Porter Explores Data for Sotorasib in KRAS-Mutated NSCLC

During a Targeted Oncology™ Community Case Forum event in collaboration with the Tennessee Oncology Practice Society, Jason Porter, MD, reviewed the CodeBreaK 100 and CodeBreaK 200 trials of sotorasib for patients with KRAS-mutant non–small cell lung cancer.

Jason Porter, MD

Director, Lung Cancer Disease Research Group

West Cancer Center and Research Institute

Memphis, TN

CASE SUMMARY

- A 68-year-old woman presented with dyspnea on exertion, fatigue, and anorexia.

- She had medically controlled diabetes mellitus and took an OTC gastric acid reducing agent as needed.

- A former smoker, she quit 10 years prior (20 pack-years).

- On physical examination, she was thin-appearing.

- Laboratory results were within normal limits.

- Imaging:

- Chest x-ray showed 2 left lower lobe masses.

- Chest/abdomen/pelvic CT scan confirmed 2 masses (3.5 cm and 5.2 cm) in left lower lobe of lung and multiple liver lesions.

- PET scan showed activity in the left lower lobe and liver masses.

- Brain MRI: negative

- Bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy of the left lower lobe confirmed lung adenocarcinoma; PD-L1 20%

- Staging: IVA adenocarcinoma; ECOG performance status of 1

- Tumor next-generation sequencing: KRAS G12C-positive, negative for other alterations

- PD-L1 expression: 20% by immunohistochemistry

- She received carboplatin and pemetrexed (Alimta) plus pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and achieved a partial response at completion of 4 cycles of chemotherapy; pemetrexed plus pembrolizumab maintenance continued.

- Sixteen months later, the patient reported worsening back pain and shortness of breath.

- CT scan showed progression in lung tumors and liver metastases and a new adrenal metastasis.

- Repeat MRI of the brain showed a single metastatic site.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: How should a patient with KRAS G12C-mutated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) be treated?

The first-line therapy for patients with adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma is what’s already FDA approved such as those used in KEYNOTE-189 [NCT02578680], KEYNOTE-407 [NCT02775435], and IMpower150 [NCT02366143]…and for some patients, the quadruplet regimen from CheckMate 9LA [NCT03215706] or CheckMate 227 [NCT02477826].1 But then at the time of progression, at response evaluation, these patients should go to sotorasib [Lumakras] or adagrasib [Krazati] by NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] recommendation. If they are responding [to frontline therapy] at your assessment, keep going for more cycles, then rescan. If they progress, go to the KRAS inhibitor therapy, and if they’re stable, keep going with your maintenance until progression, but at progression, use KRAS-specific therapy, and then beyond that, probably a clinical trial if you have one available. Remember that palliative care and hospice…are not inappropriate for some of these patients, depending on their quality of life and their own decisions and input.

What trial led to the accelerated approval of sotorasib for KRAS G12C-mutated NSCLC?

This was the phase 2 CodeBreaK 100 study [NCT03600883]. This study design looked at sotorasib at 960 mg once a day, orally. The patients were eligible if they had locally advanced or metastatic KRAS G12C-positive NSCLC that had progressed on prior therapy. Similar to what we saw in the KRYSTAL-1 trial [NCT03785249] of adagrasib, they could have stable brain metastases. The difference is that no more than 3 lines of therapy were allowed, whereas in that other trial the patients could have more than 3 lines of therapy.2,3 Treatment beyond progression was allowed, and safety follow-up occurred at 30 days plus/minus 7 days after the last dose of sotorasib and long-term follow-up every 12 weeks for up to 3 years.

[They were] mostly smokers, also mostly White.2 There’s 1 difference between [this trial] and KRYSTAL-1, [which is] that KRYSTAL-1 had about 6% or 7% patients who were African American.3 This trial has 1.6%, and obviously we can’t forget about that now, because it’s a big part of…trying to get diverse patient populations on clinical trials, because we see a difference in EGFR.2

What are we going to see in KRAS [inhibition] if we look at patients who are African American? Do they respond at the same rate? Do we want to even put them on the therapy? It’s important that we get to study this and sometimes we just have to do it in the real world. We can get all of our patients together and look to see what their responses to KRAS inhibitor therapy look like if they weren’t in the population here.

About 70% had ECOG performance status of 1. Most had adenocarcinoma, just like the KRYSTAL-1 trial, and about 97% of them had metastatic disease. About 90% had platinum-based chemotherapy, [and] 81% of them had chemotherapy plus immune checkpoint inhibitor. The objective response rate [ORR] in the initial analysis was 37.1%, with a disease control rate [DCR] of 80.6%.2 [Although] this is not overall survival [OS]…if I have [a high] DCR on second-line therapy, maybe they don’t have to die paralyzed or with new brain metastases that they didn’t have before.

DCR is a very important end point. OS as a primary end point in these [trials] is hard to do…. The median duration of response [DOR] was 11.1 months, median progression-free survival [PFS] looked very similar to the KRYSTAL-1 trial at 6.8 months, and median OS was 12.5 months.

What was the safety profile of sotorasib observed in CodeBreaK 100?

The adverse events [AEs] included those gastrointestinal AEs that we see [with adagrasib] as well as 12% hepatic toxicity of grade 3/4.4 Obviously, we’re checking these at baseline. Musculoskeletal pain is present at 35% any grade. [However], is it from the therapy or is that from prior immune checkpoint inhibitor?

Making sure that any AE that they have on this therapy is not an immune checkpoint inhibitor–related AE is very important…especially in a community where your pulmonologist is not as easily accessible. You don’t want to assume that a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation is pneumonitis or interstitial lung disease and take them off therapy. It’s important to keep all hands on deck for these patients with lung cancer. Then we see metabolic changes, pneumonia, and rash [each] in 12% of the patients.

What was observed in later follow-up of this trial?

That was the initial analysis at 1 year. But looking at 2 years, we went from 37.1% to 41% of the patients with a response at 2 years.5 The partial response rate was 38% and complete response, different from KRYSTAL-1, is now 3%. It doesn’t seem like a lot, but 1% vs 3%, there’s a difference.2,5

We start to look for little subtle things that we can use to differentiate these [therapies] because that’s going to be more challenging to do. There was stable disease in 43% of those patients, for a DCR of nearly 85% and a median DOR of 12.3 months, with 73% of them responding for at least 6 months.5 The Kaplan-Meier curves mirror the data [from KRYSTAL-1].2,5

What did the biomarker analysis of this trial show?

CodeBreaK 100’s biomarker analysis is [interesting]. I was trying to figure out why our PD-L1–negative patients look like they’re doing so well with a PFS rate [of at least 12 months of 52%] compared with more patients who had early progression, with a PD-L1 of 1% to 49% or at least 50%.5 It seems like more of them are having early progression; I don’t know how to interpret that other than to say maybe those patients who are PD-L1 negative definitely got chemotherapy, whereas these patients with PD-L1 expression may or may not have gotten chemotherapy.

Other relevant mutations were KEAP1 and [secondary] RAS, and some of those patients showed early progression. ROS1 [did so as well, but] we expected that. KEAP1 we know is [associated with] immune resistance. I don’t know how to interpret that. But patients with RET, PDGFR, and EPH seem like they’re having more long-term [PFS] benefit greater than or equal to 12 months.

Median OS was 14.9 months for those with 1 prior line of therapy, 11.5 months with 2 prior lines, and then 11.7 months for 3 prior lines. If you can get them onto [sotorasib] in the second line, it’s looking better. If they haven’t had prior PD-L1 therapy, median OS [is 24.0 months].

The number of those patients is 17 vs 155 patients who had prior PD-L1 therapy, but there are some thought-provoking results with that 24-month median OS. Is it going to behave like EGFR, where there’s a big difference in first- vs second-line therapy for those patients? I often wonder if KRAS inhibition will come to frontline as a single modality, considering that we have so many other comutations present for those patients.

What did the phase 3 CodeBreaK 200 trial (NCT04303780) show in terms of efficacy of sotorasib compared with docetaxel?

From the phase 3 CodeBreaK 200 trial, like we [have] with the KRYSTAL-12 trial [NCT04685135], we have sotorasib vs docetaxel, randomized 1:1 with 345 patients.6 The primary end point was PFS by blinded independent central review….

The primary PFS end point had a HR of 0.66 [favoring sotorasib; 95% CI, 0.51-0.87; P = .0017]. It was statistically significant with the median PFS at 5.6 months for sotorasib vs 4.5 months with the docetaxel. For the OS, which was the key secondary outcome, the HR is 1.01 [95% CI, 0.77-1.33; P = .53]. The question is, is OS the only important outcome?

We saw 10.6 months median OS with sotorasib vs 11.3 months with docetaxel in this patient population. But the...patients didn’t have to come in for intravenous infusions; they were on an oral therapy, and they were able to stay home.

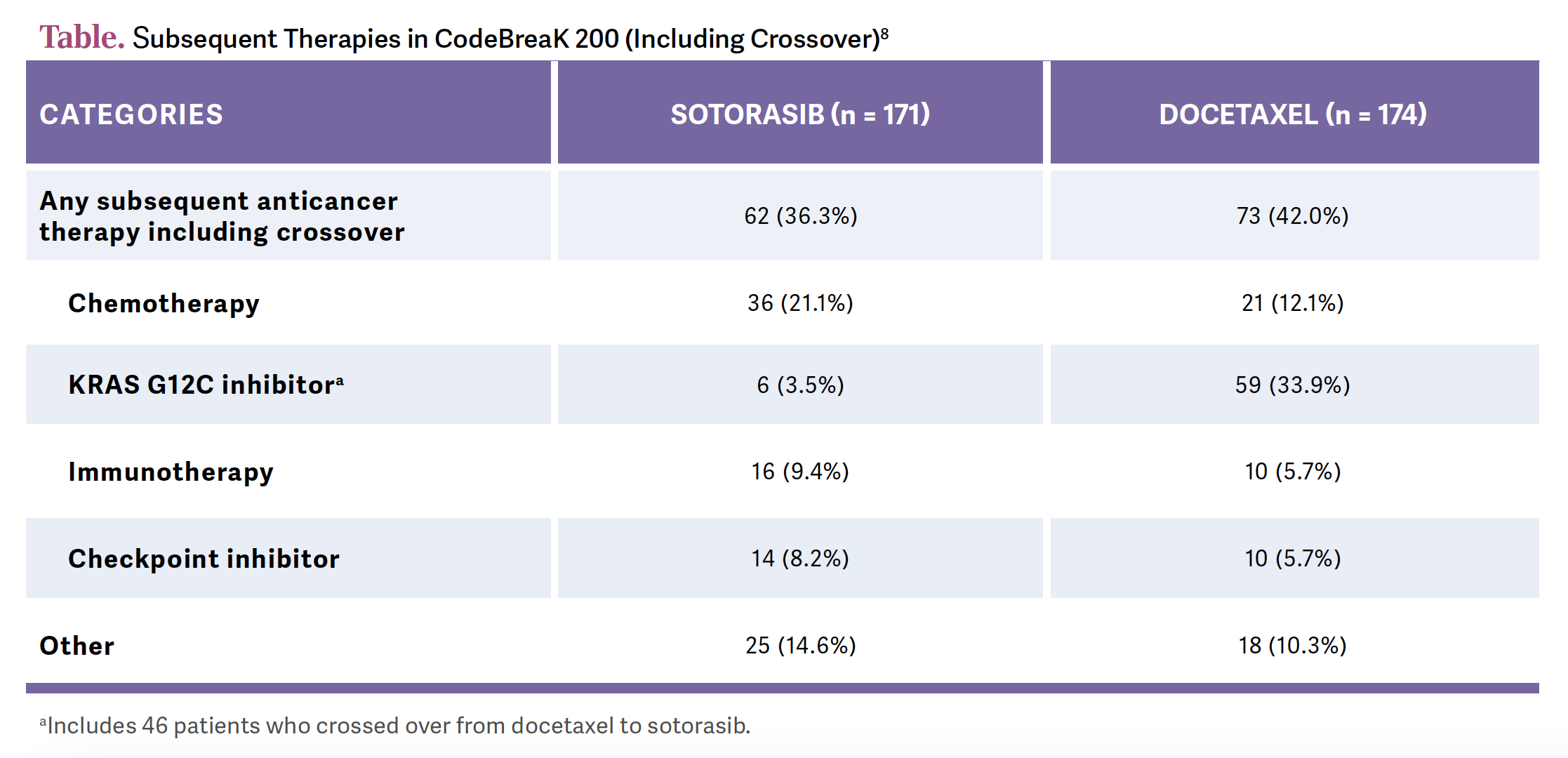

They didn’t get COVID-19 exposure and a whole lot of other things that can happen. What I take from this was that it was not inferior, and it’s a chance if your patient can’t come in anymore. There was also a lot of crossover [from the docetaxel arm to sotorasib]. What’s considered a line of therapy is also heterogeneous because I may treat somebody with chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and then come back and add a chemotherapy later. Is that 1 or 2 lines of therapy? How am I counting that? How is the next physician going to count it? We have a lot going on there, but it is clearly not inferior here. [In terms of] the crossover, 6 patients [3.5%] in the sotorasib arm [received subsequent] KRAS G12C inhibitor vs 59 [33.9%] of the patients on the docetaxel arm [Table8].

The ORR was 28.1% with sotorasib vs 13.2% with docetaxel, and the DCR was 82.5% vs 60.3%, [respectively]. The median DOR was 8.6 months for sotorasib vs 6.8 months for docetaxel. We can see from the prior lines of therapy that using docetaxel after sotorasib if they progress is the way, and it’s very important to look for clinical trials for those patients. If they’re able, get a repeat biopsy so that we can help to elucidate more of those mechanisms of resistance.

Looking at the biomarker analysis, we have [alterations including] SDK11, KEAP1, and EGFR, and the biomarkers don’t seem to make a difference, which tend toward sotorasib, but even with some of these other [alterations], RET, ROS1, and HER2, all of those have their own therapies anyway, so even though they were included in the trial, we would be treating with those appropriate therapies now, but some of those were not approved at the time of this clinical trial.7

Intracranial efficacy is looking good [20.0% intracranial complete response with sotorasib vs 6.9% with docetaxel].8 In these patients, liver, adrenal, bone, and brain metastases are where these diseases go. If we can protect the central nervous system, it’s very important.

REFERENCES:

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 3.2023. Accessed September 26, 2023. https://tinyurl.com/ydsfxfaz

2. Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2371-2381. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103695

3. Jänne PA, Riely GJ, Gadgeel SM, et al. Adagrasib in non-small-cell lung cancer harboring a KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(2):120-131. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2204619

4. Lumakras. Prescribing information. Amgen; 2021. Accessed September 26, 2023. https://tinyurl.com/mr266wu4

5. Dy GK, Govindan R, Velcheti V, et al. Long-term outcomes and molecular correlates of sotorasib efficacy in patients with pretreated KRAS G12C-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer: 2-year analysis of CodeBreaK 100. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(18):3311-3317. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.02524

6. de Langen AJ, Johnson ML, Mazieres J, et al. Sotorasib versus docetaxel for previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer with KRASG12C mutation: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10378):733-746. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00221-0

7. Skoulidis F, De Langen A, Paz-Ares LG, et al. Biomarker subgroup analyses of CodeBreaK 200, a phase 3 trial of sotorasib versus (vs) docetaxel in patients (pts) with pretreated KRAS G12C-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16):9008. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.9008

8. Dingemans AMC, Syrigos K, Livi L, et al. Intracranial efficacy of sotorasib versus docetaxel in pretreated KRAS G12C-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): practice-informing data from a global, phase 3, randomized, controlled trial (RCT). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 17):LBA9016. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.17_suppl.LBA9016

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More