Mitigating Toxicities Arising From Combination Therapies in RCC

Combination therapy with checkpoint blockade, also termed immuno oncology agents, and multikinase tyrosine kinase inhibitors are rapidly becoming the first-line therapy of choice in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

About 3 months ago 3, I examined an older gentle man in my clinic who was receiving cabozantinib (Cabometyx) and nivolumab (Opdivo) for metastatic kidney cancer. Routine blood work showed a 10-fold increase in his alanine aminotransferase levels. He had not started any new medications recently, had not been ill, and did not consume alcohol. Recent imaging had not shown any cancer in his liver. Hepatitis serology was negative. It was evident that his abnormal liver function was related to his cancer therapy, and the patient asked me how we should proceed.

The real question in this case is related to identifying which of the 2 drugs was primarily responsible for liver toxicity. For those of us who manage advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC), this is not an unusual problem. Combination therapy with checkpoint blockade, also termed immuno oncology (IO) agents, and multikinase tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are rapidly becoming the first-line therapy of choice in patients with metastatic clear cell RCC. There are currently no less than 4 FDA-approved combination regimens available in this space.

Despite subtle differences in the mech anism of action, these combinations share many similarities, and all have demonstrated dramatic improvement in progressionfree survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Not surprisingly, such efficacy has led to a rapid acceptance of these regimens by the community of medical oncologists. As a result, evergreater numbers of patients are now at risk of developing such toxicities, so it is imperative to gain familiarity with both the diagnosis and management of these toxicities.

Trials Leading to FDA Approvals

To understand the rise of these combinations, it is helpful to summarize the landmark trials that led to their approval. The first combi nation of this kind to receive FDA approval was axitinib (Inlyta), an inhibitor of VEGF receptors 1, 2, and 3, with pembrolizumab (Keytruda), a humanized IgG4 antibody targeting PD-1 receptors on activated T cells. Approval was granted in April 20191 based on the KEYNOTE-426 trial (NCT02853331) that demonstrated an objective response rate (ORR) of 59.3% and a complete response (CR) rate of 5.8%.2 On extended followup, the median PFS was noted to be 15.7 months, with a median OS of 45.7 months.3

Following on the heels of the axitinibpembrolizumab approval, the combination of axitinib with avelumab (Bavencio), a fully human IgG1 antibody directed against PD-L1 on tumor cells, was approved in May 20194 based on the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial (NCT02684006),5 which showed an ORR of 51.4% and a CR rate of 3.4%. On extended follow-up, the median PFS was 13.3 months, and the median OS was still immature.6

Approval for the third combination came in January 20217 when the CheckMate 9ER trial (NCT03141177)8 using cabozantinib—a multikinase TKI targeting VEGF receptors, AXL, MET, RET, and ROS1, among others—with nivolumab, a fully human IgG4 antibody against PD-1, showed ORRs of 55.7%, with CR rates of 8%. These findings were confirmed on extended follow-up, demonstrating a median PFS of 16.6 months and a median OS of 37.7 months.9

Finally, the duo of pembrolizumab and lenvatinib (Lenvima), a multikinase TKI targeting VEGF receptors, FGF receptors, PDGFRA, and RET, among others, was approved in August 202110 based on findings from the CLEAR trial (NCT02811861),11 which delivered the best performance yet of any combination regimen. This trial demonstrated an overall response rate of 71% with a CR rate of 16%. The median PFS was 23.9 months, and the median OS has not yet been reached.11

Importantly, all 4 IO-TKI combinations showed activity across all International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium risk groups, blurring the distinction between these groups for treatment decisions. The CR rates were even more striking, especially in comparison with the relatively low rate of CR with IO or TKI monotherapy.

The reasons behind such synergism between IO and antiangiogenic TKIs are still not fully understood. Putative mechanisms include disruption of the direct suppressive effects of VEGF on immune cells and blockade of VEGF-mediated upregulation of PD-L1 expression on dendritic cells, leading to a reversal of T-cell exhaustion and ultimately boosting response to IO therapy. Proangiogenic molecules also alter the microvasculature around the tumor, leading to impaired infiltration of the tumor by immune cells and driving tissue hypoxia, which induces immunosuppression by recruiting regulatory T cells and tumor-associated macrophages to the tumor microenvironment. VEGF-directed TKIs can reverse these processes, allowing greater penetration of cytotoxic T cells into the tumor microenvironment.12

Likelihood of Adverse Events

The flip side of combination therapy is a greater likelihood of developing adverse effects (AEs), a phenomenon that was consistently seen across all the seminal trials discussed above. Interestingly, although combining these agents leads to increased frequency and severity of toxicity, no emergent safety signals were noted.

In addition to the synergism between antiangiogenic therapy and IO leading to amplified “off target” autoimmune AEs, there is a direct overlap of toxicity between these drug classes, most notably in the skin, the gastrointestinal tract, the liver, and the thyroid. Of these toxicities, hypothyroidism is usually the easiest to manage with the institution of replacement therapy; dose modifications or treatment interruptions are not needed. The other 3 classes of toxicity frequently require dose modification and even treatment interruption depending on the grade of severity.

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of managing such toxicity is determining which agent within the combination is responsible. Strategies to manage IO-related AEs center around the use of steroid therapy and other immunosuppressive medications that have little role in TKI-related toxicities. Conversely, TKI-related toxicities are typically managed by dose reductions alone.13 The relatively recent introduction of these regimens has meant that there is little guidance from national guidelines on optimal management, so practitioners are often left to determine how best to tackle such situations on their own.

An important distinction between TKI- and IO-related toxicity lies within the mechanisms by which these AEs arise. TKI-related toxicity is largely mediated by the off-target effects of the drug itself. These AEs are often dose dependent and promptly reverse upon stopping the offending agent. Conversely, IO toxicity is usually mediated through the immune system and not by the direct effects of the drug, resulting in prolonged toxicity after cessation of therapy. Indeed, depending on the grade of severity, IO toxicity will often require initiation of systemic immunosuppressive therapy with steroids and other agents for direct reversal of autoimmunity, with prolonged tapers to prevent relapse of toxicity. This distinction is also related to the relatively short halflives of TKIs versus the prolonged half-life of IO agents. However, it should be noted that half-lives can vary significantly across individual TKIs and the specific half-life of the agent used must be considered when assessing toxicity. Withholding both drugs with staged reintroduction while monitoring for recurrence of toxicity is therefore a useful strategy when it is unclear which agent is responsible.14

Evaluating Toxicities

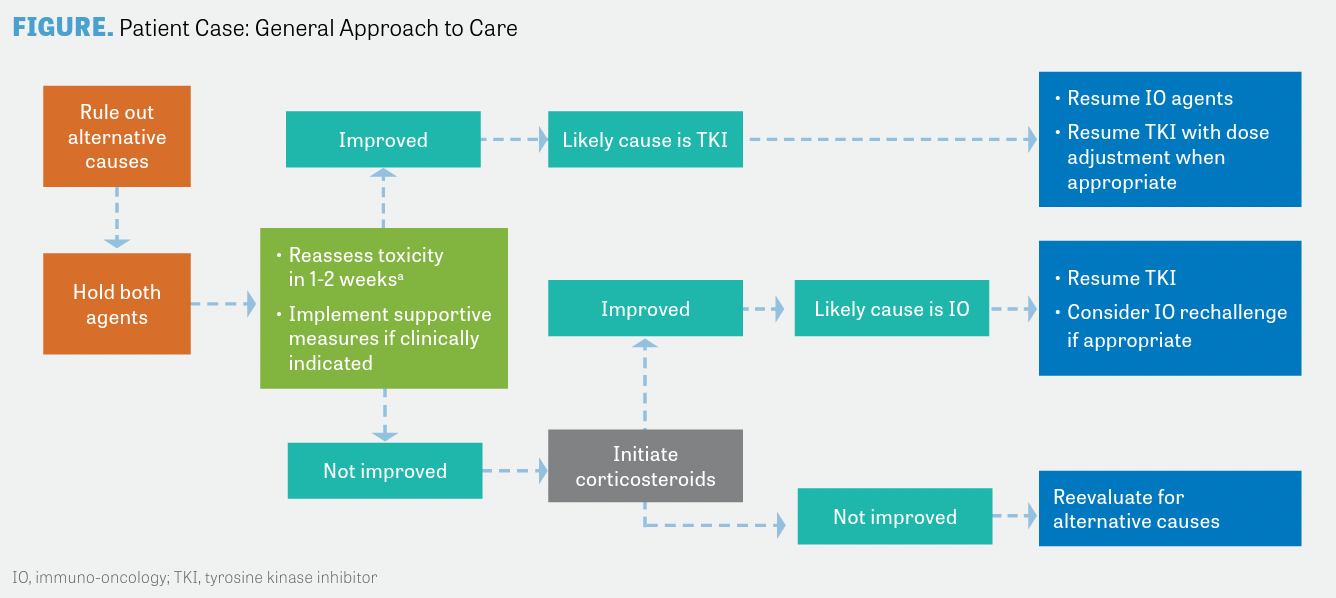

The process of evaluation is essentially a 3-step process (FIGURE). First, one must rule out other causes such as intercurrent infections, other medications, and direct involvement of the affected organ by the tumor in patients with liver dysfunction. Next, both drugs should be stopped. Finally, the toxicity must be reassessed after a certain period of time, depending on the half-life of the TKI used. If there is no improvement, consider initiating steroid therapy for presumptive IO-related AEs, depending on the grade of severity.

A few caveats must be considered when using this approach. Certain TKI-related AEs are predictable and have characteristic clinical features. In the case of skin toxicity, for instance, these drugs frequently produce palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, a syndrome that can be readily recognized by the experienced practitioner. In such cases, it is reasonable to stop the TKI alone and then reassess. On the other hand, in patients with severe toxicity, it is reasonable to start steroid therapy immediately because of the risk of rapid decompensation and death.

Returning to our patient, a decision was made to hold both cabozantinib and nivolumab and closely monitor liver function. On follow-up, his liver enzymes were noted to improve within a week and eventually returned to normal over a period of 4 weeks without further intervention. Nivolumab was then resumed, followed by cabozantinib, which was reintroduced 4 weeks later at a reduced dosage. The patient continued to feel well, and his liver function tests remained normal on follow-up. The liver toxicity was attributed to cabozantinib.

REFERENCES

1. FDA approves pembrolizumab plus axitinib for advanced renal cell carcinoma. FDA. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2023. http://bit.ly/3YKapSl

2. Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al; KEYNOTE-426 Investigators. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(12):1116-1127. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1816714

3. Rini BI, Plimack E, Stus V, et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro) plus axitinib (axi) versus sunitinib as first-line therapy for advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC): results from 42-month follow-up of KEYNOTE-426. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):4500. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.4500

4. FDA approves avelumab plus axitinib for renal cell carcinoma. FDA. Updated May 15, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2023. http://bit.ly/3IeTYYD

5. Motzer RJ, Penkov K, Haanen J, et al. Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(12):1103-1115. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1816047

6. Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ, Rini BI, et al. Updated efficacy results from the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial: first-line avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(8):1030-1039. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.010

7. FDA approves nivolumab plus cabozantinib for advanced renal cell carcinoma. FDA. Updated January 22, 2021. Accessed February 10, 2023. http://bit.ly/3IfeI2w

8. Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al; CheckMate 9ER Investigators. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):829-841. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2026982

9. Motzer RJ, Powles T, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma (CheckMate 9ER): long-term follow-up results from an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(7):888-898. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00290-X

10. FDA approves lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for advanced renal cell carcinoma. FDA. Updated August 11, 2021. http://bit.ly/3YnwaY8

11. Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha SY, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(14):1289-1300. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa2035716.

12. Rassy E, Flippot R, Albiges L. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immunotherapy combinations in renal cell carcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:1758835920907504. doi:10.1177/1758835920907504

13. Gao L, Yang X, Yi C, Zhu H. Adverse events of concurrent immune checkpoint inhibitors and antiangiogenic agents: a systematic review. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1173. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01173

14. Leucht K, Ali N, Foller S, Grimm MO. Management of immune-related adverse events from immune-checkpoint inhibitors in advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(18):4369. doi:10.3390/cancers14184369

Enhancing Precision in Immunotherapy: CD8 PET-Avidity in RCC

March 1st 2024In this episode of Emerging Experts, Peter Zang, MD, highlights research on baseline CD8 lymph node avidity with 89-Zr-crefmirlimab for the treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and response to immunotherapy.

Listen

Beyond the First-Line: Economides on Advancing Therapies in RCC

February 1st 2024In our 4th episode of Emerging Experts, Minas P. Economides, MD, unveils the challenges and opportunities for renal cell carcinoma treatment, focusing on the lack of therapies available in the second-line setting.

Listen