New Guidelines Divide Recommendations for Driver and Nondriver NSCLC

In 2017, the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Ontario Health-Cancer Care Ontario's non–small cell lung cancer expert panel published a guideline with recommendations for systemic therapy for patients with stage IV NSCLC.

In 2017, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the Ontario Health-Cancer Care Ontario (OH-CCO)’s non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) expert panel published a guideline with recommendations for systemic therapy for patients with stage IV NSCLC.1 Soon after publication, clinicians clamored for another update. With the fast pace of discovery of new immunotherapies and targets, the standard of care was changing so rapidly that “it left clinicians in a lurch about how to incorporate these, in what order, and in what patient population,” Bryan J. Schneider, MD, clinical professor of internal medicine in the Division of Hematology/Oncology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, expert panel member, and guidelines coauthor said in an interview with Targeted Therapies in Oncology. “More than most of the other tumor types, we’ve seen exponential leaps and bounds in the positive trials that have led to new standards of care in NSCLC.”

The topic became so broad and deep, with different subsets of NSCLC, that the committee divided the guidelines into 2: one for NSCLC with driver gene alterations and one without. “We thought it would be better for providers if we divided them among the first decision point they face when you have a patient with advanced NSCLC. Is there an actionable gene alteration or not? It drives all the treatment decision-making downstream,” Schneider said.

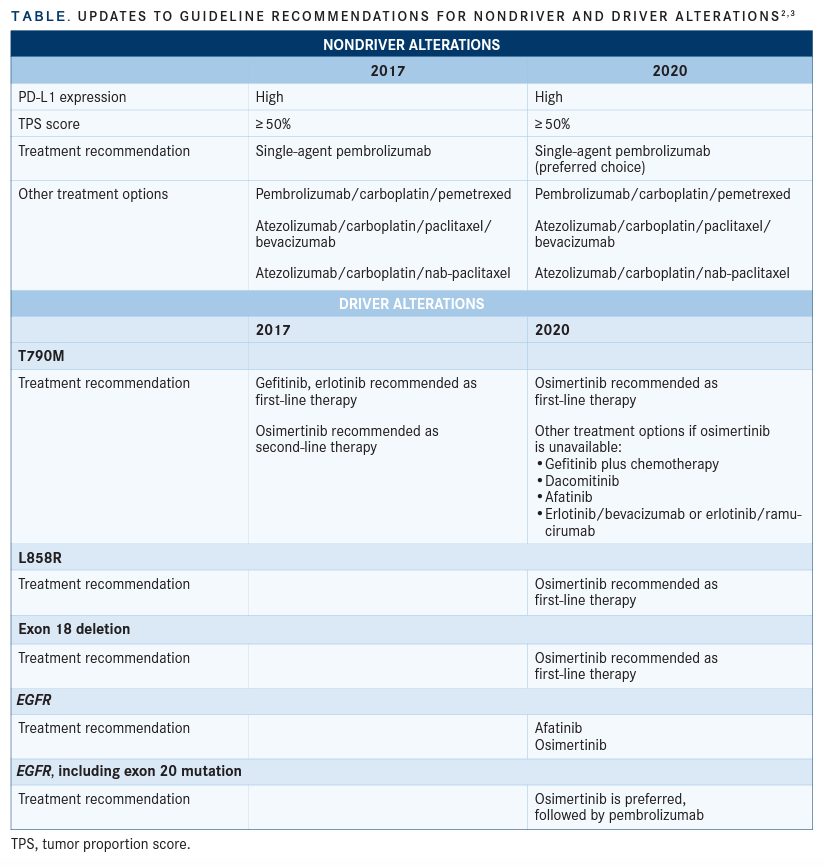

The update for treating for patients without driver alterations2 was published in 2020, and the guideline for patients with driver alterations3 was published in 2021 (TABLE2,3).

Advanced NSCLC Without Driver Gene Alterations

These nondriver alteration guidelines include more data about incorporating immune checkpoint inhibitors, Schneider said. Prior to 2017, immune checkpoint inhibitors were typically used as monotherapies in second-line treatments for patients who progressed on chemotherapy. Since that 2017 update, additional clinical trial data became available for using immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy and as monotherapy in the frontline setting.

These new recommendations are based on the degree of PD-L1 tumor expression, ie, tumor proportion score (TPS) test results. This was challenging, Schneider said, because the trials used different assays and different cutoff points for what was considered positive PD-L1. For this set of guidelines, “we tried to simplify recommendations based on consistent cut-off points,” he said. “If there’s a newly diagnosed patient with metastatic NSCLC and they do not have any actional driver gene alterations, what is the optimal treatment approach based on their PD-L1 status?”

The panel conducted a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from December 2015 to 2019, ultimately using 5 RCTs as the evidence base: KEYNOTE-042 (NCT02220894), KEYNOTE-189 (NCT02578680), KEYNOTE-407 (NCT02775435), IMpower150 (NCT02366143), and IMpower130 (NCT02367781). Interventions include immune checkpoint therapy, chemotherapy, and antiVEGF agents. The panel addressed the most effective therapies for first line, second line, and potentially third line/beyond.

The following highlights the notable changes in the guidelines.

Recommendations 1.1-1.4

These recommendations focus on patients with high PD-L1 expression (TPS ≥ 50%) and nonsquamous cell carcinoma (non-SCC) in the absence of contraindications to immune checkpoint therapies. The panel recommended single-agent pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in the first-line setting. Additional treatment options include pembrolizumab/carboplatin/pemetrexed, atezolizumab (Tecentriq)/carboplatin/ paclitaxel/bevacizumab (Avastin), or atezolizumab/carboplatin/nab-paclitaxel.

The 2017 guidelines include monotherapy pembrolizumab as an option, but the 2020 guidelines present this as the preferred choice, based on new evidence from the KEYNOTE-042 trial and updated results from KEYNOTE-024 (NCT02142738). These trials showed an overall 2-year survival improvement on pembrolizumab, along with a superior toxicity profile compared to chemotherapy.

“All things being equal, the preference is single-agent pembrolizumab,” Schneider said, adding that a patient with a high tumor burden and a lot of symptoms may benefit from combination therapy however, as chemotherapy can elicit a response more rapidly than immunotherapy alone.

Recommendations 2.1-2.6

These recommendations focus on patients with non-SCC and either negative (0%) or low positive (1%-49%) PD-L1 expression. The 2.2 pembrolizumab/carboplatin/pemetrexed recommendation is based on a subset analysis of the KEYNOTE-189 study, which demonstrated an improvement in 1-year survival when pembrolizumab was added to carboplatin and pemetrexed. The 2.3 atezolizumab/carboplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab recommendation is based on the IMpower150 study, given the response rate and interim median overall survival (OS) improvement. The panel noted that it is a good option for patients with a contraindication to pemetrexed.

The 2.4 atezolizumab/carboplatin/nabpaclitaxel recommendation is based on the IMpower130 trial, which showed clinical benefit over carboplatin/nab-paclitaxel alone.

For the 0% to 49% PD-L1 expression group, “looking at the quality of evidence, chemotherapy needs to be part of the treatment plan because the clinical benefit of immunotherapy alone is there, but it’s low,” Schneider said. Only one-third of patients have high PD-L1 expression, he said, and the other two-thirds will need chemotherapy in addition to an immune checkpoint inhibitor. “There are a lot of different regimens out there, and they haven’t been compared head-to-head, but they have meaningful clinical benefits for the patients. The guidelines leave some of that to the discretion of the clinician.”

Recommendations 4.1-4.4

These recommendations focus on patients with negative (TPS 0%) and low positive (TPS 1%-49%) PD-L1 expression, SCC, and ECOG performance status 0 to 1, with 4.1 recommending pembrolizumab/carboplatin/paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel. This is based on KEYNOTE-407, in which PFS and OS results were better than chemotherapy alone.

Recommendation 4.2 includes patients with contraindications to immunotherapy; clinicians should offer standard chemotherapy with platinum-based 2-drug combinations per the 2015 update. Recommendation 4.3 is also for patients with contraindications to immunotherapy who are not deemed candidates for platinum-based therapy; clinicians should offer standard chemotherapy with non–platinum-based 2-drug combinations, per the 2015 update.

Advanced NSCLC With Actionable Genomic Alterations This guideline, published in 2021, is almost completely new due to the identification and development of more targeted therapies to address specific actionable gene alternations, Schneider said. It includes 7 targets, 4 of which were covered in the 2017 update: EGFR exon 19 deletion, exon 21 L858R, and exon 20 T790M; ALK; ROS1; and BRAF V600E. This update also covers driver alteration targets: MET exon 14 skipping mutations, RET, and NTRK fusions.

Approximately 25% of patients with lung cancer tumors have driver alterations,4 but data presented at 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting suggested that not all lung cancer patients received driver testing, though they should, Schneider said. “Patients need to have this full biomarker profile, not just with PD-L1, EGFR, and ALK, but the other drivers, since there are FDA-approved drugs that target these that could potentially spare the toxicity of chemotherapy.”

“I know it can be challenging to obtain enough tumor tissue for analysis and not all driver alterations may be assessed based on the platform used. Plus, many of these are exceedingly rare. But if they’re found, it’s a significant game changer for patient prognosis and treatment options,” he said.

Recommendations 1.1-1.9 These recommendations focus on patients with EGFR driver alterations with an ECOG performance status of 0 to 2. Recommendation 1.1 suggests that in the first-line setting, patients with T790M, L858R, or exon 19 deletion mutations should be offered osimertinib (Tagrisso). This is based on evidence in the FLAURA trial (NCT02296125), which showed PFS and OS improvement and fewer adverse events compared with first-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) comparators like gefitinib (Iressa) or erlotinib (Tarceva) as well as improved PFS compared with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy. In the 2017 guidelines, osimertinib was only recommended as second-line therapy for people with T790M mutations.

If osimertinib is unavailable, recommendations 1.2-1.3 suggest using gefitinib with chemotherapy or dacomitinib (Vizimpro) monotherapy. These options will improve PFS and OS compared with a first-generation EGFR-TKI monotherapy option, based on several RCTs. The ARCHER1050 (NCT01774721) trial supported using dacomitinib monotherapy over gefitinib, although some adverse events increased. Other options in recommendations 1.4-1.5 include afatinib (Gilotrif) or erlotinib/bevacizumab or erlotinib/ramucirumab (Cyramza) or gefitinib, erlotinib, or icotinib (Conmana).

The most common mutation identified is EGFR. Those with access to osimertinib receive it as first-line therapy. “The [adverse] effect profile for osimertinib is very manageable, which is important, as this medication is taken on a daily basis, potentially for years,” he said.

Recommendation 1.6 includes patients with a ECOG performance status of 3; panelists suggest an EGFR-TKI. “Oftentimes, treatment decisions are based on performance status of patients.” Schneider said. “If patients are symptomatic from cancer and have mutation like EGFR, utilizing one of these TKIs can afford rapid improvement of symptoms in days to a couple of weeks. For those with a marginal performance status, you can still offer this with the hopes it can help improve the quality of life.”

Recommendation 1.7 applies to patients with EGFR mutations other than exon 20 insertion mutations, T790M, L858R, or exon 19 deletion alterations. The panel recommends afatinib or osimertinib or treatments outlined in the ASCO/OH-CCO nondriver mutation guideline. “Ninety percent of these EGFR mutations are L858R or exon 19 deletions. Afatinib has been shown to have some clinical benefit.”

Recommendation 1.8 applies to patients with any activating EGFR mutation, including exon 20 insertion mutations, regardless of PD-L1 expression levels. In these situations, single-agent immunotherapy should not be used. Schneider said the panel felt this was important because some patients get biomarker testing done in one fell swoop. “It’s not uncommon to have high PD-L1 expression and an EGFR mutation. It led to confusion in the community,” he said. Clinicians were unsure whether to offer osimertinib because of the EGFR mutation or single-agent pembrolizumab because of the high PD-L1 expression level. “I think the data really [support] that in our patients who have an EGFR mutation, PD-L1 expression has not been a very good biomarker to predict response to immunotherapy. Regardless of PD-L1 status, if the patient has an EGFR mutation, that drives treatment options, not PD-L1 status,” he said, noting that they’ve seen more concerning data that patients who start with a PD-L1 inhibitor and are subsequently treated with an EGFR inhibitor are at much higher risk for adverse events, particularly pneumonitis.

Recommendation 1.9, the final one in this section, is for those with driver alterations causing resistance to first- and second-generation EGFR-TKIs. The panel recommends doublet chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab or standard treatment outlined in the ASCO/ OH-CCO nondriver mutation guideline for patients with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations.

“Oftentimes providers want to know the current standard of care if the patient has progressed on an EGFR-TKI,” Schneider said.

“Most of the clinical trials that are investigating immune checkpoint inhibitors, with the exception of IMpower150, excluded patients with EGFR mutations and ALK-positive mutations. So we don’t know the role of incorporating immune checkpoint TKIs after they progress. It’s still an area of active investigation.” If a patient runs out of EGFR-TKI options, they would receive platinum-based chemotherapy.

Recommendations 2.1-2.2

These recommendations include second-line treatment for patients with EGFR driver alterations. For those with a T790M mutation at the time of progressive disease who did not receive osimertinib, osimertinib should be offered. Patients with any EGFR mutation who progressed on EGFR-TKIs and did not have T790M mutations or those who progressed on osimertinib should receive treatment based on the ASCO/OH-CCO nondriver mutation guideline.

“Osimertinib, when under development, was looked at as a means to salvage patients who progressed on a first- or second-generation TKI,” Schneider said.

“They found that up to 60% of patients who progressed on early generation EGFR TKIs had a resistance mutation, T790M, and osimertinib actually still had activity [in these patients]. We wanted to stress that if a patient was treated in the front line with an earlier-generation TKI and progressed, repeat [next-generation sequencing] testing to look for T790M and if positive, to treat with osimertinib.”

Recommendation 3.1

This recommendation covers patients with ALK driver alterations and a ECOG performance status of 0 to 2. Guidelines recommend offering alectinib (Alecensa) or brigatinib (Alunbrig) in the first-line setting, and if these are not available, offering ceritinib (Zykadia) or crizotinib (Xalkori).

High-quality data are available for this recommendation, especially for alectinib, Schneider said. The agent is well tolerated and with a good central nervous system penetration, “so it actively treats brain metastases, which is a common site of failure for the initial drug approved for ALK-positive disease, crizotinib.”

Recommendations 4.1-4.3

This line of recommendations involves ALK rearrangement for patients with an ECOG performance status of 0 to 2 who previously received alectinib or brigatinib. These patients can be offered lorlatinib (Lorbrena) in second-line treatment. If crizotinib was given in the first-line setting, alectinib, brigatinib, or ceritinib should be offered. If crizotinib was given in the fi rst-line setting and alectinib, brigatinib, or ceritinib was given in the second-line setting, the guidelines recommend lorlatinib as the third-line setting or standard treatment based on the ASCO/OH-CCO nondriver mutation guideline. While developing the guidelines, lorlatinib, the newest generation of ALK inhibitor was being developed and had some activity in patients who progressed, Schneider said.

Recommendations 5.1-5.3

For patients with ROS1 rearrangement, crizotinib, or entrectinib (Rozlytrek) should be offered in the first-line setting or standard treatment based on the ASCO/OH-CCO nondriver mutation guideline. They can also be offered ceritinib or lorlatinib. Patients should be tested for ROS1, Schneider said. “Crizotinib and entrectinib have low-level data but durable responses to these therapies are commonly achieved and should be offered to these individuals,” he said.

Recommendations 6.1-6.2

These recommendations focus on second-line treatments for patients with ROS1 rearrangement and ECOG performance status of 0 to 2. If the patient received first-line ROS1-targeted therapy, they should receive standard treatment based on the ASCO/OH-CCO nondriver mutation guideline for second line. If given nontargeted therapy in the first-line setting, they should be offered crizotinib, ceritinib, or entrectinib in the second line. The EUROCROSS trial (NCT02183870) and METROS trials (NCT02499614) were used for these recommendations. The review identifi ed no RCTs com-paring targeted agents like crizotinib, entrectinib, ceritinib, or lorlatinib with chemotherapy or chemotherapy/immunotherapy. They found no RCTs directly comparing 2 ROS1 inhibitor therapies.

Recommendations 7.1-7.2

These recommendations refer to the BRAF V600E mutations. In the first-line setting, the guidelines recommend dabrafenib (Tafi n-lar)/trametinib (Mekinist) or standard first-line treatment based on the ASCO/OH-CCO non-driver mutation guideline.

The guidelines for BRAF V600E and the remain-ing gene alterations recommend targeted therapy either before or after platinum-based chemotherapy. Many of the trials investigated these agents after progression on frontline chemotherapy so data on use of these agents as initial therapy is very limited, Schneider said. “Sometimes clinicians are unsure of the optimal frontline treatment.”

The panel filt it was reasonable to start with a targeted agent or start with standard platinum-based chemotherapy. Either way, you should offer the other treatment in the second-line setting.

For example, if a patient with a BRAF V600E mutation is started on platinum-based chemotherapy but is responding and tolerating the chemotherapy, it’s reasonable to continue on that and consider dabrafenib/trametinib as second-line therapy. This would be a similar approach for MET exon 14 skipping mutations, RET and NTRK fusions and their respective targeted therapies., Schneider noted.

Recommendations 9.1-9.2

This set of recommendations focuses on patients with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. Patients should be offered either MET-targeted therapy of capmatinib (Tabrecta) or tepotinib (Tepmetko) as first-line treatment or standard treatment based on the ASCO/OH-CCO nondriver mutation guideline.

Recommendations 10.1-10.2

In the second-line setting, patients with MET abnormalities other than exon 14 skipping mutations or those given MET-targeted therapy in the frontline setting should receive standard treatment based on the ASCO/OH-CCO nondriver mutation guideline.

Piloting a Living Guideline Program

Just as the 2017 guidelines needed updating soon after they were published, research continues to move quickly. For this reason, ASCO is piloting a living guideline program for NSCLC and immunotoxicity guidelines.

“We’re looking to update these in real time, or potentially quarterly, when practice-changing data emerge like the recent approval of sotorasib for KRAS G12C positive advanced NSCLC,” Schneider said. Ideally the guidelines would be updated on the ASCO website.

“Then eventually when there are a critical mass of changes, there would be a normal guideline update in JCO, like we have here. The goal of the living guideline program would be to provide current treatment recommendations in a world where standard of care may change every few months.”

References:

1. Hanna N, Johnson D, Temin, S, et al. Systemic therapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical prac-tice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3484-3515. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.74.6065

2. Hanna NH, Schneider BJ, Temin S, et al. Therapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer without driver alterations: ASCO and OH (CCO) joint guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(14):1608-1632. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.03022

3. Hanna NH, Robinson AG, Temin S, et al. Therapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer with driver alterations: ASCO and OH (CCO) joint guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(9):1040-1091. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.03570

4. Lung cancer genomic testing (EGFR, KRAS, ALK). Memorial Sloan Ket-tering Cancer Center. Accessed June 16, 2021. https://bit.ly/3gHKAxI