Immune Checkpoints to Watch: LAG-3

Immune checkpoint inhibitors an induce resistance through activation of additional immune checkpoints such as LAG-3. Research around LAG3 will be important for the future.

Jason Luke, MD

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target CTLA-4, PD-1, and PD-L1 have become a cornerstone of cancer therapy. 1 However, metastatic disease ultimately progresses in approximately half of all patients treated with ICIs, indicating a need for additional approaches.2,3

ICIs can induce resistance through activation of additional immune checkpoints such as LAG-3.4 LAG-3 is a surface receptor expressed on activated T cells. When activated, LAG-3 has immunosuppressive activity.5 Furthermore, LAG-3–expressing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes have been reported in multiple tumor types.5

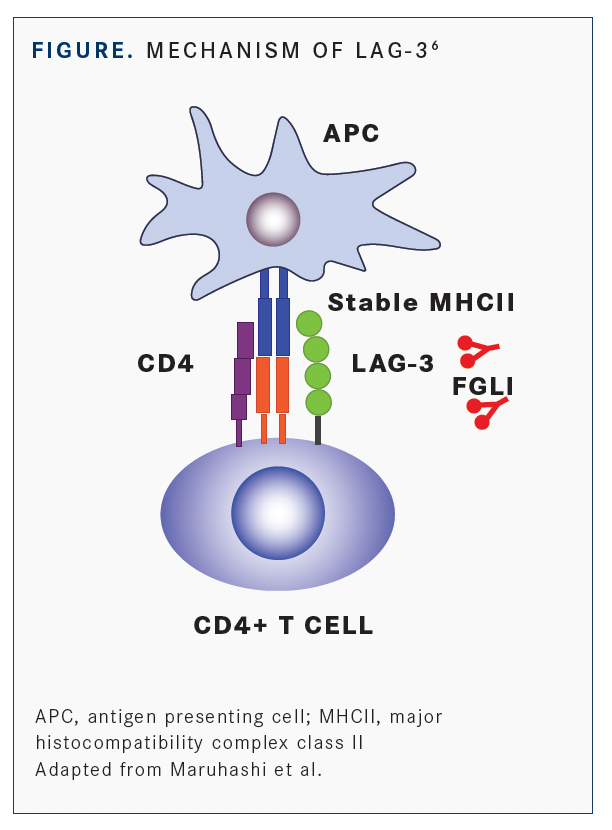

According to Jason Luke, MD, an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Hematology/ Oncology and the director of the Cancer Immunotherapeutics Center at University of Pittsburgh Hillman Cancer Center in Pennsylvania, LAG-3 is expressed in the context of T-cell dysfunction or putative exhaustion similar to PD-1. Whereas the PD-1 receptor has 2 ligands (PD-L1/L2), LAG-3 is known to have several binding partners of which major histocompatibility complex class II molecules and fibrinogen-like protein 1 (FGL1) are 2 of the best known (FIGURE6).

Luke told Targeted Therapies in Oncology™ that it is “not well understood which receptor-ligand is most important to interrupt” and this may have therapeutic implications for subsequent LAG-3 blocking approaches developed as anticancer agents.

Multiple clinical trials are under way to evaluate LAG-3–directed agents in combination with anti–PD-1 and/or anti–CTLA-4 therapy. Results of several of these trials were reported at the recent American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) 2021 annual meetings.

Relatlimab Plus Nivolumab Phase 2/3 Trial At ASCO, the primary phase 3 results of the RELATIVITY-047 trial (NCT03470922) were presented by Evan J. Lipson, MD, associate professor of oncology, with the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, and colleagues. The study evaluated the human IgG4 LAG-3-blocking antibody, relatlimab, in combination with nivolumab (Opdivo) compared with the standard of care anti-PD-1 monotherapy, nivolumab alone, in the first-line treatment of metastatic melanoma.7

According to Lipson, “relatlimab in combination with nivolumab modulates potentially synergistic immune checkpoint pathways and can enhance antitumor immune responses.”

In the RELATIVITY-047 trial, 714 patients were randomized 1:1 to receive a fixed-dose combination of relatlimab (160 mg) plus nivolumab (480 mg) given intravenously every 4 weeks or the same dose of nivolumab alone.

Over a median follow-up of 13.2 months, median progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly longer with the combination: 10.1 months (95% CI, 6.4-15.7) vs 4.6 months (95% CI, 3.4-5.6), resulting in an HR of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.6-0.9; P = .0055).

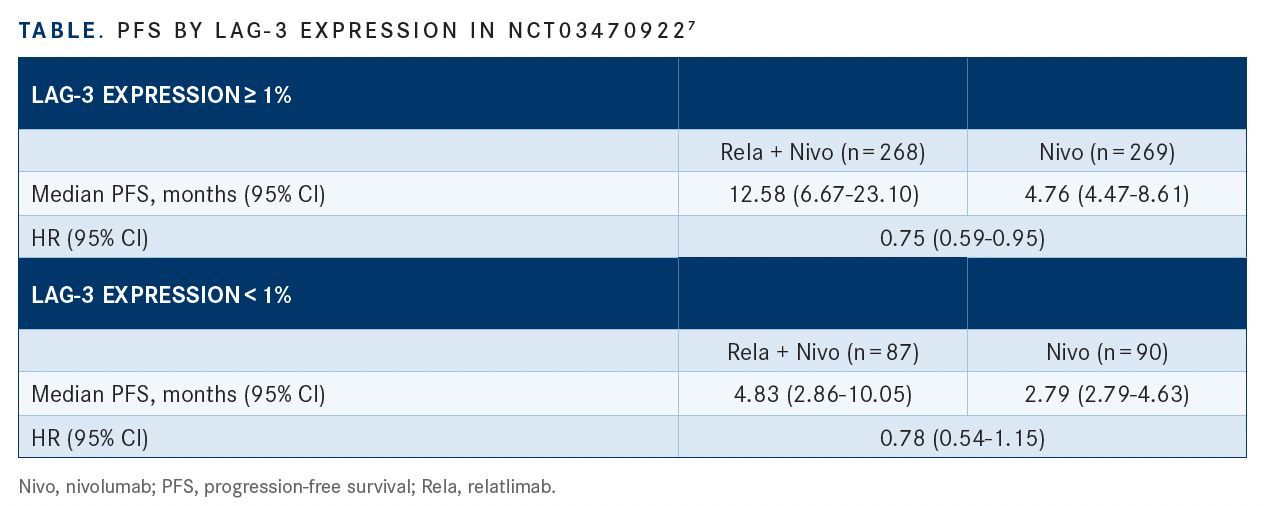

After 12 months, PFS was 47.7% vs 36.0%, respectively, with relatlimab plus nivolumab vs nivolumab alone. According to the investigators, PFS favored the combination across key prespecified subgroups, including stratification by PD-L1 status and LAG-3 expression (TABLE7).

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were 18.9% with relatlimab plus nivolumab vs 9.7% with nivolumab alone, leading to discontinuation of therapy in 14.6% vs 6% of patients, respectively. There were 3 treatment-related deaths with the combination vs 2 with the monotherapy.

Additional efficacy data from the trial presented at ESMO8 reported PFS during the time from randomization to progression on subsequent therapy, which the investigators referred to as PFS2. They also evaluated treatment-free time from last study dose to subsequent therapy.

Median treatment duration was 5.6 months for the combination vs 4.9 months for nivolumab alone. Approximately two-thirds (66.8% and 64.9%, respectively) of patients in each group discontinued treatment, mainly due to disease progression (36.3% with combination vs 46.0% with nivolumab alone). Of the patients, 27.9% and 29.8%, respectively, received subsequent systemic therapy including PD-1 or CTLA-4 inhibitors (9.0% vs 12.8%) and BRAF/MEK therapies (11.5% vs 13.9%).

The relatlimab plus nivolumab combination showed a benefit with respect to PFS2, with the median not reached (95% CI, 21.8-NA) vs 20.0 months (95% CI 15.4-25.1) with nivolumab alone (HR 0.7; 95% CI, 0.61-0.97). Median treatment-free time from last study dose to subsequent therapy was 3.98 months (95% CI, 2.10-7.43) with the combination vs 1.45 months (95% CI 1.25-1.71) with nivolumab alone (HR 0.63; 95% CI, 0.48-0.83).

These results suggest that relatlimab and nivolumab had enduring benefit beyond initial treatment and prolonged benefit beyond first progression, including longer time to initiation of subsequent treatment, the investigators concluded.

“Given that the toxicity for the combination was only marginal over nivolumab alone, this would suggest that nivolumab plus relatlimab is likely to replace nivolumab monotherapy in the treatment of metastatic melanoma,” Luke said. He added, “with that being said, in my practice, high-risk patients, such as those with brain metastases, high lactate dehydrogenase, or rapid progression will still be treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab [Yervoy], at least for the time being, given the robust long-term data for that combination.”

Because of the clinical trial design of RELATIVITY-047, “with a hierarchical testing algorithm of PFS followed by overall survival and then overall response rate, only PFS data are available at the current time,” Luke said. “In addition, more detailed analysis of the tumor microenvironment will be very important to better understand which tumors are most likely to benefit (or not benefit) from adding anti–LAG-3 antibodies ,” Luke said.

Ongoing Phase 2 Studies

Results from several phase 2 studies also have indicated encouraging data for LAG-3– directed approaches, including eftilagimod alpha and tebotelimab.

Eftilagimod alpha is a soluble LAG-3 protein that mediates antigen presenting cell and CD8 T-cell activation, potentially boosting antitumor responses to pembrolizumab (Keytruda). In the second line of the phase 2 TACTI-002 study (NCT03625323), investigators evaluated eftilagimod alpha in combination with pembrolizumab in patients previously treated with platinum-based therapy for metastatic squamous head and neck carcinoma.9

Among the 35 evaluable patients, the objective response rate was 31.4% (95% CI, 16.9%- 49.3%); median PFS was 2.1 months, and 35% of patients showed no progression at 6 months. Common TEAEs were cough (18%), asthenia (16%), dyspnea (11%), fatigue (13%), diarrhea (11%), hypothyroidism (11%), upper respiratory tract infection (11%), and back pain (11%).10

In the first line of the TACTI-002 study, investigators evaluated eftilagimod alpha and pembrolizumab in patients with PD-L1 unselected metastatic non–small cell lung carcinoma in the first-line setting.10 Response rate based on PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) was 27% for patients with TPS less than 1%, 39% for TPS greater than or equal to 1% to 49% and 54% for greater than or equal to 50% TPS. Median PFS for 36 patients was 8.2 months and median OS was not yet reached. The most common TEAEs were asthenia (47%), cough (36%), decreased appetite (36%), dyspnea (32%), pruritus (31%), fatigue (28%), diarrhea (25%), anemia (25%), constipation (25%), and back pain (22%).

Many Additional Studies Upcoming

Upcoming studies include the phase 2/3 MAHOGANY trial (NCT04082364) evaluating the LAG-3–directed agent tebotelimab in patients with gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction cancer.11,12 Tebotelimab has been engineered to bind PD-1 and LAG-3 concomitantly or independently and to disrupt nonredundant inhibitory pathways to further restore exhausted T-cell function.13

The MAHOGANY study is evaluating the Fc-modified anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody margetuximab (Margenza) combined with tebotelimab or the anti–PD-1 retifanlimab. The trial is expected to enroll 860 participants with an estimated primary completion date of May 2024. A phase 2 study (NCT04552223) of relatlimab in combination with nivolumab in 27 patients with metastatic uveal melanoma is also under way.14,15 Main eligibility criteria include patients with biopsy-confirmed metastatic uveal melanoma previously untreated with anti–PD-1, CTLA-4 and/or LAG-3 blocking antibodies and in good performance status. Treatment will be administered until disease progression or intolerable toxicity for up to 24 months. Estimated primary study completion date is December 2023.15

Several additional agents are in phase 1 trials including LBL-007, which is being evaluated in patients with advanced solid tumors.16 Favezelimab (MK4280) is being evaluated in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with previously treated advanced microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer.17 Fianlimab (REGN3767) is being evaluated in combination with cemiplimab in advanced melanoma.18 Other agents being evaluated include IBI11019 and BI 754111.20

LAG-3 and The Future

“The future of immune-oncology combinations appears to be very bright across tumor types,” Luke said. Of note, “the implications from RELATIVITY-047 of adding relatlimab to nivolumab has potential major implications across cancer types,” he added.

“From an immunological rationale and clinical safety perspective, it would make sense that this combination should be able to replace nivolumab across tumor types and in combination with other treatments such as chemotherapy, similar to what is expected for anti-TIGIT antibodies such as tiragolumab and vibostolimab,” Luke said.

REFERENCES:

1. National Cancer Institute. Immune checkpoint inhibitors. Accessed October 7, 2021. https://bit.ly/3FHFHjW

2. Zaremba A, Eggermont AMM, Robert C, et al. The concepts of rechallenge and retreatment with immune checkpoint blockade in melanoma patients. Eur J Cancer. 2021;155:268-280. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.07.002

3. Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168(4):707-723. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017

4. Wang M, Du Q, Jin J, Wei Y, Lu Y, Li Q. LAG3 and its emerging role in cancer immunotherapy. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11(3):e365. doi:10.1002/ctm2.365

5. Burugu S, Dancsok AR, Nielsen TO. Emerging targets in cancer immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;52(Pt 2):39-52. doi:10.1016/j. semcancer.2017.10.001

6. Maruhashi T, Sugiura D, Okazaki IM, Okazaki T. LAG-3: from molecular functions to clinical applications. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e001014. doi:10.1136/jitc-2020-001014

7. Lipson EJ, Tawbi HAH, Schadendorf D, et al. Relatlimab (RELA) plus nivolumab (NIVO) versus NIVO in first-line advanced melanoma: primary phase III results from RELATIVITY-047 (CA224-047). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):9503. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.9503

8. Hodi FS, Tawbi HA, Lipson EJ, et al. Relatlimab (RELA) + nivolumab (NIVO) vs. NIVO in previously untreated metastatic or unresectable melanoma: Additional efficacy in RELATIVITY-047. Presented at: European Society for Medical Oncology Annual Meeting; September 16-21, 2021; virtual.

9. Brana I, Forster M, Lopez-Pousa A, et al. Results from a phase II study of eftilagimod alpha (soluble LAG-3 protein) and pembrolizumab in patients with PD-L1 unselected metastatic second-line squamous head and neck carcinoma). Presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 4-8, 2021; virtual.

10. Clay TD, Majem M, Felip E, et al. Results from a phase II study of eftilagimod alpha (soluble LAG-3 protein) and pembrolizumab in patients with PD-L1 unselected metastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):9046. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.9046

11. Catenacci DVT, Rosales MK, Chung HC, et al. Margetuximab (M) combined with anti-PD-1 (retifanlimab) or anti-PD-1/LAG-3 (tebotelimab) +/- chemotherapy (CTX) in first-line therapy of advanced/ metastatic HER2+ gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) or gastric cancer (GC). Presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 4-8, 2021; virtual.

12. Catenacci DVT, Rosales M, Chung HC, et al. MAHOGANY: margetuximab combination in HER2+ unresectable/metastatic gastric/ gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Future Oncol. 2021;17(10):1155-1164. doi:10.2217/fon-2020-1007

13. MacroGenics. Tebotelimab (PD-1 Å~ LAG-3). Accessed October 7, 2021. https://bit.ly/3mODU42

14. Lutzky J, Fuen LG, Magallanes N, Kwon D, Harbour JW. NCT04552223: a phase II study of nivolumab plus BMS-986016 (relatlimab) in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma (UM) (CA224-094). Presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 4-8, 2021; virtual.

15. Lutzky J, Feun LG, Magallanes N, Kwon D, Harbour JW. NCT04552223: a phase II study of nivolumab plus BMS-986016 (relatlimab) in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma (UM) (CA224- 094). J Clin Oncol. Published online May 28, 2021. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.TPS9590

16. hi Y, Luo X, Zhou H, et al. Phase I study of LBL-007, a novel anti- human lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3) antibody in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):2523. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.2523

17. Garralda E, Sukari A, Lakhani NJ, et al. A phase 1 first-in-human study of the anti-LAG-3 antibody MK4280 (favezelimab) plus pembrolizumab in previously treated, advanced microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):3584. doi:10.1200/ JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.3584

18. Hamid O, Wang D, Kim TM, et al. Clinical activity of fianlimab (REGN3767), a human anti-LAG-3 monoclonal antibody, combined with cemiplimab (anti-PD-1) in patients (pts) with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):9515. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.9515

19. Zhou C, He Y, Ren S, et al. Phase Ia/Ib dose-escalation study of IBI110 (anti-LAG-3 mAb) as a single agent and in combination with sintilimab (anti-PD-1 mAb) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):2589. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.2589

20. Yamaguchi K, Kang YK, Oh DY, et al. Phase I study of BI 754091 plus BI 754111 in Asian patients with gastric/gastroesophageal junction or esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 3):212. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.3_suppl.212

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More