Patient-Centered Oncology: Working Together for Optimal Outcomes

As cancer therapies have evolved and individualized treatments have de-veloped over time, patient-centered care has become more prevalent, and oncology teams must consider it to maximize the chances of positive patient outcomes.

Guy Maytal, MD

Guy Maytal, MD

As cancer therapies have evolved and individualized treatments have de-veloped over time, patient-centered care has become more prevalent, and oncology teams must consider it to maximize the chances of positive patient outcomes.

Patient-centered care is defined as care that encourages patients to actively participate in their healthcare decisions. When patients are active participants, they are more likely to be satisfied with their care overall and be more adherent to their therapies. But patient-centered care also comprises an approach that individualizes the needs of the patient.1

The field of oncology has never been a stand-alone branch of medicine; medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists frequently work with physicians across specialties for the best possible outcomes for their patients. Approaches to individualized patient-centered care may now involve clinicians addressing issues related to aging, fitness, comorbidities, diet, long-term survivorship, and more, in addition to patients’ systemic therapy regimens.

Managing Mental Health

The treatment of a concurrent psychiatric illness in patients with cancer, whether previously diagnosed or one that developed during cancer treatment, is not new. One study by Susanne Kuhnt, PhD, and colleagues found that the 12-month prevalence of any mental disorder was around 40%, with lifetime rates >50% among all patients with cancer and conditions including depression, anxiety, and addiction.2

Given that newer oncology therapies, including biologics, have turned some cancers into chronic diseases, active treatment can last months, with follow-up treatments potentially lasting for years. This extended survival can bring with it additional psychological or psychiatric stress.

In 2008, the Institute of Medicine issued a policy statement regarding psychiatric and psychological care in its report Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs.3This was followed by an American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer policy in 2015 that required accredited cancer centers to have a program for identifying distressed patients and, when appropriate, referring them to appropriate care.4These and similar guidelines and statements reinforce the changing landscape of cancer treatment and survivorship.5Guy Maytal, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry and chief of integrated care and psychiatric oncology at NewYork- Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, New York, recommended that oncologists have an open, honest conversation with their patients to determine how they are currently coping with their disease and their new reality as a patient with cancer. This conversation includes questions such as “Whom do you turn to for support?” as well as those related to how patients cope with stress, he explained.

“Then you have to look at what the patient says and how they may have to make adaptations during treatment. For example, some people cope [with everyday stresses] by exercising, but that may no longer be an option for some patients [during treatment]…some people cope by drinking,” Maytal said. “[These strategies are] not viable while they are in treatment for cancer. You have to strategize [with the patient] about how they are going to deal with these challenging times.”

Depression screening among patients with cancer is helping to improve care, said Maytal. “The challenge with screening for anything is that you need to be able to do something if you have a positive screen. [For instance], you would never do mammograms unless you had a breast cancer program,” he noted.

Maytal will be delivering his presentation entitled “Meeting the Emotional Needs of Your Patients” this afternoon at 4:05.

Caring for Geriatric Populations

Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki, MD, PhD

Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki, MD, PhD

Approximately 60% of patients with a cancer diagnosis are 65 years or older.3This percentage will climb as individuals live longer, both before diagnosis and subsequently with chronic disease. But as patients age, physical and mental problems may also increase. Oncologists are faced with not only comorbidities but also the possibility of decreased physical and mental function among their patients.

Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki, MD, PhD, chief of Geriatrics Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, both in New York, New York, said in an interview that when physicians are caring for patients in their 70s, 80s, or 90s, they must keep in mind factors affected by age. “[Patients] have different levels of function,” she explained. “They have different levels of frailty, which need to be taken into account when you are proposing treatment.”

Additionally, the disease itself may be affected by age in these patients. “Some [tumors] become more aggressive [because of] a prevalence of unfavorable genomic changes or resistance to chemotherapy,” Korc-Grodzicki wrote in an article.6 “Others, like breast cancer, become more indolent [because of] an increased prevalence of hormone receptorrich tumors and endocrine senescence.” And cancer treatment can exacerbate preexisting medical problems as well as cognitive frailty.

According to Korc-Grodzicki, questions that oncologists must consider include:

• Does the patient’s level of cognition allow consent to treatment?

• Is the patient able to understand and participate in the treatment?

• Does the patient want to be treated or prefer to live out their life with sup-portive treatment?

• Is the patient fit, frail, or somewhere in the middle?

• Can the patient get to and from appointments, and does the patient have support at home for managing meals, chores, and adverse events (AEs)?

As with patients with existing psychiatric conditions, adherence to treatment can be difficult for seniors who do not have the necessary support. The oncology team needs to be aware of this situation, said Korc-Grodzicki. Seniors who cannot get to the clinic on their own or care for themselves after treatments will not be able to attend regular appointments. This leads to a failure of treatment no matter how effective systemic therapies or treating physicians are, she added.

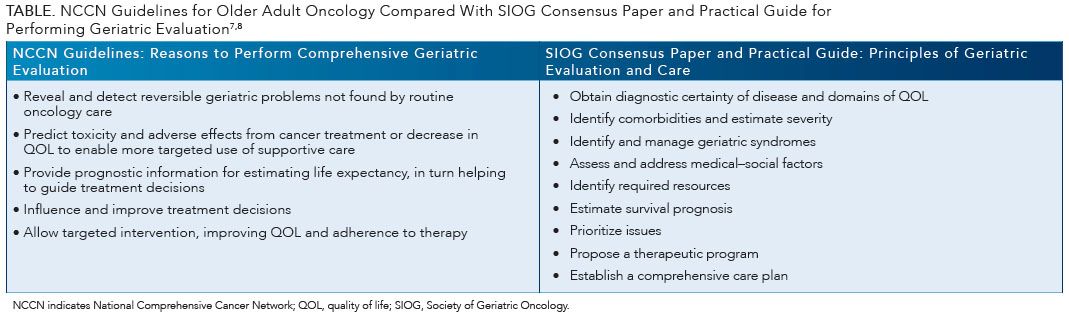

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the International Society of Geriatric Oncology both recommend a geriatric assessment for older patients before starting treatment (TABLE).7,8Korc-Grodzicki pointed to guidelines from theAmerican Society of Clinical Oncologypublished in 2018 in theJournal of Clinical Oncology.9“In their guidelines [for older patients who are going to have chemotherapy], they recommend that all patients over the age of 65 have some geriatric assessment, including assessing their function, how they will be able to take care of themselves, their ability to walk, cognition, and so on. Sometimes it’s not easy to make the distinction unless you dig a little deeper and go a little beyond the usual history and physical and lab work,” she said.

As with psychiatric evaluation, the oncology team needs to be equipped with the necessary resources for a full geriatric assessment, including enough staff members and a plan to follow up on the findings.

Korc-Grodzicki will continue the dialogue about geriatric oncology this afternoon at 4:35.

Addressing Cardiovascular Issues

New cancer treatments are successfully prolonging life for many patients, but in some cases, the trade-offs are possible cardiac, thrombotic, or metabolic complications. The potential for cardiotoxicity has always accompanied chemotherapy, particularly with treatment regimens that have included anthracyclines and radiotherapy.10

Javid J. Moslehi, MD

Javid J. Moslehi, MD

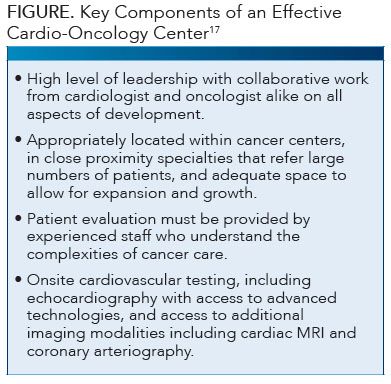

For some patients, treatment brings on cardiac dysfunction; others begin therapy with an existing cardiovascular condition or are at risk of heart disease when they receive their cancer diagnosis. This issue is so important that some physicians have called cardiotoxicity in cancer treatment a public health issue, and this problem has given rise to the medical specialty cardio-oncology.11,12

In a 2013New England Journal of Medicineeditorial, author Javid J. Moslehi, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of cardio-oncology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, noted that even modern radiotherapy techniques developed after 1990 can increase cardiovascular risks.13 Moslehi will be leading clinicians in the discussion about cardio-oncology this afternoon at 3:50.

Moslehi spotlighted one study of 2168 women with breast cancer who had undergone radiation therapy. Investigators observed a proportional increase in the mean radiation dose to the whole heart and the rate of ischemic heart disease, as well as cardiovascular disease risk in both women with cardiac risk factors and those without. However, women with preexisting cardiac risk factors at the time of radiotherapy had a greater absolute increased risk.14

Immune-related AEs (irAEs) of treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors may lead to treatment discontinuation in close to 40% of patients and may rarely involve cardiotoxic events. One 2013 review suggested that myocarditis occurs at a rate of about 1% in patients treated with nivolumab (Opdivo) with or without ipilimumab (Yervoy), with events occurring more commonly in patients treated with the combination.15A more recent study published in Lancet Oncology in 2018 confirmed earlier findings that immune checkpoint inhibitor treatments could lead to severe and disabling inflammatory cardiovascular irAEs, such as myocarditis and pericardial disease, not long after treatment begins.16

Microbiota Effects

As the use of immunotherapeutic strategies increases and incidence rates of cardiovascular irAEs rise, cardio-oncology specialists and dedicated clinics may become an essential part of the treatment paradigm (FIGURE).17

An altered gut microbiota can alter the immune response to tumors and the tumor microenvironment. By monitoring the intestinal microbiota, clinicians may be able to enhance chemotherapy efficacy while reducing toxicity as well as improve sensitivity to immunotherapeutics.18

The effect of abnormal gut microbiota was examined in a study in Science in 2018, and results showed that antibiotics given to patients with advanced cancer undergoing immunotherapy treatment with a PD-1/ PD-L1 inhibitor caused an inhibition of clinical benefit. Patients who received antibiotics before or soon after cancer treatment had significantly lower rates of progression-free survival and overall survival compared with patients who did not take antibiotics.19

Jiyoung Ahn, PhD

Jiyoung Ahn, PhD

Systemic cancer therapies are not the only link to changes in gut microbiota; radiotherapy can also alter the gut environment, potentially affecting tumor response in some cases.20 “Inflammation caused by ionizing radiation can exert either anti- or protumorigenic effects. Additionally, radiotherapy can elicit an antitumor response not only in radiation of target lesions but also in radiation of remote lesions,” wrote the authors of a 2019 article in theChinese Journal of Cancer Research.20

In addition, radiotherapy can affect the gut microbiota to such an extent that it causes serious AEs, which could lead to cessation of treatment. Investigators believe a similarity exists between the effects of radiotherapy on the gut microbiota and those on inflammatory bowel disease, possibly caused by the treatment’s effect on the gut bacteria.21

One study evaluating oral microbiota found a correlation between certain periodontal pathogens and the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma.22“[This] study brings us much closer to identifying the underlying causes of these cancers because we now know that at least in some cases, disease appears consistently linked to the presence of specific bacteria in the upper digestive tract,” said study coauthor Jiyoung Ahn, PhD, associate professor of population health and environmental medicine at the New York University School of Medicine and associate director of population science at Perlmutter Cancer Center, both in New York City. “Conversely, we have more evidence that the absence or loss of other bacteria in the mouth may lead to these cancers or to gut diseases that trigger these cancers.23”

Much more research is needed to elucidate the role of gut microbiota in the efficacy of cancer therapies. An ongoing study in France is exploring the link between gut microbiota, intestinal inflammation, colorectal cancer, bile acid, and liver diseases (NCT02726243). Another study out of Hong Kong is looking at microbiota as it may relate to thyroid cancer (NCT03543891).

As the fields of oncology and patient-centered care are further integrated, multidisciplinary teams are finding that the areas have more in common than they may have realized just a decade ago. As investigators learn more about these connections, treatments may be adjusted and refined to help improve patient response to cancer treatment.

References:

- OMA policy paper: patient-centered Care. Ont Med Rev. 2010;77(6):34-49. omr.dgtlpub.com/2010/2010-06-30/pdf/ omr_2010-06-30.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Kuhnt S, Brähler E, Faller H, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in cancer patients. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(5):289-296. doi: 10.1159/000446991.

- The psychosocial needs of cancer patients. In: Adler NE, Page AEK, eds. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2008:23-50.

- Lazenby M, Ercolano E, Grant M, Holland JC, Jacobsen PB, McCorkle R. Supporting commission on cancer-mandated psychosocial distress screening with implementation strategies. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):e413-e420. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002816.

- McFarland DC, Holland JC. The management of psychological issues in oncology. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2016;14(12):999-1009.

- Korc-Grodzicki B. Geriatric oncology: a geriatrician’s perspective. ASCO Post website. ascopost.com/issues/august-25-2015/geriatric-oncology-a-geriatrician-s-perspective/. Published August 25, 2015. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Older Adult Oncology, version 1.2019. National Comprehensive Cancer Network website. nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/senior.pdf. Published January 8, 2019. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Addressing the quality of life needs of older patients with cancer: a SIOG consensus paper and practical guide. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(8):1718-1726. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy228.

- Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2326-2347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8687.

- Moslehi JJ. Cardiovascular toxic effects of targeted cancer therapies. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1457-1467. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMra1100265.

- Jain D, Russell RR, Schwartz RG, Panjrath GS, Aronow W. Cardiac complications of cancer therapy: pathophysiology, identification, prevention, treatment, and future directions. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19(5):36. doi: 10.1007/s11886-017-0846-x.

- Cardio-oncology: cancer treatment and your heart. CardioSmart/ American College of Cardiology website. cardiosmart.org/Heart- Conditions/Cardio-Oncology. Published November 2017. Accessed October 19, 2019.

- Moslehi JJ. The cardiovascular perils of cancer survivorship. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(11):1055-1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1215300.

- Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P, et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(11):987-998. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209825.

- Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1749-1755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609214.

- Salem JE, Manouchehri A, Moey M, et al. Cardiovascular toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an observational, retrospective, pharmacovigilance study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(12):1579-1589. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30608-9.

- Pudil R. The future role of cardio-oncologists. Card Fail Rev. 2017;3(2):140-142. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2017:16:1.

- Ma W, Mao Q, Xia W, Dong G, Yu C, Jiang F. Gut microbiota shapes the efficiency of cancer therapy. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1050. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01050.

- Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018:359(6371):91-97. doi: 10.1126/science. aan3706.

- Zhang S, Wang Q, Zhou C, et al. Colorectal cancer, radiotherapy and gut microbiota. Chin J Cancer Res. 2019;31(1):212-222. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2019.01.16.

- Ferreira MR, Muls A, Dearnaley DP, Andreyev HJN. Microbiota and radiation-induced bowel toxicity: lessons from inflammatory bowel disease for the radiation oncologist. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):e139-e147. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70504-7.

- Peters BA, Wu J Pei Z, et al. Oral microbiome composition reflects prospective risk for esophageal cancers. Cancer Res. 2017;77(23):6777-6787. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1296.

- Ahn J. Researchers identify bacteria tied to esophageal cancer. NYU Langone Health website. nyulangone.org/news/researchers-identify-bacteria-tied-esophageal-cancer. Accessed October 21, 2019.