Identifying and Managing Immune-Related Adverse Events

As checkpoint inhibition is increasingly being utilized beyond the scope of clinical trials, it’s essential that community-based oncologists and physicians learn how to quickly diagnose and treat immune-related adverse events.

Randy F. Sweis, MD

Checkpoint inhibition amplifies immune activity, allowing the immune system to detect and destroy cancer cells. But in some patients, this amplification of the immune system causes uncomfortable, and potentially lethal, adverse events (AEs). As checkpoint inhibition is increasingly being utilized beyond the scope of clinical trials, it’s essential that community-based oncologists and physicians learn how to quickly diagnose and treat immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

“If we catch these events early, we can typically manage them very successfully in the vast majority of cases,” said Randy F. Sweis, MD, an instructor of medicine at the University of Chicago Medicine. “When we look historically at events that were severe, or even life threatening, a lot of times those occur in a setting in which there were delayed interventions.”

Red-Flag Symptoms

The AEs of chemotherapy and radiation are so familiar to the general public that most people can rattle them off without hesitation. The possible AEs of checkpoint inhibition are not nearly as well known yet, which can be challenging because the diagnosis and management of irAEs is largely dependent on patient awareness.

“When patients get diagnosed with cancer and are treated with chemotherapy, they often know what to look for. Immunotherapy is very different,” Sweis said. “That’s why patient education may be the most critical component to the appropriate management of adverse events with immunotherapies.”

Currently there are 6 FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors: ipilimumab (Yervoy; antiCTLA-4), nivolumab (Opdivo; anti–PD-1), pembrolizumab (Keytruda; anti–PD-1), atezolizumab (Tecentriq; anti–PD-L1), avelumab (Bavencio; anti–PD-L1), and durvalumab (Imfinzi; anti–PD-L1).

Patients being treated with any of these monoclonal antibodies should be instructed to report the following red-flag symptoms to their medical team immediately:

• Diarrhea (more than 2 loose stools in 24 hours)

• Bloody diarrhea

• Fever greater than 100.5°F

• Profound fatigue

• Production of yellow or green sputum

• Shortness of breath

• Skin rash

These symptoms are the most obvious manifestations of 3 of the most common irAEs: colitis, pneumonitis, and dermatologic AEs. However, irAEs can affect any organ system, so patients and families should be instructed to report any symptom that seems unusual.

During the 2017 ESMO Immuno-Oncology Symposium that took place December 7-10 in Geneva, Switzerland, the European Society for Medical Oncology released a guide of immunotherapy AEs for patients, based on the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of toxicities from immunotherapy.1,2The guide stated that in addition to the symptoms mentioned above, patients should also look out for less common symptoms, including headache, confusion, muscle weakness, numbness, painful or swollen joints, tendency to bruise easily, and loss of vision.

“Whenever we start a patient on checkpoint inhibition, I always emphasize that we’d rather hear from you sooner than later,” said Jeffrey Weber, MD, PhD, deputy director of the Perlmutter Cancer Center and co-director of the Melanoma Research Program at NYU Langone Health in New York, New York. “We’d rather hear about something and decide it’s not worth worrying about than not hear from you and let it develop into a full-blown [adverse event].”

Some patients are hesitant to report AEs because they don’t want them to potentially interfere with their cancer treatment. Weber suggests ensuring that patients know that there is absolutely no benefit to “toughing it out.” To underscore the importance of reporting AEs, let patients know that early detection and treatment of irAEs is key to successful management.

Presentation and Incidence of Immune-Related Adverse Events

“I’ve been treating patients with immunotherapy for at least 15 years, and the only treatment-related deaths I’ve ever seen came about because patients elected to wait to let us know [about adverse events],” Weber said. “The quicker you get to it, the better off you’re going to be. Once you let things progress beyond a certain point, you’re truly behind the 8 ball in terms of managing the toxicities.”

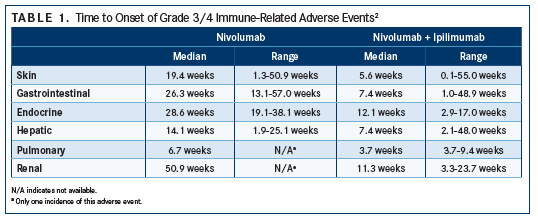

Although the possibility of irAEs exists every time someone is treated with checkpoint inhibition, most patients do quite well. Reactions, if present at all, tend to be lower grade and easily manageable; additionally, most irAEs tend to occur within 3 months of beginning treatment (earlier for skin and pulmonary events and later for renal events) (TABLE 1), but typically do not appear upon initiation.2

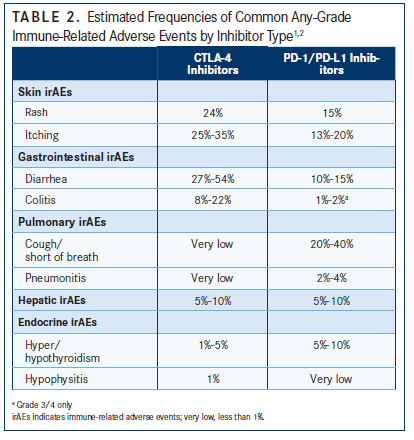

In general, irAEs are more common with CTLA-4 checkpoint inhibition than PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition (TABLE 2). Any-grade irAEs have been documented in 60% to 85% of patients treated with ipilimumab.1 IrAEs are also more likely to occur in patients undergoing combination therapy involving a CTLA-4 inhibitor.

In the CheckMate 067 trial, the incidence of grade 3/4 toxicity (according to National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events3) increased when nivolumab was combined with ipilimumab. The incidence of grade 3/4 irAEs was 59% for combination therapy versus 21% for nivolumab monotherapy and 28% for ipilimumab monotherapy.4

A variety of events can occur, but irAEs tend to hit select organs (FIGURE) more frequently than others:

Respiratory irAEs

Pneumonitis is an uncommon but potentially lethal irAE of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. In a study of 915 patients treated with checkpoint blockade, the overall incidence of pneumonitis was 5%, including 3% of those treated with antiPD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy and 10% of those treated with a combination that included an anti–CTLA-4 antibody5; however, pneumonitis is less common with antiCTLA-4 monotherapy.2The median time to onset was 2.8 months (range, 9 days19.2 months), but onset tended to occur earlier in patients receiving combination therapy (median 2.7 vs 4.6 months).5

Seventy-two percent of the patients with pneumonitis had grade 1/2 toxicity, and 86% of affected patients improved after checkpoint inhibition was withheld or they were treated with immunosuppression. Five patients (0.5% of the total population) died despite treatment. Infectious complications and progression of the cancer appeared to be the cause of death in 4 of those patients.

The most common presenting symptoms of pneumonitis are shortness of breath and cough. However, some patients are asymptomatic. (In the study referenced above, one-third of patients with pneumonitis were asymptomatic.)

Pulmonary toxicity is more common in patients with lung cancer than other cancers. That “could be a reflection of some underlying immune microenvironment,” Sweis said. Or it could be because many patients with lung cancer have a history of smoking and have already undergone lung surgery and radiation, according to Weber.

Gastrointestinal irAEs

Both the liver and the colon can be adversely affected by immunotherapy. Colitis is the most common gastrointestinal irAE, and the most common symptom of colitis is diarrhea. Approximately 10% to 15% of patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibition will develop diarrhea, Sweis said. The incidence rate is higher with CTLA-4 checkpoint blockade, ranging from 27% to 54%.2 Severe diarrhea, representing high-grade toxicity, only occurs in about 1% to 2% of patients on PD-1 monotherapy and in about 10% of patients on combination immunotherapy, Sweis noted.

Hepatitis can occur in 5% to 10% of patients with single-agent checkpoint inhibition and in 25% to 30% of patients treated with a combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab.2 Hepatotoxicity is most often noticed via increases in liver function tests. “It’s relatively unusual to have someone with hepatotoxicity that’s really symptomatic,” Sweis said. “It happens, but it’s not that common."Dermatologic irAEs

Skin irAEs occur in about a quarter to one-third of patients treated with checkpoint inhibition and up to 45% treated with ipilimumab. Most cases are mild and usually occur as either rash, pruritus, or vitiligo, which is mostly seen in patients with melanoma. Grade 3/4 rash has been seen in less than 5% of patients treated with antiPD-1 therapy and in less than 3% treated with anti–CTLA-4 monotherapy.2

“Usually, skin toxicities are pretty low grade, usually grade 1/2. Patients may have a minor rash or little itching. If you ask them, ‘Does it keep you up at night?’ generally the answer is no,” Weber said.

Dermatologic irAEs may appear within the first few weeks of checkpoint inhibition. The average time of onset for skin symptoms in patients treated with ipilimumab is 3.6 weeks compared with 8 to 12 weeks for gastrointestinal or pulmonary symptoms.6

Endocrinopathies

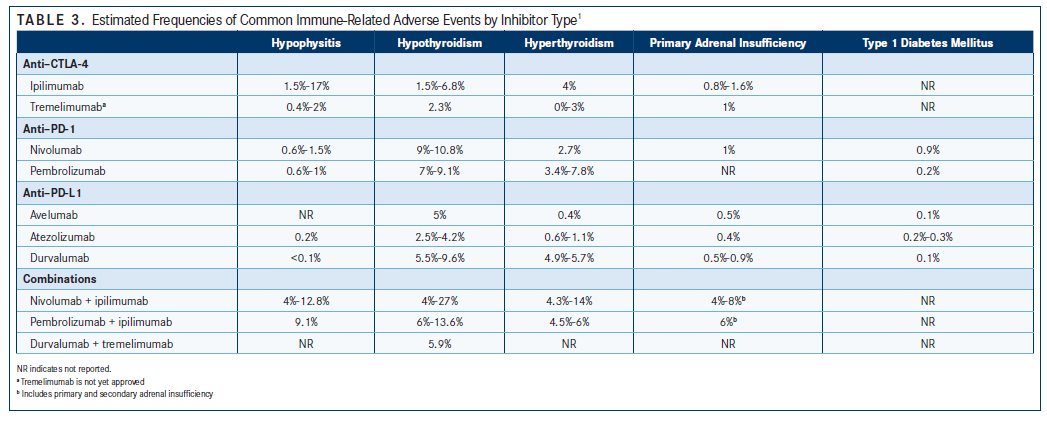

Endocrine system irAEs are also fairly common with checkpoint inhibition; approximately 10% to 15% of patients experience some form of endocrinopathy.7 Hypophysitis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism are the most common endocrinopathies, although type 1 diabetes mellitus and primary adrenal insufficiency have also occurred in patients receiving checkpoint immunotherapy (TABLE 3).

Most endocrinopathies are asymptomatic and caught via routine monitoring of lab work. It’s not yet entirely clear if patients who develop immunotherapy-related endocrine dysfunction will regain full endocrine function when immunotherapy is stopped. “I don’t have a solid answer,” Sweis said. “I’ve seen it recover and think that, more than likely, they’ll recover. But if they don’t, they can typically be managed with medications such as steroid or hormone replacements.”

A reported resolution of hypothyroidism occurred in 20% to 30% of patients who had been treated with an antiPD-1 monoclonal antibody and in up to 75% of patients with hyperthyroidism who had received either nivolumab or pembrolizumab.7

Patients receiving adjuvant checkpoint inhibition “appear to have a slight increase in endocrinopathies versus metastatic patients,” Weber said. “That’s not histology-specific that we know of.”

Potential Causes of Immune-Related Adverse Events

Researchers are still trying to ascertain the underlying cause of irAEs from treatment with checkpoint inhibitors. Some potential mechanisms for these events include an increased level of T-cell activity against antigens that are present in both cancerous and healthy tissue from the immunotherapy. Additionally, there could be a greater amount of preexisting autoantibodies in the microenvironment or of inflammatory cytokines. irAEs could also occur because of enhanced complement-mediated inflammation as a result of direct binding of an antiCTLA-4 antibody with the CTLA-4 that is expressed in normal cells, as in the pituitary gland.8

Clinical Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events

Treatment of irAEs depends on the severity of the reaction. Drug labels for all FDA-approved checkpoint inhibitors contain grading criteria and treatment information. Bristol-Myers Squibb has released a management guide for irAEs from treatment with nivolumab, offering guidance for the symptoms and suggested management for each reaction.9

“For most grade 1 toxicities, you’re going to go ahead and [continue to] treat,” Weber said. Checkpoint immunotherapy can continue, but under careful observation. If the AE is uncomfortablesay, an itchy skin rash—symptomatic treatment may be appropriate. OTC medications, such as diphenhydramine and camphor/pramoxine/zinc can be used to treat grade 1 skin reactions.

Checkpoint inhibition should be held when irAEs of grade 2 or higher occur. The length of time to withhold immunotherapy depends on the patient’s response. Generally, checkpoint immunotherapy should not be resumed until symptoms or toxicity are grade 1 or less.2

If symptoms continue or progress despite ceasing immunotherapy, steroid treatment is appropriate. Skin reactions are often treated with topical corticosteroids for grade 3 toxicities or higher. Oral prednisone is usually used to treat other moderate irAEs, with some physicians recommending a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day. Combination topical and oral steroids may be used to treat skin irAEs that don’t respond to or progress despite topical treatment; these can be tapered when symptoms subside to grade 1 or less.

Grade 3/4 toxicities usually require intravenous steroids and hospitalization. Checkpoint inhibition may need to be permanently discontinued.

For grade 3/4 irAEs that do not improve following 2 to 3 days of steroids, additional or alternative immune suppressants may be needed. Infliximab, an immunosuppressive drug that blocks the effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, is one such option. However, it is not recommended in the management of immune-related hepatitis.

“We don’t want to jump too quickly, but if we need to use it, we will,” Sweis said.

Endocrinopathies should be monitored via routine blood draws. “If we see liver functions go up a little bit, we’ll typically delay a dose of immunotherapy,” Weber said. “I may put them off for 2 days just to see what direction they’re going. If they come back and their liver functions are down, we’ll treat them. If the liver functions are up, we’ll hold.”

Hypo- and hyperthyroidism are managed with thyroid medication, or beta-blockers if the patient is symptomatic. “If the thyroid function is a little bit abnormal, that’s okay; we don’t do anything about it. If the thyroid-stimulating hormone rises too high, we supplement that with oral thyroid medication,” Sweis said.

For rarer toxicities, such as neurologic and cardiac toxicities, quick intervention is especially recommended and the use of immunotherapy agents should be suspended until the cause and management of the event are defined for any event above grade 1. For patients who experience myasthenia or Guillain-Barré syndrome, plasmapheresis or intravenous immunoglobulin may be needed.

Appropriate classification and management of irAEs will help patients obtain the maximum net benefit from checkpoint immunotherapy. “You don’t want to be so gun shy that you stop people early on a therapy that would benefit them,” Sweis said. Many patients with grade 1/2 toxicities are able to resume immunotherapy after treatment. “You have to watch them very closely if you’re rechallenging them. Oftentimes, we can get away with it. Either they recover completely or they recover to a grade 1 level and it’s manageable to the patient and not causing any longterm harm, so we can continue,” Sweis said.

Does Treatment for Immune-Related Adverse Events Decrease the Effectiveness of Immunotherapy?

According to available data, halting checkpoint immunotherapy to manage irAEs does not adversely affect a patient’s response to immunotherapy. In an analysis of 576 patients with advanced melanoma who were treated with antiPD-1 antibodies, there was no significant difference in the objective response rate between those who received immunosuppression (29.8%) and those who did not (31.8%).10

Another study’s findings showed that overall survival and time to treatment failure for patients receiving ipilimumab did not differ depending on whether patients experienced an irAE or if they were treated with immunosuppressive therapy for toxicity.11

Remaining Research Questions

To date, it’s not entirely clear if patients with pre-existing autoimmune conditions can safely receive checkpoint immunotherapy. “There’s some emerging data that suggest we can treat patients who have existing autoimmune disease, but that will probably vary depending on what the disease is and how severe it is at baseline,” Sweis said.

Researchers are also looking for biomarkers that could potentially predict the onset of irAEs. Some are exploring whether or not the intestinal microbiota can predict immune toxicity.

The results of these, and future studies, will certainly help clinicians manage irAEs. But today, despite the potential for serious irAEs, the overall AE profile of checkpoint inhibition is far more tolerable and manageable than the typical side effects of chemotherapy.

“I would rather be delivering checkpoint blockade than giving high-dose chemotherapy any day of the week,” Weber said. “Almost all of the [adverse events] of checkpoint inhibition are highly reversible. Virtually all the toxicities of immunotherapy will resolve when you treat them correctly.”

References

- ESMO Patient Guide on Immunotherapy Side Effects. European Society for Medical Oncology website. esmo.org/content/download/124130/2352601/ file/ESMO-Patient-Guide-on-Immunotherapy-Side-Effects.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed January 17, 2018.

- Hannen J, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up.Ann Oncol.2017;28(suppl 4):iv119-iv142. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx225.

- Common terminology criteria for adverse events. National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Treatment & Diagnosis website. ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/ electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_40. Published June 14, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2018.

- Wolchok J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma.N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1345-1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684.

- Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo K, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy.J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(7):709-717. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005.

- Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab.J Clin Oncol.2012;30(21):2691- 2697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750.

- Cukier P, Santini F, Scaranti M, Hoff AO. Endocrine side effects of cancer immunotherapy.Endocr Relat Cancer.2017;24(12):T331-T347. doi: 10.1530/ ERC-17-0358.

- Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellman MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade.N Engl J Med.2018;378(2):158-168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481.

- Opdivo (nivolumab): Immune-Mediated Adverse Reactions Management Guide. Opdivo website. opdivohcp.com/servlet/servlet.FileDownload?file=00Pi000000ijs1vEAA. Accessed January 17, 2018.

- Weber JS, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, et al. Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: a pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma.J Clin Oncol.2017;35(7):785-792. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.1389.

- Horvat TZ, Adel NG, Dang TO, et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.J Clin Oncol.2015;33(28):3193-3198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8448.

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More

2 Commerce Drive

Cranbury, NJ 08512

All rights reserved.