Chipping Away at the Surface of Melanoma Treatment: Narrowing Down Therapies

A guideline from the American Society of Clinical Oncology addresses 4 clinical questions regarding approaches to systemic treatment for different types and stages of melanoma, in addition to summarizing the trials on which the recommendations were based.

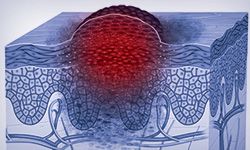

With many systemic therapy options available for the treatment of patients with melanoma, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) gathered together an expert panel to create guideline recommendations for choosing the optimal agent at multiple stages of the disease (FIGURE).1 They covered 1 systematic review, 1 meta-analysis, and 34 randomized trials to compile the new set of recommendations for treating patients with various stages of melanoma.1

When asked how treatment options have changed in the last 5 years, Rahul Seth, DO, lead author of the guideline, said, “Melanoma is a field that has undergone a revolution in terms of treatment options and treatment outcomes.” With so many therapies available and new ones being tested every day, deciding on a treatment regimen can be difficult.

Targeted Therapies in Oncology asked Seth, an assistant professor of medicine at State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, if there were any therapy regimens not listed in the expert recommendations that he felt had merit. “The short answer is no, the ASCO guideline [was] pretty exhaustive in all aspects,” he said.

The guideline addresses 4 clinical questions regarding approaches to systemic treatment for different types and stages of melanoma, in addition to summarizing the trials on which the recommendations were based.

Unresectable Melanoma

The evidence supporting the panel’s advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with melanoma who are ineligible for surgical resection was primarily based on a 2018 Cochrane Review, which included data from 122 randomized clinical trials through October 2017.1,2

The guideline indicates that patients with BRAF wild-type unresectable/metastatic cutaneous melanoma should be offered, in no significant order, combination ipilimumab plus nivolumab followed by nivolumab, single-agent nivolumab, or single-agent pembrolizumab.

Historically, patients in this population received chemotherapy with or without interferon and/or interleukin-2 (IL-2), but therapy success was limited and toxicity incidence was high. When introduced, the CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab induced better progression-free survival (PFS) but also greater toxicity. Phase 3 results from trials comparing experimental regimens of ipilimumab (Yervoy) versus nivolumab (Opdivo; CheckMate 067, NCT01844505) or pembrolizumab (Keytruda; KEYNOTE-006, NCT01866319) showed significantly improved overall survival (OS) compared with the control arm of single-agent ipilimumab in both cases.

For patients with BRAF V600 unresectable/ metastatic cutaneous melanoma, the panel said the above regimens can be considered, in addition to BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations of dabrafenib (Tafinlar) plus trametinib (Mekinist), encorafenib (Braftovi) plus binimetinib (Mektovi), or vemurafenib (Zelboraf) plus cobimetinib (Cotellic).

“I do believe that gene mapping is necessary for patients, for there are possibilities to get targeted therapies which may benefit patients,” Seth said. “Efficacy can be increased, and we do recommend FoundationOne [CDx] testing if one has no options left.”

Each BRAF/MEK inhibitor combination may produce different toxicity profiles; therefore, switching between regimens may be beneficial for patients experiencing unmanageable toxicities. However, there are no data regarding the effects on efficacy of such a switch.

When compared with chemotherapy, single-agent BRAF and MEK inhibitors have produced superior OS and PFS in randomized clinical trials. But when both types of agent are combined, OS and PFS are superior to those with BRAF inhibitors alone. Phase 3 trials with results supporting these recommendations include the CoBRIM trial (NCT01689519) of vemurafenib and cobimetinib, the COM-BI-v trial (NCT01597908) of dabrafenib and trametinib, and the COLUMBUS trial (NCT01909453) of encorafenib and binime-tinib, all with a control arm of single-agent vemurafenib. At this time, no head-to-head data are available to inform clinicians as to the best combination therapy.

“Treating patients and handling their expectations and understanding of possible adverse effects is a huge part of practice,” Seth said. “I have found with more patient education [there are] better outcomes and a better quality of life.”

Recommendations for second-line treatment depend on the patient’s BRAF biomarker status and type of first-line agent. Patients with BRAF wild-type tumors who progressed on PD-1 inhibitors may receive ipilimumab or ipilimumab- based therapy; those with injectable lesions are eligible for talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) therapy. Evidence for second-line ipilimumab is based on a single previous trial that investigated this agent following IL-2 or chemotherapy. However, because that study’s first-line treatment was not a PD-1 inhibitor, the panel questioned its relevance and only weakly recommended this option.

Second-line recommendations for patients with BRAF V600 mutations include the BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations discussed above following frontline PD-1 inhibition; conversely, PD-1 inhibitors may be considered following frontline BRAF/MEK inhibition. For either group, ipilimumab or ipilimumab-containing regimens are a suggested alternative.

“Second-line therapies are chosen based on factors [related to] how the patient is doing with the current treatment,” Seth said. “There [are] no absolute criteria, but the clinicians decide based on the treatment options [that are out there].”

Patients who are ineligible or unwilling to receive systemic therapy or participate in clinical trials may be given T-VEC as an alternative primary therapy. Evidence from the phase 3 OPTiM trial (NCT00769704) demonstrated mixed results for T-VEC versus granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, with a significant improvement in median time to treatment failure (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.32-0.54) but not in OS (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.62-1.00). Additionally, grade 3/4 toxicity was somewhat increased in the T-VEC arm.

Adjuvant Therapy for Melanoma

The most recent FDA approval for a systemic melanoma treatment occurred in 2019, when the agency designated the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab as an acceptable adjuvant treatment for patients with melanoma with lymph node involvement following complete resection.3

The panel investigated different adjuvant systemic therapy options, alone or in combination, to determine the best options for use in adults with resected stage II to IV cutaneous melanoma.

Nineteen randomized trials were reviewed in this section of the guideline, most of which were found to have a low risk of bias. The panel primarily examined the recurrence-free survival (RFS) and OS rates. Recommendation 2.1 advises against adjuvant nivolumab, pembrolizumab, or combination therapy with dabrafenib and trametinib for patients with stage II disease due to the lack of positive trial data. The panel suggested that patients seek to enroll in a clinical trial instead.1

However, the panel determined that for patients with resected stage IIIA to IIID disease and BRAF wild-type tumors, a year of systemic therapy with a PD-1 inhibitor, either nivolumab or pembrolizumab should be offered. The recommendations advised against the routine use of interferon and ipilimumab in adjuvant therapy. Patients with BRAF V600E/K–mutant disease may consider the same therapies in addition to the targeted BRAF/MEK inhibitor combination of dabrafenib plus trametinib.1

It was determined that patients with resected stage III disease with minimal lymph node involvement have a lower risk of relapse, thereby making individualized therapy after shared decision-making talks with the patient preferred over a broad recommendation.1

The phase 3 CheckMate 238 trial (NCT02388906) in patients with stage IIIB/C or IV melanoma found nivolumab superior to ipilimumab in terms of RFS (HR, 0.65; 97.56% CI, 0.51-0.83; P <.001) and toxicity. A similar RFS advantage was seen with the use of pembrolizumab versus placebo in patients with high-risk stage III melanoma (HR, 0.57; 98.4% CI, 0.43-0.74; P <.001) in the phase 3 KEYNOTE-054 trial (NCT02362594).1

With no head-to-head studies available to compare nivolumab and pembrolizumab, the panel determined that either treatment plan would be an acceptable option for these patients.

Efficacy of the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib was explored in the phase 3 COMBI-AD trial (NCT01682083) in patients with high-risk BRAF V600E/K–positive melanoma following surgical resection. With a minimum follow-up of 3 years, the targeted therapy regimen had significant improvements in RFS (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.39-0.58; P <.001) and OS (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.42-0.79; P = .0006) versus placebo.

Randomized data testing the efficacy of interferon showed a significant benefit compared with observation. However, this was outweighed by the greater benefits demonstrated with more recently available agents coupled with the known toxicity of interferon, which led the expert panel to determine that interferon could not be recommended.

In the phase 3 ECOG-E1609 trial of ipilimumab at doses of 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg (NCT01274338), the CTLA-4 inhibitor had similar efficacy to interferon in terms of RFS and only showed improvement in OS at the lower dose (HR, 0.78; 95.6% CI, 0.61-1.00; P = .044). This result, coupled with data showing the superiority of nivolumab over ipilimumab, led the panel to determine that ipilimumab can no longer be recommended as a preferred agent.

For patients who have resected stage IV melanoma, the panel formed a consensus regarding single-agent nivolumab as the preferred agent based on evidence from CheckMate 238. The panel determined that pembrolizumab may be offered as an alternative to nivolumab, despite an absence of clinical data, based on similar efficacy of the 2 PD-1 inhibitors seen in key clinical trials. Dabrafenib plus trametinib may also be offered to patients with BRAF V600E/K mutations, particularly those who cannot receive or who cannot tolerate nivolumab.

Noncutaneous Melanoma

Because noncutaneous forms of melanoma— such as mucosal and uveal melanoma—are less common than cutaneous forms, trial-based evidence is difficult to obtain due to small sample sizes. However, the panel did address a few specific studies in making recommendations for treating these patients.

Several clinical trials included subgroups of patients with mucosal melanoma but had insuff icient numbers of patients for the panel to draw conclusions. One phase 2 trial of patients with mucosal melanoma found improved RFS and OS with temozolomide plus cisplatin chemotherapy versus interferon and observation, with similar grade 3/4 toxicities between the 2 nonobservation arms. However, the panel considered those results as artifactual given the small sample size; therefore, it recommended that patients with mucosal melanoma follow the guidance given for unresectable cutaneous melanoma.

In uveal melanoma, selumetinib (Koselugo) compared with either temozolomide or dacarbazine demonstrated an improvement in PFS that was statistically significant (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.30-0.71) but not clinically meaningful, and there was no difference in OS. The follow-up phase 3 SUMIT trial (NCT01974752) failed to produce improvement in either OS or PFS with selumetinib plus dacarbazine versus dacarbazine alone.

Uveal melanoma is commonly included in the exclusion criteria for studies of new therapies, making it difficult to find useful data to make treatment recommendations. The panel concluded that no specific recommendation could be made regarding patients with uveal melanoma and indicated that patients should be referred to clinical trials when possible.

Neoadjuvant Therapy

No specific recommendation could be made for or against neoadjuvant therapy for resectable cutaneous melanoma. Current evidence suggests that the best option for these patients is referral to a clinical trial.

In forming this conclusion, the expert panel reviewed 4 trials. Two small trials led by Rodabe N. Amaria, MD, were terminated early and failed to produce results sufficient for drawing a conclusion regarding efficacy. The first trial (NCT02231775), which looked at neoadjuvant and adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib versus contemporary standard of care in 21 patients, was stopped early due to significant event-free survival improvement in the experimental arm (HR, 0.016; 95% CI, 0.00012-0.1; P <.0001). The second trial (NCT02519322) consisted of 23 patients treated with neoadjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab versus single-agent nivolumab, both followed by adjuvant nivolumab. This trial was stopped early because patients had high toxicity rates and early disease progression.

Two other trials of different combinations of nivolumab and ipilimumab as neoadjuvant therapy failed to demonstrate a clear benefit at dose levels that did not lead to a significant increase in toxicity.

The panel concluded that potential benefit with neoadjuvant therapy may exist, and clinical trials are the best option for these patients.

“There are many studies open,” Seth said. “I think studies looking at the BRAF[/MEK] combinations and immunotherapy will be the ones to help us in the future.”

When asked about his current treatment preferences, Seth said, “in the time of COVID-19 [coronavirus disease 2019], I am using immunotherapies for patients [who] are unable to get surgery.

“I truly believe melanoma will become a treatable [disease],” Seth concluded. “The next 5 years are unknown, but we are bound to be better and more efficient in treatment.”

References:

1. Seth R, Messersmith H, Kaur V, et al. Systemic therapy for melanoma: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. Published online March 31, 2020. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.00198

2. Pasquali S, Hadjinicolaou AV, Chiarion Sileni V, Rossi CR, Mocellin S. Systemic treatments for metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2(2):CD011123. doi:10.1002/14651858. CD011123.pub2

3. FDA approves pembrolizumab for adjuvant treatment of melanoma. FDA. Updated March 18, 2019. Accessed May 22, 2020. bit.ly/3btFOiG

Survivorship Care Promotes Evidence-Based Approaches for Quality of Life and Beyond

March 21st 2025Frank J. Penedo, PhD, explains the challenges of survivorship care for patients with cancer and how he implements programs to support patients’ emotional, physical, and practical needs.

Read More