Agarwal Considers Patient Eligibility Among Novel Antiandrogen Therapies in Nonmetastatic CRPC Setting

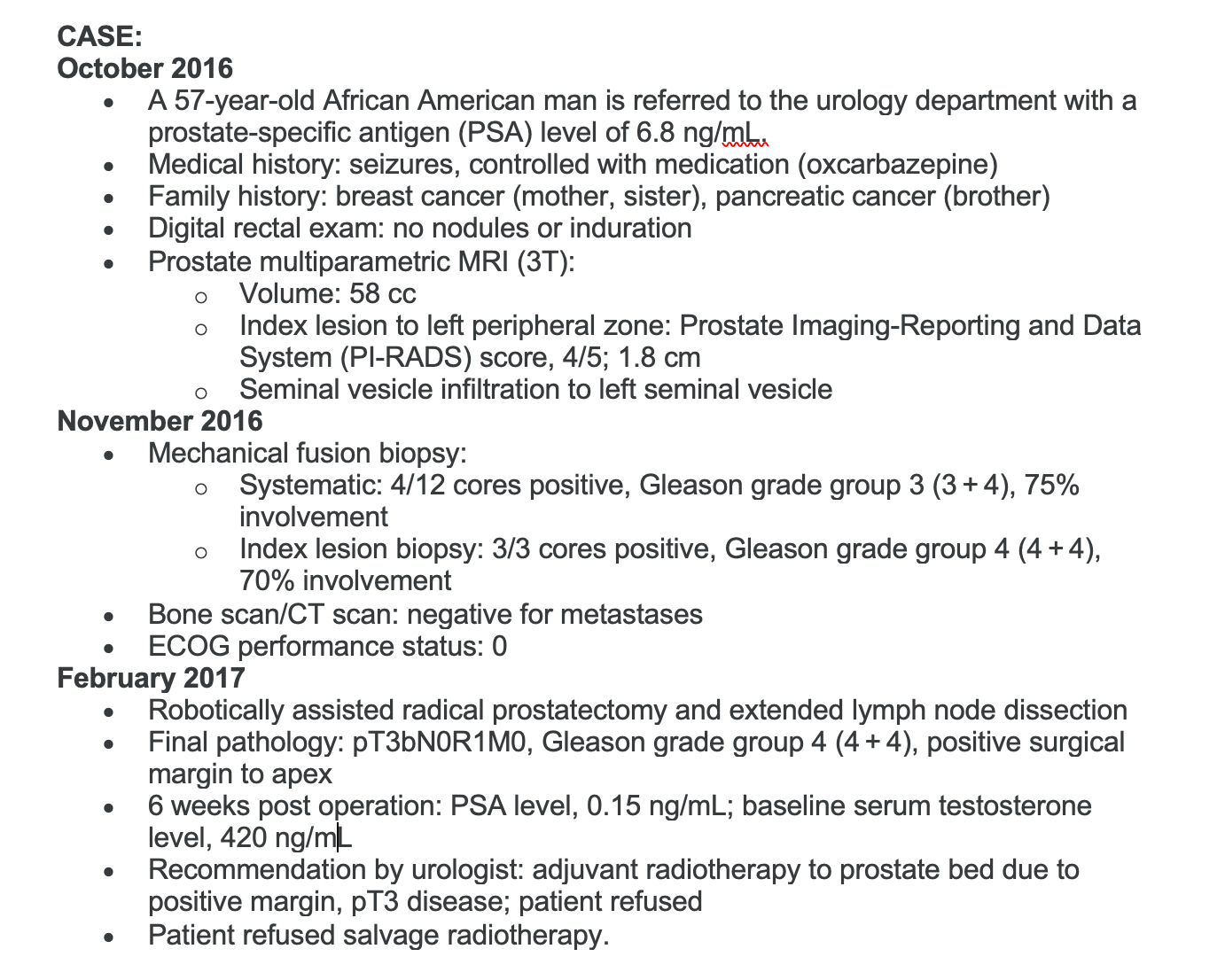

During a Targeted Oncology Case Based Peer Perspectives event, Neeraj Agarwal, MD, discussed the case of a 57-year-old male patient with nonmetastatic castration resistant prostate cancer.

Neeraj Agarwal, M

During a Targeted Oncology Case Based Peer Perspectives event, Neeraj Agarwal, MD, professor of Medicine, Presidential Endowed Chair of Cancer Research, director, Genitourinary Oncology Program, director, Center of Investigational Therapeutics, co-Leader, Experimental Therapeutic Program at Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah in Salt Lake City, UT, discussed the case of a 57-year-old male patient with nonmetastatic castration resistant prostate cancer.

Targeted OncologyTM: Is there a role for germline testing in this patient who has a sister and mother with breast cancer and a brother with pancreatic cancer?

Agarwal: Personally, I think this is a pretty slam dunk case. The answer is yes. We send these patients to a high-risk genetics clinic.

Would you suggest doing a fluciclovine (Axumin) or prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) PET scan?

In this case, I personally would have done a PSMA or Axumin scan to see if there [was] any local site of disease which can be radiated. My radiation oncology colleagues are very supportive of this approach. But in this case, let’s assume that all these scans were either not done or they were negative.

Is there a role for germline testing in this patient who has a sister and mother with breast cancer and a brother with pancreatic cancer?

Agarwal: Personally, I think this is a pretty slam dunk case. The answer is yes. We send these patients to a high-risk genetics clinic.

Would you suggest doing a fluciclovine (Axumin) or prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) PET scan?

In this case, I personally would have done a PSMA or Axumin scan to see if there [was] any local site of disease which can be radiated. My radiation oncology colleagues are very supportive of this approach. But in this case, let’s assume that all these scans were either not done or they were negative.

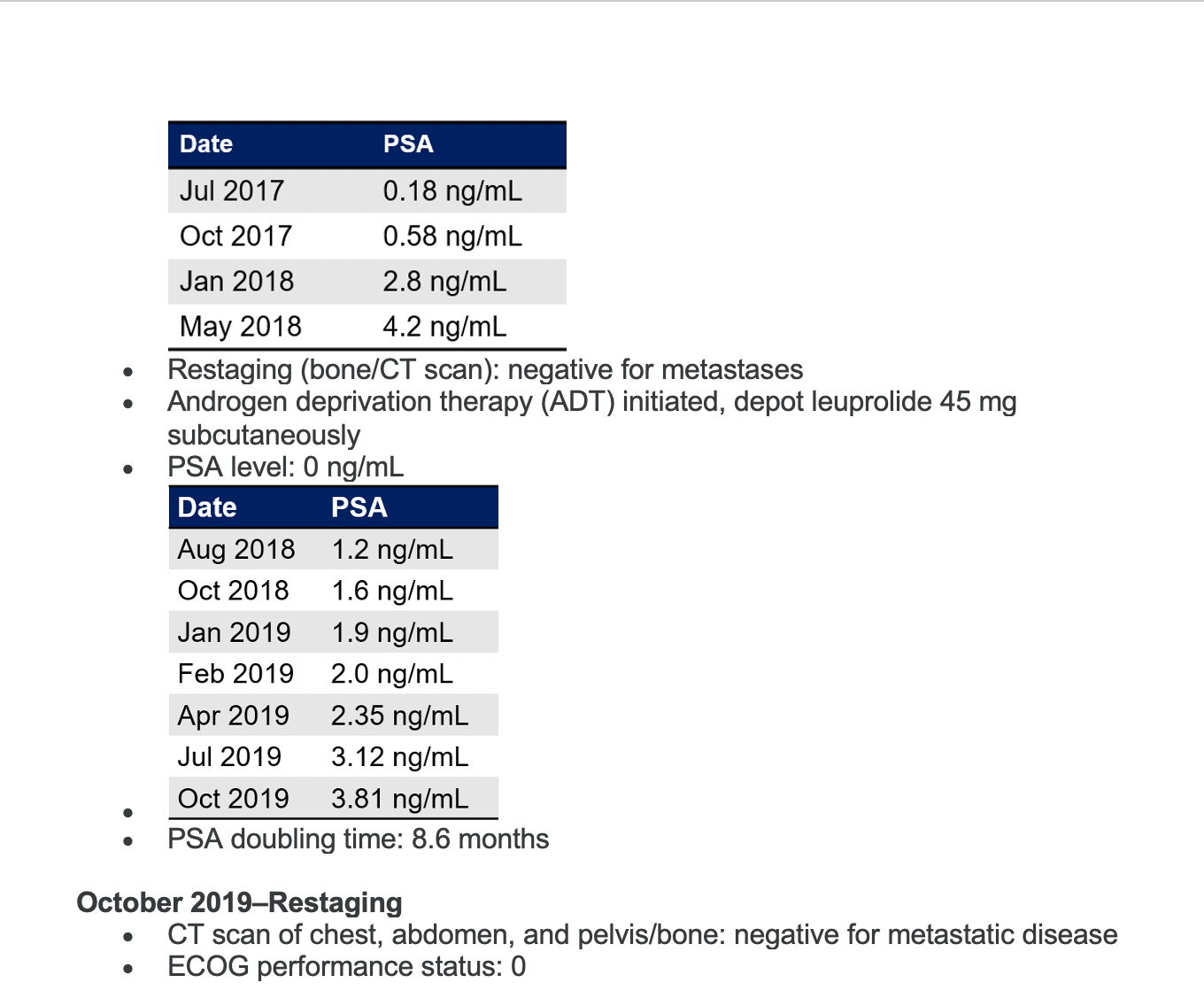

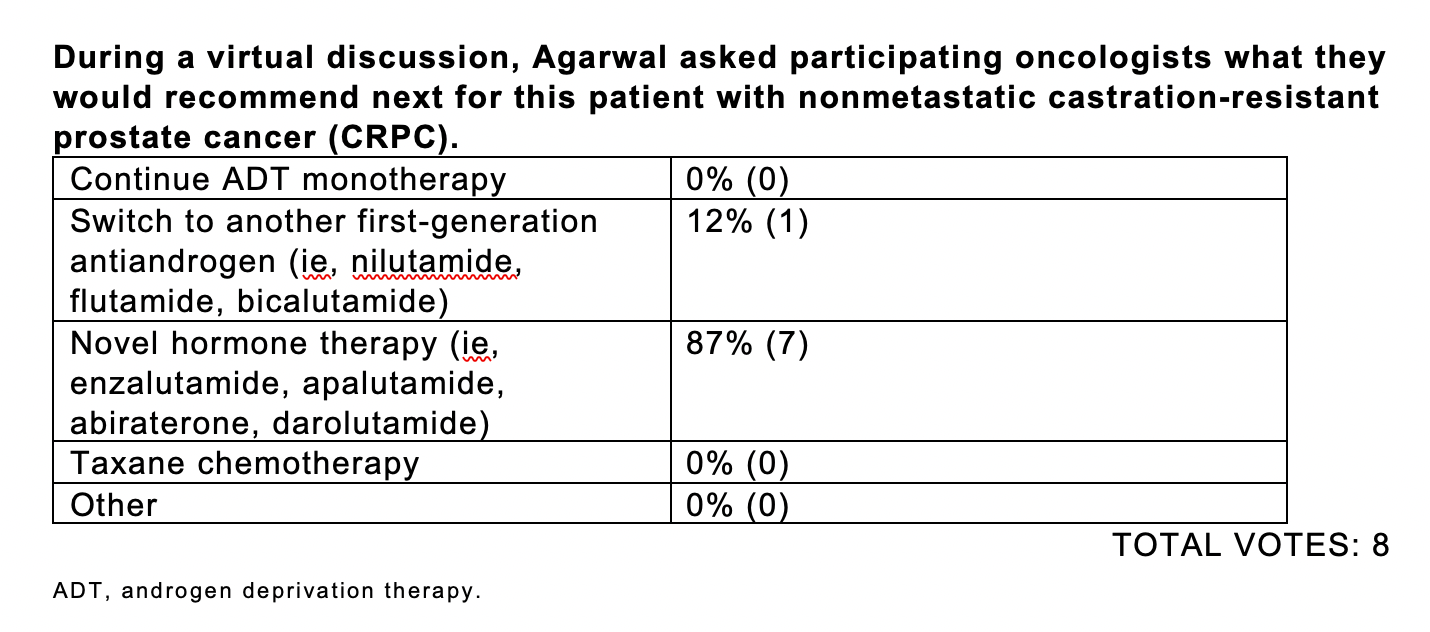

PSA is rising in this patient. Would you continue ADT as a monotherapy?

Yes, I would continue, but the question is would you just continue as monotherapy [or do something else]?

Most [responders] said they’d go for a novel hormonal therapy. Somebody said second-generation antiandrogen, which I think is a very reasonable answer.

I think, because PSA’s doubling time is 9 months, it qualifies [for] the eligibility criteria of all these drugs—[with a] PSA doubling time of 10 months or less. But really, what is the real PSA doubling time of the patients who went on the trial? That would be interesting to see. It’s hard to remember what the PSA doubling time of those patients actually was, even though you may have read the New England Journal of Medicine article today.

What are the treatment options available to this patient in terms of antiandrogens to add to ADT?

Enzalutamide [Xtandi] has the highest rate of central nervous system [CNS] penetration among these agents. Apalutamide [Erleada] has less CNS penetration.I think darolutamide [Nubeqa] is best from that perspective. That also translates [into fewer] CNS [adverse] effects with darolutamide, in my view. Does it affect the efficacy of darolutamide? I do not know. There has not been a head-to-head comparison of these agents. But it was given out up front that patients had seizures. So, enzalutamide and apalutamide are out [for this patient], in my view.

Again, there is no real contraindication. Yes, a patient had seizures, but sometimes seizure history is not that confirmatory. This patient was on a medication for seizures, so I would avoid enzalutamide in this case.

Abiraterone [Zytiga] is…not really a category 1 indication, and I would hesitate about using steroids for so long in a young man. So I think darolutamide would be my choice.

What are the recommendations for therapy with these agents?

The updated [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines on the use of these drugs [show] category 1 indications, because they are [supported by] large phase 3 trials showing overall survival [OS] improvement, which is considered the gold standard for prostate cancer patients.1 The PSA doubling time of more than 10 months—that’s the challenging area.

What is the role of bicalutamide and other first-generation antiandrogens in nonmetastatic CRPC?

I [can] tell you that I [have] used bicalutamide in nonmetastatic CRPC in those patients who have a PSA doubling time of more than 10 months. I think using bicalutamide in this setting is absolutely fine.

These patients eventually start progressing. PSA doubling time usually keeps going down and keeps becoming more rapid. But, I think bicalutamide does have a role in these patients.

What data support the use of these novel antiandrogens in this setting?

The trial designs are very familiar, and very similar, actually. Large trials started almost at the same time with apalutamide, enzalutamide, and darolutamide.

Looking at the SPARTAN trial [NCT01946204] first,2 [there were] 1200 patients with nonmetastatic CRPC, and [patients with] pelvic lymph nodes were included if [these] were less than 2 cm in size below iliac bifurcation. I don’t know how relevant it is, but I need to say that because [these lymph nodes were] a major eligibility criterion, which is different from our many other trials here. PSA doubling time was less than 10 months. Patients were randomized to apalutamide plus continuation of ADT versus placebo plus ADT. Metastasis-free survival [MFS] was the primary end point.

[These were] the baseline characteristics of the patients. 74 years was the median age. The real PSA doubling time on the trial was 4.4 months on the apalutamide arm and 4.5 months on the placebo arm. It basically tells me that even [in the case of] the treating clinicians, like me, who had this trial open in their sites, most of these patients did not get put on the trial for a PSA doubling time of 9 months or 10 months, which was [part of] the eligibility criteria. They really had a fast PSA doubling time in reality. If you look at further subgroups, [there was a] PSA doubling time of less than 6 months; 70% of patients had a PSA doubling time of less than 6 months. So, again, we can see what kind of population it was.

MFS was obviously very remarkably positive [40.5 months vs 16.2 months with placebo], with a hazard ratio [HR] of 0.28. Time to symptomatic progression was also remarkable, favoring apalutamide [HR, 0.45].

OS was recently reported [at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting].3 Again, it supported apalutamide over placebo. [It’s] not surprising, actually, but [consider] the magnitude of OS [73.9 months vs 59.9 months with placebo; HR, 0.78; P= .0161]. Until I saw this, I was not prescribing apalutamide in my clinic for [patients with] nonmetastatic prostate cancer. But when I saw this 14- or 15-month survival benefit, that really changed my mind.

The most frequent [adverse] effects––all I care [about]…[is] the most common one and the most striking one that affects my patient’s quality of life––fatigue and falls. Fall is important. It’s the reflection of fatigue, in my view. If you look at all-grade fatigue, 33% of patients on the apalutamide arm and 21% of patients on the placebo arm [experienced it]. If you look at grade 3 and 4 fatigue, [there was] not much; 0.9% [with apalutamide] and 0.3% with placebo plus ADT. Then falls; if you look at the falls, grade 3 and 4, [the incidence was 2.7% with apalutamide and 0.8% with] placebo plus ADT. I’m not sure how it is laid down here, but fatigue was higher with apalutamide, not that much higher, but still higher.

Skin rash, we’re looking for the skin rash. It’s not there. It means it was very uncommon. An [issue I get asked about often], especially in the context of metastatic CRPC, is skin rash. It looks like it was not very common, [occurring in less than 15% of patients]. In the TITAN trial [NCT02489318], it was 6% all rash, and grade 3 and 4 [events] were even lower.4

The PROSPER trial [NCT02003924] with enzalutamide [was a] very similar trial design. Patients had to have a PSA doubling time of 10 months or less. [Patients received] enzalutamide versus placebo. The primary end point was MFS, and OS was a secondary end point.5

The median age was strikingly similar to that in the SPARTAN trial—74 years. PSA doubling time [was] what investigators were [considering] before enrolling these patients in the trial—3.8 months vs 3.6 months. So it looks like they were rapidly progressing. The majority of patients [77%] had a PSA doubling time of less than 6 months.

MFS [was] 22 months longer with enzalutamide versus placebo [36.6 vs 14.7 months; HR, 0.29; P< .0001]. Median OS was also higher with enzalutamide versus placebo [67.0 vs 56.3 months]. The HR of 0.73 [was] very similar to what we saw with the SPARTAN trial.

Looking at the [adverse] effects now, I think it would be ideal to just compile all [of them] in 1 table, but that [would] be…with a big caveat of cross-trial comparisons. But looking at the fatigue part, 3% versus 1% grade 3 and above adverse events [occurred] in more than 1% of patients receiving enzalutamide. So, fatigue was 3 times higher with enzalutamide; grade 3 fatigue, 3% and 1%. I personally think [enzalutamide is] reasonable in my clinic. I won’t [be dissuaded] much by these differences. Falls were similar, 1% and 1%, and hypertension was 5% versus 2%.

Are any of you concerned about the cardiovascular adverse effects with enzalutamide?

I know when Dr Maha Hussain presented the data, there were a lot of questions about cardiovascular [adverse] effects, but it doesn’t look [as though] they are that different in each of the arms.

What data support the use of the agent that was chosen for this patient?

[Results from]the ARAMIS trial [NCT02200614, were recently] published in the New England Journal of Medicine.6,7 [1500] patients with high-risk nonmetastatic CRPC…were randomized to darolutamide versus placebo. Again, [this trial had a] very similar primary end point [to the others], MFS.

It looks like these trials were [almost] copying each other, not only in design but [in terms of the] type of patients that are included…—74 years as a median age. If you look at the PSA doubling time, [it was] 4.4 months or 4.7 months in the placebo arm. Again, the investigators mostly approved those patients on these trials, but they really thought disease was aggressively progressing. And again, 70%, more than two-thirds of patients, had a PSA doubling time of less than 6 months. Otherwise, they were very similar.

[This trial had an] MFS of [40.4 vs 18.4 months]—an 18-month difference, and a 59% risk reduction, with an HR of 0.41, which is remarkable, and consistent with other drugs, other novel agents.

In terms of prespecified and secondary exploratory end points, OS is clearly improved, with an HR of 0.71. Time to pain progression, time to cytotoxic chemotherapy, as expected, …are all better with darolutamide. Time to pain progression [40.3 vs 25.4 months; HR, 0.65] clearly improved, because we are delaying metastatic disease.

OS, [with an] HR of 0.71 [and a] 30% reduction in risk of death, is again very consistent with other novel agents.

I would say [the adverse event profile is] different from apalutamide and enzalutamide, with fatigue, tiredness, and falls. I think this is what is differentiating darolutamide from other drugs, fatigue and falls. Somehow, rash [occurs] more than with placebo [2.9% vs 0.9%], which is intriguing. I always identify rash with apalutamide or associate apalutamide with the rash. But darolutamide seems [to have] 3 times more rash compared with placebo.

Overall, how do you compare these novel agents?

[There is] very consistent improvement in MFS with all these agents, with an HR for MFS of 0.28 with apalutamide, 0.29 with enzalutamide, and 0.41 with darolutamide. [Regarding] OS, again [we see an] HR of 0.78 with apalutamide, 0.73 with enzalutamide, and 0.69 with darolutamide. So, [there is a] consistent reduction in risk of progression and death in the range of 30% to 40%.8

Does PSA doubling time affect your choice of therapy?

As we [discussed], in all those trials [it was] pretty much…very consistent that if you look at the patients who were actually recruited on…all 3 trials, SPARTAN, PROSPER, and ARAMIS, …the PSA doubling time was strikingly very similar, around 4 months. So, by the time the PSA doubling time is 4 months, we [tend] to think this is already a disease that is not curable with radiation or surgery.

How do you decide which of these agents to give in the nonmetastatic CRPC setting?

I’m more likely to prescribe one drug over another drug because of drug interactions. Darolutamide has [fewer] drug interactions. I personally have prescribed more enzalutamide for nonmetastatic CRPC, because that was the drug that was in my clinic for the last 6 years. So I didn’t have to change anything. I do have a template on Epic. My nurses are very familiar with enzalutamide, and apalutamide from last year. But I get stuck with drug interactions sometimes, [such as] anticoagulants. [For example,] patients are on…some antiarrhythmic drugs, then …a pharmacist tells me, ‘You cannot prescribe this drug, because it interacts.’ Then I start scratching my head, and I start looking for…the other option. I think, personally, darolutamide has [fewer] drug interactions. That is the most attractive part for me. If I prescribe darolutamide, that is the most common reason for me to do that…because no other drug can be prescribed for that given patient.

Multiple drug interactions [exist] with pretty much all these medications. But somehow, I have learned [about many of them] over the last 10 years of…seeing patients with prostate cancer, and darolutamide has been around for almost 3 years now in different forms, different trials and different forms, basically. Personally, I think it has the least amount of drug interactions. I still go with other medications. Sometimes I have no choice. It is the insurance choice, which I have to follow. If you have not seen a lot of [patients with] nonmetastatic prostate cancer, you will realize that it doesn’t matter what we prefer. I think it’s sometimes easier to go with the formulary of the insurance company.

Having said that, if somebody is having a drug interaction with, say, apalutamide, and there won’t be any drug interactions with darolutamide, it is very easy to have insurance change the drug to darolutamide, and vice versa. So, if you have a patient who has an interaction with darolutamide, but no interaction with enzalutamide, simply ask insurance; I think they’ll change it. That’s what my experience is.

References

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Prostate cancer, version 2.2020. Accessed August 17, 2020. https://bit.ly/32pmz7H

2. Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al; SPARTAN Investigators. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1408-1418. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1715546

3. Small EJ, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al. Final survival results from SPARTAN, a phase III study of apalutamide (APA) versus placebo (PBO) in patients (pts) with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(suppl 15):5516. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.5516

4. Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al; TITAN Investigators. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(1):13-24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1903307

5. Sternberg CN, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al; PROSPER Investigators. Enzalutamide and survival in nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2197-2206. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2003892

6. Fizazi K, Shore N, Tammela TL, et al; ARAMIS Investigators. Darolutamide in nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(13):1235-1246. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1815671

7. Fizazi K, Shore N, Tammela TL, et al; ARAMIS Investigators. Nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer and survival with darolutamide. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1040-1049. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001342

8. Gupta R, Sheng IY, Barata PC, Garcia JA. Non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: current status and future directions. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2020;20(6):513-522. doi:10.1080/14737140.2020.177275