Integrating New Therapies With Autologous Stem Cell Transplant in Myeloma

Saad Z. Usmani, MD, MBA, FACP, FASCO, discussed how the role of autologous stem cell transplant is evolving in the myeloma treatment landscape with the emergence of CAR T-cell therapies and bispecifics.

Saad Z. Usmani, MD, MBA, FACP, FASCO

The role of autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) in multiple myeloma treatment is evolving. While newer therapies like chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies show promise, ASCT still sets a high bar in terms of patient outcomes.

For patients who are deemed high-risk, particularly those at risk of early relapse, ASCT remains the most beneficial option, according to Saad Z. Usmani, MD, MBA, FACP, FASCO. Still, Usmani anticipates a diminishing role for ASCT in the future, as novel immune therapies gain traction, but emphasizes the need for data to support this shift.

“Despite the fact that we have tried to displace [autologous stem cell transplant] from the frontline setting, we have not been successful because [autologous stem cell transplant] sets a high bar, in terms of outcomes for patients. But the newer therapies may be able to replace autos, and that is where we are heading,” explained Usmani, chief of the myeloma service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, in an interview with Targeted OncologyTM.

Ongoing clinical trials are currently exploring novel CAR T-cell therapies and bispecifics, as well as integrating ASCT with such therapies to tailor treatment for different patient subsets. Usmani further discussed this topic during the Fifth Annual Miami Cancer Institute Global Summit on Immunotherapies for Hematologic Malignancies, hosted by Guenther Koehne, MD, and Miami Cancer Institute.

In the interview, Usmani discussed the evolving role of ASCTs in the multiple myeloma treatment landscape, including their best practices, ongoing clinical trials, managing toxicities, and more.

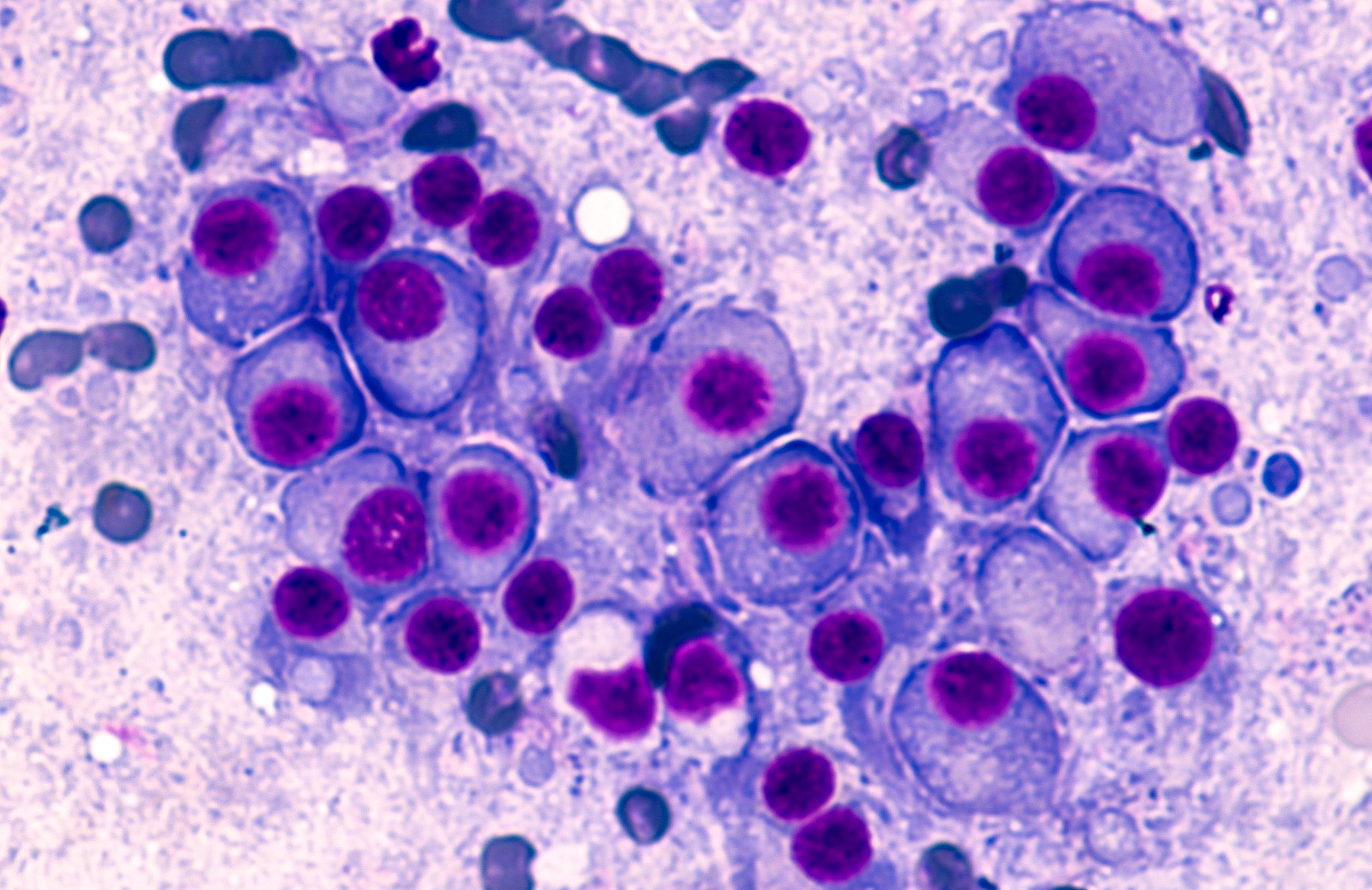

Multiple Myeloma: © David A Litman - stock.adobe.com

Targeted Oncology: With the continuous development of novel therapies for multiple myeloma, how has the role of autologous stem cell transplant changed the treatment landscape?

Usmani: I have been answering this question now for 15-plus years, and many people were doing this even before I got into the field. There is some historic context to that. Novel therapies started to make their way into myeloma back in the late 90s, early 2000s. The real question was, can you give the same depth of response to patients so that they do not have to go through high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell rescue, because their [adverse] effects and recovery time period after that is an involved process. Now, we have effective single-agent activity with bispecifics and CAR T-cell therapies. Despite the fact that we have tried to displace [autologous stem cell transplant] from the frontline setting, we have not been successful because [autologous stem cell transplant] sets a high bar, in terms of outcomes for patients. But the newer therapies may be able to replace autos, and that is where we are heading.

Are there any specific patient subgroups for whom autologous transplant remains the best course of action for?

For high-risk patients specifically, I think incorporating autologous stem cell transplants is very important. The way that we define high-risk is any active patient [with myeloma] who is at the risk of relapsing early and dying from disease within the first 3 to 5 years of diagnosis. For those patients, we do not get many opportunities to control the disease, so this is where I think autologous [stem cell transplants] become important. For some of the standard-risk patients who have low disease burden, sometimes it becomes a discussion around quality of life and whether they want to prioritize their lifestyle right now compared with getting into an autologous stem cell transplant. For high-risk patients, it is clear from the available data that it needs to be part of the treatment schema.

Can you elaborate on the current best practices for determining the optimal time for transplant in these patients?

I think the overarching theme for us is we want to get patients into very deep responses during the first year of diagnosis and try to maintain patients in that deep response. This is where I think the role of autologous stem cell transplants comes into play. We do not have any clinical trials right now that have shown us that if we get to, say [minimal residual disease]-negative status, that we can hold everything. We just don't have that randomized data yet, but I think that kind of data is being generated and that will help inform us. The overarching theme is to get patients the best depth of response during that first year of diagnosis, and [autologous transplants] help both standard-risk and high-risk patients in that regard.

How does one minimize treatment-related adverse effects associated with these transplants?

The supportive care measures around autologous stem cell transplants have improved quite a lot in the last 15 years. I think identifying the right patients and providing them adequate support [will] help minimize the [adverse] effects. Autologous [transplants] have become an outpatient procedure at many centers, so providing patients logistic support to be outside the hospital and be in a more comfortable environment also helps with the mental health aspect of it.

How do you see the role of autologous stem cell transplant evolving in the treatment of multiple myeloma?

If the emerging CAR T-cell therapies and bispecific antibodies continue to show good safety profiles in randomized clinical trials [and if they] can show comparable outcomes but better tolerability of therapy, then I think autologous stem cell transplants may take a backseat. But I do not think we will get to that point in the next 5 or 6 years. I am talking about a 10-year horizon, because these clinical trials will need to be conducted and read out to make that point. In the immediate future, I think autologous transplants will play a role in the newly diagnosed setting, but we will continue to have a diminishing role in the future based on data. I do not want to say anything without having data to back that up, but novel immune therapies are the future. That is an aspirational goal for us. We all want to minimize [adverse] effects for our patients. If we are able to accomplish and prove that point, then yes, autologous stem cell transplants will be displaced from frontline treatment.

Are there any ongoing clinical trials investigating the integration of autologous stem cell transplant with other promising therapies?

Yes. There are some randomized phase 3 studies that are running in the United States as well as European countries and some global studies where we are comparing autologous stem cell transplant to CAR T-cell therapy in the frontline setting, or CAR T even in transplant-ineligible or transplant-deferred patients, giving CAR T vs maintenance treatments. Some of those clinical trials will be read out. There are other clinical trials that are trying to combine a sequence of autologous transplants followed by CAR T high-risk patients. Instead of the tandem autologous approach, can you control the high-risk disease preventing its relapse by giving CAR T-cell therapy after an autologous transplant? There are other ideas trying to incorporate bispecifics into consolidation and maintenance strategies to accomplish the same. Many different ideas are being tried and we are trying to come up with the right recipe for the different subsets of patients [with myeloma].

What would you want your colleagues to take away from this talk?

The key message is that we have come a long way in myeloma therapeutics. When I was in my early training years, the approach to treating myeloma used to be that you did not have many options. We would treat myeloma when patients are symptomatic for a little period of time. Any response is better than no response. Then [we would] just hold tight if some symptoms happen or relapse happens, [we] treat, and most patients would not get more than 2, maybe 3 lines of treatment. Now, myeloma is a chronically managed condition, and things have come a long way. Our best shot with myeloma is at the time of initial diagnosis, so picking the right strategies for patients to get them into deep responses in that first year of diagnosis is important. That is what translates into a better survival outcome.