Tweet Chat Recap: Using Immunotherapy and Targeted Therapy for BRAF-Mutant Metastatic Melanoma

In an interview with Targeted Oncology, following the tweet chat, Shoushtari highlighted the key takeaways from the tweet chat discussion and spoke to how he would make his own treatment decisions for this patient scenario.

Alexander N. Shoushtari, MD

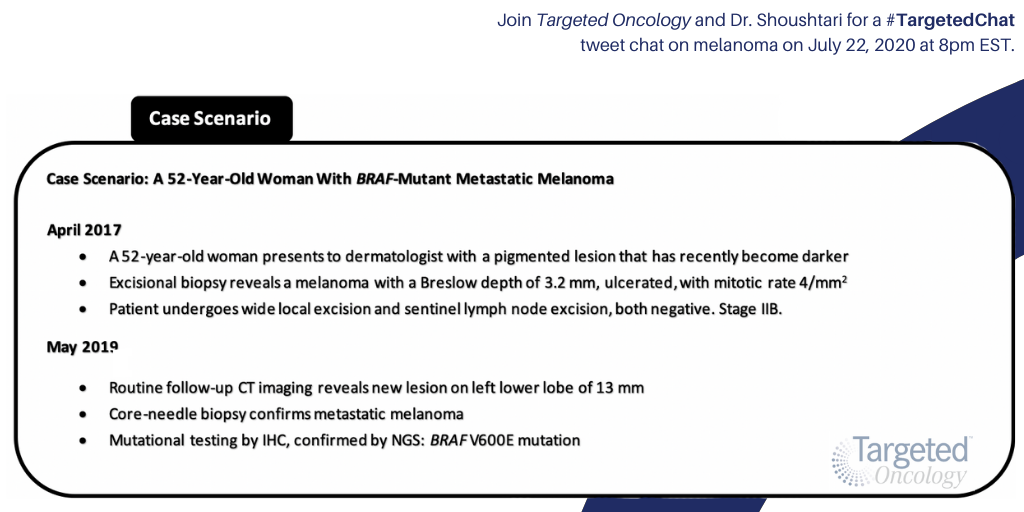

Targeted Oncology was joined by Alexander N. Shoushtari, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, for the discussion of a 52-year-old woman with BRAF-mutant metastatic melanoma in a recent tweet chat. In this case scenario, the patient presented in 2017 with stage IIB melanoma and underwent wide local excision and sentinel lymph node excision. She returned in 2019 with BRAF-mutant metastatic disease.

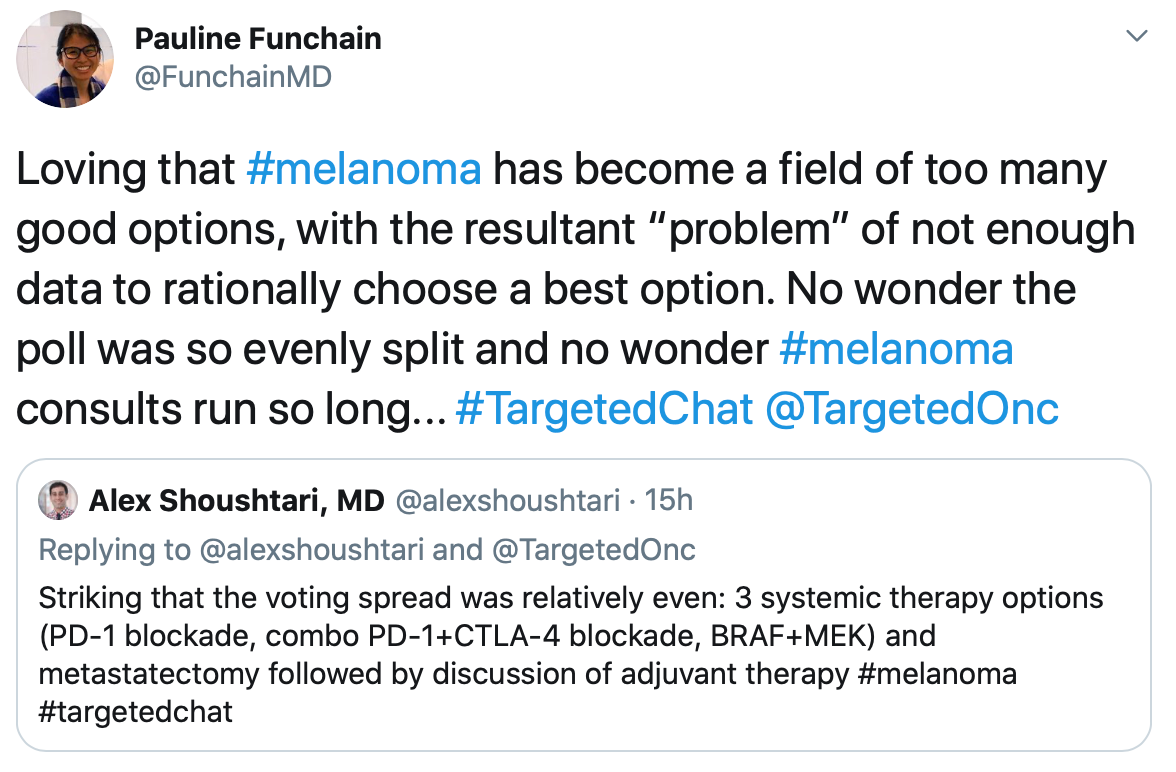

In a Twitter poll ahead of the discussion, Targeted Oncology followers shared their thoughts on what might be the next best line of therapy for this patient. Overall, the majority in the poll (30.2%) selected the combination of nivolumab (Opdivo) plus ipilimumab (Yervoy) as the next best line of therapy, while checkpoint inhibitors still appeared favorable with 27.9% voting for either pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or nivolumab monotherapy. Additionally, 25.6% opted for surgery followed by an adjuvant taxane. The combination of a BRAF inhibitor and MEK inhibitor drew the least amount of attention of the 4 choices (16.3%).

Surprisingly, the poll appeared to be divided between the 4 different treatment options, but Shoushtari was surprised to see fewer votes for the upfront metastasectomy for the case of low-burden, untreated disease. Overall, in this day in age, there are many good options available for patients with melanoma, which appeared to be the general consensus on this chat.

Shoushtari said he would personally choose immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy for this patient case, particularly because of the toxicities associated with immunotherapy. Despite the research showing that addition of another immunotherapy can improve progression-free survival benefit, Shoushtari would prefer not to add extra toxicities with a second agent. In terms of selecting either nivolumab or pembrolizumab, he tweeted, “The major difference, since they have never been compared head to head, is the dosing schedule. Nivolumab [is] available as every 2- or 4-week dosing; pembrolizumab [is] available as either 3- or 6-week. Most, otherwise, would consider them equivalent.”

Although he would choose checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy, all 4 options can be useful for this patient. He tweeted that there are, “no clear answers about which option has the best “cure” rate, so would tailor [recommendations] to personal preferences.”

In an interview with Targeted Oncology, following the tweet chat, Shoushtari highlighted the key takeaways from the tweet chat discussion and spoke to how he would make his own treatment decisions for this patient scenario.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: Before we get into the discussion from our poll, can you review how immunotherapy and targeted therapy have evolved in this space?

Shoushtari: For those of us who treat patients with melanoma, we're always excited and hungry for more advances. The PD-1-based therapies have changed a lot about how stage IV melanoma is treated, and increasingly it's permeated into the patient level experience. Patients are no longer as terrified as they were 5 to 6 years ago when this was just starting out. Targeted BRAF inhibition with MEK inhibition, in particular, just adds another tool to the arsenal for the roughly 40% of patients to 50% with skin melanoma in western populations. It's not an option for everyone, unfortunately, and particularly in other countries and ethnicities, but there are other melanoma subtypes that lack that target therapy option. However, the checkpoint inhibitors, the so-called immunotherapies, are used for almost all cases with some excellent results.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: What were your initial thoughts when you looked at this patient case?

Shoushtari: I think it's a purposely constructed case where there's a few ways you can go. To me, it was relatively common scenario where somebody has an early or intermediate stage melanoma and is not a candidate for preventative or adjunctive therapy. Then on surveillance, you end up finding a stage IV recurrence, and you have to run the gamut of those 3 major options for systemic therapy. One option is doing surgery first and then considering preventative therapies. This is a choice we have to make all the time in the clinic. I think the choice for immunotherapy, so 1-drug with nivolumab or pembrolizumab or combined PD-1 and CTLA4 blockade with nivolumab and ipilimumab, that's a bread and butter choice. That's something that we always wrestle with, and there's really no convincing statistically significant data that using both drugs are necessary for everybody.

There are some people who would disagree with the way I interpret those data and might say, “well 2 drugs do lean a little bit closer towards the survival benefit”. It does have more toxicity, so that's always a patient-level decision that you have to have with the person in front of you. In this case, we are not dealing with a very complicated backstory of an immune condition like an inflammatory bowel disease or something that would influence us, so it becomes a personal choice.

The targeted therapy is interesting. I think, again, for a lot of people, once you start the pills, you're stuck on them, and some of these patients hate that idea. Some doctors hate that idea, too. I think if you have a lot of disease and you need fast shrinkage, the data would guide you towards probably starting with the targeted therapy.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: Can you talk more about the toxicities that we see with immunotherapy and what's important to consider when using these therapies?

Shoushtari: Maybe it's because it's the vast majority of what I do, but my toxicity talk with my patients is usually a pretty long one because I talk about kind of 4 distinct groups of side effects. One is the majority of people get mild stuff, and that's not so bad. When most people will talk about immunotherapy being, “easier than chemotherapy” or something like that, they're thinking about those mild side effects like itching, rash, or mild fatigue. For most people, the good news is that's usually as bad as it gets.

I think of the second group of side effects as being, to the oncologist, not a huge deal, but they are sort of permanent, and those are like the thyroid effects or other endocrine or hormone gland dysfunction effects, which can be permanent. For some older people, they take 6 pills already for various ailments or they may even be on a thyroid medicine to start, so it's not as big a deal as to a young person, who may not know how thyroid changes affects, for example, the menstrual cycle, their long-term fertility, or their bone health. That may be a bigger consideration.

Then there's a couple of other groups that I always try to mention. That would be the group of reversible side effects, which [require] steroids. Depending on the person, being on steroids for a few weeks is no big deal or it can be a really significant comorbid condition where their blood pressure goes up, their blood sugar goes up, it's annoying, they can't sleep at night, or something like that. It’s a significant minority of patients with 1 drug, and that's at least half of patients. When we use both drugs, they have to be on steroids at some point. Some of the earlier data said maybe up to up to three-quarters needed steroids, but the fourth group, and the thankfully rarest, is the scariest stuff, the ones we've linked to in the chat from Jama Oncology. The most common 1 that haunts us is called myocarditis. The heart inflammation happens about in 1 in 100 people and in that publication, about one-third of people with that died of that, so it's not insignificant.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: The targeted therapy combination of the BRAF and MEK inhibitors received the least attention of the four options in our Twitter poll. Why do you think that is?

Shoushtari: It's interesting. There's a large group of patients with BRAF V600-mutant melanoma that do get BRAF and MEK inhibitors as their initial treatment. For most people in the academic space and maybe in the Twitter-oriented space, medical oncologists are a little bit more skewed towards immune-based therapy because of that flexibility with the duration of treatment and the flexibility with dosing. Sometimes you can delay a week or 2, and it's no big deal for most patients. I think that's really attractive if you get a response that you think that you can stop at some point. With targeted therapy, it is clear that people can stay in response for years on end, and we didn't know that initially. We thought it was only with immunotherapy that you would get a so-called plateau in the curve of progression. That's not true. You can get 3 to 5 years out and still be on the pill successfully, but you have to take [an upwards of] 11 or 12 pills a day to do so, and I think that is a potential downside.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: Why our BRAF inhibitors not considered for use as monotherapy?

Shoushtari: That’s 1 of the few things that I can definitively say has a clear answer. There's been a series of studies now that all compared BRAF with a MEK inhibitor against a BRAF inhibitor, and they all showed that adding a MEK inhibitor not only improves progression-free survival or the duration of disease control but actually overall survival as well. All of these were generally done in the era without a lot of prior PD-1 inhibition. All of these were largely done in either ipilimumab-treated or untreated populations, but I don't think anybody expects that to be a difference in this current era. Using them together is a definitive standard of care.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: Are there other factors that would lead you to consider surgery followed by adjuvant therapy in this particular patient case?

Shoushtari: The surgical option was probably the easiest to dismiss for me. I prefer to leave the tumor in place for 2 reasons. One is the treatments can be just as successful, and we know from the large trials in stage IV disease that you can get complete responses or partial responses that last for years and years. I think the second reason is that sometimes you want to know if that treatment is going to work if you're going to pursue a preventative treatment after surgery anyway. In that case, let's say I put you through an extra surgery, and then I don't know if the treatment I'm using is working. That's the reason that I reserve the use of surgery for the carefully selected patient where I'm not sure I’m going to do any treatment at all, so we just want to buy them a couple of years of, hopefully, disease-free time without any treatment.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: Looking at this patient case, how would the development of brain metastases potentially impact your treatment decisions here?

Shoushtari: Brain metastases, statistically, is a worse scenario. It's an area that is very sensitive to slight increases in tumor volume and where salvage treatments are often more complicated to administer. Clinical trials are harder to get into once you have them, so for all those reasons, we tend to be more willing to take immune side effect risks, for example, ipilimumab 3 mg/kg plus nivolumab 1 mg/kg is often the go-to upfront on the basis of the CheckMate 204 trial that showed some nice disease control in asymptomatic cases.

If people are experiencing symptoms that require steroids or larger tumors, you're going to have your neurosurgeon and your radiation oncologist that you're consulting with. It’s true multidisciplinary care, and the presence of steroids, if there's a BRAF V600 mutation, being on steroids would help lean you toward using maybe the target targeted therapy upfront. The targeted therapies, we know from the trial data, don't control the disease quite as long in the brain as they seem to do in the rest of the body, whereas the checkpoint inhibitors seem to work just as long in the brain as the outside the body. They don't work quite as often, but not much less often, so for that reason, the presence of symptoms, how big it is, and whether they're on steroids tilts you towards either combination immunotherapy or monotherapy.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: What are your key takeaways from this case and the overall tweet chat discussion?

Shoushtari: I would want to get across in every patient encounter or if I'm discussing the case with other medical oncologists, it is not whether they could do well, it's about how we are going to get there. Not everybody is lucky enough to get disease control, but you have at least 3 good options to get there and potentially a fourth. I think getting that across in the patient encounter is very important. I think knowing the side effects and knowing your own comfort level will help guide you and your discussion with the patient to say, should we start with 1 drug or 2 if we're doing immunotherapy?

If we're doing targeted therapy, this is going to be in probably for the long haul. The side effects are more front-loaded, usually by the time you get past the first few months. That’s a little bit different than immunotherapy where you can get surprises, so to me, it's very much a sort of side effect-driven discussion. That's individualized. We don't have landmark trials, like in mine breast cancer where they've been individually laid out, in terms of which medical treatments are better used in which order, we have not yet been able to do that.

TARGETED ONCOLOGY: What advice would you like to share with a community oncologist treating patients with melanoma?

Shoushtari: For the majority of community oncologists, they're increasingly pretty well equipped to handle folks that have no existing immune conditions and are untreated. I know because I'm seeing fewer of them in my clinic, for better or worse. I would say, you should know your referral base for your other medical subspecialties things like who's going to be your gastroenterologist hepatologist, endocrine specialist, rheumatologist, cardiologist, etc. If you have your good network of standby folks for immunotherapy, I think that is key, especially if you're going to use 2 immunotherapy drugs at the same time. Otherwise, I would, I would let them know that there still is a lot of research going on in, and if that initial therapy doesn't work, so if BRAF and MEK inhibitors don't work, we've got a lot to offer, and increasingly, clinical trials are coming into the community, which is great.