First Randomized Clinical Trial Evaluating Geriatric Assessment Reveals High Satisfaction With Communication About Aging-Related Concerns

Integrating a geriatric assessment into the care of older adults who are receiving cancer treatment in communi­ty oncology practices improves patient and caregiver satisfaction and encourages commu­nication about aging-related concerns, accord­ing to results of a clinical trial that enrolled 541 patients with advanced cancer.

Supriya G. Mohile, MD, MS

Supriya G. Mohile, MD, MS

Integrating a geriatric assessment (GA) into the care of older adults who are receiving cancer treatment in communi­ty oncology practices improves patient and caregiver satisfaction and encourages commu­nication about aging-related concerns, accord­ing to results of a clinical trial that enrolled 541 patients with advanced cancer.

Oncology practices within the University of Rochester National Cancer Institute Commu­nity Oncology Research Program network par­ticipated in the study (NCT02107443) and were cluster randomized to receive either a tailored GA summary with recommendations for each enrolled patient or alerts only for patients meet­ing criteria for depression or cognitive impair­ment based on national guidelines.1 Seventeen practices were designated for the intervention arm, which consisted of 64 oncologists and 296 patients, and 14 practices were designated for the usual practice control arm, which con­sisted of 68 oncologists and 250 patients.

Because the study population comprised older adults with advanced cancer who have aging-related conditions, lead author Supriya G. Mohile, MD, MS, the Philip and Marilyn Weh­rheim Professor of Medicine and Surgery at the Wilmot Cancer Institute, University of Rochester, New York, thought oncologists and healthcare providers would be particularly interested in participating and gaining insight. Additionally, Mohile emphasized that this was a population with below-average rates of partici­pation in clinical trials.

“That’s why the doctors cared about this issue, about this study and its outcomes,” said Mohile in an interview withTargeted Thera­pies in Oncology. “This is the first randomized clinical trial [evaluating] geriatric assessment in older patients with advanced cancers, [that has shown improvement in] patient-centered outcomes and caregiver satisfaction.”

Patients participating in clinical trials are often younger and more fit than those in the community, said Mohile. “How does the commu­nity oncologist extrapolate data from those trials and apply [them] to the real-world population?”

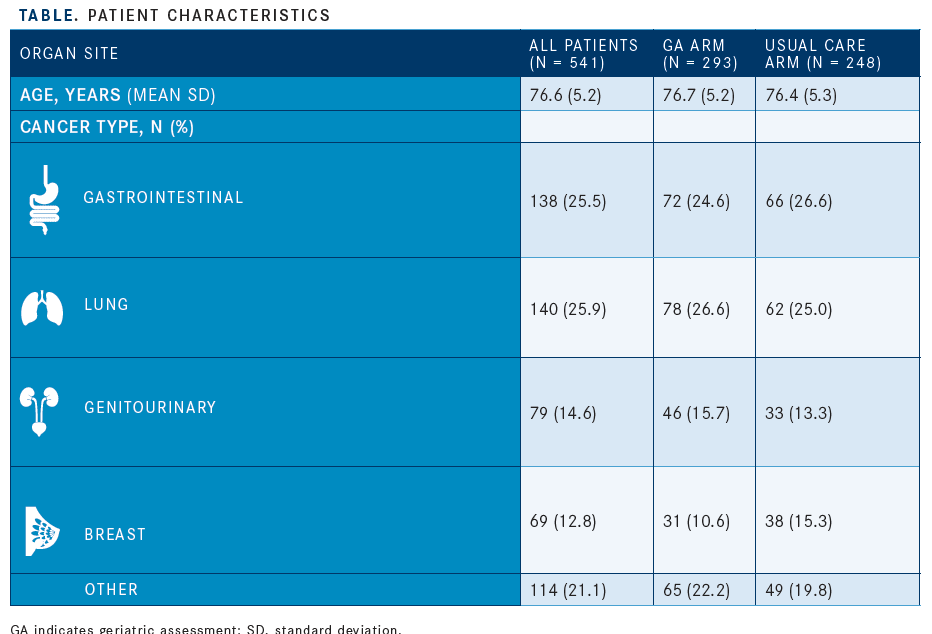

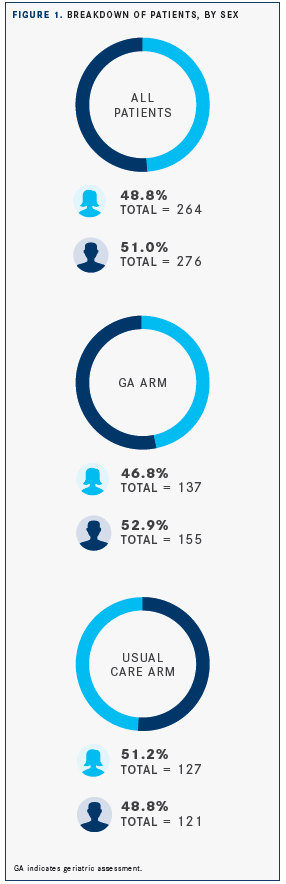

In the study, patients had a mean age of 76.6 years, 276 (51.0%) participants were men, and the most common types of cancer were gas­trointestinal and lung (combined, 278 [51.4%]) (TABLE, FIGURE 1).

Patients in the intervention group reported being more satisfied with communication about aging-related concerns during their visit with an oncologist (difference in mean score, 1.09 points; 95% CI, 0.05-2.13;P= .04). This satisfaction with the level of communication persisted for more than 6 months (difference in mean, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.04-2.16;P= .04). Compared with the usual care arm, patients in the intervention arm also reported having more conversations with the oncologist that focused on aging-related concerns (differ­ence, 3.59; 95% CI, 2.22-4.95;P<.001), and caregivers in the intervention group were more satisfied with communication after the visit (difference, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.12-1.98;P= .03).

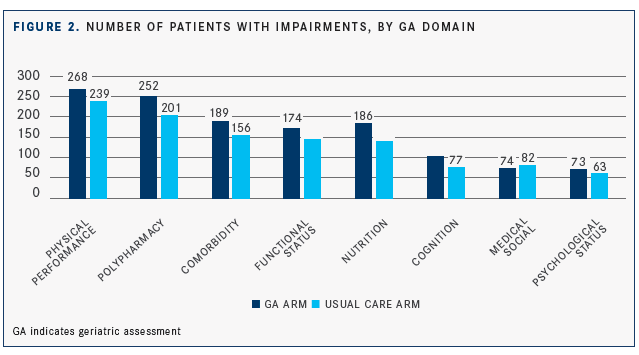

The GA used in the study evaluated 8 domains: functional status, physical performance, morbidity, polypharmacy, cognition, nutrition, psychological health, and social support. These domains are val­ued by older patients, and their assessment can influence clinical decision making.2,3 Impairment in any of these domains could be associated with chemotherapy toxic effects, lower treatment completion, functional decline, early mortality, and higher health­care use, according to the investigators.

Impairments in the physical performance, functional status, and cognition domains were reported by 268, 174, and 103 patients, respectively, in the GA arm and by 239, 145, and 77 patients in the usual care arm (FIGURE 2).

Mohile and colleagues reported an over­all adjusted mean number of conversations about age-related concerns during the oncology visit of 6.34 (range, 0-18), with an adjusted mean of 8.02 conversations in the intervention group compared with 4.43 in the usual care arm (difference, 3.59; 95% CI, 2.22-4.95;P<.001).

In the usual care arm, which did not include a personalized summary for each patient, “if the patient exhibited signs of depression or cognitive impairment, we alerted the oncologist for ethical reasons,” said Mohile. “But it wasn’t the same level of detail in terms of a summary of aging-related conditions and recommendations that was given to the intervention group.”

Mohile described an example of a patient who had a recent issue with falling. Older patients who fall are at higher risk of chemo­therapy toxicity, said Mohile.4“We alert the oncologist that the patient has had a recent fall, and after shared decision making with the patient, suggest a home safety evalua­tion physical or occupational therapy, and provide handouts for fall risk prevention.”

The benefits of GA are widely acknowledged by oncologists, said Mohile, “but the challenge is that it is not reimbursed. Although time codes can be billed, there is no official code for the assessment, presenting a challenge when billing,” she said. Despite these challenges, Mohile believes the “GA is helpful, valuable, and [something that] patients care about. We need to make a greater effort to advocate for its implementation.”

References

- Mohile SG, Epstein RM, Hurria A, et al. Communication with older patients with cancer using geriatric assessment: a cluster-random­ized clinical trial from the National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program [Published online November 7, 2019].JAMA Oncol. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.4728.

- Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients.N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1061-1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528.

- Mohile SG, Magnuson A, Pandya C, et al. Community oncologists’ decision-making for treatment of older patients with cancer.J Natl Compr Canc Netw.2018;16(3):301-309. doi: 10.6004/ jnccn.2017.7047.

- Magnuson A, Sattar S, Nightingale G, Saracino R, Skonecki E, Trevino KM. A practical guide to geriatric syndromes in older adults with cancer: a focus on falls, cognition, polypharmacy, and depression.Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book.2019;39:e96-e109. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_237641.

2 Commerce Drive

Cranbury, NJ 08512

All rights reserved.