New Quality Initiative for Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer Improves Care, Coordination

Twenty to 30 years ago, delivering a diagnosis of lung cancer to a patient was a difficult conversation to have for many oncologists. But that has given way to greater optimism today, according to Mark A. Socinski, MD.

Mark A. Socinski, MD

Mark A. Socinski, MD

Twenty to 30 years ago, delivering a diagnosis of lung cancer to a patient was a difficult conversation to have for many oncologists. But that has given way to greater optimism today, according to Mark A. Socinski, MD, executive medical director of AdventHealth Cancer Institute located in central Florida.

“If we can get the right treatment to the right patient at the right time, we can see an improvement in survival in which patients who [in the past] were living for months are now living for years,” Socinski said during an interview withTargeted Therapies in Oncology.

Greater use of lung cancer screening techniques and improved treatment options have contributed to a more optimistic attitude, Socinski said. “This is a disease in which you can decrease mortality by screening, which we have been doing in [other cancers such as] breast cancer, colon cancer, and prostate cancer.”

Improved treatment options are linked to advances in molecular testing that are now available to the oncologist in the community setting. “One of the important developments in NSCLC is there are a few alterations that have FDA-approved targeted therapies,” he said. Now, a new quality initative can help oncologists effectively use these advances.

National Quality Care Initiative

Although progress in identifying subtypes of NSCLC and molecular biomarkers has led to changes in diagnosis and staging, treatment planning and decision making have become more complex, according to the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC).1 Adding to the complexity is the fragmentation of the US healthcare system that can impede consistent access to care for patients. In light of this complexity, the ACCC has launched a national quality care initiative for patients with stage III and stage IV NSCLC.

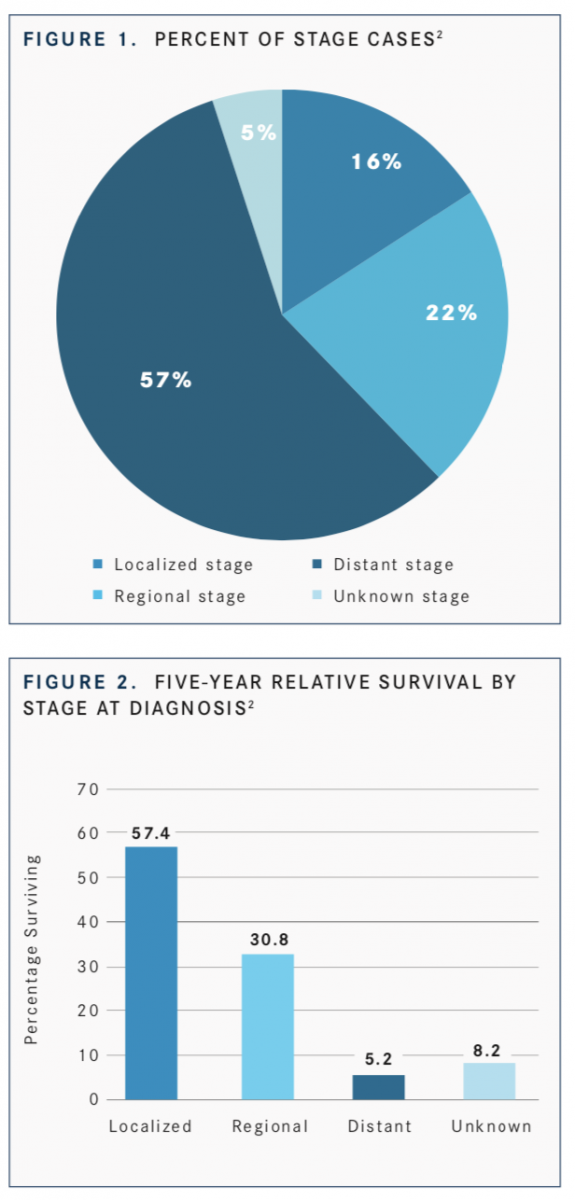

To foster greater interdisciplinary communication and care coordination, a multiphase initiative, “Fostering Excellence in Care and Outcomes in Patients With Stage III and IV NSCLC,” will identify barriers to providing optimal care, guidance, and support for process improvement projects for community oncologists, who provide care for 80% to 85% of patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. According to the National Cancer Institute, the earlier lung and bronchus cancer is diagnosed, the better chance a person has of surviving 5 years after the diagnosis. For these cancers, 16.4% of patients are diagnosed at the local stage. The 5-year survival for localized lung and bronchus cancer is 57.4% (FIGURES 1and2).

The project will include process improvement models developed and tested across a variety of care settings, from large academic institutions to smaller community programs and practices. The ACCC will partner with the American College of Chest Physicians, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and LUNGevity Foundation to develop these programs. The project is made possible by support from AstraZeneca.

Caring for patients throughout their lung cancer journey requires interdisciplinary communication and coordination among multiple medical disciplines, including primary care physicians, pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, pathologists, radiologists, medical oncologists, interventional oncologists, radiation oncologists, nurse navigators, genetic counselors, and social workers. Regarding the new initiative, “we are trying to identify the barriers in practice and opportunities for education,” Socinski said.

An initial survey conducted for this project yielded robust cross-discipline responses providing data about current practice patterns, gaps, and barriers to care coordination and communication. In addition, the survey revealed other systemic processes that can hinder timely adoption of advances in staging, biomarker testing, and treatment planning for NSCLC. The survey was designed to elucidate the current state of lung cancer diagnosis and treatment, Socinski said, and identify areas where oncologists can improve.

A steering committee will identify 6 cancer programs to serve as process improvement sites. These sites will create and execute process improvement models aimed at overcoming identified barriers to excellence in care for patients with these stages of disease. The models tested will be applicable across care settings. Results will be shared with the wider oncology community.

To improve care and outcomes for patients with stage III and IV NSCLC, improved process pathways for integrated interdisciplinary communication and care coordination are essential.

Comprehensive Molecular Testing

Despite all these advances, there are gaps where care and communication can falter.

Socinski said that in his practice all patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC receive comprehensive molecular testing to determine if they have any molecular alterations. In the community setting, that diagnostic approach is not always implemented to its full extent.

“One of the best things an oncologist can do for their [patient with] lung cancer is diagnose a molecular alteration that has a targeted therapy,” Socinski said. “In general, I can say that if you have a target and use a targeted therapy, the response rates in progression-free survival and survival experience [are] far superior [compared with] chemotherapy.”

Socinski noted that although interpreting molecular testing results can be difficult, an even more basic challenge is obtaining enough tissue sample to have the molecular testing completed. “One of the barriers that we [face] is tissue acquisition,” he said. “Samples are usually collected by surgeons, intervention radiologists, or pulmonologists who have varying levels of understanding about the molecular testing needs for [patients with] lung cancer.”

If an inadequate tissue sample is obtained, the oncologist faces a dilemma: Should a second biopsy be ordered? “Most patients with lung cancer are older, they have comorbidities, and sometimes biopsies can be risky,” he said.

An option to consider is liquid biopsy, Socinski said. Liquid biopsy plays a significant role in the diagnosis of lung cancer, but there remains “an educational need about the use of liquid biopsy that should be spread among community oncologists,” he said.

An Explosion in Our Understanding

There has been an explosion in the understanding of the biology of lung cancer. Historically, it was believed that all lung cancer was 1 disease. That has changed, as lung cancer has been now been identified as many diseases, with many subcategories.

Although nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been a broad term adopted by many, “some experts suggest that we should use more precise terminology. For example, we should identify the patient as EGFR-mutation positive or RET-fusion positive,” Socinski said. “We now understand that once we start parsing out the different subsets, identifying the most effective therapy can improve outcomes dramatically.”

Another barrier was the belief that the disease was predominantly a tobacco-smoker’s disease, with a characteristic stigma that it was self-inflicted, despite the statistics that show a majority of smokers do not develop the disease. “Smoking contributes to the risk of developing lung cancer, but it’s not a guarantee that you develop it,” Socinski said.

“The ACCC wants to help community oncologists. I think there are areas in which we are not providing our patients with state- of-the-art treatments,” Socinski said. Through this initiative, the ACCC is improving care and “ensuring every patient with the disease is receiving quality-directed care.”

References

- Association of Community Cancer Centers. Association of Community Cancer Centers collaborates with AstraZeneca to launch national initiative to support quality care initiative for stage III and IV non-small cell lung cancer [press release]. Rockville, MD: PR Newswire; June 11, 2019. prn. to/2LPRyUi. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: lung and bronchus cancer. NCI website. bit.ly/2mWbmbd. Accessed July 28, 2019.

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More