Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy Expands Its Reach in Metastatic Melanoma

A number of novel immunotherapies, such as PD-1 inhibitors and targeted drug therapies with BRAF and MEK inhibitors, have become available for managing advanced melanoma.

Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD

Professor of Medicine, Surgery, and Molecular and Medical Pharmacology Director Tumor Immunology Program

Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center

Director

UCLA Los Angeles, CA

With the emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors, targeted therapies, and other novel therapies, the outlook for malignant melanoma has undergone a drastic change from a few years ago. However, a significant portion of patients with stage III or IV melanoma who have undergone surgical resection remain at high risk for relapse.

A number of novel immunotherapies, such as PD-1 inhibitors and targeted drug therapies with BRAF and MEK inhibitors, have become available for managing advanced melanoma.1 Three randomized trials demonstrated that adjuvant therapy with a PD-1 inhibitor (pembrolizumab [Keytruda] or nivolumab [Opdivo]) was clinically beneficial for patients with resected high-risk melanoma compared with standard of care.2-4 At the moment, there is increasing interest in neoadjuvant immunotherapy for high-risk resectable melanoma due to recent reports showing significant efficacy.

“The majority of cancer-specific immune system cells are removed with surgical resection of a localized melanoma,” Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, one of the authors of a report5 on findings from the SWOG S1801 (NCT03698019) trial, said in an interview with Targeted Therapies in Oncology. Ribas is professor of medicine, surgery, and molecular and medical pharmacology, and director of the Tumor Immunology Program at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCLA in Los Angeles, California. “The hypothesis with the SWOG trial was to turn on the immune system with 3 doses of neoadjuvant immunotherapy. [Results from] the study showed a big improvement by giving neoadjuvant immunotherapy before surgery,” Ribas said.

Michael B. Atkins, MD

Deputy Director

Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center

Scholl Professor and Vice Chair

Department of Medical Oncology Georgetown University Medical Center

Melanoma Center at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital and

Melanoma Research Program

MedStar Georgetown Cancer Institute

Washington, DC

According to results from the phase 2, multicenter, open-label SWOG Cancer Research Network S1801 trial recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Sapna P. Patel, MD, and colleagues found that neoadjuvant plus adjuvant pembrolizumab resulted in a significant improvement in event-free survival compared with adjuvant pembrolizumab alone in patients with stage IIIB to IV melanoma.5

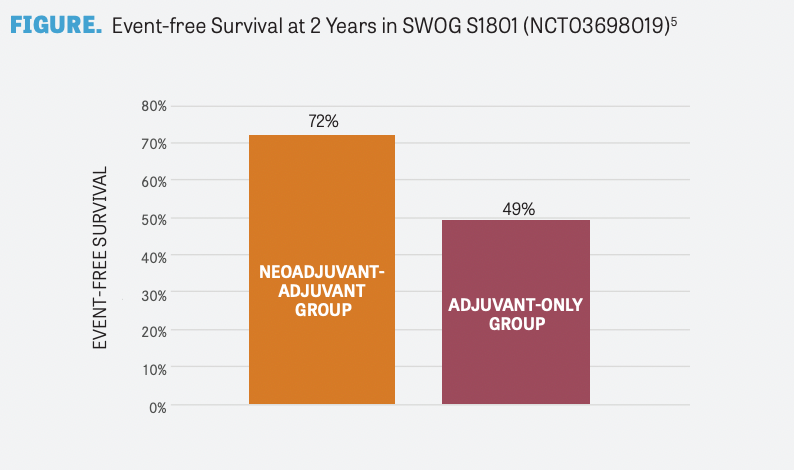

The SWOG S1801 trial randomly assigned 313 patients with resectable stage III or oligometastatic resectable stage IV melanoma to receive neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab (n = 154) or adjuvant pembrolizumab alone (n = 159). At a median follow-up of 14.7 months, event-free survival was significantly longer in the neoadjuvant-adjuvant group compared with the adjuvant-only group (P = .004). Moreover, the 2-year event-free survival rate was numerically higher in the neoadjuvant-adjuvant group compared with the adjuvant-only group (72% vs 49%, respectively; FIGURE5 ). Moreover, death occurred in 14 patients (9%) in the neoadjuvantadjuvant group and 22 patients (14%) in the adjuvant-only group.

The authors concluded, “Among patients with resectable stage III or IV melanoma, event-free survival was significantly longer among those who received pembrolizumab both before and after surgery than among those who received adjuvant pembrolizumab alone. No new toxic effects were identified.”5

“The majority of prior neoadjuvant clinical trials in melanoma were single-arm trials with targeted therapies, immunotherapies. However, these trials did not compare neoadjuvant therapy against standard of care. This is the first clinical trial to formally evaluate neoadjuvant vs adjuvant immunotherapy. I hope the results of the SWOG trial will change the standard of care and improve patient outcomes moving forward,” Ribas added.

BRAF/MEK–Targeted Therapy

Nearly half of patients with melanoma harbor the BRAF V600E mutation. In the past few years, BRAF inhibitors have been approved by the FDA for adjuvant treatment of patients with melanoma with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.6 In the phase 3 COMBI-AD trial (NCT01682083), 870 patients with resected stage III melanoma with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or adjuvant BRAF/MEK–targeted therapy with dabrafenib (Tafinlar) plus trametinib (Mekinist). The primary end point was relapse-free survival. At a median follow-up of 2.8 years, the combination therapy demonstrated a significantly longer duration of survival without relapse or distant metastasis compared with the placebo group.7

Five-year analysis data from the COMBI-AD trial were reported at a median follow-up of 60 months for dabrafenib plus trametinib and 58 months for placebo. In the dabrafenib plus trametinib group, 52% of patients were alive without relapse compared with 36% in the placebo group (HR for relapse or death, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.42- 0.61). Additionally, the dabrafenib plus trametinib group had a higher percentage of patients who were alive without distant metastasis (65% vs 54%, respectively; HR for distant metastasis or death, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.44-0.70).8

Some patients with stage III and IV melanoma experience a recurrence with existing standard-ofcare surgery and adjuvant therapy.

Neoadjuvant targeted therapy with the BRAF/ MEK inhibitors dabrafenib and trametinib in patients with high-risk, histologically or cytologically confirmed, resectable, clinical stage III or oligometastatic stage IV BRAF V600E– or V600K– mutated melanoma was evaluated in a phase 2, single-center, open-label, randomized trial (NCT02231775). Dabrafenib and trametinib block different growth-promoting signals in tumor cells that are activated by the BRAF V600E mutation. The primary end point was event-free survival at 12 months in the intent-to-treat population. The trial was stopped early after a prespecified interim safety analysis revealed significantly longer event-free survival with neoadjuvant plus adjuvant dabrafenib and trametinib than with standard of care.

At a median-follow-up of 18.6 months, 10 of 14 patients in the neoadjuvant plus adjuvant dabrafenib and trametinib group were alive without disease progression compared with 0 of 7 patients in the standard-of-care group. The median event-free survival was 19.7 months vs 2.9 months, respectively (HR, 0.016; 95% CI, 0.00012-0.14; P < .00019).9

Neo Combi was another phase 2 trial (NCT01972347) that evaluated the role of neoadjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with histologically confirmed, resectable, RECIST-measurable, clinical stage III BRAF V600–mutated melanoma. The single-center, single-arm, open-label study evaluated 35 eligible patients who received neoadjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib and underwent resection. At resection, 30 patients (86%) achieved a RECIST response, 16 (46%) had a complete response, 14 (40%) had a partial response, and 5 (14%) had stable disease. After resection and pathological evaluation, all 35 patients achieved a pathological response; 17 of them (49%) had a complete pathological response and the remaining 18 (51%) had a noncomplete pathological response. The authors concluded that “neoadjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib therapy could be considered in the management of RECIST-measurable resectable stage III melanoma as it led to a high proportion of patients achieving a complete response according to RECIST and a high proportion of patients achieving a complete pathological response, with no progression during neoadjuvant therapy.”10

PD-1–Based Immunotherapy

Ipilimumab (Yervoy), a monoclonal antibody targeting CTLA-4, was approved in 2011 as a treatment for patients with metastatic melanoma that improved survival.11,12 This was followed by PD-1 inhibitors such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, which showed similar efficacy to ipilimumab but less toxicity.2,13,14

In advanced disease, the combination of ipilimumab plus nivolumab was superior to either ipilimumab or nivolumab monotherapy. This combination was evaluated in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings by Blank et al.15 The phase 1b OpACIN trial (NCT02437279) randomly assigned 20 patients with palpable stage III melanoma to receive ipilimumab 3 mg/kg and nivolumab 1 mg/kg either after surgery (adjuvant arm) or before and after surgery (neoadjuvant arm). The authors reported that 78% of patients in the neoadjuvant arm achieved a pathological response, with no relapses reported at the median follow-up at 25.6 months. However, 9 of 10 patients in both arms experienced 1 or more grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs). Results from the study demonstrated that neoadjuvant therapy produced superior expansion of tumor-resident T-cell clones compared with the adjuvant arm. The high toxicity rates seen in both treatment arms, however, were concerning.15

The phase 2, multicenter, open-label, randomized OpACIN-neo trial (NCT02977052) aimed to address the issue of toxicity with neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab by identifying the optimal dosing schedule. Eligible patients with resectable stage III melanoma involving only the lymph nodes were randomly assigned into 3 arms: Group A (n = 30) received ipilimumab 3 mg/kg plus nivolumab 1 mg/kg for 2 cycles every 3 weeks; group B (n = 30) received ipilimumab 1 mg/kg plus nivolumab 3 mg/kg for 2 cycles every 3 weeks; and group C (n = 26) received ipilimumab 3 mg/kg for 2 cycles every 3 weeks, then nivolumab 3 mg/kg for 2 cycles every 2 weeks.

The primary end points were the percentage of patients with grade 3/4 immunerelated AEs within the first 12 weeks and the percentage of patients who achieved a radiological objective response and pathological response at 6 weeks. Within the first 12 weeks, grade 3/4 immune-related AEs were seen in 40% of patients in group A, 20% in group B, and 50% in group C. The differences in toxicity between groups B and A and between groups C and A were not statistically significant. The radiological objective response and pathological response rates were 63% and 80%, 57% and 77%, and 35% and 65% in groups A, B, and C, respectively. The authors concluded that the optimal neoadjuvant dosing schedule to minimize toxicity while inducing a pathological response was the group B regimen: ipilimumab 1 mg/ kg plus nivolumab 3 mg/kg for 2 cycles.16

A phase 2 study (NCT02519322) compared neoadjuvant nivolumab monotherapy (n = 12) vs combined neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab (n = 11) in 23 patients with high-risk resectable melanoma. Similar to the OpACIN study,15 the combination of ipilimumab plus nivolumab achieved high response rates, with a RECIST overall response rate (ORR) of 73% (n = 8/11) and pathologic complete response (pCR) rate of 45% (n = 5/11), with 73% of patients (n = 8/11) experiencing grade 3 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). On the other hand, nivolumab monotherapy yielded a modest response, with an ORR of 25% (n = 3/12) and a pCR rate of 25% (n = 3/12); there were grade 3 TRAEs in 8% of patients (n = 1/12). Notably, all 11 patients in the combination arm remained alive after a median follow-up of 15.6 months, which was higher than expected compared with historical controls in this patient population with high-risk disease. Furthermore, compared with nonresponding patients, responding patients had higher CD8-positive T-cell infiltrate, tumor cell PD-L1 expression, and lymphoid marker expression. The authors also observed a difference in clonality in responders between the 2 treatment groups. T-cell infiltrate was more clonal and diverse in responders in the nivolumab monotherapy group.17

Clinical responses to immune checkpoint blockade can be observed rapidly.18 Additionally, a pharmacodynamic response can be detected by blood after a single dose.19 A phase 1b clinical trial (NCT02434354 ) of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab in stage IIIB/C or IV melanoma evaluated the early pharmacodynamic effects of anti–PD-1 therapy in the tumor microenvironment. The study evaluated 27 patients who underwent baseline biopsy prior to receiving a single neoadjuvant dose of pembrolizumab 200 mg. Resection and histological assessment 3 weeks later revealed that 8 patients (29.6%) had a complete or major pathologic response. Of note, this result of 29.6% after 1 dose of pembrolizumab is similar to a result in the phase 2 study (NCT02519322)18 that observed a pCR rate of 25%. Additionally, all patients with early complete or major pathological responses remained alive and disease free at 24 months. In contrast, patients without a robust pathological response at surgery experienced a poor prognosis, with a more than 50% risk of recurrence.20

Targeted-Immunotherapy Combination Trials

Preclinical models suggest that combining BRAF and MEK inhibitors with PD-1 blockade therapy improves antitumor activity.21,22 One model observed an increase in antitumor activity with combined short-term BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapy with murine anti–PD-1 blockade.22

To explore the antitumor activity and safety of triple therapy with dabrafenib, trametinib, and pembrolizumab in patients with BRAF V600–mutated melanoma, the phase 1 KEYNOTE-022 trial (NCT02130466) enrolled 15 patients to receive the combination of approved doses of dabrafenib and trametinib with pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg. Of those 15 patients, 11 (73%; 95% CI, 45%-92%) had an objective response and 6 (40%; 95% CI, 16%- 68%) continued with a response at the median follow-up of 27 months. Eleven patients (73%) experienced grade 3/4 TRAEs, most of which resolved with drug interruption or discontinuation of either the dabrafenib and trametinib combination or pembrolizumab.23

In the phase 3 DREAMseq trial (ECOGACRIN EA6134; NCT02224781), 265 patients with treatment-naïve BRAF V600–mutated melanoma were randomly assigned to receive combination nivolumab/ipilimumab (arm A) or dabrafenib/trametinib (arm B) in step 1.

In step 2, 73 of these patients were randomly assigned to receive dabrafenib/trametinib (arm C) or nivolumab/ipilimumab (arm D) at disease progression. Patients in arm A had improved 2-year overall survival (the primary end point) compared with patients in arm B (71.8% vs 51.5%, respectively; P = .010).24

Conclusions and Implications for Practice

Management of melanoma has evolved significantly, with findings from landmark trials changing recommended clinical practice guidelines. In an interview with Targeted Therapies in Oncology, Michael B. Atkins, MD, deputy director of the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center and William M. Scholl Professor of Oncology at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, DC, said, “In the 1990s, the initial treatment efforts in advanced or stage IV metastatic melanoma were with highdose IL-2 that had response rates of 15% to 16% but durable responses in 7% to 10% of the total patient population. It was proof of principle that the immune system can produce durable remissions in a small subset of patients. After decades of largely unsuccessful attempts to optimize response and minimize toxicity, the efforts then switched to checkpoint inhibitors and BRAF/MEK inhibitors. Just earlier this year, [results from] the phase 3 DREAMseq [NCT02224781] trial determined the preferred sequence of immunotherapy and BRAF-targeted therapy in patients with advanced melanoma containing BRAF mutations. [Results from] the study showed that the sequence involving initial treatment with nivolumab plus ipilimumab resulted in a 20% improvement in 2-year overall survival compared with the sequence beginning with BRAF-targeted therapy [72% vs 52%, respectively]. This result changed the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for frontline treatment for this patient population.”24

Atkins added that in pursuing the optimal dosing regimen, “it is important to appreciate that most toxicity from immunotherapy is short lived, representing 4 to 8 weeks of the total time that patients are on immunosuppressive therapy. However, it is also important to note that in many studies, toxicity is associated with efficacy; therefore, one can consider toxicity more of an end point, which is evidence that the immune system has been activated, which is the goal of the therapy. Once activated, it is hoped that the immune system will recognize the melanoma as the most foreign tissue in the body and be able to destroy it, thus enabling the patient to experience a durable treatment-free remission. To me and most of my patients, a short period of toxicity is worth enduring if it is associated with not only a reduced incidence of death but also the opportunity to stop therapy and return to their precancer lives. We call such patients ‘thrivers’ who, being freed from cancer and cancer therapy, are untethered from their oncologist’s office and able to pursue travel, family events, and life in general with renewed passion.”

Neoadjuvant therapy for advanced melanoma is a rapidly evolving area of clinical research, and the optimal dosing regimen is still to be determined. Use of neoadjuvant immunotherapy is supported by evidence presented in landmark clinical trials such as the SWOG S1801 trial.5 These new developments give clinicians more options to offer patients with advanced disease. More importantly, Ribas added, “Neoadjuvant immunotherapy goes beyond melanoma. In any situation where adjuvant immunotherapy is approved after surgery, it would make sense to explore neoadjuvant therapy in those patients as well.” In agreement with Ribas, Atkins said, “We will see a big impact from the SWOG S1801 trial. The results of this trial will not only influence treatment of patients with melanoma but also those with other cancers that are immune responsive.” In the future, Atkins foresees “development of novel neoadjuvant immunotherapy combinations that involve anti–PD-1 antibodies with other immunotherapy agents, such as LAG-3 inhibitors, oncolytic viruses, and toll-like receptor agonists.”

References

1. Comito F, Pagani R, Grilli G, Sperandi F, Ardizzoni A, Melotti B. Emerging novel therapeutic approaches for treatment of advanced cutaneous melanoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(2):271. doi:10.3390/cancers14020271

2. Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al; CheckMate 238 Collaborators. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1824-1835. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1709030

3. Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1789-1801. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1802357

4. Grossmann KF, Othus M, Patel SP, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus IFNα2b or ipilimumab in resected high-risk melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(3):644-653. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1141

5. Patel SP, Othus M, Chen Y, et al. Neoadjuvant-adjuvant or adjuvant-only pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(9):813-823. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2211437

6. Dabrafenib–trametinib combination approved for solid tumors with BRAF mutations. National Cancer Institute. July 21, 2022. Accessed March 13, 2023. http://bit.ly/3Zqy8a0

7. Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, et al. Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1813-1823. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1708539

8. Dummer R, Hauschild A, Santinami M, et al. Five-year analysis of adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(12):1139-1148. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2005493

9. Amaria RN, Prieto PA, Tetzlaff MT, et al. Neoadjuvant plus adjuvant dabrafenib and trametinib versus standard of care in patients with high-risk, surgically resectable melanoma: a single-centre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(2):181-193. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30015-9

10. Long GV, Saw RPM, Lo S, et al. Neoadjuvant dabrafenib combined with trametinib for resectable, stage IIIB-C, BRAFV600 mutation-positive melanoma (NeoCombi): a single-arm, open-label, single-centre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(7):961-971. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30331-6

11. Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711-723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003466

12. Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(5):522-530. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70122-1

13. D’Angelo SP, Larkin J, Sosman JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab in patients with mucosal melanoma: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(2):226-235. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.67.9258

14. Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):908-918. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00083-2

15. Blank CU, Rozeman EA, Fanchi LF, et al. Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma. Nat Med. 2018;24(11):1655-1661. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0198-0

16. Rozeman EA, Menzies AM, van Akkooi ACJ, et al. Identification of the optimal combination dosing schedule of neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma (OpACIN-neo): a multicentre, phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(7):948-960. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30151-2

17. Amaria RN, Reddy SM, Tawbi HA, et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in high-risk resectable melanoma. Nat Med. 2018;24(11):1649-1654. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0197-1

18. Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, et al. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):298-306. doi:10.1038/nrc3245

19. Huang AC, Postow MA, Orlowski RJ, et al. T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2017;545(7652):60-65. doi:10.1038/nature22079

20. Huang AC, Orlowski RJ, Xu X, et al. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):454-461. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0357-y

21. Moreno BH, Mok S, Comin-Anduix B, Hu-Lieskovan S, Ribas A. Combined treatment with dabrafenib and trametinib with immune-stimulating antibodies for BRAF mutant melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2015;5(7):e1052212. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2015.1052212

22. Deken MA, Gadiot J, Jordanova ES, et al. Targeting the MAPK and PI3K pathways in combination with PD1 blockade in melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(12):e1238557. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2016.1238557

23. Ribas A, Lawrence D, Atkinson V, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition with PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25(6):936-940. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0476-5

24. Atkins MB, Lee SJ, Chmielowski B, et al. Combination dabrafenib and trametinib versus combination nivolumab and ipilimumab for patients with advanced BRAF-mutant melanoma: the DREAMseq trial-ECOG-ACRIN EA6134. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(2):186-197. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.01763

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More