancer Research at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, added that data from the study support that patients with asymptomatic brain metastases can be treated with first-line systemic therapy even without receiving brain radiation therapy upfront.

Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer

Canakinumab (Ilaris) is a high-affinity human monoclonal antibody targeting IL-1β, and is approved for the treatment of some autoimmune disorders.29 An exploratory analysis of the CANTOS trial (NCT01327846) showed a significant reduction in NSCLC incidence and mortality in patients treated with canakinumab.30 However, neither the phase 3 CANOPY-1 trial (NCT03631199) nor the phase 3 CANOPY-2 trial (NCT03626545) showed benefit for canakinumab in patients with advanced NSCLC.31,32

CANOPY-A (NCT03447769), a randomized, double-blind phase 3 trial of patients with completely resected stage IIA to IIIB NSCLC who had received adjuvant cisplatin- based chemotherapy (if applicable) and thoracic radiotherapy (if applicable) evaluated the efficacy and safety of canakinumab following standard therapy vs placebo. The study found no significant benefit in DFS, with a median DFS of 35.0 months with canakinumab vs 29.7 months with placebo (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.78-1.14; 1-sided P = .258), and no meaningful differences between the 2 arms on subgroup analysis.33

“The role of inflammation in lung cancer has been long studied, but to date, it has not been effectively therapeutically harnessed," Edward B. Garon, MD, MS, said during his presentation of the CANOPY-A data at the ESMO Congress 2022.

Garon, a professor of medicine at Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA in Los Angeles, California, noted the excitement about IL-1β during the readout and concluded that “evaluation of biomarker data from the entire CANOPY program...will continue to be evaluated to try and further elucidate the role of IL-1β in NSCLC.”

Implications for Clinical Practice

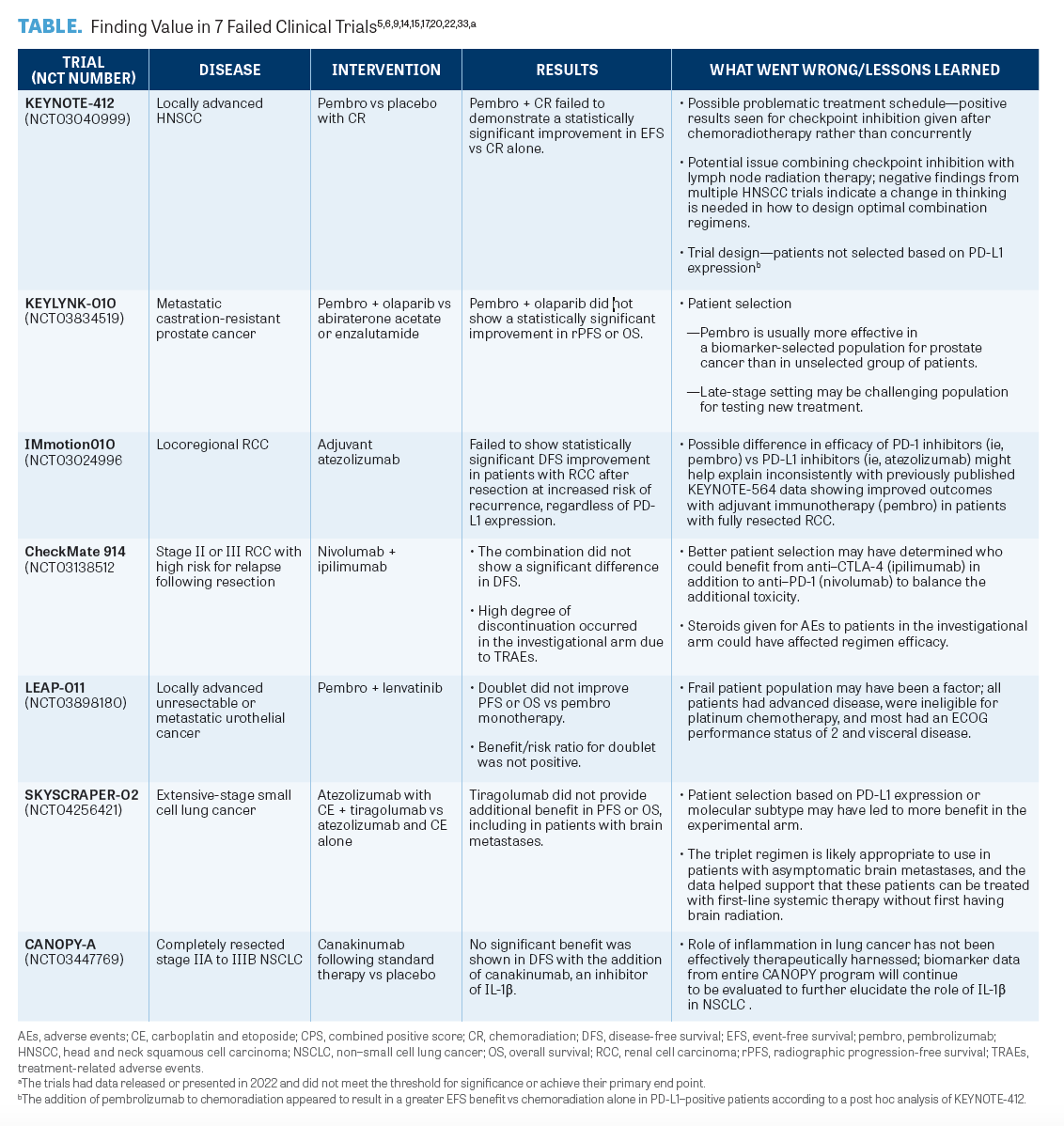

The pace of research in oncology has been accelerating, especially with the development of targeted agents. From 2006 to 2014, the number of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of combination therapy including immune checkpoint inhibitors more than tripled.34,35 Of note, the overall failure rate of oncological RCTs is higher than in other medical disciplines,36 leading to both clinical and financial toxicity.37 Some of the failures could stem from accelerated transition to phase 3 studies of agents that show some activity in preclinical or phase 1 studies in an attempt to accommodate the rapid development that patients seek. There is, however, value to be found in the failures (TABLE 5,6,9,14,15,17,20,22,33).

Conversely, successful late-phase RCTs rely on the identification of key on-target and off-target effects, dosing, and pharmacologic properties during preclinical and early clinical studies. Furthermore, biomarker identification can significantly contribute to the selection of tumor types in which new agents will be successful. Therefore, there is an argument for optimizing the design of clinical trials and raising the bar for initiating phase 3 RCTs.37 This view was echoed by Rafael Santana-Davila, MD, an associate professor of medicine and oncology at the University of Washington School of Medicine and an associate professor in the Clinical Research Division at Fred Hutch, in an interview with Targeted Therapies in Oncology™.

Santana-Davila’s advice for community oncologists deciding whether to enroll a patient on a clinical is to look at the activity of that drug as a single agent.

“Does it have activity as a single agent? If it [does], and your patient has that same disease, it’s very reasonable to pair it with the standard of care. If the agent has not ever been used as a single agent or has no activity as a single agent, the chances that it will work when you pair it to the standard care [are] likely to be [slim],” Santana-Davila said, adding that it is very possible that the results from ongoing RCTs will completely change the oncology treatment landscape in the next 12 months to 2 years.

Indeed, there are many exciting developments in the oncology pipeline and there is much to be learned from recent trials, even the unsuccessful ones.

Failed trials, though disappointing, still provide valuable information and crucial lessons that will ultimately lead to a greater understanding of the tumor microenvironment, biomarker and patient selection, and clinical trial design for the future.

REFERENCES:

1. Vigneswaran N, Williams MD. Epidemiologic trends in head and neck cancer and aids in diagnosis. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2014;26(2):123-141. doi:10.1016/j. coms.2014.01.001

2. Gregoire V, Lefebvre JL, Licitra L, Felip E, Group E-E-EGW.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: EHNS-ESMO- ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 5):v184-v186. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq185

3. Lyford-Pike S, Peng S, Young GD, et al. Evidence for a role of the PD-1:PD-L1 pathway in immune resistance of HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73(6):1733-1741. doi:10.1158/0008-5472. CAN-12-2384

4. Keytruda. Keytruda (pembrolizumab) prescribing information. Merck; 2014. Updated August 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://bit.ly/3VUGtl8

5. Machiels JP, Tao Y, Burtness B, et al. Pembrolizumab given concomitantly with chemoradiation and as maintenance therapy for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: KEYNOTE-412. Future Oncol. 2020;16(18):1235-1243. doi:10.2217/fon-2020-0184

6. Machiels JP, Tao Y, Burtness B, et al. LBA5 - Primary results of the phase III KEYNOTE-412 study: pembrolizumab (pembro) with chemoradiation therapy (CRT) vs placebo plus CRT for locally advanced (LA) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Ann Oncol. 2022;33(suppl_ 7):S808-S869. doi:10.1016/annonc/annonc1089

7. Yamada Y, Beltran H. The treatment landscape of metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2021;519:20-29. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2021.06.010

8. NCCN. NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2023. Prostate cancer. Updated September 16, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://bit.ly/3F4VCt0

9. Yu EY, Park SH, Goh JCH, et al. 1362MO - Pembrolizumab + olaparib vs abiraterone (abi) or enzalutamide (enza) for patients (pts) with previously treated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): randomized open-label phase III KEYLYNK-010 study. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(suppl 7):S616-S652. doi:10.1016/annonc/annonc1070

10. Lam JS, Leppert JT, Figlin RA, Belldegrun AS. Role of molecular markers in the diagnosis and therapy of rena cell carcinoma. Urology. 2005;66(suppl 5):1-9. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.112

11. Powles T, Albiges L, Bex A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline update on the use of immunotherapy in early stage and advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(12):1511-1519. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.09.014

12. Ljungberg B, Albiges L, Abu-Ghanem Y, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2022 update. Eur Urol. 2022;82(4):399-410. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2022.03.006

13. NCCN. NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2023. Kidney cancer. Updated September 22, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://bit.ly/2TAx1m3

14. Pal SK, Uzzo R, Karam JA, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab versus placebo for patients with renal cell carcinoma at increased risk of recurrence following resection (IMmotion010): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10358):1103-1116. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01658-0

15. Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al; KEYNOTE-564 Investigators. Adjuvant pembrolizumab after nephrectomy in renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(8):683-694. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2106391

16. Opdivo. Opdivo (nivolumab) prescribing information. Bristol Myers Squibb; 2014.Updated May 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://bit.ly/3W3faFi

17. Motzer RJ, Russo P, Grünwald V, et al. LBA4 - Adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus placebo for localized renal cell carcinoma at high risk of relapse after nephrectomy: results from the randomized, phase 3 CheckMate 914 trial. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(suppl 7):S808-S869. doi:10.1016/annonc/annonc1089

18. Loriot Y, Balar AV, Wit RD, et al. 2253 - Phase 3 LEAP-011 trial: first-line pembrolizumab with lenvatinib in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma ineligible to receive platinum-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 5):v356-v402. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdz249

19. Taylor MH, Lee CH, Makker V, et al. Phase IB/II trial of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, endometrial cancer, and other selected advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(11):1154-1163. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.01598

20. Loriot Y, Grivas P, Wit RD, et al. First-line pembrolizumab (pembro) with or without lenvatinib (lenva) in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma (LEAP-011): a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 6):432. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.6_suppl.432

21. NCCN. NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2023. Small cell lung cancer. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://bit.ly/2JTv4zC

22. Rudin CM, Liu SV, Lu S, et al. SKYSCRAPER-02: primary results of a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled study of atezolizumab (atezo) + carboplatin + etoposide (CE) with or without tiragolumab (tira) in patients (pts) with untreated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 17):LBA8507.

doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.17_suppl.LBA8507

23. Johnston RJ, Comps-Agrar L, Hackney J, et al. The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8(+) T cell effector function. Cancer Cell. 2014;26(6):923-937. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2014.10.018

24. Yu X, Harden K, Gonzalez LC, et al. The surface protein TIGIT suppresses T cell activation by promoting the generation of mature immunoregulatory dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(1):48-57. doi:10.1038/ni.1674

25. Sanchez-Correa B, Valhondo I, Hassouneh F, et al. DNAM-1 and the TIGIT/PVRIG/TACTILE axis: novel immune checkpoints for natural killer cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(6):877. doi:10.3390/cancers11060877

26. Stanietsky N, Simic H, Arapovic J, et al. The interaction of TIGIT with PVR and PVRL2 inhibits human NK cell cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(42):17858-17863. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903474106

27. Kurtulus S, Sakuishi K, Ngiow SF, et al. TIGIT predominantly regulates the immune response via regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(11):4053-4062. doi:10.1172/JCI81187

28. Cho BC, Abreu DR, Hussein M, et al. Tiragolumab plus atezolizumab versus placebo plus atezolizumab as a first-line treatment for PD-L1-selected non-small-cell lung cancer (CITYSCAPE): primary and follow-up analyses of a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(6):781-792. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00226-1

29. Dhimolea E. Canakinumab. MAbs. 2010;2(1):3-13. doi:10.4161/mabs.2.1.10328

30. Wong CC, Baum J, Silvestro A, et al. Inhibition of IL1β by canakinumab may be effective against diverse molecular subtypes of lung cancer: an exploratory analysis of the CANTOS trial. Cancer Res. 2020;80(24):5597-5605. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.Can-19-3176

31. Tan DSW, Felip E, Castro Jr G, et al. Canakinumab in combination with first-line (1L) pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for advanced non‑small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC): results from the CANOPY-1 phase 3 trial. Presented at 2022 American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting; April 8-13, 2022. Abstract CT037.

32. Paz-Ares L, Goto Y, Lim WDT, et al. 1194MO - Canakinumab (CAN) + docetaxel (DTX) for the second- or third-line (2/3L) treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): CANOPY-2 phase III results. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(suppl 5):S949-S1039. doi:10.1016/annonc/annonc729

33. Garon EB, Lu S, Goto Y, et al. LBA49 - CANOPY-A: Phase III study of canakinumab (CAN) as adjuvant therapy in patients (pts) with completely resected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol. 2022;33(suppl 7):S808-S869. doi:10.1016/annonc/annonc1089

34. Ehrhardt S, Appel LJ, Meinert CL. Trends in National Institutes of Health funding for clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. JAMA. 2015;314(23):2566-2567. doi:10.1001/ jama.2015.12206

35. Wages NA, Chiuzan C, Panageas KS. Design considerations for early-phase clinical trials of immune-oncology agents. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):81. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0389-8

36. Kola I, Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(8):711-715. doi:10.1038/nrd1470

37. Nakhoda SK, Olszanski AJ. Addressing recent failures in immuno-oncology trials to guide novel immunotherapeutic treatment strategies. ˆ. 2020;34(2):83-91. doi:10.1007/s40290-020-00326-z

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More