Roundtable Discussion: Stadtmauer Discusses Frontline Combination Treatments in Multiple Myeloma

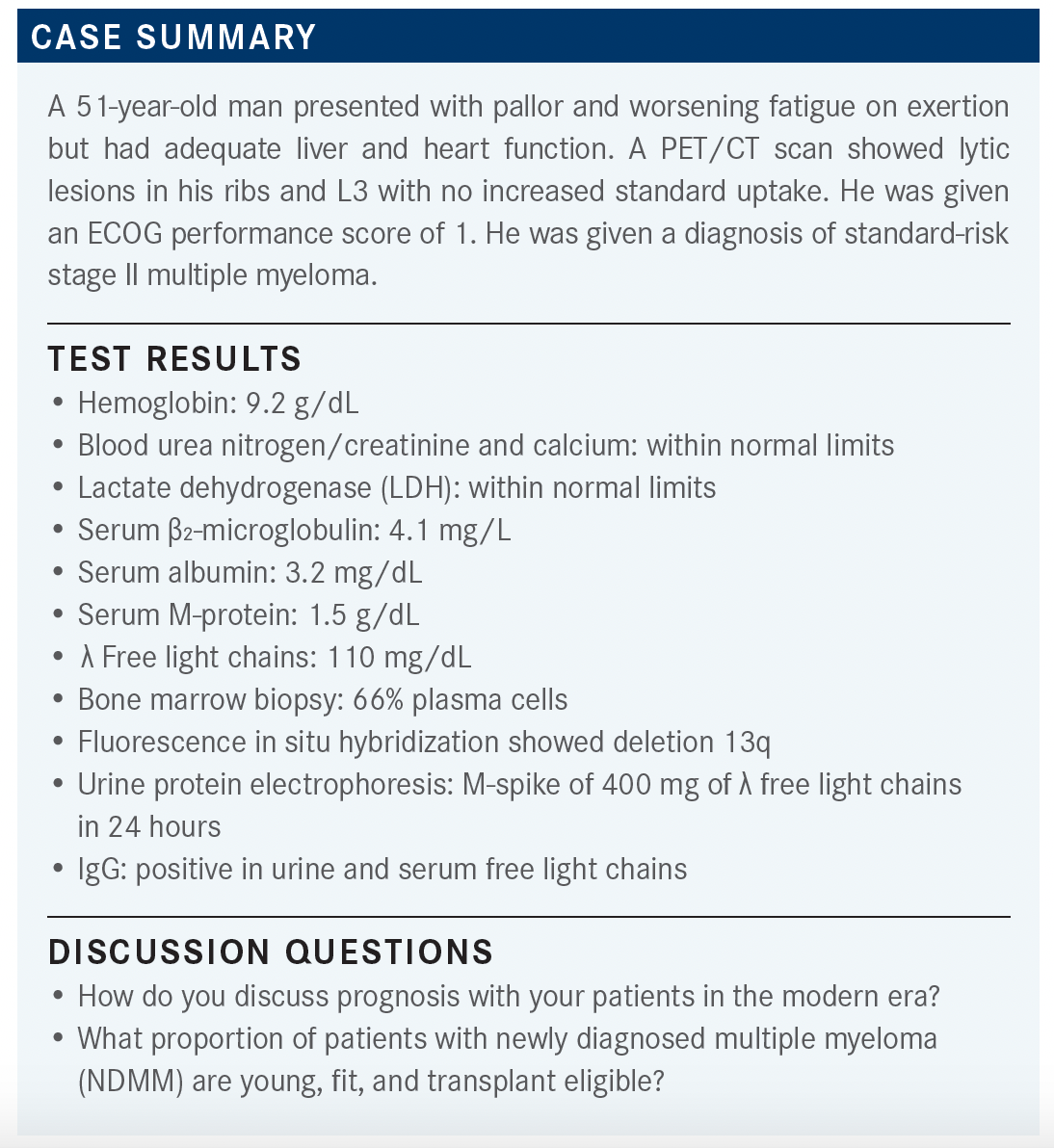

A 51-year-old man presented with pallor and worsening fatigue on exertion but had adequate liver and heart function.

Edward A. Stadtmauer, MD

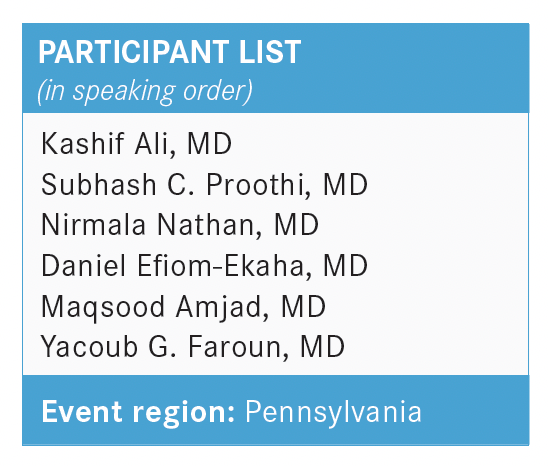

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable event, Edward A. Stadtmauer, MD, section chief, Hematologic Malignancies Roseman, Tarte, Harrow, and Shaffer Families’ President’s Distinguished professor, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, discussed the case of a 51-year-old patient with multiple myeloma.

ALI: I would tell the patient that things have changed a lot, and as we are having more and more modern treatments, people are living a lot longer than they used to. In fact, if you look at a lot of the newer data, people with standard-risk cytogenetics can possibly live up to 15 years [longer] if they’re put on appropriate treatments, go through transplant, respond well, and go on a lenalidomide [Revlimid] maintenance therapy.

A lot of us are now using minimal residual disease [MRD] to see if any of our patients are MRD negative, and it may not make a difference as far as the treatment regimen you pick, but it can tell you a little about a prognosis. [It’s] a little hard to tell up front how long someone is going to live, but I tell them that the treatments have gotten better and, even though myeloma is not a curable disease, our plan is to keep it at bay and keep it on some sort of maintenance. We try to keep it as deep in remission as we can [for] as long as possible.

STADTMAUER: That’s probably a good, generalized way that we’re all doing it—that we’re sort of optimistic. I usually tell them things like, “When I started, I was happy if 50% of the patients would respond to therapy, and people would live for several years. Now I expect 90% of patients to respond to therapy, and for people [to] live for potentially decades.”

The next question I tend to get is, “What stage am I?” I tend to tell them, “I don’t know. I don’t think of staging so much in this disease. I see it more like pregnancy—you’re either pregnant or you’re not—and you’re pregnant, so now we’re going to get you treated.”

What age do you think of as young nowadays?

PROOTHI: Seventy-five years old. You try to use triplets on everybody as much as you can, and [you] try to get transplantable people to transplant, so that’s what I look at.

STADTMAUER: Maybe the more important question is: Who would you not consider eligible for a transplant, and what characteristics are you primarily using for those decisions?

NATHAN: [If they have an] ECOG performance score of 3 or 4, I would not send them for transplant.

ALI: A lot of that depends on your transplanter, how they feel, and how comfortable they are with transplanting patients. I’m not that concerned about the ages of patients [as much] as I am about whether they’re transplant eligible or not. Also, there are going to be some patients [who] do not want transplant, which is fine. I mean, you discuss it with a patient [and] you tell them transplant is an option.

If they ask you, “Is it going to cure my disease?” and you say, “No, it’s not going to cure it, but you’ll get a deeper remission and you’ll [possibly] be off active treatment for longer,” maybe they’ll do it. It really depends on your transplant center, and there are transplant centers that are more comfortable transplanting older patients compared [with] others.

PROOTHI: It [mostly] depends on the organ functions of the person.

NATHAN: The performance status, too.

PROOTHI: Yeah, if they’ve got [a good] heart, good lungs, [a] good liver, or good kidneys.

STADTMAUER: What I’m hearing is age is not as important as physiologic age of organ functions and performance status. There is not a right or wrong here, and patients are a major aspect of the decision. The other thing I try hard to do is not [decide] in the early treatment or diagnosis of a patient about whether they would be a transplant candidate. That comes after they’ve gone into remission or had treatment because performance status can change, organ function can change, etc. Do any of you do the transplants in your own institution, or are you all referring patients to other institutions for the transplant?

ALI: We’re a private practice, so we refer ours out.

STADTMAUER: The message I give to [all] the patients is: The best care for a patient with myeloma is that collaboration between the excellent oncologists locally and an oncologist at a center that either does transplants or has an expertise in this particular area. It’s that collaboration that works best in this disease—and probably in most of the diseases we deal with—but particularly in myeloma.

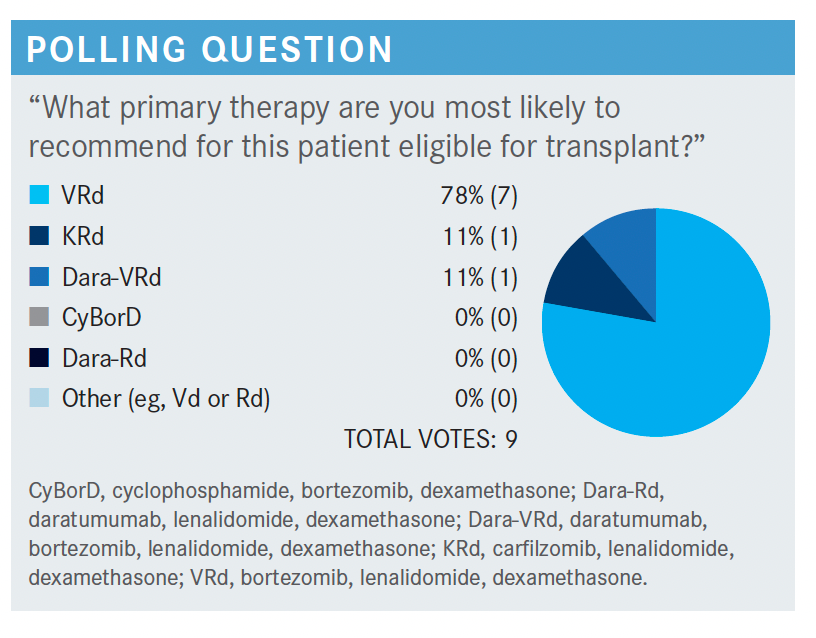

STADTMAUER: What’s your go-to regimen? How do you pick it for the young patient who you anticipate may go on to a transplant?

EFIOM-EKAHA: I typically would start with VRd [bortezomib (Velcade), lenalidomide, and dexamethasone] as a standard for my standard-risk patients [who] are going to transplant. [Sometimes] I do use KRd [carfilzomib (Kyprolis), lenalidomide, and dexamethasone] in patients with high-risk cytogenetics [who] are young, fit, [and] going for a transplant. I have not [yet] evolved to a quadruplet as my front line in patients [who] are going to transplant.

I’m waiting for a little more data and guidance, but standard therapy overall is still VRd for me.

PROOTHI: I use VRd because that’s what I’ve been using all these years. I don’t think KRd has improved any more than VRd, but I would like to use dara-VRd [daratumumab (Darzalex), bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone] because that will give a deeper and early depth of response—and the much higher MRD.

AMJAD: I use KRd in high-risk patients and in patients [who] have neuropathy and I’m afraid they’re going to worsen—especially if they’re diabetic patients—and when I’m not sure [whether] they will be able to go on [the] transplant route.

STADTMAUER: To try to get the deeper remission, as deep a remission as you can.

AMJAD: Based on the data that you used 12 cycles of KRd, you get [an] excellent, deep response.

ALI: You could make an argument for pretty much [all] these regimens. In my clinical practice, for standard-risk patients, I am still doing mostly VRd. For high-risk [patients], KRd, [and] there’s some data out there for dara-VRd as well.

If someone has multiple myeloma [and] amyloidosis along with that, then there is dara-CyBorD [daratumumab, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone]. There’s no 1 perfect regimen for everybody anymore. It used to be “We should do that,” but you can tailor these regimens for each patient type.

FAROUN: Regarding the risk factors, I use VRd initially for induction. If the patient did not respond, I [would] add daratumumab to this regimen, make it quadruple, and get a response with adding daratumumab. The idea is to get VGPR [very good partial response] and have the patient ready for transplant.

BACH: VRd is a very safe regimen we’ve adapted over the years. For high-risk patients, you think about something a little stronger—at least I do. It’s a good start—maybe [even] if you don’t know the FISH studies—but most of the time, we have those back.

The other question is: Would the higher risk/benefit from quadruplet therapy [be worth it]? I do refer [a lot of my patients] to see [whether] they’re transplant candidates, so VRd is a nice start [until someone else] weighs in and says, “This is what we would do.” Then it’s easy enough to switch gears at that point [and] add something [to the treatment].

STADTMAUER: We’re not emphasizing the cytogenetics and high-risk vs standard-risk patients, but that is more and more coming into at least the question of initial therapy and even consolidation therapy. Should we differentiate the high-risk patients from the standard-risk patients?

ALI: The other thing is, if you look at the newer trials, including with dara-RVd, they’re starting to look at MRD-negativity. If you look at isatuximab-irfc [Sarclisa] plus KRd, they also looked at MRD negativity in their second-line trials.

It’s good because now we’re going to see how much that makes a difference and [whether] we should be going for MRD negativity, [as] we know there’s some prognostic implications for those patients.

STADTMAUER: How about in terms of insurance? Would you say all these regimens are equally easy to initiate? Or have you had some pushback from some of these regimens?

ALI: I’ll tell you from the private practice standpoint. I’m on the [pharmacy and therapeutics] committee for our group, [and] we have not had any issues thus far. There is an issue with FDA approval, so some of these are not going to be FDA approved for first line, especially for transplant-eligible patients. But we’ve not had any issues [so far]. We did have to get dara for free for 1 patient, so we’ve [mostly] had no issues with starting the patient on whatever regimen we wanted to start thus far.

STADTMAUER: I’ve had 1 or 2 patients push back from the dara-VRd, where they’ve said, “You could do the dara-Vd or dara-Rd, but not dara-VRd.” Hopefully, that’s changing.

ALI: That’s the same problem we have with one of our patients, so we have to get the daratumumab for free for that patient.

FAROUN: What we have learned from the data [is] that if the patient achieved VGPR, regardless of the induction therapy, they’re a good candidate for a transplant, as well as later for disease-free survival. It’s my opinion to get the patient into VGPR and send them to transplant.

STADTMAUER: The most important thing is having a regimen that works. [Fortunately], most of these regimens are working. I would put in there that [it is important that the regimens] work and are [also] well tolerated. You can have the most active regimen in the world, but if [patients] have horrible neuropathy or have horrible diarrhea [with] their lenalidomide, then they’re not going to tolerate it, and you’re not going to get great results. So, you [must] be flexible in dosing [and] in schedule. You pick something, start it up, then make some adjustments relatively quickly.

EFIOM-EKAHA: I’m not doing MRD testing because I still don’t know what to do with it. It’s a very good tool as a clinical trial strategy, but I’m not doing it in clinical practice because I honestly don’t know what to do with it.

STADTMAUER: Is that a consensus?

ALI: I have started doing MRD-negative testing. You can call clonoSEQ, which is the lab that does it, [and] they’ll get you registered, [then] you can become one of the providers. So I’ve started doing it just so a patient can plan the rest of their life. I understand it doesn’t change what we’re doing as far as treatment, but [from a patient standpoint], wouldn’t it be nice to know what the chances [are] going forward? There was a benefit to being MRD negative whether you got the transplant or not, so I do it just to know how the patient is going to do in the long run. The patients want answers, too. I don’t want to hide information I could potentially have, even though it may not make a difference as far as my treatment.

FAROUN: The question is: If you have a patient with MRD-positive disease, what do [you do], and how often [do] you do MRD thereafter? Is it 1 time only, or [do] you do it every 2 or 3 months, and do you act upon it?

ALI: I have not been doing it long enough to be able to repeat MRD yet. Honestly, I just started doing it in the past 2 months, and that’s the question I have in my head.

The question is: If they’re MRD negative, do you repeat it 3 months later? Which is a great point you brought up. I would do it if I see any other changes or if I have a situation where the patient may not be tolerating their regimen, and the MRD negativity may be something that may be able to push them either way. So I don’t have a clear answer to that question. It’s going to be patient-specific, and we’ll see what the data show.

EFIOM-EKAHA: My other concern is, if I do it and I have an MRD-positive [patient], I’m not sure what time point I [would] do it. [If] the patient was going to go to a transplant, I’ll confirm with my transplanter. But does that mean [that I should just] switch my regimen? I don’t know, maybe we’ll come to a time where that would be well advised, that maybe you need to change before you go to the transplant, but I honestly don’t know that yet. I’m also worried about the positive MRDs. I don’t know how they fit into treatment.

ALI: I don’t think you should because [the data show] transplant always did better than no transplant. We’re going to have to do better with our regimen. I mean, look at the dara-RVd trial.1,2 There was a higher MRD negativity rate, and a lot of us are using high-risk cytogenetics as a reason to put people on dara-RVd, but standard-risk [patients] did even better. Maybe we need to do it for everybody, because if we get more people MRD-negativity, then they go for transplant, you don’t want to keep frying your patient with all these regimens just because they’re not MRD-negative with your first test.

STADTMAUER: Every study needs to have MRD as part of [it], but I’m not yet making tremendous clinical decisions on the patients who are not on study, based on that testing. Although I do have some patients who will ask me, “After 2 or 3 years of maintenance therapy, can I stop this? I’m in a nice remission.”

That is the subject of our current big, randomized trial of lenalidomide vs dara-lenalidomide as a maintenance therapy—that it’s going to use MRD testing after 2 years. If the MRD test is negative, then half the patients will continue their maintenance and half won’t, and that will give us important information. But for the patient who would like to stop the therapy, particularly if they’re having toxicity, I sometimes offer them an MRD test. If it’s negative, I’ll feel more comfortable doing that.

ALI: I’m still using more bortezomib compared [with] carfilzomib. You can weed out a certain population that may have benefited from VRd, but KRd also has different toxicities. So we’re talking a lot about the cardiac toxicities, which are not there with VRd, but then VRd has issues with neuropathy, which is a bit of a challenge in some patients. So I’m still doing more VRd, but there are going to be some patients who will benefit from KRd, especially like Dr Amjad talked about earlier, about the high-risk patients.

STADTMAUER: You can conclude from the [ENDURANCE] study [NCT01863550] that when you have a result that is no different, that means that you can use either. There’s not a right or a wrong there. It’s a different toxicity profile, so we don’t have a preferred proteasome inhibitor for probably either option.

STADTMAUER: Do you anticipate that 4-drug regimens, meaning that CD38 monoclonal antibody, VRd, or KRd is going to become the standard, or do you think we’re going to continue with the triple regimen?

FAROUN: It’s a phase 2 study.1,2 The question is: Are they going for phase 3 study or not? We are using RVd induction therapy on phase 1 or 2 study on the patient, and we adopted that physically [and] nationally, so I’m not sure. It depends on the FDA approval. If it’s FDA approved on phase 2 study, we can adopt that quadruple therapy.

EFIOM-EKAHA: It is certainly a very expensive regimen, though. Dara-RVd is not going to be approved, and it doesn’t exclude patients from transplants. So just imagine dara-RVd transplant and dara-R maintenance— that’s very, very expensive. I’m not sure I can clearly state what we’re getting in benefit, in terms of standard RVd transplants and R maintenance. I guess we need larger studies and more data, but I’m worried we’re going to be dealing with extravagant costs without necessarily proving significant benefit.

ALI: My feeling is that this is going to be the standard of care. I’m thinking the anti-CD38s are going to be like a rituximab [Rituxan], just how you do R-CHOP [rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine (Oncovin), and prednisone], then you go to RICE [rituximab, ifosfamide (Ifex), carboplatin, etoposide]—a similar sort of thing. You can do dara-RVd, then when they progress, you can go to isatuximab-KRd. I think we’re going to see a lot more daratumumab or isatuximab in a lot of our regimens. I haven’t gone through the clinical trials and seen how these patients are doing in the long run. I have a lot of patients on daratumumab maintenance, and they’re doing great.

References:

1. Voorhees PM, Kaufman JL, Laubach J, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: the GRIFFIN trial. Blood. 2020;136(8):936-945. doi:10.1182/ blood.2020005288

2. Kaufman JL, Laubach JP, Sborov D, et al. Daratumumab (DARA) plus lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVd) in patients with transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM): updated analysis of Griffin after 12 months of maintenance therapy. Blood. 2020;136(suppl 1):45-46. doi:10.1182/ blood-2020-137109

Gasparetto Explains Rationale for Quadruplet Front Line in Transplant-Ineligible Myeloma

February 22nd 2025In a Community Case Forum in partnership with the North Carolina Oncology Association, Cristina Gasparetto, MD, discussed the CEPHEUS, IMROZ, and BENEFIT trials of treatment for transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.

Read More