The Role of Macrophages in BRAF Inhibitor Resistance

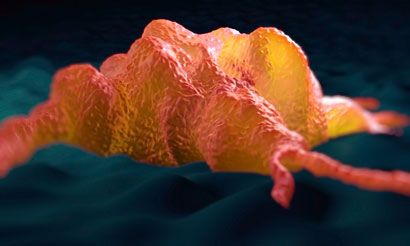

Turning their experimental focus on the tumor microenvironment, the authors of a paper published in Clinical Cancer Research have shed light on the role of melanoma-associated tumor macrophages in resistance to BRAF V600E inhibitors.

Turning their experimental focus on the tumor microenvironment, the authors of a paper published in Clinical Cancer Research have shed light on the role of melanoma-associated tumor macrophages in resistance to BRAF V600E inhibitors.

Turning their experimental focus on the tumor microenvironment, the authors of a paper published inClinical Cancer Researchhave shed light on the role of melanoma-associated tumor macrophages in resistance to BRAF V600E inhibitors.1

According to the study authors, although vemurafenib and dabrafenib are both approved for unresectable or metastatic melanoma withBRAF V600Emutation and have improved overall survival,2,3many patients relapse. New mutations leading to reactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by a variety of mechanisms, includingBRAFamplification andNRASmutation, may explain acquired resistance.1However, the authors point to evidence that the number of macrophages in the melanoma microenvironment, as well as the concentrations of macrophage-produced factors, inversely correlate with patient outcome in early- and late-stage melanoma.4-6

Speaking of their decision to conduct research on the role of melanoma-associated macrophages, Russel E. Kaufman, MD, president emeritus of the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia and lead author of the study, said, “The paradox has been that many cancers are intensely infiltrated with macrophages that do not kill the cancer. In fact, some studies have indicated a worse prognosis if macrophages are present.” Referring to previous influential studies by his group, he continued, “Recently we discovered that monocytes and macrophages have a receptor for a ligand, SECTM1.7We also discovered that SECTM1 is a chemoattractant for monocytes through the SECTM1 receptor CD7. Furthermore, melanomas may express high levels of SECTM1.”

Summing up the direction of the research, Kaufman added, “We then recognized that melanomas sometimes increase the macrophage infiltration following BRAF-targeted therapy, so we set out to determine if this contributed to relapse from BRAF-inhibitor therapy and, if so, the mechanism.”

In a comprehensive approach, Kaufman et al used cell co-culture, proliferation, and cell death assays, conducted animal studies, and finally analyzed data from patients with melanoma treated with a BRAF inhibitor (BRAFi). The team used a model system employing transwell co-culture of melanoma cells and human macrophages.

“In an earlier study, we developed a method to produce macrophages from normal human monocytes, and they [the macrophages] behaved like tumor-associated macrophages in several experimental systems,” explained Kaufman. “Thus, we had an abundant source of macrophages. In addition, we work in a melanoma research center that has many experimental animal model systems that we can use.”8

Macrophages and Resistance to BRAF Inhibition

Kaufman et al found that, when cultured alone with the BRAFi PLX4720 (an analogue of vemurafenib), the mutantBRAF V600Emelanoma cell lines were impacted by its pharmacological activity. However, if they were co-cultured with the macrophages, each cell line became resistant, and increased proliferation was detected by the WST-1 proliferation assay. Further analysis showed that there were fewer necrotic and apoptotic melanoma cells when macrophages were present during BRAFi treatment. This led the team to believe that certain factor or factors must be released by macrophages and responsible for the subsequent development of resistance to the drug by the activation of alternative pathways in melanoma cells.

Pathways and the Soluble Growth Factors

Escape from BRAF inhibition can be achieved by a variety of mechanisms, so in the next stage of their experiments, the researchers sought to analyze whether macrophages contribute to the activation of alternative signaling pathways in melanoma cells in the presence of a BRAFi. They found a strong increase in the phosphorylation of ERK when macrophages were added to the co-culture system after 6 hours of treatment with PLX4720. Curiously, although reactivation of the MAPK pathway was still evident after 18 hours of co-culture, no changes were seen in other well-recognized melanoma survival components (AKT, NF-kß, CRAF, and ARAF), nor did macrophages appear to activate STAT3 signaling or upregulate the expression of PDGFRß expression in the presence of the drug. Also, because of the short time to activation of MAP, the authors ruled out genetic changes in the melanoma cells.

MEK1 and MEK2 siRNA were used next to block the activation of MAPK at the point of ERK signaling. As expected, this maneuver reduced the effects of macrophages on the melanoma cells in the presence of PLX4270. However, it did not completely abolish it, suggesting that other mechanisms may be involved.

Identifying the Soluble Growth Factor

It is well known that many soluble growth factors can permit escape from BRAFi-induced inhibition of cell growth. This study tested a variety of options in the co-culture system (Table 1).

Table 1. Escape From BRAFi-induced inhibition of cell growth by co-culture system options

Growth Factor Pathway Inhibited

Inhibitor

Impact on Macrophage-Mediated Effects

EGF

Gefitinib

No

HGF

AMG208

No

FGF2

PD173074

No

EGF indicates epidermal growth factor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor 2.

Inhibition of these key escape pathways was without impact on the macrophage-mediated growth-promoting effects on melanoma cells, so the authors used a Luminex assay to analyze the soluble growth factors produced by the macrophages and then determined which would rescue melanoma cells from BRAFi-induced growth inhibition and cell death (Table 2).

Table 2. Rescue From BRAFi-Induced Growth Inhibition and Cell Death in Luminex Assay

Growth Factor

Rescue From BRAFi Effects

VEGF

Yes

CXCL1

No

EGF

No

IL8

No

M-CSF

No

TNFα

No

PDGF

No

CXCL1 indicates chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1; EGF, epidermal growth factor; IL8, interleukin 8 ; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor ;TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α ; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

The authors found that only vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) activated the MAPK pathway in melanoma cells, but not to the same extent as that occurring in melanoma cells co-cultured with macrophages in the presence of PLX4720. They did not rule out that the other growth factors may act in concert with VEGF to impact tumor growth. Commenting on whether or not the researchers initially suspected VEGF would be so involved, Kaufman said, “We did not. We found VEGF through a screening discovery process looking at gene expression.”

VEGF and Melanoma

The role of VEGF in angiogenesis is well established, as is its role in melanoma cell growth and survival.1,9The authors found that the melanoma cell lines expressed VEGF receptors 1, 2, and 3, neuropilin-1, and the co-receptor integrin-ß3, but the macrophages had no effect on their expression. Blocking these receptors with lenvatinib, or brivanib alaninate (blockers of all 3 VEGF receptors), reduced the macrophage-induced melanoma cell protective effects and blocked the macrophage-induced reactivation of signaling in the ERK pathway. In a final step, the authors used anti-VEGF monoclonal antibodies to block VEGF signaling, because lenvatinib and brivanib alaninate target other tyrosine kinases.

The macrophage-mediated BRAFi resistance was significantly reversed by this treatment, confirming that VEGF plays a pivotal role in macrophage-mediated BRAFi resistance.

BRAFi and the Macrophages

Once the team had established that VEGF was the mediator, experiments were conducted to determine how BRAFi caused the macrophages to produce and release VEGF. The team found that the MAPK pathway was strongly activated in macrophages in as little as 30 minutes following treatment with PLX4270. Furthermore, RAS activity in macrophages was found to be 2- to 4-fold higher than inBRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines. The authors concluded that BRAF inhibition activates the MAPK pathway because of this high level of endogenous RAS activity; BRAF inhibition increased macrophage growth and reduced the incidence of cell death. In support of these experimental observations, examination of tumor samples from 10 patients with melanoma identified a higher proportion of macrophages present after (compared with before) treatment with a BRAFi.

The activation of the MAPK pathway leads to the production of VEGF in macrophages,10and subsequent experiments demonstrated that treatment of macrophages with PLX4270 increased the production of VEGF.

Animal and Patient Data Supporting a Role for Macrophages

Using a murine syngeneic tumor system treated with PLX4720, the authors demonstrated that GW2580, previously shown to reverse macrophage-mediated resistance to BRAFi treatment, could significantly reduce tumor size. However, the effect was less than that achieved using PLX4720. Administering both agents achieved greater reduction in tumor size and weight. GW2580 likely inhibits the macrophages, because treatment of melanoma cell cultures with GW2580 alone had no effect on growth or rate of cell death.

To determine possible clinical relevance of the data, the authors obtained pretreatment stage IV melanoma tissues from 10 patients undergoing therapy with a BRAFi. The tissues were co-stained for the proliferation marker Ki67 and a macrophage marker. Not surprisingly, the macrophages were found to be present in a large number, and Ki67- positive melanoma cells were commonly found to be surrounded by the macrophages, ensuring a microenvironment that would enable rapid tumor growth. An association was found between the number of macrophages present before treatment and progression-free survival. Cox regression analysis showed that a higher number of macrophages pretreatment was associated with shorter progression-free survival (HR, 1.38;P= .046).

Clinical Implications and Future Research

“This study gives us important insight into the off-target effects these inhibitors can have on patients,” Kaufman said. “With this piece of information, we have determined just how important one of these off-target effects can be, and from here, we can decide whether the right approach is to target the macrophages themselves or to design new BRAF-inhibiting drugs that do not activate macrophages.”11

Speaking more generally of the implications of the study, Kaufman added, “We believe there will be many off-targets or paradoxical effects from intended targets. Therefore, the development of new targeted therapies should at a minimum include gene array analysis of cells or cell lines different than the intended targeted cells.”

References

- Wang T, Xiao M, Ge Y, et al. BRAF inhibition stimulates melanoma-associated macrophages to drive tumor growth.Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(7):1652-1664.

- Zelboraf [product information]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA, Inc. www.gene.com/download/pdf/zelboraf_prescribing.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2015.

- Tafinlar [product information]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014.

- Gazzaniga S, Bravo AI, Guglielmotti A, et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages and inhibition of MCP-1 reduce angiogenesis and tumor growth in a human melanoma xenograft.J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(8):2031-2041.

- Jensen TO, Schmidt H, Moller HJ, et al. Macrophage markers in serum and tumor have prognostic impact in American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I/II melanoma.J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(20):3330-3337.

- Torisu H, Ono M, Kiryu H, et al. Macrophage infiltration correlates with tumor stage and angiogenesis in human malignant melanoma: possible involvement of TNFα and IL-1α.Int J Cancer. 2000;85(2):182-188.

- Wang T, Ge Y, Xiao M, et al. SECTM1 produced by tumor cells attracts human monocytes via CD7-mediated activation of the PI3K pathway.J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(4):1108-1118.

- Wang T, Ge Y, Xiao M, et al. Melanoma-derived conditioned media efficiently induce the differentiation of monocytes to macrophages that display a highly invasive gene signature.Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25(4):493-505.

- Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis.N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):2039-2049.

- Kiriakidis S, Andreakos E, Monaco C, Foxwell B, Feldmann M, Paleolog E. VEGF expression in human macrophages is NF-kappaB-dependent: studies using adenoviruses expressing the endogenous NF-kappaB inhibitor IkappaBalpha and a kinase-defective form of the IkappaB kinase 2.J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 4):665-674.

- Wistar Institute. Macrophages may play critical role in melanoma resistance to BRAF inhibitors. www.wistar.org/news-and-media/press-releases/macrophages-may-play-critical-role-melanoma-resistance-braf-inhibitor. Accessed April 13, 2015.

<<<

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More