Preventing and Treating Bone Metastases in mCRPC

Bone metastases in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) can invade a range of sites in the skeleton where they precipitate a spectrum of pathological processes that increase morbidity, negatively affect quality of life, and decrease survival.

1

Bone metastases appear most commonly in the ribs, the spine (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebrae, and pelvis), and have also been documented in long bones (femur).2Metastatic growth at these sites gives rise to severe bone pain, often requiring powerful analgesia and external beam radiation treatment. Spinal cord or nerve root compression, myelosuppression, and disturbances in calcium metabolism also commonly occur.1,3,4

A recent review summarized the pathophysiology of bone pain as, “components of neuropathic, inflammatory and ischemic pain, arising from ectopic sprouting and sensitization of primary afferent sensory nerve fibers within prostate cancer-invaded bones.” It further asserted that metastases arises and is perpetuated by virtue of the cross talk between the osteoclasts and osteoblasts and other factors involved in the bone microenvironment.5 This multifactorial pathophysiology makes it challenging to manage and an imperative to avoid.1

The management of bone pain was explored in a study that included 1305 patients with prostate cancer and bone metastases.6 Overall, 76% of the patients had been treated with bone-targeting agents for a variety of causes, including bone pain (34%), high risk of bone complications (33%), number of bone metastases (12%), locations of bone metastases (8%), and prior history of bone complications (6%). Additionally, 27% of the patients with bone metastases needed opioids for the relief of bone pain.

A recent preclinical study has highlighted an unreported mechanism that promotes the growth of bone metastases in prostate cancer.7Using a mouse model they showed that following injection of prostate cancer cells into the intramedullary cavity of the tibia, tumor growth increased pressure within the mouse tibia. In vitro experiments subsequently revealed that pressure applied to osteocytes facilitated prostate cancer growth and invasion, and this was mediated in part by an upregulation of CLL5 and matrix metalloproteinases in osteocytes.

These findings implicate osteocytes, responding to the increased pressure generated by tumor growth, in the orchestration of the metastatic niche within the bone in patients with prostate cancer.7This again emphasizes the clinical imperative to reduce the incidence of bone metastases in prostate cancer.

Impact of Bone Pain on Survival and Quality of Life

Several studies have assessed the impact of bone pain on survival and quality of life. A retrospective analysis examined 599 patients from three randomized controlled trials conducted from 1992 to 1998.8Patients in this analysis had progressive CRPC adenocarcinoma of the prostate and an ECOG performance status of 0 to 2. The Brief Pain Inventory (validated scale) gauged the impact of pain on selected daily activities and quality of life (QOL).

They found a median pain interference score of 17, and a statistically significant association between pain scores and the risk of death. Comparing men with low (<17) and high (≥17) pain scores, respectively, the median survival times were 17.6 versus 10.2 months (P <.001). When comparing the same two cohorts, median times to bone progression were 6.7 months and 3.8 months, respectively (P <.001).

Men with pain scores ≥17 had a 22% greater risk of bone progression than men with pain scores <17. Median times to PSA progression followed a similar pattern, with 4.0 versus 2.9 months for scores of <17 and ≥17 respectively (P <.001).8

Additionally, a study from 2002,9 found that skeletal-related events (SREs) have clinically meaningful and significant impact on health-related QOL, with physical, emotional, and functional wellbeing all declining after pathologic fractures and radiation therapy. Significant declines in preference and utility scores were noted after fractures and radiation. Pain intensity only declined after radiation treatment, but not after other SREs.

Moreover, another study identified an association between skeletal morbidities and patient reported outcomes and survival.10,11The trial recruited 643 patients, and they received either zoledronic acid or placebo for 15 months. Patients with no SREs at 6 months (landmark) had significantly greater survival at 360 days post landmark (49.7% vs 28.2%; P = .02). Health-related QOL measures in the post landmark period, including pain, were worse in patients who experienced SREs during the landmark period.

Managing Bone Metastases: Bone-Targeted Agents

There are currently a number of treatments that are approved for the management of patients with mCRPC and bone metastases. They include osteoclasttargeting agents, zoledronic acid and denosumab, and radiopharmaceuticals such as ß-particle emitters, strontium-89 chloride and samarium Sm-153 lexidronam, and the α-particle emitter radium-223 (Xofigo).1

Palliative Agents

A phase III trial of zoledronic acid (a bisphosphonate) versus placebo in 643 patients with mCRPC and bone metastases, without severe bone pain, showed that fewer patients taking zoledronic acid dosed at 4 mg every 3 weeks for 15 months experienced SREs versus placebo (33% vs 44% P = .021); however, survival was not significantly different between the groups. At 24 months of follow-up, zoledronic acid treatment reduced the risk of SREs by 36% versus placebo. Bone pain was also reduced in patients treated with zoledronic acid compared with placebo.1,10

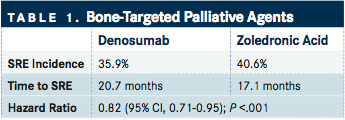

A phase III trial was conducted on denosumab (a monoclonal antibody against a key activator of osteoclastic resorption, RANKL) versus zoledronic acid (TABLE 1).12The primary endpoint was time to first on-study SRE. Overall survival (OS) and investigator-assessed overall disease progression and PSA levels during the study were among key exploratory endpoints.

The study recruited patients with mCRPC and bone metastases who had no prior treatment with bisphosphonates. A total of 1904 patients were randomized, 950 to denosumab and 951 to zoledronic acid. The median time to the first SRE was 20.7 versus 17.1 months for denosumab and zoledronic acid, respectively (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.71-0.95; P = .008). OS and investigator reported disease progression were not significantly different between the groups. Changes in median PSA concentrations and bone pain were also similar between the groups during the study.12

There are a number of toxicity concerns associated with these agents. Nephrotoxicity is a commonly reported adverse event (AE) for bisphosphonates, necessitating monitoring of serum creatinine and appropriate dose adjustment. Denosumab, however, does not cause nephrotoxicity in men with prostate cancer.1

An integrated analysis of three randomized phase III trials (5723 patients) confirmed that both drugs are associated with hypocalcemia and osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ).13 Hypocalcemia incidence was higher among patients treated with denosumab versus zoledronic acid (3.1% vs 1.3% for grade 3/4). ONJ was found to occur more frequently in patients treated with denosumab than zoledronic acid (1.8% vs 1.3%), but the difference was not statistically significant.13

Therapeutic Agents

The status of ß-particle emitters strontium-89 chloride and samarium Sm-153 lexidronam has recently been reviewed by Body et al.1Considering the evidence, they conclude that although both agents seem to exert clinically relevant analgesic effects in patients with bone pain in mCRPC, they have not been unequivocally shown to reduce the incidence of SREs or to extend survival.1

The toxicities associated with these agents are largely hematological, with marrow toxicity being the major side effect of samarium Sm-153 lexidronam. A temporary increase in bone pain during early treatment occurs in 15% of patients treated with strontium-89 chloride.1

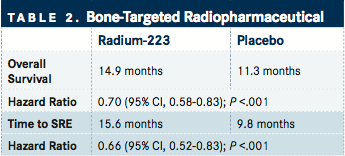

The data for the α-particle emitter radium-223, which selectively binds to areas of increased bone turnover in bone metastases, that secured its approval came from the pivotal phase III ALSYMPCA trial (TABLE 2).14

The study randomized 921 patients in a 2:1 fashion to receive six injections of radium-223 or placebo, one injection given every 4 weeks. The primary endpoint was OS. Secondary endpoints included time to first SRE and biochemical endpoints. The efficacy analysis measured radium-223 survival benefit versus placebo seen at an interim analysis.

The final analysis showed median OS of 14.9 versus 11.3 months for radium-223 and placebo respectively, which represented a 30% reduction in the risk of death for patients treated with radium-223 (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58-0.83; P <.001). Radium-223 treatment significantly prolonged the time to the first SRE (median 15.6 vs 9.8 months; HR 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.83; P <.001). PSA blood levels at week 12 were reduced by ≥30% in 16% of patients in the radium-223 group and in 6% of patients in the placebo group (P <.001). This was maintained for 4 weeks after the last injection in 14% versus 4% of patients in the radium-223 and placebo arms, respectively (P <.001).

Safety profiles were similar between the treatment arms. One patient experienced grade 3 febrile neutropenia in each group. There was one grade 5 hematological event (thrombocytopenia) in the radium-223 group considered possibly related to the study drug.

The incidence of bone pain was reduced in patients treated with radium-223 versus placebo (10% vs 16%). Significantly more patients in the radium-223 group versus placebo experienced a meaningful improvement in QOL as determined by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate score (25 % vs 16%; P = .02).14

PSA and Bone Metastases

Newly approved therapies appear to provide the greatest benefits to patients with asymptomatic metastatic prostate cancer, suggesting that earlier detection of metastases is essential to improving care.15-19A leading question facing the early detection of bone metastases is whether scans should be triggered by a biochemical event or conducted at a fixed interval.

In a study published in 2014, using the SEARCH database, PSA levels, PSA doubling time, and PSA velocity were predictors of metastases in patients with increasing PSA levels after radical prostatectomy.15In the study, data were analyzed from 401 patients undergoing a bone scan for suspected metastatic disease from 1995 to 2012 at six Veteran Affairs Medical Centers. All patients had bone scans, and their PSA levels and PSA kinetics at the time of scan were available. The secondary objective of the study was to use PSA and PSA doubling time (PSA-DT) to rank bone scans according to positivity.

In the study, in patients who were hormone therapy naive, screening for bone metastases should be initiated for a PSA-DT of <9 months. In contrast, there was only a 2% risk of a positive bone scan if the PSA-DT was ≥9 months. A longer PSA-DT was still associated with a very low risk of a positive scan, even in men with high PSA values.

In men after androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), they could not identify a subgroup where the risk of a positive bone scan was low. Even among patients with very low PSA and PSA-DT, the risk of a positive bone scan was ≥10%, and the authors recommended that bone scans should begin early in patients after ADT, even before a PSA level of 5 ng/mL was reached.15

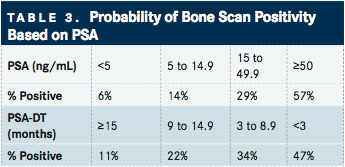

In a more recent analysis, again using the SEARCH database, they devised a tool to assist physicians in the selection of patients with CRPC who may be in need of bone scans. The table combines PSA and PSA-DT, and stratifies patients according to the risk of having a bone scan. They also point out that the table could be used for the identification of particular populations of patients for specific clinical trials (TABLE 3).

This analysis found that men with a PSA of <5, 5 to 14.9, 15 to 49.9, and ≥50 ng/mL had scan positivity of 6%, 14%, 29%, and 57%, respectively (P trend <.001). Scan positivity was 11%, 22%, 34%, and 47% for men with PSADT ≥15, 9 to 14.9, 3 to 8.9, and >3 months, respectively (P trend <.001).16

Future Steps

Considering prostate cancer in general, the extent of the disease dictates the best timing and sequencing of treatments in addition to patient-specific factors. These include the site and extent of disease, speed of progression, symptoms experienced, comorbidities, availability of particular treatments, and contraindications of therapeutic agents/procedures.20With novel bone-directed therapies available, trials are currently assessing the best use of these therapies in combination.

References

- Body JJ, Casimiro S, Costa L. Targeting bone metastases in prostate cancer:Improving clinical outcome.Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12:340-356.

- Wang CY, Wu GY, Shen MJ, et al. Comparison of distribution characteristics of metastatic bone lesions between breast and prostate carcinomas.Oncol Lett. 2013;5:391-397.

- Sartor O, Coleman R, Nilsson S, et al. Effect of radium-223 dichloride on symptomatic skeletal events in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases: results from a phase 3, double-blind, randomised trial.Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:738-746.

- Smith MR, Coleman RE, Klotz L, et al. Denosumab for the prevention of skeletal complications in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: comparison of skeletal-related events and symptomatic skeletal events.Ann Oncol. 2015;26:368-374.

- Muralidharan A, Smith MT. Pathobiology and management of prostate cancer-induced bone pain: recent insights and future treatments.Inflammopharmacology. 2013;21:339-363.

- Body JJ, Henry D, Von Moos R et al. (a) Bone targeting agent (BTA) treatment patterns and the impact of bone metastases (BM) on prostate cancer patients in a real world setting. European Cancer Congress 2015 Vienna abstract # 1527.

- Sottnik JL, Dai J, Zhang H, et al. Tumor-induced pressure in the bone microenvironment causes osteocytes to promote the growth of prostate cancer bone metastases.Cancer Res. 2015;75:2151-2158.

- Halabi S, Vogelzang NJ, Kornblith AB, et al. Pain predicts overall survival in men with metastatic castration-refractory prostate cancer.J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2544-2549.

- Weinfurt KP, Li Y, Castel LD, et al. The significance of skeletalrelated events for the health-related quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer.Ann Oncol. 2005;16:579-584.

- Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. A randomized, placebocontrolled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormonerefractory metastatic prostate carcinoma.J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1458-1468.

- DePuy V, Anstrom KJ, Castel LD, et al. Effects of skeletal morbidities on longitudinal patient-reported outcomes and survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer.Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:869-876.

- Fizazi K, Carducci M, Smith M, et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, doubleblind study.Lancet. 2011;377:813-822.

- Lipton A, Fizazi K, Stopeck AT, et al. Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of 3 pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials.Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3082-3092.

- Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer.N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213-223.

- Moreira DM, Cooperberg MR, Howard LE, et al. Predicting bone scan positivity after biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy in both hormone-naive men and patients receiving androgen-deprivation therapy: results from the SEARCH database.Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17:91-96.

- Moreira DM, Howard LE, Sourbeer KN, et al. Predicting bone scan positivity in non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. doi: 10.1038/ pcan.2015.25.

- Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411-422.

- Basch E, Autio K, Ryan CJ, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus prednisone alone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: patientreported outcome results of a randomised phase 3 trial.Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1193-1199.

- Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy.N Engl J Med. 2014;371:424-433.

- Ryan CJ, Saylor PJ, Everly JJ, et al. Bone-targeting radiopharmaceuticals for the treatment of bone-metastatic castrationresistant prostate cancer: exploring the implications of new data.Oncologist. 2014;19:1012-1018.