Gergis and Rowley Examine Treatment of Moderate Chronic GVHD

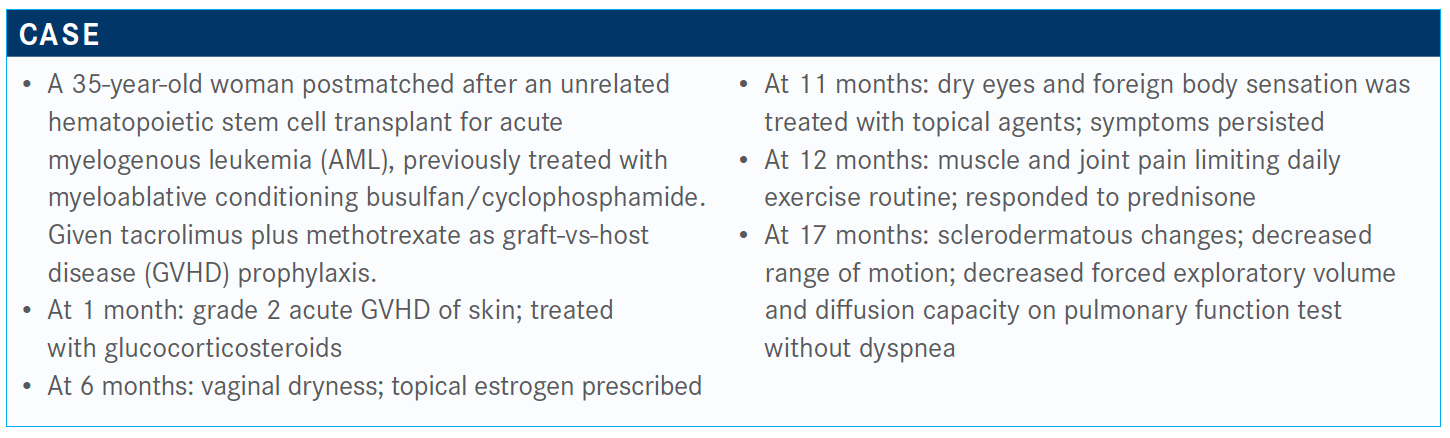

During a Targeted Oncology Case Based Peer Perspective event, Usama Gergis, MD, MBA, and Scott D. Rowley, MD, reviewed the case of a 35-year-old woman with moderate chronic graft-versus-host disease.

Scott D. Rowley, MD

During a Targeted Oncology Case Based Peer Perspective event, Usama Gergis, MD, MBA, professor of Oncology, director of Bone Marrow Transplant and Immune Cellular Therapy, Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, Thomas Jeffereson University Hopsital, and Scott D. Rowley, MD, director of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Services, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Hackensack University Medical Center, reviewed the case of a 35-year-old woman with moderate chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Targeted Oncology™: What is your initial impression of this case?

Usama Gergis, MD, MBA

GERGIS: At a year and a half, she has moderate/severe chronic GVHD. Initially she responded to steroids, but the case does not say whether she’s still on steroids….Let’s assume that she’s not on steroids. What steroid dose is optimal, if that’s what you would do, and does a more aggressive starting dose improve outcomes? I think if we have to choose between 3 steroid doses—let’s assume she’s a year and a half after transplant, moderate to severe chronic GVHD, and she is not on immune suppression. Would you start her on a 0.5 mg/kg, 1 mg/kg, or 2 mg/kg or would you do something else?

ROWLEY: She’s only 35 years of age and you’re possibly dealing with chronic and permanently dry eyes, which have a great impact on the quality of her life, and now with the evidence of developing lung GVHD, which doesn’t repair, I think that could be a dramatic change [in] the quality of her life. We’re changing her from AML to chronic GVHD and all the consequences of that. I would start 1 mg/kg but be looking carefully at the response to this, particularly in terms of the lung GVHD.

GERGIS: Would you start back calcineurin inhibitors at this time?

ROWLEY: Generally, I do not add a calcineurin inhibitor. Because we have access to photopheresis for lung GVHD, I would want to start the photopheresis at the same time.

GERGIS: How about her skin? Did that impress you and push you to do photopheresis?

ROWLEY: The skin can reverse in response to the therapies that you initiate; whereas, the lung GVHD, once you impair the lungs, especially if it progresses, you’re talking about lung transplants. This could potentially be a disaster if you don’t get this woman’s disease under control fairly quickly.

GERGIS: I think the consensus is to start steroids at 1 mg/kg, keep an eye on her lungs, and have a low threshold to move on into second line if she progresses or does not respond.

The responses in acute GVHD are rather dramatic and quick, and chronic GVHD takes more time and needs more experience, in my opinion. If a transplant center is [seeing] a high volume of these patients, even the transplant center may not have the resources or the expertise to follow these patients. They are more involved. In the acute GVHD setting, oftentimes they are hospitalized, and the nutritionist is on the floor, the rehabilitation people are involved. For chronic GVHD, patients are usually back home, and they come to see us every month, and if I’m in a conference and covered by [another physician], they may not notice the subtle changes in the range of motion and other things [in the patient]. Personally, I find looking after patients with chronic GVHD is more involved than [treating those] earlier on in the transplant course.

How do you feel about peripheral mobilized stem cells versus bone marrow biopsies for these patients?

GERGIS: When I was at [Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida], we were part of this trial comparing peripheral mobilized stem cells versus bone marrow, and then a plenary session [presented] there showed less chronic GVHD in the marrow.1 At the time, I was doing a harvest about once a week, and when the trial came positive, I thought I’d probably be doing much more. I hated doing harvests [because] I don’t think it changed any practice and I was wondering why.

In my opinion, [transplants] became more popular around this time and it increased the incidence of acute GVHD significantly.

ROWLEY: It really is doctor specific. We have a doctor up there who does not want to use peripheral blood for the haploidenticals, so [they] will insist upon bone marrow biopsy for that. I’m much more flexible in terms of my graft choices. I choose the graft [based on] the patient’s needs. If I have a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome or prolonged cytopenias, I want peripheral blood to give me the quick in-graft but I’ll [take longer] with the chronic GVHD.

There’s also the consideration that harvest teams are becoming less and less experienced with the graft that you get, especially when you go outside your center to an unrelated donor center; [they] may not have the same quality of what it would have been 10 years ago.

What does GVHD affect most in patients?

GERGIS: Chronic GVHD affects all organs, the most common skin, then buccal mucosa in the mouth, eyes, and other organs. The lungs are the most devastated. I had to refer a few of my patients to lung transplant.

The [National Institutes of Health] scoring system looks at the organ that is affected; you give it a score, and you go organ by organ—mouth, eyes, skin, esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, liver.2 From all these scores, you make up 1 of 3 categories: mild, moderate, or severe. Chronic GVHD requires a lot of expertise and a very involved multidisciplinary approach. Most centers have some sort of a survivorship or chronic GVHD clinic dedicated for this group.

Which treatments are used in second line for chronic GVHD?

GERGIS: Ruxolitinib [Jakafi] is being studied in a good phase 3 trial. I think it’s completed accrual, and we’re waiting for analysis.3 We [conducted] a trial comparing rituximab [Rituxan] versus ibrutinib [Imbruvica]. Imatinib [Gleevec] was approved based on a small trial. I know at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute they use a lot of interleukin-2. It’s a muddy and center-specific treatment when it comes to second and third lines.

Ibrutinib was approved based on a small trial with efficacy of 69%; it was fairly safe, and I think most oncologists feel comfortable giving these oral drugs, but it’s not that great.

ROWLEY: The phase 3 [trial] looking at ibrutinib plus corticosteroids versus corticosteroids has completed its accrual and the data are being analyzed. I expect to see results to be coming out in the near future. It’s [been] approved [based] on a phase 1b/2 study.4

What do you think of the answers from this poll? What would you choose?

GERGIS: Most have chosen ibrutinib. A couple of us like ruxolitinib. Oftentimes you choose one and you move onto the other [because of] adverse effects and other issues.

Whether it’s ibrutinib or ruxolitinib, they come with their own adverse effects: fatigue and muscle pain; ruxolitinib has cytopenia and especially thrombocytopenia; ibrutinib has diarrhea, bruising, and atrial fibrillation. The treatment for chronic GVHD is long, and most people will have other problems; dyslipidemia, steroid myopathy, osteoporosis, so again, they need multidisciplinary approach and an involved and experienced center.

ROWLEY: What I generally will do with a patient, if I’m starting them on steroids for chronic GVHD, is I will also start them on ruxolitinib at the same time, because I’m going to want to get them off the steroids before I end up with a lot of the adverse effects, and ruxolitinib has been a well-tolerated medication.

Sometimes I have to cut back the dose a bit for a short period of time because of anemia. I haven’t seen so much thrombocytopenia, but I have seen anemia where I’ve had to go from 20 mg a day to 10 mg a day before I can build it back up, but it’s been a well-tolerated drug. You asked me if I would treat with a calcineurin inhibitor. It is typically steroids plus ruxolitinib.

References

- Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1487-1496. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1203517

- Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(12):945-956. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004

- NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT): pre-transplant recipient evaluation and management of graft-versus-host disease; version 2.2020. March 23, 2020. Accessed September 1, 2020. http://bit.ly/2QGtt2M

- Waller EK, Miklos D, Cutler C, et al. Ibrutinib for chronic graft-versus-host disease after failure of prior therapy: 1-year update of a phase 1b/2 study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(10):2002-2007. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.06.023