Assessing Risk for Optimal Treatment of High-Risk Polycythemia Vera in the Frontline Setting

During the NCCN 2022 Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies, Aaron Gerds, MD, explained risk stratification in patients with polycythemia vera, frontline treatment options, and outcomes for the patient population based on findings from clinical trials.

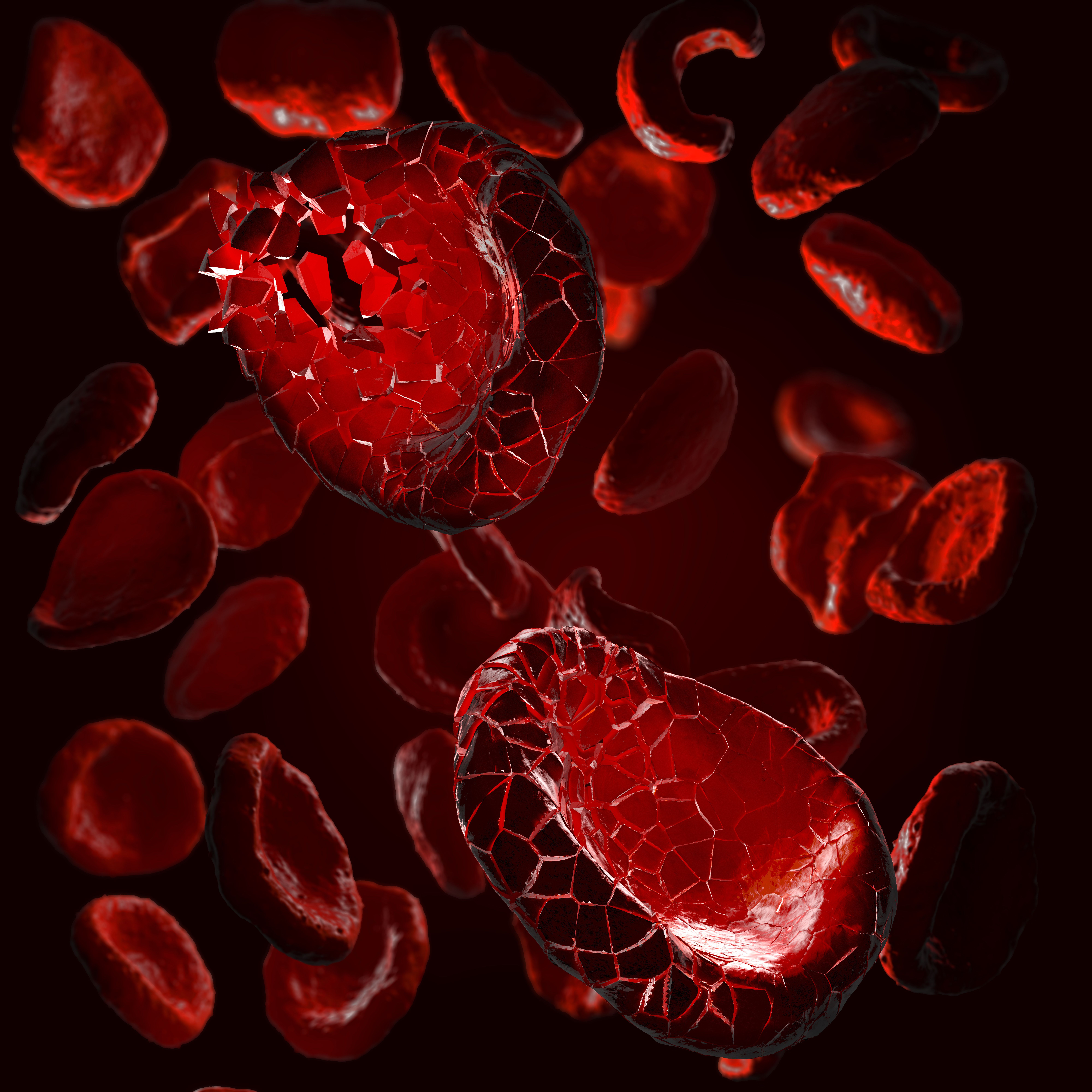

Several prognostic variables are important to help stratify risk in patients with polycythemia vera (PV). Patients’ risk is a determining factor for treatment with either chemotherapy, an interferon, or a JAK inhibitor.1

During the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2022 Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies, Aaron Gerds, MD, assistant professor in Medicine (Hematology and Medical Oncology) at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, explained risk stratification in patients with PV, frontline treatment options, and outcomes for the patient population based on findings from clinical trials including, PROUD-PV (NCT01949805), and CONTINUATION-PV (NCT02218047).

The key factors that determine whether a patient has high-risk PV are thrombosis history, leukocyte count, age (< 67 years), and the presence of adverse mutations like SRSF2.

“When we think about applying therapy for polycythemia vera, we really focused on the major complication of the disease, which is thrombosis, and to identify those who may be at higher risk of thrombosis we use age as well as our thrombosis history. If they have each of either those 2 markers, patients aren't considered to be high-risk, and the recommendation is to use some sort of cytoreductive therapy in addition to either phlebotomy or not, as well as cardiovascular risk factor modification, and daily aspirin,” Gerds explained.

Gerds also explained that multiple prospective and retrospective analyses hint that risk of thrombosis is linked with leukocytosis in patients with PV. He noted that although looking at white blood cell count is a different way to assess risk in patients with PV, it can help with treatment consideration, specifically for low-risk patients. For high-risk disease, a more targeted approach is needed, according to Gerds.

Treating High-Risk PV in the Frontline

Combined results from the PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV trials show high and durable hematological and molecular responses in patients with PV treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b (Besremi)vs hydroxyurea. The interferon treatment also demonstrated a tolerable safety profile in the phase 3 trial and extension study.1,2

Both the PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV phase 3, randomized, controlled, open-label studies were conducted in 48 study sites across Europe. In PROUD-PV, adult patients with PV were randomized 1:1 to receive ropeginterferon alfa-2b at a twice-weekly subcutaneous dose starting at 100 μg or oral hydroxyurea starting at 500 mg/day. The primary end point of the study was complete hematological response with normal spleen size at 12 months.2

Following 1 year of treatment in PROUD-PV, patients could enter CONTINUATION-PV, which was an extension trial. The coprimary end points explored in CONTINUATION-PV were complete hematological response with normalization of spleen size and with improved disease burden, complete hematological response with normalization of spleen size, and with improved disease burden.

Out of the 127 patients in the PROUD-PV trial, achievement of a complete hematological response with normal spleen size was observed in 21% of patients in the interferon arm vs 28% in the standard therapy arm. Out of the 257 patients who were randomly assigned in the study, 171 rolled over to the extension study. At a median follow-up of 182.1 weeks (IQR 166.3-201.7) in the interferon arm and 164.5 weeks (144.4-169.3) in the standard therapy arm, the complete hematological response with improved disease burden was observed in 53% of patient in the interferon arm vs 38% in the standard therapy arm.

“Something that we see somewhat routinely with interferons as compared to hydroxyurea and other therapies is lowering of the allele burden. When we check for the JAK2 mutation, we often get out allele fraction, which is the ratio of mutated to not mutated alleles being read on the PCR test. We can see in patients treated with interferons, the allele burden going down,” said Gerds about the results1. “Roughly 10% of patients treated with interferons will have a molecular remission, meaning that when we check for the JAK2 mutation, we don't detect it anymore, indicating maybe a deeper benefit for interferons over hydroxyurea in patients with polycythemia vera,” he added.

The most commonly occurring grade 3 and grade 4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in each study were increased γ-glutamyltransferase (6%), and increased alanine aminotransferase (3%) in patients treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b. In the standard therapy arm, the most frequent grade 3/4 TRAEs were leucopenia (5%), and thrombocytopenia (4%).2

During his presentation, Gerds also provided advice on when to move beyond interferons and hydroxyurea. In patients with PV who have had an inadequate response to treatment for 3 months or more, developed cytopenia at the lowest dose of cytoreductive therapy, or experience unacceptable toxicity at any dose of treatment, hematologists/oncologists should move on to a JAK inhibitor. In the second-line setting of PV, the approved JAK inhibitor is ruxolitinib (Jakafi), Gerds explained.1

REFERENCES:

1. Gerds, Aaron. Management of polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Lecture presented at NCCN 2022 Annual congress: Hematologic Malignancies; October 14-15, 2022; New York City, NY.

2. Gisslinger H, Klade C, Georgiev P, et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus standard therapy for polycythaemia vera (PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV): a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial and its extension study [published correction appears in Lancet Haematol. 2020 Feb 25;:]. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(3):e196-e208. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30236-4