ACCC Creates Resources for Multidisciplinary Practices to Prepare for Growing Geriatric Cancer Population

To help clinicians cope with an increasing number of geriatric patients with cancer, the Association of Community Cancer Centers is addressing this problem with a 2-pronged approach that focuses on the delivery of care and diagnostic assessment.

Facing a tsunami of aging baby boomers, with some estimates suggesting 10,000 people turning 65 years of age each day, oncologists and hematologists brace for a crisis in cancer care; these effects will only increase as more diagnoses, treatments, and financial stressors accompany the disease.1To help clinicians cope, the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) is address­ing this problem with a 2-pronged approach that focuses on the delivery of care and diagnostic assessment.

TheMultidisciplinary Approaches to Caring for Older Adults with Cancerprovides a how-to guide to improve the quality of care for geriatric patients that dicusses the current standards and explores potential improvements.2

“Any member of the cancer team can take this training, then take it back to their team and figure out the workflow that is appropriate for their own program or institution, and we’re hop­ing that it will lead to [change], even if a cancer program is doing some of the formal strategies in each of the domains of geriatric assessment,” Elana Plotkin, senior program manager of pro­vider education for ACCC, said in an interview withTargeted Therapies in Oncology.

To make sure oncology practices and pro­viders are ready to handle the quickly rising number of patients who will be diagnosed with cancer, which will be 70% of the projected 2.3 million cancer diagnoses by 2030, ACCC used a landscape analysis, focus groups, and interviews with stakeholders across the coun­try to gather the dataand subsequently, the materials—multidisciplinary teams will need to be prepared.

Three cancer centers that worked with ACCC to demonstrate the different approaches for handling the personalized care of older patients and their needs were highlighted in the guide.

The Ted & Margaret Jorgensen Cancer Cen­ter at Presbyterian Rust Medical Center of Presbyterian Health System in Rio Rancho, New Mexico, reassessed their delivery of geriatric care after 2 employees received training on geriatric assessment tools and how to imple­ment them for patient care.

A Senior Adult Oncology Center has been running at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson Health, Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, since 2010, where all of the members of the multi­disciplinary team see a patient during a single visit and have a full consultative report within 48 hours.

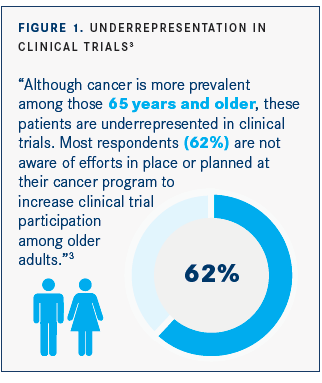

Lastly, the City of Hope Comprehensive Can­cer Center, in Duarte, California, has the Center for Cancer and Aging and Cancer and Aging Research Group that “connects geriatric oncol­ogy researchers in a collaborative to design and implement clinical trials to improve the care of older adults with cancer,” according to the publication(FIGURE 1).3

In Plotkin’s opinion, from working with these different groups, the practices that are providing the best geriatric care are putting the whole patient first by looking at all the dif­ferent domains of geriatric assessment such as cognition, functional status, nutrition, psycho­logical health, comorbidity, social support, and medications. This step ensures there is com­munication across teams, the older patients are being treated according to their current phys­ical status and their ability to handle different treatment regimens based on the assessment, and their goals of care and quality of life are being prioritized by the oncology team.

“The majority of cancer cases are diagnosed in older adults. To care for this population, it is important for health care professionals to be aware of the common age-related vulnerabilities and how they [affect the patient with] cancer and cancer treatments,” advisory committee member Melissa Kah Poh Loh, MD, MSc, with Combined Geriatrics and Hematology/Oncology at the Uni­versity of Rochester, said in a statement.4

ACCC used the landscape analysis to shape their recommendations, in addition to inter­views and focus groups. They began the task of putting it together in 2018 when individual members of ACCC, who were a part of multidis­ciplinary cancer teams throughout the United States, started reaching out with concerns about their older patients.

“They realize that there may be opportunities for improvement in terms of different screening protocols, identifying patients for appropriate care, and care coordination amongst their teams to reflect a patient’s journey,” Plotkin said.

After receiving funding from Pfizer Oncology to develop a program studying geriatric care throughout the country, ACCC assembled the landscape analysis with their expert advisory committee. The committee is a multidisci­plinary group representing diverse oncology providers with programs varying in size and shape, according to Plotkin. Experts from the Gerontological Society of America (GSA) and the International Society of Geriatric Oncol­ogy (SIOG), partners of ACCC, are also on the committee.

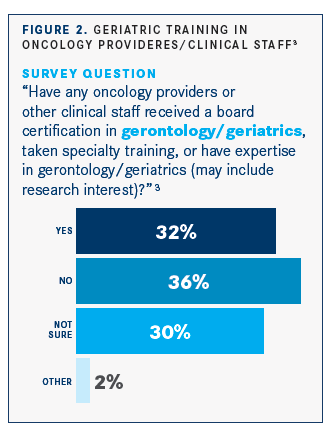

The survey was filled out and returned by 332 multidisciplinary cancer program team members throughout the country. The respon­dents were comprised of many professions in the oncology field, such as pharmacists, admin­istrators, physicians, psychologists, investiga­tors, advanced practice providers, nurses and nurse navigators, and social workers. They were asked about each area of comprehensive geriatric assessment that is found within the guide. Through the analysis, Plotkin said they discovered these practices were not formalized or standardized across the board; one of the reasons for this was the lack of training in the geriatrics setting (FIGURE 2).3

“We were surprised at the level of informality that was [present when] each program self-as­sessed for these areas,” Plotkin explained. “For example, when looking at psychosocial con­cerns and depression, [one of] the top answers from our survey was that cancer programs informally ask the patient during a conversa­tion if they are depressed [34%]. We’re trying to encourage, in all the domains of geriatric assessment, that they use a more formal-struc­tured approach [such as the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment]. It’s information that can be put in the patients’ electronic health record and tracked over time.”

Adding structure to the way oncology providers treat older patients will help give them a better understanding of the patient as a whole and their individual needs. InMultidisciplinary Approach­es to Caring for Older Adults with Cancer, it’s clear that providing care to geriatric patients reflecting every part of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in the guide can be chal­lenging, and there are reasons that not all cancer teams use a more in-depth assessment for their older patients.

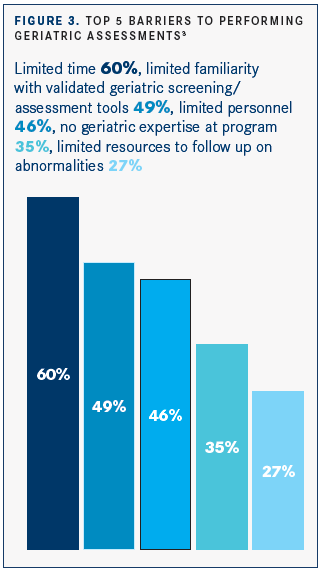

“In our survey, the top concerns for teams not doing a comprehensive geriatric assess­ment were time and resources. We realized that physicians only have a certain amount of time with each patient, so we’re advocat­ing for the entire multidisciplinary team to be empowered to complete different areas of the geriatric assessment pertinent to their specialty and to be involved in the care. Some screening tools can be done in advance, so it doesn’t burden staff when a patient arrives,” Plotkin suggested. “We think [this] can all be done within the current time constraints and without adding too much burden, but the whole team needs to be on the same page and be involved” (FIGURE 3).3

Another concern is, with the growing num­ber of older patients, community oncology providers will be affected even more than other groups because it’s ideal for these patients to be treated near their home, according to Plot­kin. “It’s important that [patients] are able to access appropriate care in a location that’s close to them and their caregiver, especially as mobility issues and things like that dispro­portionately affect older adults; being able to access that close-to-home care is critical.”

Plotkin said they are working on a how-to guide for oncology programs to make sure the different tools and assessments are incorporated into the Comprehensive Geriatric Assess­ment part of their practice even if they don’t have many resources to put toward it, like some smaller community practices.

As a result, ACCC has developed a webinar series presented by leaders in the field and focused on the data their geriatric program has accrued. The overarching point of the series was to express that the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment is necessary for geriatric patients, which data has confirmed, and encourages cancer programs to start with attainable goals that work for their setting.

“We’re hoping that as teams learn the impor­tance of why this needs to be implemented and practiced, that they’re able to take our education and then make changes within their cancer pro­gram,” Plotkin said.

The series, along with an abundance of other resources such as theMultidisciplinary Approaches to Caring for Older Adults with Cancer,Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, screen­ing tools, and specific status assessments, can be accessed for free on the ACCC website at accc-cancer.org/geriatric.

Going forward, the next task on ACCC’s list is creating a gap assessment tool, which can be taken by anyone in the oncology field. It will measure the domains of geriatric assessment, specifically what each participating organization is currently doing to meet the requirement, then give a score based on the answers about their practice and provide recommendations on how to improve different aspects by connecting them to resources available in each domain.

“I am fortunate to have worked with the ACCC leadership and other experts in geriatric oncolo­gy to develop education materials that are prac­tical and easily translatable into clinical practice for health care professionals. I strongly believe that this project will serve as a model for other organizations whose goals are to improve care in the geriatric oncology population,” said Loh.

In conclusion, the quality and understanding of geriatric cancer care can be improved throughout all cancer programs with the resources provided by ACCC and its collaborators. The materials it is offering can be implemented by any professional in the oncology field to enhance the care they deliver and meet the challenge of the wave of older adults who will be diagnosed with cancer.

References

- Cohn D, Taylor P. Baby boomers approach 65-glumly. Pew Research Cen­ter Social & Demographic Trends website. pewrsr.ch/2RO0QAP. Published December 20, 2010. Accessed January 24, 2020.

- Multidisciplinary approaches to caring for older adults with cancer [news release]. Rockville, MD: Association of Community Cancer Centers; December 19, 2019. bit.ly/2SkmMDT. Accessed January 24, 2020.

- Plotkin E, Dotan E, Nightingale G, et al. Growing need demands new approaches to caring for older adults with cancer. bit.ly/2TOQZgS. Published July 11, 2019. Accessed January 24, 2020.

- ssociation of community cancer centers calls attention to impor­tance of geriatric assessment in caring for older adults with cancer. ACCC website. bit.ly/36ZfVoU. Published December 16, 2019. Accessed January 24, 2020.

Therapy Type and Site of Metastases Factor into HR+, HER2+ mBC Treatment

December 20th 2024During a Case-Based Roundtable® event, Ian Krop, MD, and participants discussed considerations affecting first- and second-line treatment of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer in the first article of a 2-part series.

Read More

Participants Discuss Frontline Immunotherapy Followed by ADC for Metastatic Cervical Cancer

December 19th 2024During a Case-Based Roundtable® event, Ramez N. Eskander, MD, and participants discussed first and second-line therapy decisions for a patient with PD-L1–positive cervical cancer in the frontline metastatic setting.

Read More